Warnings were issued on World Press Freedom Day that media freedoms have declined, with governments being blamed for the deterioration.

To mark the day on Friday the pressure group Reporters Without Borders (RSF) published a global index detailing the working conditions for journalists in 180 countries.

Within the European Union it labels conditions for journalists as "problematic" in Greece, as well as in Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Ukraine and Poland.

In Serbia and Albania, conditions are labeled as "difficult," indicating a worse state. In Russia, Belarus, and Turkey, the situation is even more severe, categorised as "very serious."

According to the report, in Russia "more than 1,500 journalists have fled abroad since the invasion of Ukraine".

It also warns that, "press freedom is being put to the test by the ruling parties in Hungary (67th), Malta (73rd) and Greece (88th), the EU’s three worst-ranked countries. Giorgia Meloni’s Italy (46th) has also fallen five places".

But there have been some improvements in Europe. "The political environment for journalism has improved in Poland (up 10 to 47th) and Bulgaria (up 12 to 59th) thanks to new governments with more concern for the right to information".

Watchdog: Governments aren't doing enough to protect press freedom

By Liam Scott

Threats posed by governments and lawmakers are among the most concerning challenges for journalists around the world, Reporters Without Borders said in a report on Friday.

More governments and political authorities are failing to support and respect press freedom, the media watchdog, known as RSF, said as it released its annual World Press Freedom Index.

The rankings look at the political, legal, and economic factors affecting media, as well as the security situation for journalists in 180 countries and territories. Each is then assigned a score, where 1 shows the best environment.

The political sector saw the greatest deterioration of press freedom across all regions, RSF said.

“Political actors are more emboldened to denigrate the media, to vilify the press, to attack individual members of the press and journalists, to seek to weaponize the government apparatus against individual media outlets that are critical of them,” Clayton Weimers, the head of RSF’s U.S. office, told VOA.

That trend is all the more worrisome in a year where dozens of countries are set to hold national elections in 2024. Elections often feature violence against journalists and other curbs on press freedom, according to RSF.

Argentina experienced one of the biggest declines in media freedom compared to last year, Weimers said. It dropped from 40th place to 66th in the index.

The fall is due in large part to the election of President Javier Milei, “who has been openly hostile towards the media, has de-funded public media in Argentina and is leading the charge to vilify the press,” Weimers said.

Milei’s actions against the media underscores a broader phenomenon in which states and other political forces are playing a decreasing role in protecting press freedom, according to RSF.

Argentina’s Washington embassy did not immediately reply to VOA’s email requesting comment.

Norway maintained its status as the top country in the world for press freedom. Other countries in the top five include Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands and Finland.

At the bottom of the list are Iran, North Korea, Afghanistan, Syria and Eritrea.

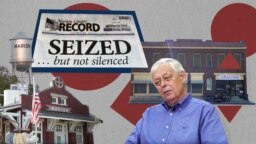

The United States dropped 10 spots to 55th as a result of journalist arrests and last year’s police raid on a newspaper in Kansas.

SEE ALSO:

Last of the Watchdogs

Emily Wilkins, the president of the National Press Club in Washington, said it’s concerning to see press freedom under threat in the U.S. She pointed to harmful rhetoric from politicians as one specific worry.

“Politicians position themselves as being anti the press, calling the press enemies of the people,” Wilkins told VOA. “Every time that they villainize reporters and the media as a whole, that is a knock against democracy, and that is something that is making our entire country weaker.”

Russia’s two-point rise to a rank of 162nd is misleading. RSF says its global press freedom score actually got worse — but other countries fell even more.

“To be honest, 2023 didn’t see a lot of changes because the situation got so bad in 2022 that it can't get much worse,” Weimers said about Russia.

Factors contributing to that decline are Russia’s jailing of journalists, including two Americans.

The Wall Street Journal’s Evan Gershkovich has been jailed since March 2023 on espionage charges that he, his employer and the U.S. government deny. The State Department has also declared the 32-year-old wrongfully detained.

Alsu Kurmasheva, an editor at VOA’s sister outlet Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, has been jailed since October 2023 on charges of failing to self-register as a so-called “foreign agent” and spreading what Moscow views as false information about the Russian military. She and her employer reject the charges.

Press freedom groups have criticized the State Department for not declaring Kurmasheva wrongfully detained. The designation would open up additional resources to help secure her release.

“It’s very critical that the State Department go forward and declare her wrongfully detained. I think a lot of us in the journalism community are very concerned that that hasn’t already happened,” Wilkins said.

State Department officials are still deciding whether to declare Kurmasheva wrongfully detained, Roger Carstens, the U.S. special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, told reporters in April.

“The Department of State continuously reviews the circumstances surrounding the detentions of U.S. nationals overseas, including those in Russia, for indicators that they are wrongful,” a State Department spokesperson previously told VOA.

China, which is the worst jailer of journalists in the world, remained at the bottom of the index at 172nd.

“We’re very concerned that China is setting itself up as an export model for anti-democratic values that clamp down on press freedom and freedom of speech,” Weimers said.

But it’s not all bad news.

Improvements in Ukraine, for instance, mean the country rose 18 places to 61st, and in South America, Chile rose 31 places to 52nd.

RSF ranks Turkey 158th in new press freedom index, underreports number of jailed journalists

Turkey was ranked 158th out of 180 countries in the 2024 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), while the organization reported the number of imprisoned journalists in the country at seven, far below what local and international rights groups report.

Turkey’s 2024 ranking on the RSF index is up from 165th last year; however, according to RSF the minor change for the better is not a result of the improvement of freedom of the press in the country but rather due to regression elsewhere.

Rights groups routinely accuse the Turkish government of trying to keep the press under control by imprisoning journalists, eliminating media outlets, overseeing the purchase of media brands by pro-government conglomerates and using regulatory authorities to exert financial pressure, especially since President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan survived a failed coup in July 2016.

Since the failed coup, when journalists were subjected to mass arrests on bogus coup or terrorism charges, local and international press organizations release varying figures for the number of journalists jailed in the country.

According to a census from the Expression Interrupted Platform, there are currently 32 journalists in prison in Turkey, mainly comprising Kurdish journalists and those who worked for media outlets affiliated with the Gülen movement.

The faith-based Gülen movement is accused by the Turkish government of masterminding a failed coup in July 2016 and is labelled as a terrorist organization. The movement, inspired by the views of Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen, strongly denies the accusations.

According to Turkey’s leading press union, the Journalists’ Union of Turkey (TGS), in the past year, 69 journalists were detained and 264 stood trial. Sixty-three were acquitted, while 36 verdicts against journalists resulted in a total of 55 years in prison.

Turkish Minute tried to contact RSF’s Turkey representative, Erol Önderoğlu, for a comment on the low number of imprisoned journalists reported by his organization, but was unable to reach him.

According to RSF, Erdoğan’s re-election in May of last year is a source of concern as the country continues to lose points in the index.

The index is calculated using a score from 0 to 100, where 100 represents the highest level of press freedom and 0 the lowest. This score is derived from both a quantitative tally of abuses against media and journalists and a qualitative analysis by press freedom experts, who respond to an RSF questionnaire available in 24 languages.

The questionnaire evaluates five key indicators: political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context and safety. These indicators provide a comprehensive view of the various challenges and threats journalists face.

The press freedom map visualizes these scores, categorizing countries into five groups based on their scores: good (green, 85-100 points), satisfactory (yellow, 70-85 points), problematic (light orange, 55-70 points), difficult (dark orange, 40-55 points) and very serious (dark red, 0-40 points).

Each country’s overall score is determined by subsidiary scores for each of the five contextual indicators, which are weighted equally. Within each indicator, all questions and subquestions also have equal weight.

Political context (33 questions and subquestions) examines the level of media autonomy, the acceptance of varied journalistic approaches and the support for media’s role in holding the government accountable.

Legal framework (25 questions and subquestions) assesses the freedom of journalists to work without censorship or judicial sanctions and the protection of journalists’ rights to access information and protect their sources.

Economic context (25 questions and subquestions) evaluates economic constraints imposed by government policies, non-state actors like advertisers and media owners who might use their platforms to promote personal business interests.

Sociocultural context (22 questions and subquestions) looks at social and cultural constraints that affect media coverage, including issues of gender, ethnicity and cultural pressures not to challenge powerful entities.

Safety (12 questions and subquestions) focuses on the physical and psychological safety of journalists, including risks of violence, harassment and professional harm.

The RSF index for 2024 ranks Turkey 158th out of 180 countries with an overall score of 31.6, which is a deterioration compared to the 2023 score (33.97), remaining in the “very serious” category.

The analysis for 2024 shows a significant decline in the political indicator, which falls from a score of 36.56 in 2023 to 20.02, putting Turkey in 165th place in this category.

The economic context remains relatively stable, changing slightly from 29.41 in 2023 to 28.91. The legal framework score has fallen from 41.16 to 37.38. In contrast, there are slight improvements in the sociocultural context and safety indicators, with the former rising from 30.11 to 37.05 and the latter from 32.58 to 34.63.

According to RSF, biased public broadcasting during the election period, the arrest of dozens of journalists and impunity are developments that make Turkey one of the countries regressing the most in terms of “political” factors affecting the media.

The investigations and prosecutions conducted against journalists on accusations of “disinformation” following earthquakes in February 2023 are signs that things are not going well in terms of the legal framework, according to the organization.

Turkey was accordingly among the countries in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) region that saw the most serious decline in the political context.

Turkey was ranked 158th out of 180 countries in the 2024 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), while the organization reported the number of imprisoned journalists in the country at seven, far below what local and international rights groups report.

Turkey’s 2024 ranking on the RSF index is up from 165th last year; however, according to RSF the minor change for the better is not a result of the improvement of freedom of the press in the country but rather due to regression elsewhere.

Rights groups routinely accuse the Turkish government of trying to keep the press under control by imprisoning journalists, eliminating media outlets, overseeing the purchase of media brands by pro-government conglomerates and using regulatory authorities to exert financial pressure, especially since President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan survived a failed coup in July 2016.

Since the failed coup, when journalists were subjected to mass arrests on bogus coup or terrorism charges, local and international press organizations release varying figures for the number of journalists jailed in the country.

According to a census from the Expression Interrupted Platform, there are currently 32 journalists in prison in Turkey, mainly comprising Kurdish journalists and those who worked for media outlets affiliated with the Gülen movement.

The faith-based Gülen movement is accused by the Turkish government of masterminding a failed coup in July 2016 and is labelled as a terrorist organization. The movement, inspired by the views of Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen, strongly denies the accusations.

According to Turkey’s leading press union, the Journalists’ Union of Turkey (TGS), in the past year, 69 journalists were detained and 264 stood trial. Sixty-three were acquitted, while 36 verdicts against journalists resulted in a total of 55 years in prison.

Turkish Minute tried to contact RSF’s Turkey representative, Erol Önderoğlu, for a comment on the low number of imprisoned journalists reported by his organization, but was unable to reach him.

According to RSF, Erdoğan’s re-election in May of last year is a source of concern as the country continues to lose points in the index.

The index is calculated using a score from 0 to 100, where 100 represents the highest level of press freedom and 0 the lowest. This score is derived from both a quantitative tally of abuses against media and journalists and a qualitative analysis by press freedom experts, who respond to an RSF questionnaire available in 24 languages.

The questionnaire evaluates five key indicators: political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context and safety. These indicators provide a comprehensive view of the various challenges and threats journalists face.

The press freedom map visualizes these scores, categorizing countries into five groups based on their scores: good (green, 85-100 points), satisfactory (yellow, 70-85 points), problematic (light orange, 55-70 points), difficult (dark orange, 40-55 points) and very serious (dark red, 0-40 points).

Each country’s overall score is determined by subsidiary scores for each of the five contextual indicators, which are weighted equally. Within each indicator, all questions and subquestions also have equal weight.

Political context (33 questions and subquestions) examines the level of media autonomy, the acceptance of varied journalistic approaches and the support for media’s role in holding the government accountable.

Legal framework (25 questions and subquestions) assesses the freedom of journalists to work without censorship or judicial sanctions and the protection of journalists’ rights to access information and protect their sources.

Economic context (25 questions and subquestions) evaluates economic constraints imposed by government policies, non-state actors like advertisers and media owners who might use their platforms to promote personal business interests.

Sociocultural context (22 questions and subquestions) looks at social and cultural constraints that affect media coverage, including issues of gender, ethnicity and cultural pressures not to challenge powerful entities.

Safety (12 questions and subquestions) focuses on the physical and psychological safety of journalists, including risks of violence, harassment and professional harm.

The RSF index for 2024 ranks Turkey 158th out of 180 countries with an overall score of 31.6, which is a deterioration compared to the 2023 score (33.97), remaining in the “very serious” category.

The analysis for 2024 shows a significant decline in the political indicator, which falls from a score of 36.56 in 2023 to 20.02, putting Turkey in 165th place in this category.

The economic context remains relatively stable, changing slightly from 29.41 in 2023 to 28.91. The legal framework score has fallen from 41.16 to 37.38. In contrast, there are slight improvements in the sociocultural context and safety indicators, with the former rising from 30.11 to 37.05 and the latter from 32.58 to 34.63.

According to RSF, biased public broadcasting during the election period, the arrest of dozens of journalists and impunity are developments that make Turkey one of the countries regressing the most in terms of “political” factors affecting the media.

The investigations and prosecutions conducted against journalists on accusations of “disinformation” following earthquakes in February 2023 are signs that things are not going well in terms of the legal framework, according to the organization.

Turkey was accordingly among the countries in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) region that saw the most serious decline in the political context.

No comments:

Post a Comment