‘In the Western European left, there’s a desire to put up a wall and ignore what’s happening in the east’

First published in Spanish at Ctxt. Translation by Adam Novak from Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières.

Denys Gorbach (Kryvyi Rih, 1984) is a sociologist. The research from his doctoral thesis at Sciences Po (Paris) is contained in the book The Making and Unmaking of Ukrainian Working Class (Berghahn, 2024), which recounts how economic changes altered the values of the working class in Ukraine, focusing on his city, Kryvyi Rih, in the south-east of the country. Kryvyi Rih was considered the “iron heart of the USSR”. It has several mines and a large steelworks. It is the birthplace of President Zelensky.

Gorbach also became involved in helping Ukrainian refugees in France and studied their situation. He currently researches the social concept of conspiracy theories at Lund University (Sweden). He spoke to CTXT.es by video call to discuss Ukrainian politics and the war.

In the book you argue that post-Soviet Ukraine, in its privatisation process, did not fully integrate into the neoliberal economy and that “a socialist appearance wrapped capitalist practices”.

Well, it depends on what we understand by neoliberal. There wasn’t large-scale privatisation with foreign investors as occurred in Poland, Hungary or the Baltic countries, for example. The ruling class was afraid.

I was surprised to find a literal confirmation of this idea in the writings of those who participated in these events, such as an adviser to President Kuchma,1 who governed during the era of major privatisations. These people had been trained in Marxist political economy during the Soviet era and tried to use that knowledge to build the capitalist economy. This adviser wrote that their explicit objective was to create a Ukrainian national bourgeoisie before opening the market to foreign capitalists.

This ruling class, which was building itself, maintained the existing moral economy, a moral economy that we can call socialist, supposedly socialist, supposedly Soviet, which implied mutual obligations between rulers and ruled.

And some of these restrictions have been maintained until today, for example, there are still restrictions regarding land ownership, if I’m not mistaken.

The removal in 2020 of the moratorium on land purchase and sale (in force since 2001) was one of the major neoliberal steps that Zelensky took. Even Poroshenko,2 the president with the most neoliberal rhetoric, decided not to do this. And when Zelensky did it, Poroshenko opposed it and organised protests against it.

Land ownership was already privatised, but there exists this fear that, if you allow it to be bought and sold like any other good, large companies will be able to monopolise it.

It’s a taboo subject in popular consciousness. It’s also present in the popular imagination about the Second World War. Since my childhood I’ve heard stories that the Germans took the land of Ukraine away in trains to Germany. It’s probably not true, but it shows the value we give to land.

So yes, it was a very problematic issue. And Zelensky finally did it. But even with all the pressure from international financial institutions that pushed him to do it, he established a series of limitations. (According to the law, the acquisition of land by foreigners or entities with foreign capital must be approved by referendum.)

He also passed a harsh labour reform in the middle of the war, in 2022.

Yes, I think this can be explained within the framework of the shock doctrine, proposed by Naomi Klein.3

Zelensky and his team are part of a new generation of politicians who have already grown up under capitalist conditions. I get the impression that they are sincerely against the oligarchs and are also against the trade unions, because they see both institutions as obstacles to the development of the free market. So they’ve done some things to fight against the concentration of capital in the oligarchy, but they’ve also gone against the trade unions and the socialist regulation, so to speak, of labour relations.

In the midst of war, obviously this wasn’t Zelensky’s greatest concern, but Halyna Tretiakova, a parliamentarian from his party who chairs the Social Policy Committee, took advantage of the occasion to push through three terrible labour liberalisation laws in 2022.

There’s been much talk of the two different political identities that exist in Ukraine, linked to the western and eastern regions. In the book you call them “ethnic Ukrainian” and “Eastern Slavic” identity, but I think you’re somewhat critical of the way these identities are usually explained.

One of the criticisms I receive most is that I don’t nuance enough. You always have to put these terms in many inverted commas. The identity I call “ethnic Ukrainian” isn’t necessarily a matter of ethnic nationalism as such, it’s a set of vague political ideas that combines sympathy for the West, preference for a more liberal economic model and a more important role for the Ukrainian language. Opposed to this is another very, very complex set of ideas, what I call “Eastern Slavic”, which includes maintaining stronger ties with Russia and the post-Soviet world, being neutral on the language question or defending the status quo, which is the predominance of Russian, and perhaps greater regulation of the economy. I think it’s better not to call them “pro-Russian” because this isn’t necessarily true, especially since this war began. They often define themselves as non-nationalists, but I think it’s a form of nationalism that doesn’t recognise itself as such.

I keep looking for better words to describe this duality... It’s not a duality, it’s a spectrum, a continuum. It must be perceived with much scepticism.

Would you say this “Eastern Slavic” identity is closer to the left?

Again, it depends on what we understand by left.

Of course.

Of course, it’s closer to the left in terms of flags and symbols. The Soviet Union and all that. But this doesn’t always translate into support for equality policies. In Ukraine the left-wing parties moved very quickly to cultural politics.

You argue that those identities were exacerbated by the oligarchs for electoral purposes.

Yes, I try to explain that it’s not an ancient matter. In the 2000s, from the so-called Orange Revolution4 onwards, there were changes to the Constitution that gave more power to Parliament. So the capitalist class of oligarchs had to adapt. Before they went directly to the president. Now they had to invent parties to participate in politics. And those parties had to show some type of ideology. At first they tried to follow the typical European model with left and right, but they quickly realised it wasn’t worthwhile. It was easier to apply the lowest common denominator, which was national identities. Easy to convert into slogans, into television adverts. My argument is that this is how these two camps were formed. Then the more pro-Western, pro-Ukrainian language ones were called oranges.

You asked me if the more pro-Russian ones were more left-wing. Rhetorically yes, and they also defended the preservation of some welfare policies, but at the same time, in this camp was the most powerful fraction of the capitalists.

Because they were the ones who controlled the large industries?

Yes. The pro-Western fraction was like a second tier of the oligarchy.

When discussing these questions, the difference between the more industrial regions and the more agricultural ones is also usually mentioned.

Yes, in the south-east of Ukraine there’s a highly industrialised belt, very urban, with high population density. At macroeconomic level, these regions were the richest, the ones that produced most. Now we don’t know what’s going to happen, because they’re ageing industries and I can’t imagine capitalists queuing up to invest 50 kilometres from a front line, even if it weren’t active. So now the economic geography is changing, investments are concentrated in the west. I don’t know what’s going to happen to those millions of people who live from industry, who are somehow proud of it.

These regions where there was greater sympathy for Russia are the ones that the Russian invasion has most destroyed.

Yes, yes. Some people who are there, with whom I stay in contact, sympathised with Putin and feel it as a betrayal. The most “pro-Russian” said this wasn’t going to happen, that it was propaganda from Ukrainian nationalists.

And now they’re disappointed. Well, not only disappointed. They are victims. The greatest number of victims, the greatest destruction of infrastructure and housing, has occurred precisely in cities like Mariupol and Kharkiv.5

You yourself said you didn’t expect the Russian invasion.

Yes, I don’t mind admitting it. I’m one of those people who thought this wasn’t going to happen.

I’m still in a very large group chat with workers from the steelworks. In the book I talk a bit about that chat, about how politics invaded the conversations and many people felt rejection towards it.

The afternoon before the invasion there were still debates. They said things like “who do you take us for? Do you seriously think Putin is going to attack? Of course not”.

The next day, everyone moved on to talking about practical matters. What do we do? Where do we go? Very practical things about how to face something that twelve hours before they didn’t think was going to happen.

Sometimes journalists write that everyone has changed from the Russian language to Ukrainian. That’s only true, in part, amongst the intellectual middle classes in cities like Kyiv. In the army there are thousands of people speaking Russian. In a Russian-speaking region like mine, people reject this rhetoric.

In 2014, the government of Viktor Yanukovych decided not to sign an economic association agreement with the European Union and to negotiate with Russia. Ukraine had trade relations of similar importance with both blocs.

At that moment, yes. Ukraine as an economy had managed to maintain itself in an intermediate space between the two blocs. Approximately half of exports went to the European Union and the other half to the former Soviet Union. Exports to Russia and the former Soviet Union were high-tech, like helicopters, engines or train locomotives. Exports to the European Union were raw materials, because Ukrainian industry couldn’t compete with companies like Alstom or Siemens, but both were important.

Today President Yanukovych is remembered as very pro-Russian, but in reality he spent most of his presidency under the European Union banner. Not because he was a convinced Europeanist, but because this was the consensus decision amongst the elites. The problem is that those elites also depended on energy, on cheap oil and gas from Russia.

I was an economic journalist at that time, so I remember it very clearly. Every week I wrote the same thing. Putin says Ukraine must pay more for gas. The International Monetary Fund says Ukraine must liberalise energy prices for households. The Ukrainian government says “my god, we can’t do this”. It says “we have to maintain our relationship with Russia, but Russia has to understand that we want to sign this treaty with the EU”.

From 2012 Russia started a sequence of trade wars. One month it was milk, the next locomotives. It was quite explicit. It was like saying “this is just the beginning of what awaits you if you sign that treaty”.

What did the Ukrainian government expect, the Ukrainian capitalist class, at that moment? They expected that the European Union would give them some type of economic support or compensation for what they were going to lose, for the rise in gas prices. And it never happened. There’s a video of Yanukovych talking with Merkel at the Vilnius summit.6 He tries to say with body language that he’s in a complicated situation. And the EU’s response was no, that they couldn’t do any of that. Then Yanukovych turned towards Russia. It was all much more fluid and contradictory than the story tells.

Then the revolt known as Euromaidan erupted and, subsequently, the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the independence uprisings in Donetsk and Luhansk.

The official viewpoint in Ukraine is that everything was completely organised by Russia. There’s also the other viewpoint that it was completely organised by the CIA. If you’re a specialist in international relations, it’s normal that you see things that way. I’ve always been more interested in social processes. In Ukraine it’s totally taboo to speak of civil war, you get cancelled, but from an analytical viewpoint, I don’t see any problem in saying that yes, between 2014 and 2022 there was a conflict that had elements of civil war, with strong external influences. For anyone who wants to delve deeper, I recommend the book that Serhiy Kudelia has published. In that conflict some 14,000 people died in total, amongst combatants from both sides and civilians.

We tend to analyse the past from the knowledge of the present, so it’s normal to see the events of 2014 as precursors to those of 2022. But I don’t think it was so linear, there wasn’t a master plan from Putin or anyone.

Some analysts point to Russia’s concern for its security due to NATO’s eastward expansion as one of the explanations for the invasion. Do you think this factor played a role in the Russian government’s decision?

I think NATO has had excessive prominence in the analyses. Of course this eastward expansion occurred, but it was many years ago. I find the way people like Mélenchon7 talk about the 2008 Bucharest Summit striking. I covered it as a journalist and I have a totally different memory. The Ukrainian delegation arrived with great hopes of obtaining a Membership Action Plan8 for NATO. And they were rejected. They were told the typical polite phrases of yes, of course, later on, maybe if so, come on, goodbye.

Now those phrases are quoted as proof that NATO was very interested in Ukraine, but NATO supporters at that time were absolutely outraged. There had been public discussions, protests against it, but after that the debate was closed. Until 2014, when the war in Donbas began, with foreign troops present on the territory.

What has happened from 2022 onwards is that NATO has added thousands more kilometres of border with Russia because Finland has joined. And nobody in Russia seems very concerned, the troops aren’t there.

If I’m not mistaken, the far right has never obtained relevant representation in Ukraine’s Parliament, but they have made themselves noticed in the streets and it seems the war has strengthened them. What’s the situation?

Yes, it’s a paradox. In elections they usually obtain ridiculous results, 1% or 2% of the vote. The maximum they reached (the far-right nationalist party Svoboda9) was 10% in the 2012 elections, when Yanukovych considered that such an opposition suited him. But it’s not honest to cite those data and say that nothing’s happening with the far right.

As you’ve said, they’re strong in the streets. I call them “entrepreneurs of political violence”. They’ve accumulated resources and know how to deploy them.

We can go back to the Maidan or Euromaidan of 2014.10 There were hundreds of thousands of people gathered in that large square. The majority were like the people I describe in the book, without a very formed ideology. They rejected corruption and the oligarchs and wanted to live like Europeans, that is, with money. Only a small minority belonged to far-right organisations. But they were the most prepared, they weren’t afraid to attack the police, they had combat skills, they knew how to prepare Molotov cocktails.

They built political capital in Maidan and in the war in Donbas, where they were the most motivated fighters in a disorganised army. And now they reinforce their reputation in this new war, although this time the government has done a better job of limiting their influence.

Unfortunately, they’re over-represented in the media. To begin with, by themselves, who are the first interested in promoting themselves. But also by Russian media and those who sympathise with Putin in the West. And sometimes the Ukrainian government also does stupid things.

The war has already lasted three years. I get the impression it’s been longer than many people thought at the beginning. I know this question is impossible to answer rigorously, but, according to what you perceive, what do people want? Can it be different from what the government wants?

My direct experience is with refugees in France. In 2023, when we started working with them, they were all very optimistic, they thought victory was near. And at the beginning they must have been even more optimistic because many people left their homes in Ukraine thinking it would be a matter of two weeks, like a holiday. Obviously, this is no longer the case. Now they understand they are refugees.

The same has happened in Ukraine. The initial reaction was total mobilisation, for better and for worse. I think the government made a mistake in fostering exaggerated optimism, that idea that they were going to recover Crimea, well... By the end of 2023, spirits began to change, when the counter-offensive didn’t produce results.

Then Trump returned to the presidency of the United States. The government and intellectuals in Ukraine perceived it as a disaster. But amongst ordinary people, from what I’ve been told, there was that implicit hope that a bad ending would be better than this horrible situation without end. Even if concessions had to be made. However, when Trump announced his proposal, even people who were very unpatriotic, so to speak, found it too much. Leaving Russia territories it hasn’t occupied for now, ceding natural resources to Trump...

Now everyone wants the war to end. This doesn’t form part of the Ukrainian government’s official discourse, but I think they too would be willing to make territorial concessions, provided stable peace conditions were guaranteed.

This is what’s missing from all the proposals so far. Some guarantee that they won’t start again in a couple of years. This would be catastrophic because if you sign an agreement now and in two years the invasion starts again, it’s assumed you won’t be able to count on the same support from the United States and the European Union.

Then, if you look at the European elites, there are people who say they’re willing to fight Russia to the last Ukrainian. It’s true that all parties have their own interests. It doesn’t seem to me that the European Union is guided by hatred of Russia or fanaticism in favour of Ukraine. I think they’re readjusting their policies, they want to increase their military capabilities for the next decade, they talk about a plan for 2030... and for that, meanwhile they sacrifice Ukraine, they let it bleed.

It looks bleak.

Yes. Bad outlook. I was a left-wing activist in Ukraine and I still consider myself a left-wing activist. When I talk with leftists here, in Western Europe, it strikes me as odd because they tend to reject the subject. They say it’s all propaganda. And yes, it is, which is why I miss more analysis from a socialist perspective. It’s all slogans. Right, you love peace. You hate war. Of course, we all love peace but...

Did you expect something different from the left?

The thing is I don’t have answers myself either. But it would be good to have a real debate about what to do beyond simple repetition of slogans. What I see most is a desire to put up a wall and ignore everything that’s happening in the east. And many people don’t realistically evaluate their own political positions.

If everything is already fascism, we don’t have to worry about it getting worse. Do you really think the political regimes in the European Union are exactly the same as Russia’s? Or would you prefer to live under a regime more like that one?

On the other hand, if you’re such an activist that you want everything to explode because then revolution will be possible, think about it a bit. Imagine a real scenario of war and chaos. Is it likely that your sector of the left will grow and obtain political power? Or might there be some fascist group in your country that’s better positioned? What will emerge from this chaos that you hope will arrive?

- 1

Leonid Kuchma, President of Ukraine 1994-2005

- 2

Petro Poroshenko, President of Ukraine 2014-2019

- 3

Canadian author and activist whose book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (2007) analyses how economic crises and disasters are exploited to implement free-market policies

- 4

Mass protests in Ukraine in 2004-2005 following disputed presidential elections, leading to a revote that brought Viktor Yushchenko to power.

- 5

Major industrial city in north-eastern Ukraine, the country’s second-largest city.

- 6

November 2013 EU Eastern Partnership summit in Lithuania where Ukraine was expected to sign the Association Agreement.

- 7

Jean-Luc Mélenchon, French left-wing politician and leader of La France Insoumise.

- 8

NATO programme designed to assist aspiring member countries.

- 9

Ukrainian nationalist party founded in 1991, originally called the Social-National Party of Ukraine.

- 10

Mass protests in Kyiv from November 2013 to February 2014, initially sparked by the government’s decision not to sign the EU Association Agreement, leading to President Yanukovych’s removal.

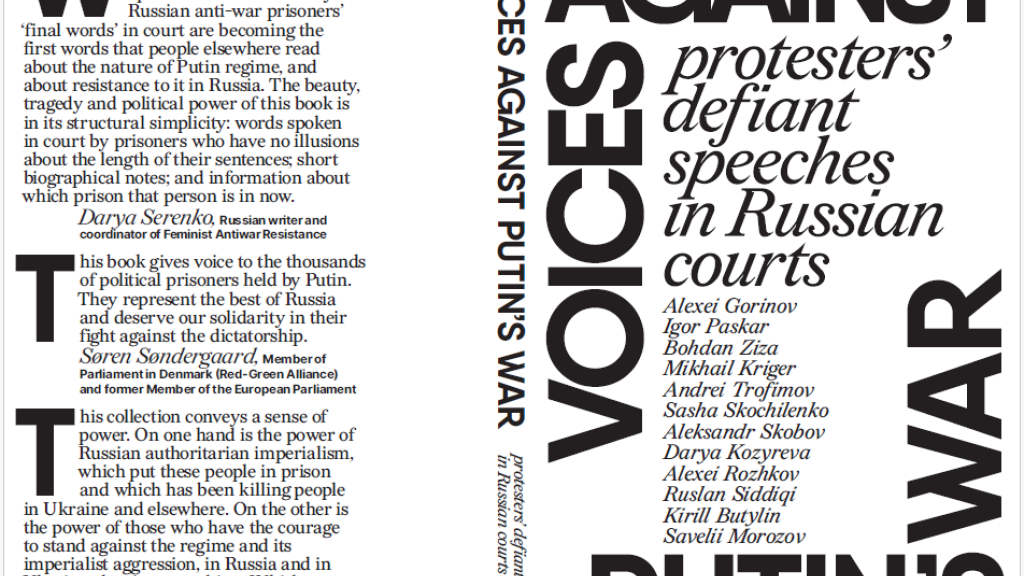

The courtroom rebels standing up to warmonger Putin

First published at European Network for Solidarity with Ukraine.

At the heart of Voices Against Putin’s War are ten speeches made in court by people who opposed Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, and were arrested and tried for doing so. Most of them are now serving long jail sentences, for “crimes” fabricated by Vladimir Putin’s repressive machine. Along with the speeches, we include: other public declarations — social media posts, letters and interviews — in which the protagonists made their case; statements by two more persecuted activists, made outside court; and a summary of 17 other anti-war speeches in court. We hope that, by publishing these translations in English, these resisters’ motivations will become known to a wider audience.

Chapters 1-10 are each devoted to one protester, are arranged chronologically by the date of the protester’s first conviction. United in their opposition to the Kremlin’s war, they divide roughly into four groups.

First is Bohdan Ziza (chapter 3), who lived not in Russia but in Ukraine — in Crimea, which has been occupied by Russian forces since 2014. In 2022 Ziza filmed himself splashing paint in the colours of the Ukrainian flag on to a municipal administration building. He was tried in a Russian military court and is serving a 15-year sentence.

Second are two young women from St Petersburg, Sasha Skochilenko (chapter 6, pictured above) and Darya Kozyreva (chapter 8), prosecuted for the most peaceful imaginable protests against the war. Skochilenko, who posted anti-war messages on labels in a supermarket, was freed after more than two years behind bars, in August 2024, as part of a prisoner swap between Russia, Belarus and several Western countries. Kozyreva is serving a two-and-a-half year sentence, essentially for quoting Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine’s national poet, in public.

Third are three young men who deliberately damaged property, but not persons, to draw their fellow Russians’ attention to the anti-war cause. Igor Paskar (chapter 2) firebombed an office of the Federal Security Service (FSB). Alexei Rozhkov (chapter 9) firebombed a military recruitment centre — a form of protest used dozens of times across Russia in 2022. He fled to Kyrgyzstan, was kidnapped, presumably by the Russian security forces, and returned to Russia for trial. Ruslan Siddiqi (chapter 10), a Russian and Italian citizen, derailed a train carrying munitions to the Ukrainian front. He has been sentenced to 29 years, and has said that he can be seen as a “partisan”, and “classified as a prisoner of war”, rather than a political prisoner.

The fourth group of protagonists, jailed for what they said rather than anything they did, have records of activism for social justice and democratic rights stretching back decades: Alexei Gorinov (chapter 1), a municipal councillor in Moscow who dared to refer to Russia’s war as a “war” in public; Mikhail Kriger, an outspoken opponent of Russia’s war on Ukraine since 2014 (chapter 4); Andrei Trofimov (chapter 5); and Aleksandr Skobov (chapter 7), who was first jailed for political dissent in 1978, in the Soviet Union, and who 47 years later in 2025 told the court: “Death to the Russian fascist invaders! Glory to Ukraine!”

Two activists prosecuted for anti-war action, who made their statements outside court, are featured in chapters 11 and 12. Kirill Butylin (chapter 11) was the first person arrested for firebombing a military recruitment office, in March 2022. No record of his court appearance is available, but his defiant message on social media is: “I will not go to kill my brothers!” Savelii Morozov (chapter 12) was fined for denouncing the war to a military recruitment commission in Stavropol, when applying to do alternative (non-military) service.

The ten anti-war speeches in court recorded in this book are by no means the only ones. Another 17 are summarised in chapter 13. These speeches, along with others by defendants who railed against the annihilation of free speech, or protested against grotesque frame-ups, have been collected and published by the “Poslednee Slovo” (“Last Word”) website.

High-profile Russian politicians jailed for standing up to the Kremlin also made anti-war speeches in court, including Ilya Yashin of the People’s Freedom Party, sentenced to eight-and-a-half years in December 2022 for denouncing the massacres of Ukrainian civilians at Bucha and Irpin, and Vladimir Kara-Murza, sentenced in April 2023 to 25 years for treason. Both of them were freed, along with Sasha Skochilenko, in the prisoner exchange of August 2024. Other prominent political figures remain in detention for opposing the war, including Boris Kagarlitsky, a sociologist and Marxist writer, sentenced in February 2024 to five years for “justifying terrorism”, and Grigory Melkonyants, co-chair of the Golos election monitoring group, sentenced in May 2025 to five years for working with an “undesirable organisation”. Dozens of journalists and bloggers are behind bars too.

These better-known, politically motivated people are only a fraction of the thousands persecuted by the Kremlin. The cases recorded by human rights organisations include thousands of Ukrainians detained in the occupied territories. In many cases their fate, and whereabouts, is unknown: they may be dead or imprisoned. Thousands more Russians who have spoken out against the war, or been caught in the merciless dragnet by accident, are behind bars. So are “railway partisans” who sabotaged military supply trains, and others who denounced their regime’s support for Putin’s war, in Belarus. In Chapter 14, we outline the resistance to the Kremlin’s war, the repression mobilised in response to it, and the scale of the twenty-first-century gulag that has been brought into being. Notes, giving sources for all the material in the book, are at the end.

People resisting injustice have for centuries, in many countries, made use of the courts as a public platform. Irish rebels against British colonial violence began doing so at the end of the eighteenth century. In Russia, the tradition goes back at least to the 1870s, when Narodniki (Populists), speaking to judges trying them for violent protests, denounced the autocratic dictatorship. The workers’ movements that culminated in the 1917 revolutions used courtroom propaganda widely. When Stalinist repression reached its peak in the 1930s, the major purge trials were designed to eliminate it: their format was prearranged, with abject, false confessions. The practice reappeared after the post-Stalinist “thaw”, in the 1965 trial of the dissident writers Andrei Siniavsky and Yulii Daniel.

Courtroom speeches have again become a powerful weapon under Putin — and the Kremlin dictatorship is finding ways to get its revenge. It added three years to Andrei Trofimov’s sentence (chapter 5) — for the fantastical, false “offences” of disseminating false information about the army and “condoning terrorism” — based solely on what he said at his first trial. Other anti-war prisoners, including Alexei Gorinov (chapter 1) have had years added on to their sentences, on the basis of false “evidence” provided by prison officers, or prisoners terrorised by those officers.

Why did they do it? Why did our protagonists make protests that carried the risk of many years in the hell of the Russian prison system? Why, when brought to court, did they choose to make these statements that carried further risk? They have weighed their words and spoken for themselves; no attempt will be made here to summarise. However it is noteworthy that all of them addressed their speeches to their fellow citizens, not to the government.

Andrei Trofimov told the court in his second trial that “Ukraine is my audience”, because “Russian society is dead and it is useless to try to talk to it” — but nevertheless went to extraordinary lengths to make sure that his short, sharp message from his first trial, ending “Putin is a dickhead”, was widely circulated in Russian media.

The others had greater hopes in Russian society, including the Ukrainian Bohdan Ziza, who, in the video for which he was jailed, underlined that: “I address myself, above all, to Crimeans and Russians.” In court he said his action was “a cry from the heart” to “those who were and are afraid — just as I was afraid” to speak out, but who did not want the war.

Alexei Rozhkov had no doubt that “millions of my fellow citizens, women and men, young and old, take an anti-war position”, but were deprived of any means to express it. Kirill Butylin appealed to others to make similar protests so that “Ukrainians will know, that people in Russia are fighting for them — that not everyone is scared and not everyone is indifferent.” As for the government, “let those fuckers know that their own people hate them”.

Aleksandr Skobov, now 67 and in failing health, explicitly addressed younger generations. In an open letter from jail, he recalled how as a socialist he had been a “black sheep” among Soviet-era dissidents, most of whom had now passed away. “The blows are falling on other people, most of them much younger.” While “sceptical about ‘pompous declarations about the passing-on of traditions and experience’”, nevertheless, “I want the young people who are taking the blows now to know: those few remaining Soviet dissidents stood side-by-side with them, have stayed with them and shared their journey.”

Given this unity of purpose, of seeking however unsuccessfully to connect with the population at large, we might see the protagonists as practising the “propaganda of the deed” — not in the sense that phrase was given in the early twentieth century by politicians and policemen, as acts of violence, but in its original, broader sense: as any action, violent or not, that stirred one’s fellow citizens to a just cause. For, while some of those whose words are in this book used violence against property, and some specifically justified Ukrainian military violence against Russian aggression, none used violence against people.

Here are two further observations. First: while all the anti-war resisters shared a common purpose, they started with a diverse range of world views. A profound moral sense of duty runs through some of their statements. “Do I regret what has happened?” Igor Paskar asked his judges. “Yes, perhaps I’d wanted my life to turn out differently — but I acted according to my conscience, and my conscience remains clear.” Or, as Alexei Rozhkov put it: “I have a conscience, and I preferred to hold on to it.” Andrei Trofimov, in a similar vein, said at his second trial that “writ large, it is a matter of self-preservation” — not “the preservation of the body per se, of its physical health” but the preservation of conscience in this difficult situation, “my ability to tell black from white, and lies from truth, and, quite importantly, my ability to say out loud what I believe to be true”.

Ruslan Siddiqi voiced his motivation differently, in terms of political ideas about changing society. In letters to Mediazona, an opposition media outlet, he described his path towards anarchism. Expressing dislike for the “rigidity” of some anarchists and communists, he nevertheless envisaged a transition “from a totalitarian state to other forms of government with greater freedoms and further evolution into communities with self-government”. The invasion of Ukraine changed things: anyone who opposed it was declared a traitor by the government. “In such a situation, it is not surprising that some would prefer to leave the country, whereas others would take up explosives. Realising that the war was going to be a long one, at the end of 2022 I decided to act militarily.”

By contrast, Alexei Gorinov founded his defence on pacifist principles, and quoted Lev Tolstoy on the “madness and criminality of war”. Being tried “for my opinion that we need to seek an end to the war”, he could “only say that violence and aggression breed nothing but reciprocal violence. This is the true cause of our troubles, our suffering, our senseless sacrifices, the destruction of civilian and industrial infrastructure and our homes.” Sasha Skochilenko was still more explicit: “Yes, I am a pacifist” she told the court. Pacifists “believe life to be the highest value of all”; they “believe that every conflict can be resolved by peaceful means. I can’t kill even a spider — I am scared to imagine that it is possible to take someone’s life. […] Wars don’t end thanks to warriors — they end thanks to pacifists. And when you imprison pacifists, you move the long-awaited day of the peace further away.”

Savelii Morozov told the military recruitment commission that he would not refuse to fight in all wars, but in this particular, unjust war. A war in defence of one’s homeland could be justified, but not the “crime” being perpetrated in Ukraine.

For Darya Kozyreva, the central issue is Ukraine’s right to self-determination, asserted by force of arms. The war is a “criminal intrusion on Ukraine’s sovereignty”, she told the court. While identifying herself in an interview as a Russian patriot — “a patriot in the real sense, not in the sense that the propagandists give that word” — Kozyreva justified Ukrainian military resistance. Ukraine does not need a “big brother”; it will fight anyone who tries to invade, she said. In Russia, even some of Putin’s political opponents “do not always realise that Ukraine, having paid for its sovereignty in blood, will determine its own future”. She wants to believe in “a beautiful future where Russia lets go of all imperial ambition”.

Aleksandr Skobov expressed the hope that Russia will be defeated militarily in still more categorical terms. He spelled out in court three principles of his political organisation, the Free Russia Forum: the “unconditional return to Ukraine of all its internationally recognised territories occupied by Russia, including Crimea”; support for all those fighting for this goal, including Russian citizens who joined the Ukrainian armed forces; and support for “any form of war against Putin’s tyranny inside Russia, including armed resistance”, but excluding “disgusting” terrorist attacks on civilians.

Second: these anti-war speeches have much to tell us not only about Russia and Ukraine, but about the increasingly dangerous world we live in, in which Putin’s slide to authoritarianism has been succeeded by right-wing, authoritarian turns in the USA and some European countries. Russia’s imperial war of aggression has been followed by Israel’s genocidal offensive in Gaza, in which multiple war crimes — mass murder of civilians, the use of starvation as a weapon, deliberate blocking of aid, and the targeting of journalists, aid workers and international agencies — have been facilitated by the same Western powers that offer lip service to Ukraine’s national rights.

The two aggressor nations, Israel and Russia, aligned with different geopolitical camps, are subject to analogous driving forces. Nationalist ideology supercedes rational economic management; expansionist violence supercedes democracy; the decline of Western neo-liberal hegemony paves the way for militarist thuggery. Capital’s need for social control underpins near-fascist methods of rule. Readers may recognise, in the Russian state’s dystopian efforts of 2022-23 to punish its dissenting citizens as “terrorists” and “traitors”, patterns that are retraced in the unhinged witch-hunts of 2024-25 in the USA and western Europe, against opponents of the Gaza slaughter.

The powers on both sides of the geopolitical divide are frightened of similar things: the defiance and resilience of the opponents of Putin’s war, and the anger that has brought millions of people on to the streets of north American and European cities, in protest at the Gaza genocide. They are frightened of beliefs that are taking shape, in varying forms, that humanity can and should strive for a better, richer life than that offered by the warmongers and dictators. Some of these beliefs are expressed in the chapters of this book.

Robert Davis

October 19, 2025

FILE PHOTO: U.S. President Donald Trump shakes hand with Russian President Vladimir Putin, as they meet to negotiate for an end to the war in Ukraine, at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Anchorage, Alaska, U.S., August 15, 2025. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

A foreign analyst slammed a proposed tunnel project that could link the United States and Russia on Sunday, saying the proposed project "stretches the imagination to the breaking point."

On Friday, Reuters reported that Russian President Vladimir Putin's international investment envoy, Kirill Dmitriev, had proposed building an underground tunnel linking the U.S. and Russia. Dmitriev added that President Donald Trump's ally, Elon Musk and The Boring Company, could help facilitate the construction.

Dmitriev shared more details on his personal X account.

"@elonmusk, imagine connecting the US and Russia, the Americas and the Afro-Eurasia with the Putin-Trump Tunnel - a 70-mile link symbolizing unity. Traditional costs are $65B+, but @boringcompany's tech could reduce it to <$8B. Let's build a future together!" he posted.

Former Moscow Times journalist Charles Hecker slammed the idea during a new interview with Times Radio.

"It's [Dmitriev's] job to dangle really tantalizing business proposals in front of President Trump and in front of the American business community and say 'Look at all of the things that could be accomplished if the war would only come to an end,'" Hecker said. "That's an enormous 'if' at this point."

"This sort of project is beyond anybody's imagination," he continued.

He added that the project could face steep opposition from business owners in Russia.

"There are some Russian businesses that are saying, 'Look, all of these folks left when the going got tough. We don't want them back anymore,'" he said, referring to businesses that left Russia after the country invaded Ukraine. "We're doing this on our own. We're doing it without them. We have China. We have India. We have lots of other partners to do business with. We don't need the Americans."

No comments:

Post a Comment