Ancient genomes reveal where migrants arrived from and when they adapted to high altitudes.

Dyani Lewis

NEWS

17 March 2023

Modern Tibetan people are the descendants of people who have continually lived on the Tibetan Plateau for at least 5,000 years.

Modern inhabitants of the Tibetan Plateau are descendants of people who have occupied the ‘roof of the world’ for the past five millennia. In the biggest study of its kind, researchers sequenced dozens of ancient genomes from the region, revealing where its ancient settlers came from and how they adapted to high-altitude living1.

The Tibetan Plateau extends from the northern edge of the Himalayas across 2.5 million square kilometres. It is a high-altitude, dry and cold region. Despite its inhospitable environment, humans have been present on the plateau since prehistoric times. Denisovans, extinct hominins that interbred with both Neanderthals and the ancestors of modern humans, lived on the northeastern edge of the plateau 160,000 years ago. Stone tools made 30,000–40,000 years ago are further signs of an early human presence in the region2.

But when people established a permanent presence on the plateau — and where they came from — has been a matter of debate, says Qiaomei Fu, an evolutionary geneticist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, who led the study.

Historical records date back only 2,500 years. Dating of sediments with human hand- and footprints in the central plateau indicated that people might have lived there permanently as long as 7,400 years ago3.

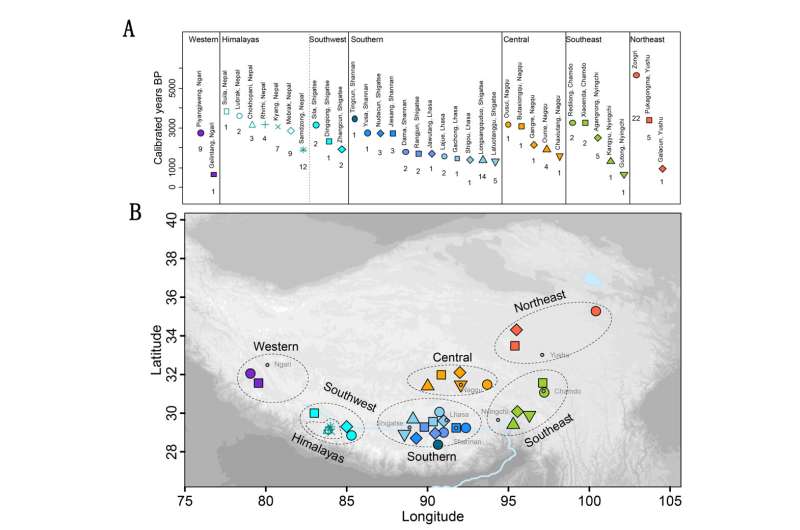

Fu and her team sequenced ancient genomes from the remains of 89 individuals, dated to 5,100–100 years ago, unearthed from 29 archaeological sites. Their study confirms that permanent occupation of the region pre-dates historical records. It also paints a complex picture of where early Tibetans migrated from, and how their interactions in the region and with their lowland neighbours shaped their heritage.

“It’s very exciting that we are getting ancient DNA from this geographical region,” says Vagheesh Narasimhan, a computational genomics researcher at the University of Texas at Austin.

Eastern origins

Analysis of the genomes reveals that the ancient occupants of the Tibetan Plateau have strong genetic links to the Tibetan, Sherpa and Qiang ethnic groups that live on or near the plateau today. Comparisons of the oldest genomes with ancient and living people across Asia suggest that the ancestors of modern Tibetans arrived on the plateau from the east. By contrast, India and the rest of the Asian subcontinent were populated by immigrants from eastern Eurasia and central Asia4.

“They were definitely East Asian, and they were northern East Asian,” says Fu. The genomes reveal fresh influxes of genes that suggest lowland East Asian immigrants arrived on the plateau more than once. Trade with millet farmers from the upper Yellow River region of what is now northeastern China was probably responsible for interactions between existing Tibetan settlers and newcomers before 4,700 years ago. During the past 700 years, there has been a further influx of genes from the east.

“There’s a continuity,” says Irene Gallego Romero, a genomics researcher at the University of Melbourne in Australia, “but there is also consistent movement of influences in and out of the region.”

Evidence of these interactions has existed in the form of pottery and other artefacts, but this is the first definitive sign that populations were exchanging more than their culture and knowledge, says Fu.

Living the high life

The genomes also reveal how Tibetan settlers adapted to their environment. Many present-day inhabitants of the Tibetan Plateau have a version of a gene, EPAS1, that allows them to thrive in the lower-oxygen environment5. The high-altitude variant of EPAS1 is thought to have originated from Denisovans.

Fu and her team were able to track the increasing prevalence of the high-altitude EPAS1 variant over time. Whereas just over one-third of the studied individuals dated to before 2,500 years ago had the variant, nearly 60% of those dated to between 1,600 and 700 years ago had the gene. That’s still lower than the 86% incidence in present-day Tibetans, suggesting that there’s been rapid selection for this variant in recent prehistory. “It’s a poster child for natural selection in humans in recent times,” says Narasimhan.

It’s still unclear when the high-altitude EPAS1 variant first appeared. “It would be really interesting to know how far back that goes,” says Gallego Romero. Fu is keen to answer this question by sequencing genomes of older remains, if they are discovered on the plateau.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00742-6

References

Wang, H. et al. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd5582 (2023).

Article Google Scholar

Zhang, X. L. et al. Science 362, 1049–1051 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Meyer, M. C. et al. Science 355, 64–67 (2017).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Narasimhan, V. M. et al. Science 365, eaat7487 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Huerta-Sánchez, E. et al. Nature 512, 194–197 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Jobs

POST-DOC POSITIONS IN THE FIELD OF “Automated Miniaturized Chemistry” supervised by Prof. Alexander Dömling

Palacky University (PU)

Olomouc, Czech Republic

Ph.D. POSITIONS IN THE FIELD OF “Automated miniaturized chemistry” supervised by Prof. Alexander Dömling

Palacky University (PU)

Olomouc, Czech Republic

Czech Advanced Technology and Research Institute opens A SENIOR RESEARCHER POSITION IN THE FIELD OF “Automated miniaturized chemistry” supervised by Prof. Alexander Dömling

Palacky University (PU)

Olomouc, Czech Republic

Professor of Pharmacology

Bangor University

Bangor, United Kingdom

Related Articles

Biggest Denisovan fossil yet spills ancient human’s secrets

Biggest Denisovan fossil yet spills ancient human’s secrets Mum’s a Neanderthal, Dad’s a Denisovan: First discovery of an ancient-human hybrid

Mum’s a Neanderthal, Dad’s a Denisovan: First discovery of an ancient-human hybridGenomic study of ancient humans sheds light on human evolution on the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau, the highest and largest plateau above sea level, is one of the harshest environments settled by humans. It has a cold and arid environment and its elevation often surpasses 4000 meters above sea level (masl). The plateau covers a wide expanse of Asia—approximately 2.5 million square kilometers—and is home to over 7 million people, primarily belonging to the Tibetan and Sherpa ethnic groups.

However, our understanding of their origins and history on the plateau is patchy. Despite a rich archaeological context spanning the plateau, sampling of DNA from ancient humans has been limited to a thin slice of the southwestern plateau in the Himalayas.

Now, a study published in Science Advances led by Prof. Fu Qiaomei from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has filled this gap by sequencing the genomes of 89 ancient humans dating back to 5100 BP from 29 archaeological sites spanning the Tibetan Plateau.

The researchers found that ancient humans living across the plateau share a single origin, deriving from a northern East Asian population that admixed with a deeply diverged, yet unsampled, human population.

"This pattern is found in populations since 5100 years ago, prior to the arrival of domesticated crops on the plateau," said Prof. Fu. She noted that the introduction of northern East Asian ancestry to plateau populations occurred before barley and wheat was introduced and was not associated with migrating wheat/barley agriculturalists.

A deeper comparison across the plateau reveals distinct genetic patterns prior to 2500 BP, indicating that three very different Tibetan populations occupied the northeastern, southern/central, and southern/southwestern regions of the plateau, with previously sampled plateau populations belonging only to the latter group.

Different population dynamics can be observed in these three regions. Northeastern populations younger than 4700 BP show an influx of additional northern East Asian ancestry in lower elevation regions (~3000 masl) such as the Gonghe Basin. However, this influx is not observed in higher elevation populations (~4000 masl) dating to 2800 BP just 500 km away.

An extended network of humans also lived along the Yarlung Tsangpo River, with a shared ancestry found in southern/southwestern populations dating to 3400 BP, western populations from Ngari Prefecture dating to 2300 BP, and southeastern populations from Nyingchi Prefecture dating to 2000 BP. The extended impact of these populations shows the important role this river valley played in Tibetan history.

"Between these two groups, central populations prior to 2500 BP share ancestry that differed from those further north and south. However, sampling of central populations after 1600 BP show that they share a closer genetic relationship to southern/southwestern populations. These patterns capture a dynamism in human populations on the plateau," said Melinda Yang, assistant professor at the University of Richmond and a previous postdoc at IVPP.

"While ancient plateau populations show primarily East Asian ancestry, Central Asian influences can be found in some ancient plateau populations," said Wang Hongru, professor at the Agricultural Genomics Institute in Shenzhen and a previous postdoc at IVPP. "Western populations show partial Central Asian ancestry as early as 2300 BP, and an individual dating to 1500 BP from the southwestern plateau additionally shows ancestry associated with Central Asian populations."

Present-day Tibetans and Sherpas show heavy influence from lowland East Asian populations, with differing levels of gene flow correlating with longitude. This pattern is not observed across populations of older time transects, including those dating from 1200–800 BP, indicating that lowland East Asian gene flow was largely a product of very recent human migration.

Previous research has shown that present-day plateau populations possess high frequencies of an endothelial Pas domain protein 1 (EPAS1) variant that is adaptive for living at high altitudes and likely originated from a past admixture event with the archaic humans known as Denisovans.

"Humans from this study show archaic ancestry typical of lowland East Asians, but the oldest individual dating to 5100 BP is homozygous for the adaptive variant," said Prof. Fu. "Thus, the arrival of this variant occurred prior to 5100 BP in the ancestral population that contributed to all plateau populations."

Through their broad spatiotemporal survey of ancient human DNA from the Tibetan Plateau, Prof. Fu and her team have revealed a Tibetan lineage that dates back to at least 5100 years ago on the Tibetan Plateau. The ancestral population diversified rapidly, such that three regional groups show unique historical patterns that began to merge after 2500 BP.

"This is the largest study of ancient genetics on the Tibetan Plateau to date," said Lu Hongliang, a professor at Sichuan University. The new evidence in this study on the formation of unique components in the ancient populations from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is highly reliant on collaboration between multiple archaeological teams and geneticists. Prof. Lu notes that "Analyzing ancient DNA allows us to go beyond the study of cultural interaction using only archaeological evidence, and to put forward new ideas for archaeological research on the plateau."

Future sampling is still needed, as the origin of the unsampled, deeply diverged ancestry found in all plateau populations is still unaccounted for. In addition, when and where the adaptive EPAS1 allele first entered the ancestral Tibetan population is still unknown.

But this study is a step in the right direction. "These genomes reveal a deep and diversified history of humans on the plateau," said Prof. Fu. "With these findings, we have a much better understanding of an important part of human history in Asia."

More information: Hongru Wang et al, Human genetic history on the Tibetan Plateau in the last 5,100 years, Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.add5582. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.add5582

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by Chinese Academy of ScienceSouth Asian black carbon causes glacier loss on Tibetan Plateau

No comments:

Post a Comment