January 14, 2020

As tensions have ratcheted up between the United States and Iran, a series of tweets by President Donald Trump threatening the deliberate targeting of Iranian cultural sites triggered a strong negative reaction around the world.

In fact, following Trump’s tweets, Pentagon officials reassured the world that the U.S. would not target Iran’s cultural sites, and would follow the laws of armed conflict.

Quickly, the president himself appeared to backtrack, declaring: “You know what, if that’s what the law is, I like to obey the law.”

Explaining his earlier position, Trump had embraced a dangerous logic:

“[Iran is] allowed to kill our people. They’re allowed to torture and maim our people. They’re allowed to use roadside bombs and blow up our people. And we’re not allowed to touch their cultural sites? It doesn’t work that way.”

The argument is disingenuous, as it purports to highlight the value of human life as higher than that of cultural sites, while suggesting that those who want to protect heritage are implicitly attaching more importance to culture than to the torturing and maiming of people. This is simply not true.

Both international law and the U.S. military Law of War manual are clear on why protecting cultural sites in conflicts should be a priority for the belligerents.

A view of Iran’s UNESCO world heritage site of the Qara Kelisa

(Black Church), in Chaldran, 850 kilometres northwest of the

Iranian capital Tehran. Also known as St. Thaddeus Church,

it is believed to have been built in AD 66. AP Photo/Hasan Sarbakhshian

As tensions have ratcheted up between the United States and Iran, a series of tweets by President Donald Trump threatening the deliberate targeting of Iranian cultural sites triggered a strong negative reaction around the world.

In fact, following Trump’s tweets, Pentagon officials reassured the world that the U.S. would not target Iran’s cultural sites, and would follow the laws of armed conflict.

Quickly, the president himself appeared to backtrack, declaring: “You know what, if that’s what the law is, I like to obey the law.”

Explaining his earlier position, Trump had embraced a dangerous logic:

“[Iran is] allowed to kill our people. They’re allowed to torture and maim our people. They’re allowed to use roadside bombs and blow up our people. And we’re not allowed to touch their cultural sites? It doesn’t work that way.”

The argument is disingenuous, as it purports to highlight the value of human life as higher than that of cultural sites, while suggesting that those who want to protect heritage are implicitly attaching more importance to culture than to the torturing and maiming of people. This is simply not true.

Both international law and the U.S. military Law of War manual are clear on why protecting cultural sites in conflicts should be a priority for the belligerents.

A view of Iran’s UNESCO world heritage site of the Qara Kelisa

(Black Church), in Chaldran, 850 kilometres northwest of the

Iranian capital Tehran. Also known as St. Thaddeus Church,

it is believed to have been built in AD 66. AP Photo/Hasan Sarbakhshian

‘Law of War’

In 1954, the Hague Convention tackled the issue of “Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.” The convention established cultural property as a legal category in international law where cultural property was defined as “movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people.”

The convention addresses wartime behaviour by prohibiting the use of cultural property in manners that could lead to its destruction or damage, and establishing the obligation to refrain from any act of hostilities directed at cultural property except in “cases of unavoidable military necessity.”

Furthermore, countries are forbidden from using their own cultural sites for military purposes (such as storing weapons or explosives) in hopes that they will be protected from an attack.

The Hague Convention was very much a reaction to the devastation brought about by the Second World War, which saw the deliberate destruction of countless cultural treasures. It signalled a desire on the part of the international community to protect the world’s cultural heritage from the ravages of war, and recognition that the loss of this heritage represents a loss for the country affected as well as for humanity.

What is cultural heritage important?

More recently, the world has witnessed the wanton destruction and plundering of historical heritage driven by ideological motives in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Cambodia, Mali, Syria and in many other countries rich in archeological heritage.

These events have highlighted how the destruction of cultural heritage can become just another weapon of war, one with targets that aren’t military resources or infrastructure, but rather the memories, history and identity of a people.

Left: Temple of Bel in April 2010, Palmyra, Syria.

Right: ISIL propaganda image showing the temple’s

destruction in 2015. (Left: Bernard Gagnon; right: ISIL propaganda),

CC BY

Indeed, often the deliberate performative destruction of cultural heritage is used exactly for that purpose: erasing traces of a past that someone wants forgotten, so that a new history can be written.

Examples of this abound, from the Taliban’s demolition of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan to the destruction of the Timbuktu manuscripts in Mali at the hand of the Islamist rebels of Andar Dine and the annihilation of Shi’a and Sufi heritage by ISIS in its controlled territory.

Teaching military cultural awareness

Awareness of the importance of preserving cultural sites in war, both to protect the world’s cultural heritage and to signal respect of every country’s history and contribution to humankind, is incorporated in the training received by the United States’ armed forces. The Department of Defense’s Law of War manual includes literally hundreds of references to this issue.

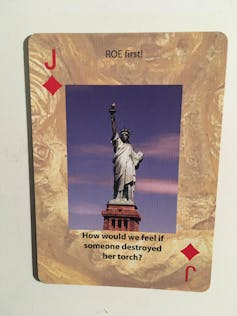

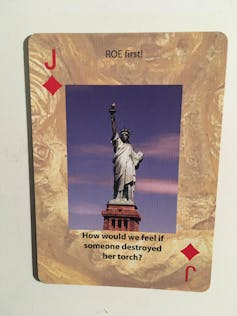

The Pentagon deck of cards, ‘Respect Afghan Heritage,’ was handed out to troops with hopes of raising cultural awareness. (@hannahbloch)

The Pentagon even distributed decks of playing cards with photos of cultural sites to troops serving in Iraq and Afghanistan to underscore the need to safeguard heritage sites and artifacts. One of the cards showed a picture of the Statue of Liberty, with the words, “How would we feel if someone destroyed her torch?”

At times of heightened tensions, when relations between two or more countries veer dangerously towards conflict and countless lives are at stakes, it is worth remembering why culture matters not only in peacetime but also, or perhaps especially, in conflict, when humanity is most at risk of getting lost in the fog of war.

In 1954, the Hague Convention tackled the issue of “Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.” The convention established cultural property as a legal category in international law where cultural property was defined as “movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people.”

The convention addresses wartime behaviour by prohibiting the use of cultural property in manners that could lead to its destruction or damage, and establishing the obligation to refrain from any act of hostilities directed at cultural property except in “cases of unavoidable military necessity.”

Furthermore, countries are forbidden from using their own cultural sites for military purposes (such as storing weapons or explosives) in hopes that they will be protected from an attack.

The Hague Convention was very much a reaction to the devastation brought about by the Second World War, which saw the deliberate destruction of countless cultural treasures. It signalled a desire on the part of the international community to protect the world’s cultural heritage from the ravages of war, and recognition that the loss of this heritage represents a loss for the country affected as well as for humanity.

What is cultural heritage important?

More recently, the world has witnessed the wanton destruction and plundering of historical heritage driven by ideological motives in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Cambodia, Mali, Syria and in many other countries rich in archeological heritage.

These events have highlighted how the destruction of cultural heritage can become just another weapon of war, one with targets that aren’t military resources or infrastructure, but rather the memories, history and identity of a people.

Left: Temple of Bel in April 2010, Palmyra, Syria.

Right: ISIL propaganda image showing the temple’s

destruction in 2015. (Left: Bernard Gagnon; right: ISIL propaganda),

CC BY

Indeed, often the deliberate performative destruction of cultural heritage is used exactly for that purpose: erasing traces of a past that someone wants forgotten, so that a new history can be written.

Examples of this abound, from the Taliban’s demolition of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan to the destruction of the Timbuktu manuscripts in Mali at the hand of the Islamist rebels of Andar Dine and the annihilation of Shi’a and Sufi heritage by ISIS in its controlled territory.

Teaching military cultural awareness

Awareness of the importance of preserving cultural sites in war, both to protect the world’s cultural heritage and to signal respect of every country’s history and contribution to humankind, is incorporated in the training received by the United States’ armed forces. The Department of Defense’s Law of War manual includes literally hundreds of references to this issue.

The Pentagon deck of cards, ‘Respect Afghan Heritage,’ was handed out to troops with hopes of raising cultural awareness. (@hannahbloch)

The Pentagon even distributed decks of playing cards with photos of cultural sites to troops serving in Iraq and Afghanistan to underscore the need to safeguard heritage sites and artifacts. One of the cards showed a picture of the Statue of Liberty, with the words, “How would we feel if someone destroyed her torch?”

At times of heightened tensions, when relations between two or more countries veer dangerously towards conflict and countless lives are at stakes, it is worth remembering why culture matters not only in peacetime but also, or perhaps especially, in conflict, when humanity is most at risk of getting lost in the fog of war.

Costanza Musu

Associate Professor, Graduate Scool of Public and International Affairs, University of Ottawa, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

Disclosure statement

Costanza Musu receives funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council.

Partners

University of Ottawa provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

Associate Professor, Graduate Scool of Public and International Affairs, University of Ottawa, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

Disclosure statement

Costanza Musu receives funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council.

Partners

University of Ottawa provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.