(RNS) — The Pew Research Center’s annual report on government restrictions on religion highlights that governmental attacks on religion and social hostility toward religion usually ‘go hand in hand.’

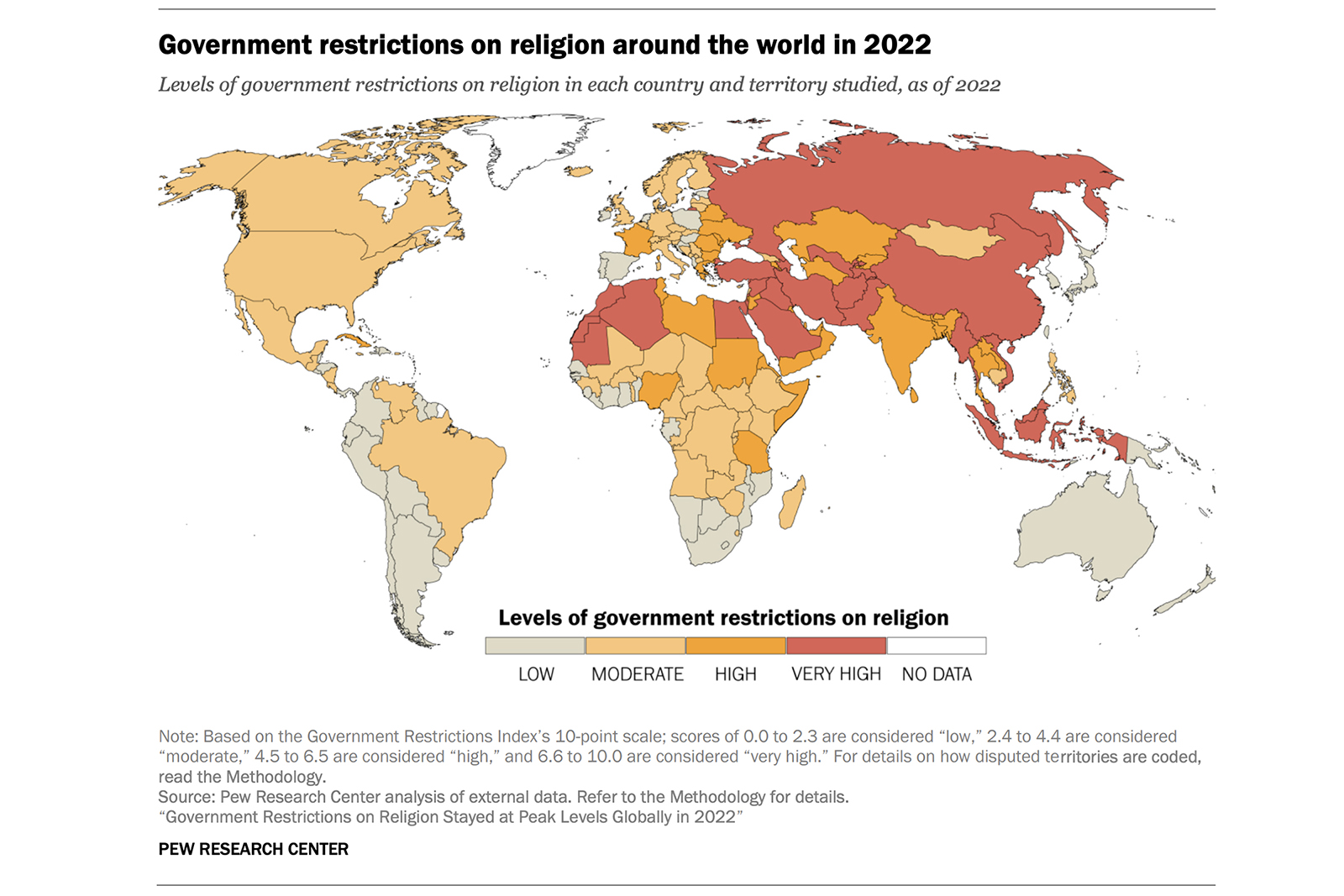

“Government restrictions on religion around the world in 2022” (Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center)

Fiona André

December 18, 2024

RNS

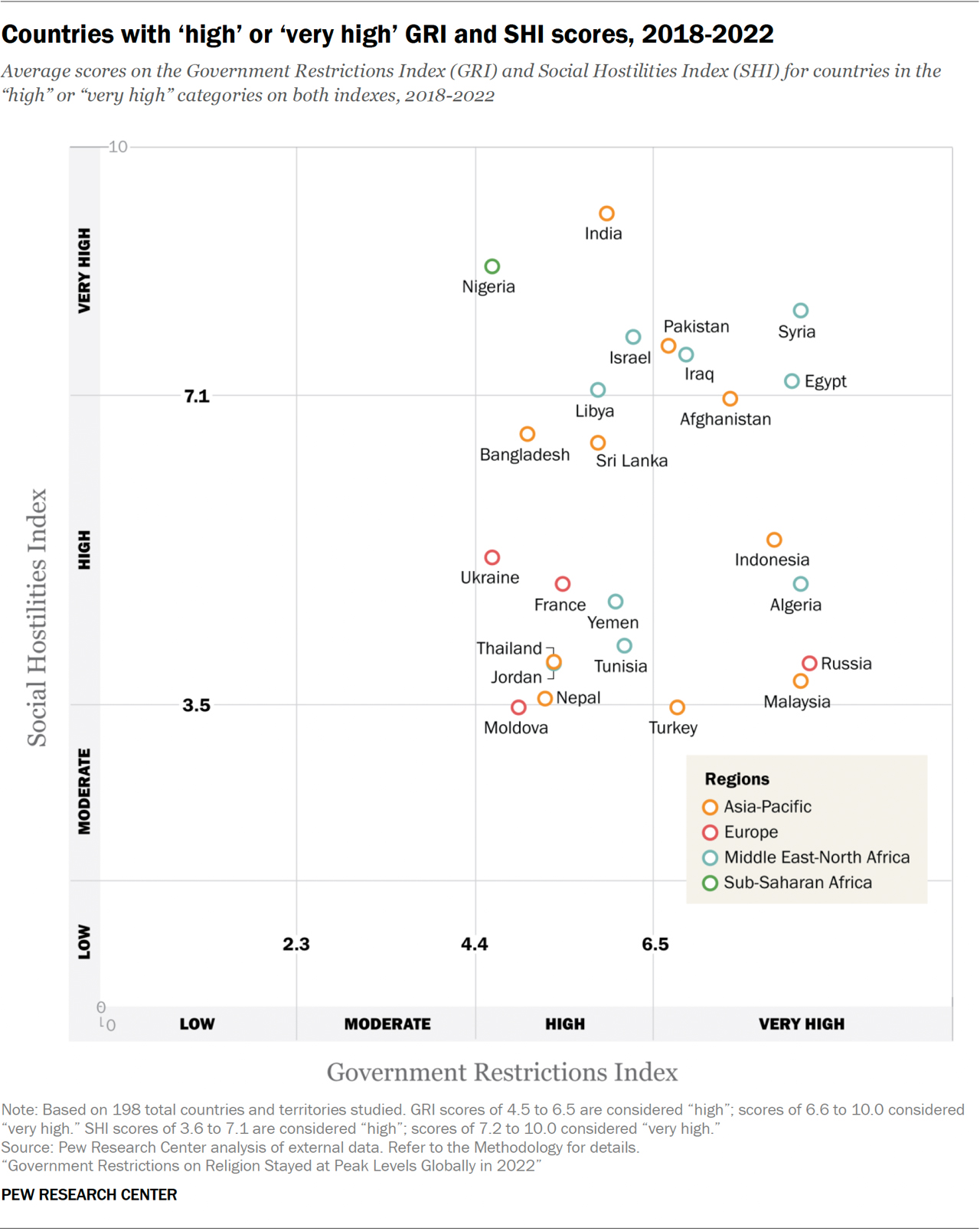

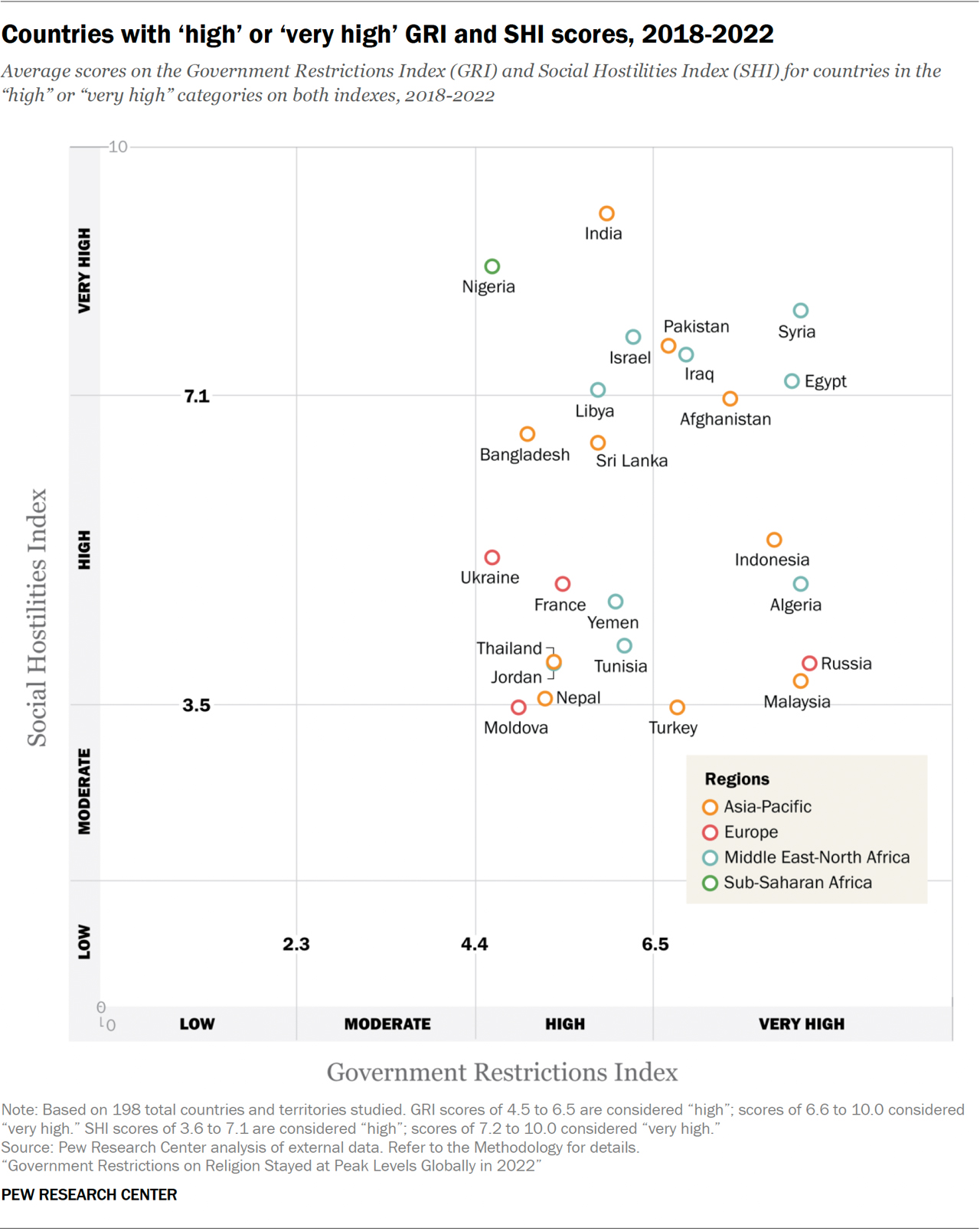

(RNS) — A report by Pew Research Center on international religious freedom named Egypt, Syria, Pakistan and Iraq as the countries where both government restrictions and social hostility most limit the ability of religious minorities to practice their faith.

Governmental attacks and social hostility toward various religions usually “go hand in hand,” said the report, the 15th annual edition of a report that tracks the evolution of governments restrictions on religion.

The report uses two indexes created by the center in 2007, the Government Restrictions Index and the Social Hostilities Index, to rank countries’ levels of government restrictions on religion and attitudes of societal groups and organizations toward religion.

The GRI focuses on 20 criteria, including government efforts to ban a faith, limit conversions and preaching, and preferential treatment of one or many religious groups. The SHI’s 13 criteria take into account mob violence, hostilities in the name of religion and religious bias crimes.

The study looks at the situation in 198 countries in 2022, the latest year for which data are available from such agencies as the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, the U.S. Department of State and the FBI. The report also contains findings from independent and nongovernmental organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Anti-Defamation League, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.

In total, 24 countries were given high or very high GRI scores (4.5 or higher on a scale of 10) and high or very high SHI scores (higher than 3.6 out of 10). Close behind the four countries that scored very high on both scales were India, Israel and Nigeria.

“Countries with ‘high’ or ‘very high’ GRI and SHI scores, 2018-2022” (Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center)

Thirty-two other countries, including Turkistan, Cuba and China, scored high or very high on government restrictions, but low or moderate on social hostility. Most were rated as “undemocratic” and “authoritarian” by The Economist magazine’s Democracy Index.

“Such regimes may tightly control religion as part of broader restrictions on civil liberties,” reads the report. Many Central Asian countries and post-Soviet countries fell into that category, noted Samirah Majumdar, the report’s lead researcher.

Besides ranking countries where religions were under the most pressure, the team that put together the report, part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project, tried to determine “whether countries with government restrictions tend to be places where they also have social hostilities; Do countries with relatively few government restrictions also tend to be places where they have relatively few social hostilities?” explained Majumdar.

Majumdar said that the results were inconclusive. “We can’t exactly determine a causal link, but there are some patterns we were able to observe in the different groupings,” she said. “A lot of those countries have had sectarian tensions and violence reported over the years. In some cases, government actions can go hand in hand with what is happening socially in those countries.”

Countries with low or moderate scores on both indexes — a GRI no higher than 4.4 out of 10 and an SHI between 0 and 3.5 — usually had populations under 60 million inhabitants.

(RNS) — A report by Pew Research Center on international religious freedom named Egypt, Syria, Pakistan and Iraq as the countries where both government restrictions and social hostility most limit the ability of religious minorities to practice their faith.

Governmental attacks and social hostility toward various religions usually “go hand in hand,” said the report, the 15th annual edition of a report that tracks the evolution of governments restrictions on religion.

The report uses two indexes created by the center in 2007, the Government Restrictions Index and the Social Hostilities Index, to rank countries’ levels of government restrictions on religion and attitudes of societal groups and organizations toward religion.

The GRI focuses on 20 criteria, including government efforts to ban a faith, limit conversions and preaching, and preferential treatment of one or many religious groups. The SHI’s 13 criteria take into account mob violence, hostilities in the name of religion and religious bias crimes.

The study looks at the situation in 198 countries in 2022, the latest year for which data are available from such agencies as the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, the U.S. Department of State and the FBI. The report also contains findings from independent and nongovernmental organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Anti-Defamation League, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.

In total, 24 countries were given high or very high GRI scores (4.5 or higher on a scale of 10) and high or very high SHI scores (higher than 3.6 out of 10). Close behind the four countries that scored very high on both scales were India, Israel and Nigeria.

“Countries with ‘high’ or ‘very high’ GRI and SHI scores, 2018-2022” (Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center)

Thirty-two other countries, including Turkistan, Cuba and China, scored high or very high on government restrictions, but low or moderate on social hostility. Most were rated as “undemocratic” and “authoritarian” by The Economist magazine’s Democracy Index.

“Such regimes may tightly control religion as part of broader restrictions on civil liberties,” reads the report. Many Central Asian countries and post-Soviet countries fell into that category, noted Samirah Majumdar, the report’s lead researcher.

Besides ranking countries where religions were under the most pressure, the team that put together the report, part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project, tried to determine “whether countries with government restrictions tend to be places where they also have social hostilities; Do countries with relatively few government restrictions also tend to be places where they have relatively few social hostilities?” explained Majumdar.

Majumdar said that the results were inconclusive. “We can’t exactly determine a causal link, but there are some patterns we were able to observe in the different groupings,” she said. “A lot of those countries have had sectarian tensions and violence reported over the years. In some cases, government actions can go hand in hand with what is happening socially in those countries.”

Countries with low or moderate scores on both indexes — a GRI no higher than 4.4 out of 10 and an SHI between 0 and 3.5 — usually had populations under 60 million inhabitants.

RELATED: For 25th year, State Department reports on threats, triumphs in religious freedom

The index factors the same criteria over the years, and the team relies on the same sources, allowing for comparisons from one year to another. From 2021 to 2022, median GRI and SHI scores stayed the same, but in sub-Saharan Africa, the GRI rose from 2.6 to 3.0 out of 10. In Middle Eastern and North African countries, the index went from 5.9 to 6.1.

Among the 45 countries that presented high or very high SHI scores, Nigeria was the first of the seven countries with very high levels, a result linked to gang violence against religious groups and violence by militant groups Boko Haram and ISIS-West Africa, which rages in the Sahel desert.

RELATED: Study: Social hostility to religion declines, but government restrictions rise

Iraq, which ranks among the countries with both high GRI and SHI, also finds itself among the countries with the highest social hostilities, and has seen its social hostility score increase. The report attributed this to violence against religious minorities imprisoned by Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Forces. It also cited a 2024 Amnesty International report on outbreaks of gender-based violence in Iraqi Kurdistan, with many occurrences of women being killed by male family members, sometimes for converting to another religion.

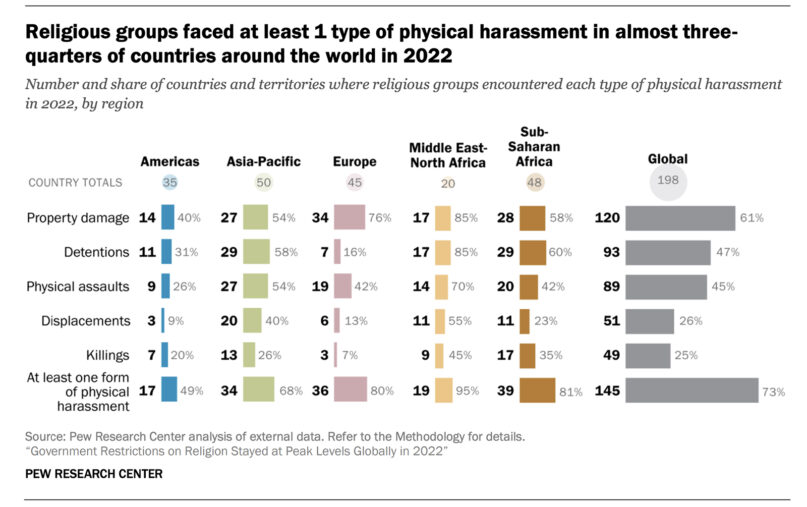

“Religious groups faced at least 1 type of physical harassment in almost three-quarters of countries around the world in 2022” (Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center)

According to the report, physical harassment against religious groups by government or social groups peaked in 2022. This category covered acts from verbal abuse to displacements, killings or damage to an organization’s property. The study highlighted 26,000 displaced people from Tibetan communities in China and continued gang violence targeting religious leaders by Haitian gangs.

Overall, the number of countries where physical harassment took place increased to 145 in 2022, against 137 countries in 2021.

New documentary tells America’s story of religious freedom

(RNS) – ‘The film humanizes that history through the stories of brave citizens who defended the right to exercise their most deeply held beliefs,’ explained co-director John Paulson.

Richard Brookhiser, center, hosts the “Free Exercise: America’s Story of Religious Liberty" historical documentary. (Courtesy photo)

Fiona André

December 17, 2024

(RNS) — A new documentary, “Free Exercise: America’s Story of Religious Liberty,” tells the story of religious freedom through the experience of six religious groups — Quakers, Baptists, Black churches, Catholics, Mormons and Jews — and the persecutions they endured. The film shows that, far from being a principle set in stone, the First Amendment’s free exercise clause has evolved and been reinforced by groups’ efforts to gain the right to practice their faith.

Religious freedom is “a process” that “always needs to be revisited and maintained,” said the film’s host, National Review columnist Richard Brookhiser. “The documentary shows people what this story has been, what this process has been, what the principles are, how they’ve been worked out in the world.”

The documentary’s two hours are broken into six sections, each focusing on one of the religious groups and an episode from its history that marked its fight for religious rights. In two hours, the documentary takes viewers on a journey from the plains of Utah, in the segment on the 19th-century exodus by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to a Rhode Island synagogue that George Washington addressed in a letter supporting the United States’ early Jewish American community, to a station on the Underground Railroad where enslaved African Americans worshipped in secret.

RELATED: Harriet Tubman, in the movie and real-life guided by faith in the fight for freedom

“Free Exercise: America’s Story of Religious Liberty” film poster. (Courtesy image)

The film employs many historical reenactments and archival material to make the stories lively and relatable, as it follows Brookhiser to various locations where crucial events took place.

The filmmakers lionize those who stood up for religious freedoms over the centuries, telling the stories of “brave citizens who defended the right to exercise their most deeply held beliefs,” said the film’s co-director, John Paulson.

One example is an inspiring but little-known chapter in the founding of New York, known as the Flushing Remonstrance. In a 1657 letter, New Amsterdam’s Dutch settlers urged Peter Stuyvesant, the administrator of New Netherlands, to lift his ban on Quaker worship, a common restriction targeting what was then considered a fringe Christian sect.

That non-Quakers citizens would stand up for their neighbors’ rights to practice their faith exemplified how religious freedom had been the work of many, religious and nonreligious, said Brookhiser. “These 30 ordinary men said, ‘These people are being oppressed by you. Lay off them. We are standing up for their freedom, for their ability to worship.’ It was just very moving,” he said.

RELATED: Religious freedom was meant to protect, not bludgeon. What happened?

A section on the founding of the African Methodist Episcopal Church highlights the Black church’s history as space for Black Americans to organize and to resist first slavery and, later, racism. The film’s history of American Judaism tells the story of antisemitism in America, relating the case of Leo Frank, a factory worker in Atlanta who was wrongly convicted of murder in 1913 and lynched two years later after his appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was rejected. Frank’s three-week show trial prompted the creation of the Anti-Defamation League.

The documentary also features a segment on a conference organized by the Becket Fund with legal experts invited to discuss how courts and legislatures have protected and broadened the First Amendment in the 21st century. (Thomas D. Lehrman, the film’s executive producer, was a Becket Fund board member for eight years.)

The movie concludes with a section dedicated to the future of religious freedom, raising questions about how our understanding of religious freedom will continue to evolve as newer arrivals to the United States expand the faith footprints of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and other global religions.

It also raises questions on how much society should accommodate free exercise and how much the government should intervene to protect citizens’ beliefs.

“Free exercise is an epochal principle. But even the greatest principles are not self-enacting; they need to be understood and upheld by every generation,” said Brookhiser.

Last week, the film was released on streaming platforms, including Apple TV, Amazon Prime Video, Vimeo and Google Play. The movie premiered on PBS stations in the fall.

(RNS) – ‘The film humanizes that history through the stories of brave citizens who defended the right to exercise their most deeply held beliefs,’ explained co-director John Paulson.

Richard Brookhiser, center, hosts the “Free Exercise: America’s Story of Religious Liberty" historical documentary. (Courtesy photo)

Fiona André

December 17, 2024

(RNS) — A new documentary, “Free Exercise: America’s Story of Religious Liberty,” tells the story of religious freedom through the experience of six religious groups — Quakers, Baptists, Black churches, Catholics, Mormons and Jews — and the persecutions they endured. The film shows that, far from being a principle set in stone, the First Amendment’s free exercise clause has evolved and been reinforced by groups’ efforts to gain the right to practice their faith.

Religious freedom is “a process” that “always needs to be revisited and maintained,” said the film’s host, National Review columnist Richard Brookhiser. “The documentary shows people what this story has been, what this process has been, what the principles are, how they’ve been worked out in the world.”

The documentary’s two hours are broken into six sections, each focusing on one of the religious groups and an episode from its history that marked its fight for religious rights. In two hours, the documentary takes viewers on a journey from the plains of Utah, in the segment on the 19th-century exodus by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to a Rhode Island synagogue that George Washington addressed in a letter supporting the United States’ early Jewish American community, to a station on the Underground Railroad where enslaved African Americans worshipped in secret.

RELATED: Harriet Tubman, in the movie and real-life guided by faith in the fight for freedom

“Free Exercise: America’s Story of Religious Liberty” film poster. (Courtesy image)

The film employs many historical reenactments and archival material to make the stories lively and relatable, as it follows Brookhiser to various locations where crucial events took place.

The filmmakers lionize those who stood up for religious freedoms over the centuries, telling the stories of “brave citizens who defended the right to exercise their most deeply held beliefs,” said the film’s co-director, John Paulson.

One example is an inspiring but little-known chapter in the founding of New York, known as the Flushing Remonstrance. In a 1657 letter, New Amsterdam’s Dutch settlers urged Peter Stuyvesant, the administrator of New Netherlands, to lift his ban on Quaker worship, a common restriction targeting what was then considered a fringe Christian sect.

That non-Quakers citizens would stand up for their neighbors’ rights to practice their faith exemplified how religious freedom had been the work of many, religious and nonreligious, said Brookhiser. “These 30 ordinary men said, ‘These people are being oppressed by you. Lay off them. We are standing up for their freedom, for their ability to worship.’ It was just very moving,” he said.

RELATED: Religious freedom was meant to protect, not bludgeon. What happened?

A section on the founding of the African Methodist Episcopal Church highlights the Black church’s history as space for Black Americans to organize and to resist first slavery and, later, racism. The film’s history of American Judaism tells the story of antisemitism in America, relating the case of Leo Frank, a factory worker in Atlanta who was wrongly convicted of murder in 1913 and lynched two years later after his appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was rejected. Frank’s three-week show trial prompted the creation of the Anti-Defamation League.

The documentary also features a segment on a conference organized by the Becket Fund with legal experts invited to discuss how courts and legislatures have protected and broadened the First Amendment in the 21st century. (Thomas D. Lehrman, the film’s executive producer, was a Becket Fund board member for eight years.)

The movie concludes with a section dedicated to the future of religious freedom, raising questions about how our understanding of religious freedom will continue to evolve as newer arrivals to the United States expand the faith footprints of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and other global religions.

It also raises questions on how much society should accommodate free exercise and how much the government should intervene to protect citizens’ beliefs.

“Free exercise is an epochal principle. But even the greatest principles are not self-enacting; they need to be understood and upheld by every generation,” said Brookhiser.

Last week, the film was released on streaming platforms, including Apple TV, Amazon Prime Video, Vimeo and Google Play. The movie premiered on PBS stations in the fall.

No comments:

Post a Comment