Ancient brain structure turns out to be more important than realized

by Eric W. Dolan

January 30, 2024

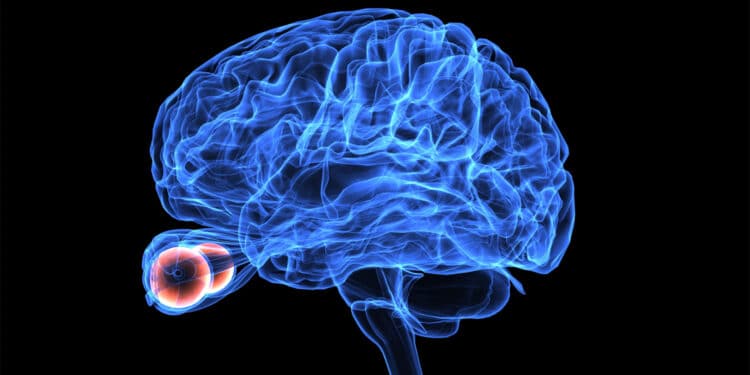

(Photo credit: Adobe Stock)

In a groundbreaking study by the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, researchers have unveiled that a small, often-overlooked part of the brain, known as the superior colliculus, plays a more vital role in how we see and perceive the world than previously understood. This discovery, centering on the brain’s ability to distinguish objects from their backgrounds, could reshape our understanding of vision and has potential implications for addressing visual impairments.

The new findings have been published in the journal eLife.

The motivation behind this study stems from a long-standing puzzle in neuroscience: how does the brain differentiate an object from its surroundings? While it’s known that the visual cortex, a part of the brain typically associated with processing visual information, plays a role in this, there are animals with less developed visual cortices that can still perform this task effectively. This observation led researchers to ponder whether another part of the brain could also be contributing to this ability, particularly the superior colliculus, an evolutionarily ancient structure present in all classes of vertebrates.

To investigate this, the researchers turned to mice due to their anatomical similarity to humans in having both a visual cortex and a superior colliculus. The study involved a series of experiments with 16 mice, where they were trained to recognize and respond to images depicting figures against various backgrounds. This task was designed to mimic the challenge of identifying objects in different visual contexts, similar to how animals in the wild might need to spot prey or predators.

The researchers employed a technique called optogenetics, which involves using light to control cells in living tissue. Specifically, they used this method to temporarily deactivate the superior colliculus in the mice. By comparing the mice’s performance in the visual tasks with and without the superior colliculus being active, the researchers could gauge the importance of this brain area in visual processing. Additionally, they used electrophysiology, a method of recording electrical activity in the brain, to observe how neurons in the superior colliculus responded during the tasks.

The findings were revelatory. When the superior colliculus was deactivated, the mice struggled significantly more in distinguishing the figures from the backgrounds, indicating that this part of the brain plays a critical role in object detection, especially in complex visual environments. Moreover, the researchers discovered that specific neurons in the superficial layers of the superior colliculus showed increased activity in response to the visual stimuli used in the tasks. This neural behavior correlated with the mice’s performance, suggesting that the superior colliculus contains a specialized neural code for detecting objects.

One of the study’s most intriguing aspects was the realization that the brain employs parallel pathways for visual processing. While the role of the visual cortex is well-established, this research highlights the superior colliculus as another key player in the visual system, operating potentially in tandem with the visual cortex.

In a news release, study author J. Alexander Heimel explained: “Previous research already showed that a mouse can still complete the task if you turn off its visual cortex, which suggests that there is a parallel pathway for visual object detection. In this study, we switched off the superior colliculus using optogenetics to see what effect that would have. Contrary to the previous study, the mice became worse at detecting the object, indicating that the superior colliculus plays an important role during this process. Our measurements also showed that information about the visual task is present in the superior colliculus, and that this information is less present the moment a mouse makes a mistake. So, its performance in the task correlates with what we’re measuring.”

However, the study is not without limitations. The focus was primarily on the superficial layers of the superior colliculus, leaving the role of its deeper layers somewhat unexplored. Moreover, the study was conducted on mice, and while they share similarities with humans in terms of brain structure, there are notable differences. In humans, for instance, the visual cortex is far more developed, suggesting that the superior colliculus might play a less prominent but still significant role in our vision.

Future research directions could involve exploring the deeper layers of the superior colliculus and investigating how it interacts with other parts of the brain during visual processing. Additionally, studies on humans, possibly using non-invasive imaging techniques, could provide further insights into the role of the superior colliculus in human vision and its potential implications for treating visual impairments.

“How this works in humans is not entirely clear yet,” Heimel said. “Although humans also have two parallel systems, their visual cortex is much more developed. The superior colliculus may therefore play a less important role in humans. It is known that the moment someone starts waving, the superior colliculus directs your gaze there. It is also striking that those who are blind with a double lesion in the visual cortex do not see anything consciously but can often still navigate and avoid objects. Our research shows that the superior colliculus might be responsible for this and may therefore be doing more than we thought.”

The study, “Involvement of superior colliculus in complex figure detection of mice“, was authored by J. Leonie Cazemier, Robin Haak, T.K. Loan Tran, Ann T.Y. Hsu, Medina Husic, Brandon D. Peri, Lisa Kirchberger, Matthew W. Self, Pieter Roelfsema, and J. Alexander Heimel.

No comments:

Post a Comment