Is the defence department's crackdown on leaks about security — or avoiding embarrassment?

Murray Brewster 6 hrs ago

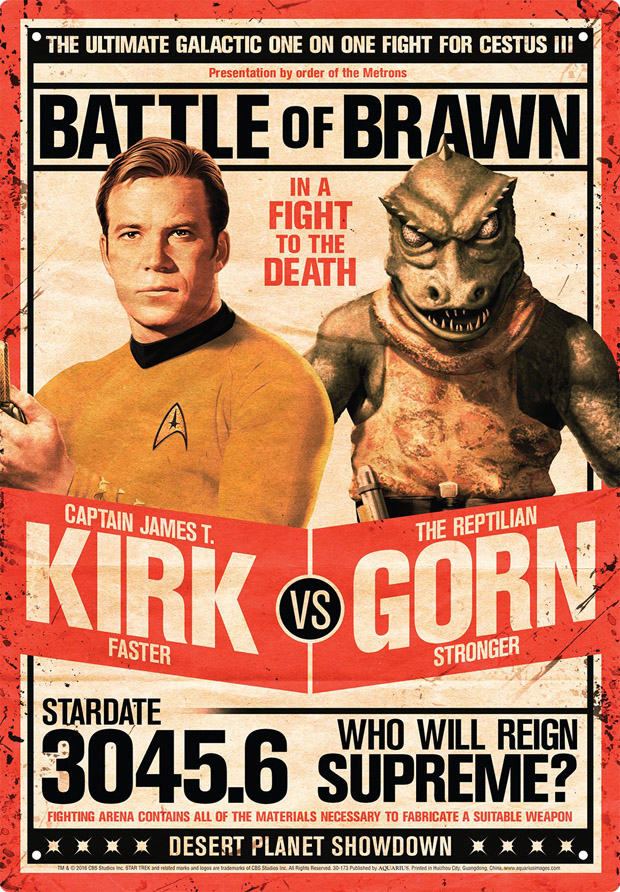

© Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press Vice Admiral Mark Norman arrives at the Ottawa courthouse with lawyer Marie Henein on Wednesday, May 8, 2019. The collapse of the case against Norman proved to be a public embarrassment for the Trudeau government.

A former Conservative defence minister — now premier of Alberta — once said that if leaking government information was a criminal offence, half of the people at National Defence Headquarters would be up on charges.

Jason Kenney's wry appraisal of the Department of National Defence leaking "like a sieve" distills a widely-held belief in Ottawa.

His observation was delivered last year at the conclusion of the criminal case against retired vice-admiral Mark Norman, the former second-in-command of the military, who was accused of leaking cabinet secrets to a Quebec shipyard executive and a now-former CBC reporter.

What the case exposed through the exhaustive, months-long pretrial process was the complicated, contradictory and sometimes incoherent approach of the defence department and the federal government writ large to the question of what actually constitutes a "secret".

Whose secrets?

Some secrets are obvious — others not so much.

Which explains why the defence establishment has embarked upon the creation of new directives that will crack down on the handling of unclassified information.

Postmedia first published word of the revamp earlier this week, linking it with recent leaks to CBC News (over the crash of an air force Cyclone helicopter) and Global News (over the horrifying conditions facing troops supporting long-term care homes).

The military's current deputy commander, Lt.-Gen. Jean-Marc Lanthier, said that the process of revising the Defence Administrative Orders and Directives (DAOD) actually began last summer.

That would have been only weeks after the conclusion of the case against Norman — timing that some experts see as both significant and suspicious.

'An uncomfortable coincidence'

"It's a coincidence ... an uncomfortable coincidence that the DAOD was starting to be drafted at the same time there was a climax to the Norman affair," said retired lieutenant-colonel Rory Fowler, a former military lawyer now in private practice.

Much, he said, will depend upon what ends up in the regulations, which are still in draft form and still under consideration.

Depending on which side of the fence they were on during the former naval commader's legal saga, there's still a belief abroad in some political circles that Norman got away with leaking — and that the Crown couldn't make the case because the information, while sensitive, likely did not fit the strict definition of a secret.

'If they want to leak, they'll leak'

Lanthier denied there was a link between the high-profile case and the new regulations, which will include penalties.

"From my perspective, that is not what it was about," the vice chief of the defence staff told CBC News. "The DAOD is not about clamping down on people, punishing people or going after people.

"Folks are savvy. If they want to leak, they'll leak."

He claimed that the new regulations are not a "prohibitive policy, but an enabling policy" that will give both military and civilian members guidance on the proper handling of information for security and business reasons.

Unclassified information will be put through an "injury test" to decide whether it should be released into the public domain, Lanthier said.

Chris Waddell, a journalism professor at Carleton University, said he's baffled by that statement.

A clash of narratives

"The problem with that is, what do you mean by 'injury' and to whom?" said Waddell. "Does injury mean embarrassment? Does it mean it's just stuff we don't want people to know? I don't think that's a good enough reason."

One of the focal points of Norman's prosecution was the notion that the alleged leak of a cabinet decision to pause a $668 million shipbuilding program was an embarrassment to the Liberal government.

Waddell said it's possible the Trudeau government and the department were humiliated to see their narratives contradicted by leaks (on the helicopter crash in particular) — and suggested that could be the motive behind the regulation revision.

"Their initial handling of the helicopter crash was disingenuous," he said, referring to early reports that the CH-148 Cyclone had simply disappeared from contact — when in fact it had crashed within sight of HMCS Fredericton. "The families have every right to know before anyone else, but the Canadian public also has a right to full disclosure."

Operational security

Waddell said it could be argued that the defence department is now trying to give itself the same power at home the military has overseas — when it invokes operational security (OPSEC) to safeguard information during missions.

Lanthier denied that politics would play a role in the new regulations; the military, he said, is "apolitical."

But he acknowledged that one of the considerations informing the review will be whether leaks of "information, even though unclassified" might "impede the department's ability to formulate adequate advice to the government."

That was one of the arguments underpinning the Crown's case against Norman — that the leak of shipbuilding information interfered with cabinet's decision-making process.

The impending regulations are not the only new front in the information war. The defence department makes frequent use of non-disclosure agreements to keep information under wraps and silence critics. Those efforts sometimes reach the level of the absurd.

'A degree of incompetence'

Last year, when Norman's case was settled, the department said it could not disclose whether the former top commander had signed a non-disclosure agreement.

Similarly, when asked last week whether Norman and former Canadian Forces ombudsman Gary Walbourne, who was forced into early retirement, had signed gag orders, the department said it could not comment on privacy matters.

Another avenue of disclosure for government information — the Access To Information and Privacy (ATIP) system — is a shambles and plagued by long delays, according to its many critics. Fowler said he has waited for very long periods of time to get answers to his own ATIP requests — three years, in one case.

"In my view, it's not just an intention to withhold the information. There's a degree of incompetence," he said, adding that some ATIP coordinators don't know where to look for the records requested.

The Department of National Defence has insisted its new directives on handling unclassified information will not limit "a DND employee's or CAF member's ability to report wrongdoing."

That may be so, but it's cold comfort for previous whistleblowers — some of whom have faced retribution for speaking up, both internally and publicly.

Former sub-lieutenant Laura Nash — who was once told to choose between her career and her child — said many who try to report wrongdoing in the military are ostracized and belittled.

"There was no incentive for members of the military to do what was right, and every incentive for people in the military to side with the person who is doing wrong," she said, adding it's tough to report someone who outranks you and holds your career in their hands.

Nash's lawyer, Natalie MacDonald, said she believes there should be specific whistleblower protection for military members written into legislation, above and beyond what already exists in the federal public service

© Valeria Cori-Manocchio/CBC Parc Extension resident Mohammad Suleman (right) has been issued an eviction notice for the apartment he has been living in for 15 years. In two weeks, the province's rental board will begin to enforce decisions made earlier this…

© Valeria Cori-Manocchio/CBC Parc Extension resident Mohammad Suleman (right) has been issued an eviction notice for the apartment he has been living in for 15 years. In two weeks, the province's rental board will begin to enforce decisions made earlier this…