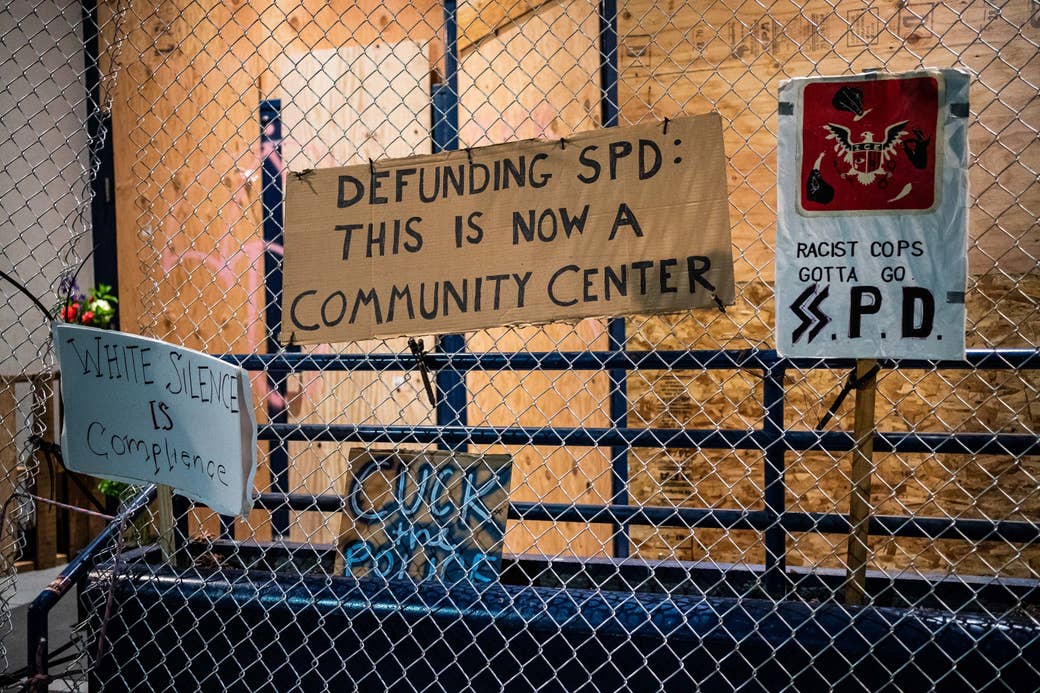

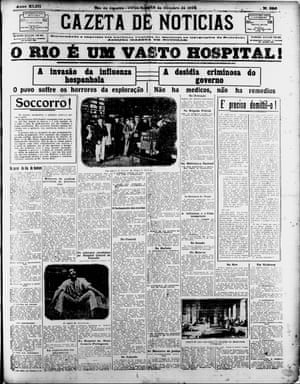

'All lies': how the US military covered up gunning down two journalists in Iraq Dean Yates, a former Reuters employee now based in northern Tasmania.

Dean was bureau chief in Baghdad when two of his colleagues, Saeed Chmagh and Namir Noor-Eldeen, were killed by the US military. Photograph: Matthew Newton/The Guardian

Former Reuters journalist Dean Yates was in charge of the bureau in Baghdad when his Iraqi colleagues Namir Noor-Eldeen and Saeed Chmagh were killed. A WikiLeaks video called Collateral Murder later revealed details of their death

by Paul Daley THE GUARDIAN Sun 14 Jun 2020

For all the countless words from the United States military about its killing of the Iraqi Reuters journalists Namir Noor-Eldeen and Saeed Chmagh, their colleague Dean Yates has two of his own: “All lies.”

The former Reuters Baghdad bureau chief has also inked some on his arm – a permanent declaration of how those lies “fucked me up”, while he blamed first Namir – unfairly – and then himself for the killings.

The tattoo on his left shoulder features a looped green ribbon bearing the words Iraq, Bali and Aceh. At opposite points of the ribbon is etched PTSD and Fight Back, Moral injury and July 12 2007.

Yates’s experiences covering the 2002 Bali bombings and the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004 seeded his post-traumatic stress, but 12 July 2007 is the day that changed his life irrevocably – while violently ending Namir’s and Saeed’s. It’s also the day that linked him by a thread of truth to the WikiLeaks co-founder Julian Assange, who would, three years later, become the world’s most infamous hacker-publisher-activist with his release of thousands of classified US military secrets.

Reuters photographer Namir Noor-Eldeen was 22 when he was killed in Baghdad on 12 July 2007. Photograph: Khalid Mohammed/AP

Reuters photographer Namir Noor-Eldeen was 22 when he was killed in Baghdad on 12 July 2007. Photograph: Khalid Mohammed/AP

They included a video WikiLeaks titled Collateral Murder, filmed from a US military Apache helicopter as it blasted to pieces Namir, 22, and Saeed, 40, and nine other men, while seriously wounding two children.

The US continues its legal efforts to extradite Assange from a British prison, where he is remanded in failing health, to face espionage allegations. Instructively, the detailed, 37-page US indictment against him makes no mention of Collateral Murder – the video that caused the US government and military more reputational damage than all the other secret documents combined, and that launched WikiLeaks and Assange as the foremost global enemy of state secrecy.

The US continues its legal efforts to extradite WikiLeaks co-founder Julian Assange from a British prison. Photograph: Matt Dunham/AP

Is the US concerned that referring to the video will give rise to war crimes charges against the military personnel involved in the attack? Certainly, bringing the video into the prosecution case against Assange could only vindicate his role in exposing the US military’s lies about the ghastly killings.

‘Loud wailing broke out’

Early on 12 July 2007 Yates sat in the “slot desk” in the Reuters office in Baghdad’s red zone. He was ready for the usual: a car bomb attack while Iraqis headed to work, a militant strike on a market, the police or the Iraqi military. It was quieter than usual.

Press freedom is at risk if we allow Julian Assange's extradition

Roy Greenslade

Yates recalls: “Loud wailing broke out near the back of our office … I still remember the anguished face of the Iraqi colleague who burst through the door. Another colleague translated: ‘Namir and Saeed have been killed.’”

Reuters staff drove to the al-Amin neighbourhood where Namir had told colleagues he was going to check out a possible US dawn airstrike. Witnesses said Namir, a photographer, and Saeed, a driver/fixer, had been killed by US forces, possibly in an airstrike during a clash with militants.

Dean Yates is now based in northern Tasmania. He says Assange brought the truth of the killings to the world. Photograph: Matthew Newton/The Guardian

Yates emailed the US military spokesman in Iraq and telephoned a senior Reuters editor to tell him the news.

While the bureau was in a crisis of anger and mourning, Yates still had to write the early stories about the two men killed on his watch. He initially wrote that they had died in what Iraqi police called “American military action”.

Yates says: “Pictures taken by our photographers and camera operators showed a minivan at the scene, its front mangled by a powerful concussive force … There was much we didn’t know. US soldiers had seized Namir’s two cameras, so we couldn’t check what he’d been photographing.”

By early evening the military spokesman still had not replied. Yates pressed him for a response– and for the return of Namir’s cameras. Just after midnight, the US military released a statement headlined: “Firefight in New Baghdad. US, Iraqi forces kill 9 insurgents, detain 13.”

It quoted a US lieutenant as saying: “Nine insurgents were killed in the ensuing firefight. One insurgent was wounded and two civilians were killed during the firefight. The two civilians were reported as employees for the Reuters news service. There is no question that Coalition Forces were clearly engaged in combat operations against a hostile force.”

Yates, shaking his head, says: “The US assertions that Namir and Saeed were killed during a firefight was all lies. But I didn’t know that at the time, so I updated my story to take in the US military’s statement.”

Dean Yates says news organisations dealt with the US military in good faith: ‘What a joke that turned out to be.’ Photograph: Matthew Newton/The Guardian

It was a shocking time for locally engaged staff of foreign news organisations in Baghdad. On 13 July, the day of Namir and Saeed’s funerals, Khalid Hassan, a New York Times reporter/translator, was shot dead.

After the funerals Yates pressed the US military for Namir’s cameras and for access to cameras and air-to-ground recordings involving the Apache that killed his colleagues.

On 14 July, Yates learned that militants had murdered a Reuters Iraqi text translator.

In an effort to save employees’ lives, he began collaborating with other foreign news organisation managers to engage with the US military to better understand its rules of engagement.

“We dealt with them in good faith,” he says. “What a joke that turned out to be.”

‘Cold-blooded murder’

On 15 July the US military returned Namir’s cameras. Namir had photographed the aftermath of an earlier shooting and, a few minutes later (just before his death), US military Humvees at a nearby crossroads. There were no frames of insurgent gunmen or clashes with US forces. Date and time stamps show that three hours after Namir died his camera photographed a US soldier in a barrack or tent. The troops who mopped up the killing scene evidently messed around with his cameras afterwards.

Date and time stamps show that three hours after Namir Noor-Eldeen died his camera was used to photograph a US soldier. Photograph: Reuters

Reuters staff had by now spoken to 14 witnesses in al-Amin. All of them said they were unaware of any firefight that might have prompted the helicopter strike.

Yates recalls: “The words that kept forming on my lips were ‘cold-blooded murder’.”

The Iraqi staff at Reuters, meanwhile, were concerned that the bureau was too soft on the US military. “But I could only write what we could establish and the US military was insisting Saeed and Namir were killed during a clash,” Yates says.

The meeting that put him on a path of destructive, paralysing – eventually suicidal – guilt and blame “that basically fucked me up for the next 10 years”, leaving him in a state of “moral injury”, happened at US military headquarters in the Green Zone on 25 July.

Yates and a Reuters colleague met the two US generals who had overseen the investigation into the killings of Namir and Saeed.

Dean Yates’ framed photos of his colleagues. ‘The words that kept forming on my lips were “cold-blooded murder”.’ Photograph: Dean Yates

It was a long, off-the-record meeting. The generals revealed a mass of detail, telling them a US battalion had been seeking militias responsible for roadside bombs. They had called in helicopter support after coming under fire. One Apache had the call sign Crazy Horse 1-8.

“They described a group of men spotted by this Apache,” Yates says. “Some appeared to be armed and Crazy Horse 1-8 … had requested permission to fire because we were told these men were ‘military-aged males’ … and they appeared to have weapons and they were acting suspiciously. So, we were told those men on the ground were then ‘engaged’.”

The generals showed them photographs of what was collected after the shooting, including “a couple of AK-47s [assault rifles], an RPG [rocket-propelled grenade] launcher and two cameras”.

“I have wondered for many years how much of that meeting was carefully choreographed so we would go away with a certain impression of what happened. Well, for a time it worked,” Yates says.

There was some discussion about what permitted Crazy Horse 1-8 to open fire if there was no firefight. One of the generals insisted the dead were of “military age” and, because apparently armed, were therefore “expressing hostile intent”.

Yates says: “Then they said, ‘OK, we are just going to show you a little bit of footage from the camera of Crazy Horse 1-8.’”

The generals showed them about three minutes of video, beginning with a group including Saeed and Namir on the street.

Saeed Chmagh and Namir Noor-Eldeen in the Collateral Murder video. Photograph: WikiLeaks

“We heard the pilot seek permission from the ground to attack.” After the pilot receives permission, the men are obscured. The chopper circles for a clear aim.

'As I watch the footage, anger calcifies in my heart'

Read more

Yates says: “When the chopper circled around, Namir can be seen going to a corner and crouching down holding something – his long-lens camera – and is taking photographs of Humvees. One of the crew says, ‘He’s got an RPG’ … He’s clearly agitated. And then another 15, 20 seconds the crew gets a clear line of sight … I’m watching Namir crouching down with his camera which the pilot thinks is an RPG and they’re about to open fire. I then see a man I believe to be Saeed walking away, talking on the phone. Then cannon fire hits them. I’ve got my head in my hands … The generals stop the tape.”

The generals downplayed a slightly later incident when they said a van had pulled up and Crazy Horse 1-8 assessed it as aiding the insurgents, removing their bodies and weapons.

“At some point after watching that footage it became burnt into my mind that the reason the helicopter opened fire was because Namir was peering around the corner. I came to blame Namir for that attack, thinking that the helicopter fired because he made himself look suspicious and it just erased from my memory the fact that the order to open fire had already been given. They were going to open fire anyway. And the one person who picked this up was Assange. On the day that he released the tape [5 April 2010] he said that helicopter opened fire because it sought permission and was given permission. And he said something like, ‘If that’s based on the rules of engagement then the rules of engagement are wrong.’”

Reuters asked for the entire video. The general refused, saying Reuters had to seek it under freedom of information laws. The agency did so, but its requests were denied.

During the next year, Yates checked when it might be released. All the while he and other executives from foreign news organisations continued their good faith meetings with various US generals to enhance the safety of their Baghdad staff.

Namir Noor-Eldeen, pictured, and Saeed Chmagh would have remained forgotten statistics in a war that killed countless Iraqi combatants, hundreds of thousands of civilians and 4,400-plus US soldiers had it not been for Chelsea Manning. Photograph: Ahmad Al-Rubaye/AFP via Getty Images

On the anniversary of Namir’s and Saeed’s killings, Yates wanted to break the off-the-record agreement with the generals. He argued that enough time had passed for the Pentagon to give Reuters the tape. His superiors insisted the agreement be honoured. A passage in the article he wrote for the anniversary read: “Video from two US Apache helicopters and photographs taken of the scene were shown to Reuters editors in Baghdad on July 25, 2007 in an off-the-record briefing.”

Yates stayed in Baghdad until October 2008. He did not get the full video. Reuters continued to ask for it. Yates was reassigned to Singapore. He displayed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, including noise aversion and emotional numbness. He avoided anything to do with Iraq and had trouble sleeping.

On 5 April 2010, when Wikileaks released Collateral Murder at the National Press Club in Washington, rendering himself and WikiLeaks household names (and exposing how the US prosecuted the Iraq war on the ground), Yates was off the grid,walking in Cradle Mountain national park on a Tasmanian holiday with his wife, Mary, and their children.

Namir and Saeed would have remained forgotten statistics in a war that killed countless Iraqi combatants, hundreds of thousands of civilians and 4,400-plus US soldiers had it not been for Chelsea Manning, a US military intelligence analyst in Baghdad. In February 2010 Manning, then 23, discovered the Crazy Horse 1-8 video and leaked it to WikiLeaks. The previous month Manning had leaked 700,000 classified US military documents about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to WikiLeaks. Assange unveiled the Crazy Horse 1-8 footage (a 17-minute edited version and the full 38-minute version remain on WikiLeaks’ Collateral Murder site). The video was picked up by thousands of news organisations worldwide, sparking global outrage and condemnation of US military tactics in Iraq – and launching WikiLeaks as a controversial truth-teller, publisher and critical enemy of state secrecy. WikiLeaks later made public the cache of 700,000 documents.

‘Look at those dead bastards’

Collateral Murder is distressing viewing. The carnage wrought by the 30mm cannon fire from the Apache helicopter is devastating. The video shows the gunner tracking Namir as he stumbles and tries to hide behind garbage before his body explodes as the rounds strike home.

The words of the crew are sickening.

There is this, after Namir and others are blown apart:

“Look at those dead bastards.”

“Nice.”

And this:

“Good shoot’n.”

“Thank you.”

Saeed survives the first shots. The chopper circles, Saeed in its sights, as he crawls, badly injured and desperate to live.

“Come on buddy … all you got to do is pick up a weapon,” the gunner says, eager to finish Saeed off.

The attack on the van that stopped to help the journalists. Photograph: WikiLeaks

A van pulls up. Two men, including the driver (whose children are in the back), help the dying Saeed get in.

There is more urgent banter in the air about engaging the van. Crazy Horse 1-8 promptly attacks it.

“Oh yeah, look at that. Right through the windshield.”

Two days after Assange released the video, Yates emerged from Cradle Mountain. It was hours before he turned on his phone and checked emails, finally learning of Collateral Murder in a local newspaper.

“I thought, ‘No, this can’t be the same attack … that leads on to all this other stuff that we never knew about’ … This was the full horror – Saeed had been trying to get up for roughly three minutes when this good Samaritan pulls over in this minivan and the Apache just opens fire again and just obliterates them – it was totally traumatising.”

Yates immediately thought: “They [the US military] fucked us. They just fucked us. They lied to us. It was all lies.”

The day Collateral Murder was released, a spokesman for US Central Command said an investigation of the incident shortly after it occurred found that US forces were not aware of the presence of the news staffers and thought they were engaging armed insurgents.

“We regret the loss of innocent life, but this incident was promptly investigated and there was never any attempt to cover up any aspect of this engagement.”

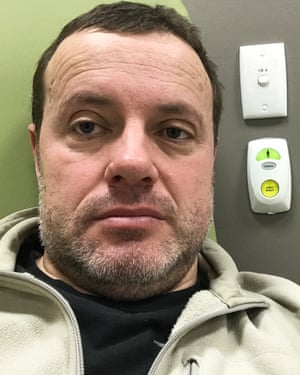

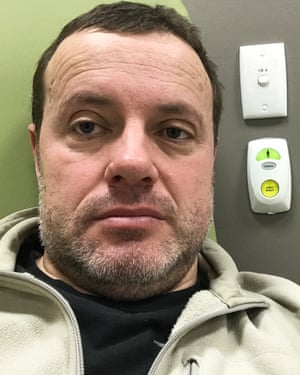

Dean Yates not long after his admission to Ward 17, a PTSD specialist unit. Photograph: Dean Yates

Edited into the story Reuters published about Collateral Murder was that line from Yates’s first anniversary article: “Video from two US Apache helicopters and photographs taken of the scene were shown to Reuters editors in Baghdad on July 25, 2007 in an off-the-record briefing.”

Reuters’ outraged Iraqi staff were under the misapprehension Yates had seen the whole video.

“I hate to admit it, but this was my chance to set the record straight and I didn’t do it,” Yates says. “I just, I don’t know, didn’t have the courage to do it … I should’ve picked up the phone and said to [Reuters] ‘we cannot let this go and we have to say what we knew’.”

In one email to a senior editor that night, Yates wrote: “I think we need to push the issue of transparency strongly with the US military … When I think back to that meeting with two generals in Baghdad … I feel cheated … they were not being honest … We met afterwards with the military several times to work on improving safety for reporters in Iraq.”

The editor replied: “I appreciate how awful this is for you. Take good care; rest assured that we’re not letting this drop.”

Then Yates let it go.

How shameful it is to the military – they know that there’s potential war crimes on that tapeDean Yates

He moved to Tasmania, endured PTSD and eventually, after three inpatient stays at Austin Health’s Ward 17 in Melbourne (a specialist unit for PTSD) grappled with his emotional pain – the “moral injury” now articulated in his shoulder tattoo – over the deaths of Namir and Saeed. Reuters paid for his treatment in Ward 17 and agreed to create the role of head of mental health and wellbeing strategy for him when he could no longer work as a journalist (he has now left the company).

It was in Ward 17, in 2016 and 2017, that he came to understand the moral injury he was enduring by unfairly blaming Namir for making Crazy Horse 1-8 open fire. The other element of his moral injury related to his shame at failing to protect his staff by uncovering the lax rules of engagement in the US military before they were shot – and for not disclosing earlier his understanding of the extent to which the US had lied. Yates made peace with Namir and Saeed – and himself.

Assange, he says, brought the truth of the killings to the world and exposed the lie that he and others had not.

“What he did was 100% an act of truth-telling, exposing to the world what the war in Iraq looks like and how the US military lied.”

The tattoo on Yates’ right shoulder pays tribute to his breakthroughs at Ward 17. Photograph: Matthew Newton/The Guardian

Of the US indictment against Assange, Yates says: “The US knows how embarrassing Collateral Murder is, how shameful it is to the military – they know that there’s potential war crimes on that tape, especially when it comes to the shooting up of the van …They know that the banter between the pilots echoes the sort of language that kids would use on video games.”

Fight Back, read the words inked on to Yates’s left shoulder.

Amid the continuing attempt to extradite Assange to the US, many more words are likely to be spoken about the events of 12 July 2007, the lies of the US military – and their exposure through Collateral Murder.