Why governments and big oil cannot face the future

By Ann PettiforOctober 10, 2024

Source: Ann Pettifor's Substack

Themeisle - CopenHill Sky Slope Chimney Smoking. Flickr.

It wasn’t the shock of learning that £22 billion had emerged – out of thin air – from Labour’s supposedly austere Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves.

No, it was the time-span of the funding – a quarter of a century – and the confidence that future profits, jobs and skills can be protected for all that time. That shocked me.

That the world still has 25 years in which to prolong fossil capitalism, now assisted by carbon capture.

The Labour government in its manifesto promised to make “Britain a clean energy superpower” yet has agreed to invest £22 billion to ‘capture’ CO2 and extend the output, profits and dividends of global oil company shareholders – like Norwegian state-owned Equinor and Eni – for 25 years. A deal that by the way, has the support of the union of high paid oil rig workers. Their General Secretary Mike Clancy explained that:

Siting this new technology in areas where high carbon jobs are being phased out is also vital to support our industrial heartlands and ensure future jobs and skills. (Emphasis added).

I am reminded of the political ad in Adam McKay’s brilliant satire “Don’t Look Up”. An actress, cradling a hot drink in her cosy kitchen, channels Elon Musk and tells us she’s looking forward to

the jobs the comet will bring.

What this story reveals is stark: the future that matters to the new Labour government is that of the oil companies, not that facing younger generations. If I were younger (sigh) I would join other children that have filed suits – and challenge the Labour government’s decision to help energy companies prolong the extraction and exploitation of fossil fuels, and thereby threaten their futures.

The Technology

There will now be a heated debate on the unproven merits of carbon capture technology. The government aided by the industry will fight back, and the argument will be exhausting and will probably go nowhere. However, the debate is likely to detract us from the real issue. A Labour government’s delusion: that capitalism can address the crises associated with climate breakdown and the accelerating degradation of nature – our life support system.

I want to explain why that is a delusion. Why capitalism is a major cause of the ecological crises we face; and why the system and its ideology is unfit to tackle those crises.

It has all to do with capitalism’s mis-representation of Time – the theme of my last post: Capitalism, Asset Valuation and Time.

Whose future is it to be?

Themeisle - CopenHill Sky Slope Chimney Smoking. Flickr.

It wasn’t the shock of learning that £22 billion had emerged – out of thin air – from Labour’s supposedly austere Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves.

No, it was the time-span of the funding – a quarter of a century – and the confidence that future profits, jobs and skills can be protected for all that time. That shocked me.

That the world still has 25 years in which to prolong fossil capitalism, now assisted by carbon capture.

The Labour government in its manifesto promised to make “Britain a clean energy superpower” yet has agreed to invest £22 billion to ‘capture’ CO2 and extend the output, profits and dividends of global oil company shareholders – like Norwegian state-owned Equinor and Eni – for 25 years. A deal that by the way, has the support of the union of high paid oil rig workers. Their General Secretary Mike Clancy explained that:

Siting this new technology in areas where high carbon jobs are being phased out is also vital to support our industrial heartlands and ensure future jobs and skills. (Emphasis added).

I am reminded of the political ad in Adam McKay’s brilliant satire “Don’t Look Up”. An actress, cradling a hot drink in her cosy kitchen, channels Elon Musk and tells us she’s looking forward to

the jobs the comet will bring.

What this story reveals is stark: the future that matters to the new Labour government is that of the oil companies, not that facing younger generations. If I were younger (sigh) I would join other children that have filed suits – and challenge the Labour government’s decision to help energy companies prolong the extraction and exploitation of fossil fuels, and thereby threaten their futures.

The Technology

There will now be a heated debate on the unproven merits of carbon capture technology. The government aided by the industry will fight back, and the argument will be exhausting and will probably go nowhere. However, the debate is likely to detract us from the real issue. A Labour government’s delusion: that capitalism can address the crises associated with climate breakdown and the accelerating degradation of nature – our life support system.

I want to explain why that is a delusion. Why capitalism is a major cause of the ecological crises we face; and why the system and its ideology is unfit to tackle those crises.

It has all to do with capitalism’s mis-representation of Time – the theme of my last post: Capitalism, Asset Valuation and Time.

Whose future is it to be?

Readers will recall the section in the last post on the ‘nerve-wracking’ valuation of assets as determined in the present, but that the real value of an asset or collateral “

is calculated on the basis of the yet-to-be-actualised future income streams.

Much of capitalism’s preoccupation with the future was theorised by Irving Fisher, a prominent American economist in the early 20th century. He argued that capitalism was in a specific relationships to time – as Liliana Doganova explains, and is

resolutely future-oriented, in which any entity could engage and hence become capital.

The Orchard and the Future

Fisher used the apple tree as an example. The orchard that produces apples (i.e. will generate apples in the future) represents capital. But it is the value of the apples, not the tree or land the orchard rests on, that produces capitalism’s real value.

As value depends only on future capital gains, not the present nor the past, the value of the land can be discounted. If apples can’t be profitably sold in the future, then the orchard becomes redundant. Its ancient trees should be ripped up and the land turned over to a ‘productive’ crop more likely to ensure capital gains in the future.

That formula explains so much about capitalism’s destruction of nature.

Fisher’s theory led to a method widely used by firms making investment decisions. The value (Net Present Value (NPV) of any investment is calculated by projecting the flows of future costs and benefits. The inherent contradiction in the theory is that flows are then ‘discounted’ by e.g. a rate of interest, to determine the present value of a future sum of money, and based on the assumption that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow.

While value therefore depends only on the future, at the same time the future is devalued as a time less worthy than the present – because time has a cost.

Rockhopper, the Adriatic Coast, and Discounted Cash Flow Analysis (DCF)

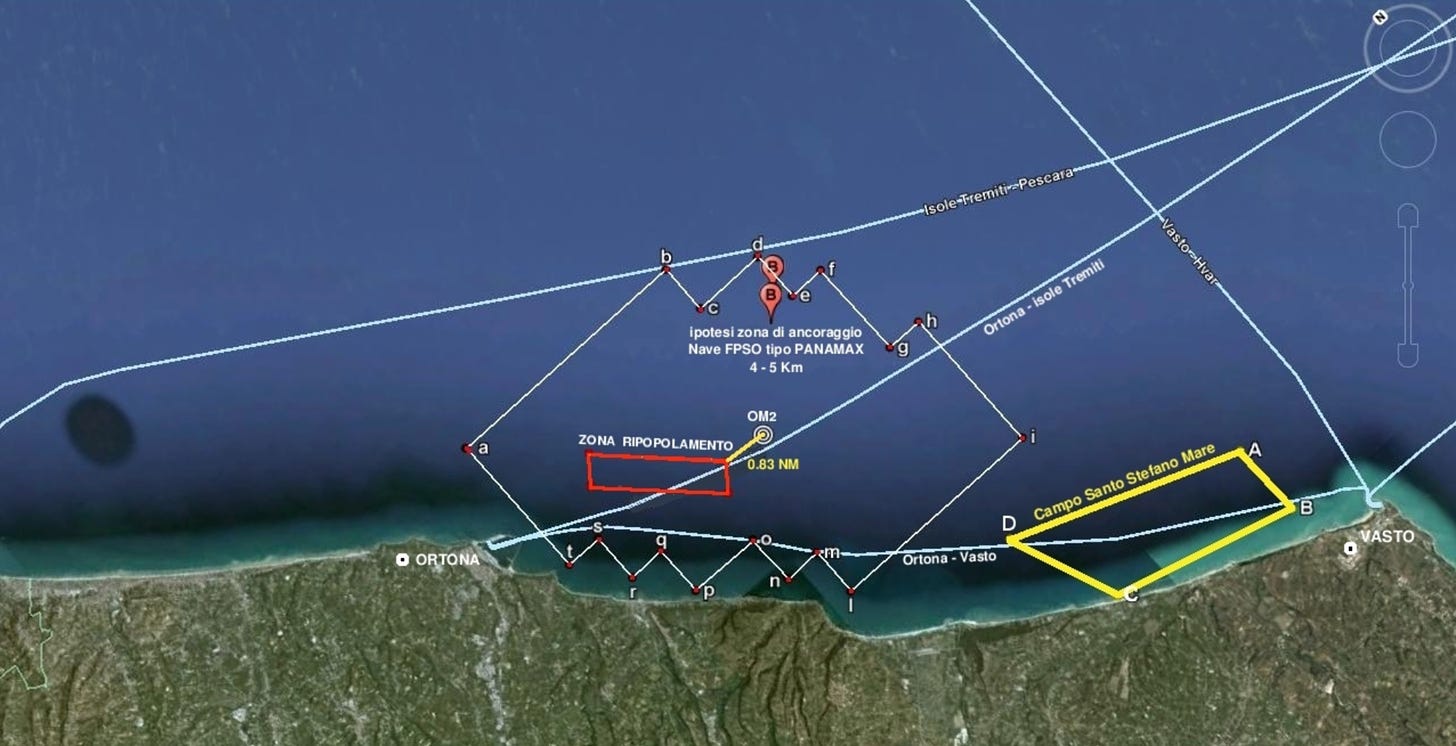

Capitalism’s focus on future returns on investment as the only future that matters is well illustrated by the story of oil company Rockhopper Exploration PLC and its failed exploration site at Ombrina Mare near the Adriatic coast of Italy.

The company’s drilling project on that stunningly beautiful coast met resistance from the time of its concession in 2008. This included, as Liliana Doganova records,

massive environmental demonstrations in the Abruzzo region, a request for a referendum by ten Italian regions and ultimately, legislative decrees that banned near-shore projects like this one.

Finally the concession was rejected by the Italian government.

Rockhopper Exploration – a UK-based company – was not deterred.

In 2017 it launched arbitration proceedings against Italy, demanding compensation for the company’s investment in the Ombrina Mare project. The total exploration cost to Rockhopper and its shareholders was just €2 million. The company had created no infrastructure. There were no oil drilling installations to be dismantled. There were no workers to lay off, no contracts to terminate.

Despite these facts, by using the investor’s own Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis, the arbitration tribunal awarded Rockhopper €184 million as compensation for the loss of future capital gains due to popular, democratic dissent.

The tribunal’s line of thought was that the future that mattered most was not the Adriatic coastline or its citizens, but Rockhopper’s.

Rockhopper, the investor whose future imagined capital gains far outstripped imagined costs (the discounted rate) and was therefore awarded €184 million of real money.

The inherent contradictions in the Fisher’s ‘principle of capitalisation’

The Rockhopper story illustrates the contradiction at the heart of Fisher’s analysis of capitalism’s relationship to time. The landmark publication The Economics of Climate Change: the Stern Review laid bare that contradiction in 2006. It revealed the incompatibility of the use of discounting in Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) to the task of tackling the climate and ecological crises. Because when viewed through capitalism’s Fisher lens of DCF, ambitious climate policies proved pointless and worthless. The Review noted that

their eventual benefits are so distant in time that they become heavily discounted and can barely weigh against .. initial costs, most of which are much more proximate in time.

Instead, the Stern review proposed using discount rates close to zero in order to make the future count as much as the present, coming to the remarkable (for capitalism) conclusion that we must

treat welfare of future generations on a par with our own.

Stern’s calculations were attacked by the notorious climate-denier, and adviser to the UN’s IPCC, William Nordhaus. (For more on Nordhaus see my 28 August, 2023 post, Nordhaus, ‘Refuseniks” “Frontierniks” and “Limitniks”).

Nordhaus argued that the discount rate that determines the

efficient balance between the cost of emissions reductions today and the benefit of reduced climate damage in the future” should be “the return on capital”…which measures net yield on investment in capital, education and technology ..observable in the marketplace..

and far higher than the zero rate applied by Stern.

Those are the economic arguments that are responsible for capitalism’s disregard of the threats facing humanity. It explains the lack of preparation for climate breakdown by most governments. Only ten years ago, economists advising the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) came to this conclusion: 1

For most economic sectors, the impact of climate change will be small relative to the impacts of other drivers (medium evidence, high agreement).

Changes in population, age, income, technology, relative prices, lifestyle, regulation, governance, and many other aspects of socioeconomic development will have an impact on the supply and demand of economic goods and services that is large relative to the impact of climate change. {10.10} (Emphasis added)2

Thankfully the Stern report stood apart from mainstream economists – and the IPCC. Its authors recognised that investment as a cost incurred now is vital to avoid and protect against the risks spelled out by scientists of very severe consequences in the future. Those scientists think we are now well past tipping points – including the burning of the Amazon forest that was once a carbon sink; and signs we are moving closer to a tipping point for the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

“A lot of discussion is, how should agriculture prepare for this,” the scientist René van Westen said.

“But a collapse of the heat-transporting circulation is a going-out-of-business scenario for European agriculture, he added.

“You cannot adapt to this. There’s some studies of what happens to agriculture in Great Britain, and it becomes like trying to grow potatoes in Northern Norway.

That should worry the Labour government far more than the state of the oil industry. For an AMOC collapse would clearly pose a critical challenge to food security as the OECD warned as far back as 2021.

Such a collapse combined with Climate Change would have a catastrophic impact.

An impact that current and future investors in Carbon Capture Technology refuse to face.

1

Those economists were: Coordinating Lead Authors:Douglas J. Arent (USA), Richard S.J. Tol (UK) Lead Authors: Eberhard Faust (Germany), Joseph P. Hella (Tanzania), Surender Kumar (India), Kenneth M. Strzepek (UNU/USA), Ferenc L. Tóth (IAEA/Hungary), Denghua Yan (China)

2

I am grateful to Professor Steve Keen for these references.

No comments:

Post a Comment