The well-to-do hate to see them come; the proletarians loathe them for having vamoosed to greener pastures. The Artists deride them, the Intellectuals despise them. The petite bourgeoisie has been the butt of derision for over 200 years. Ambiguity and fluidity are the main characteristics of this conflicted social class. Now, however, the species seems to be dying out. Why does everybody love to hate them? And where have they gone to?

— — —

Lapetite bourgeoise — she has a little bit of capital, she owns a small business, maybe she buys labour on a tiny scale. She has some bits of education.

She might be a London flower-shop owner named Eliza, she might be a young writer by the name of Jo, governessing it in New York while peddling her sensationalist Gothic stories — these girls own (at least partly) their means of production. The successful petite bourgeoise owns a bit of a house, employs two boys, has enough money in the bank to weather the bad times. But it can go either way. Jo inherits Aunt March’s house and starts a school — a transcendentalist school. Eliza Doolittle marries the birdbrained Freddie Eynsford-Hills, and against all odds the shop flourishes (presumably when the couple start to sell asparagus).

She minds her own business, the much-maligned petite bourgeoise. She does mind her business, tooth and claw — it’s the only thing she minds. The unforgettable Mrs Thatcher, who would never let us forget that she was a shopkeeper’s daughter, and the unspeakable Mrs Augusta Elton are prototypical examples of p‘tit-boos who got the petty bourgeoisie its bad reputation.

Ambiguity and fluidity — the petit bourgeois can go either way. What distinguishes the amiable from the despicable specimen? It’s fairly simple: politically, economically, socially and, above all, ethically, the petit bourgeois has choices to make.

Historically, the petty bourgeoisie got a bad press

Even before Marx, we had the abominable Mrs Augusta Elton, she of the £10.000 and the sister who owns a barouche-landau, she of the social vulgarities and the “inner resources”, of the ignorance and the lack of good breeding. This is Emma, frothing at the mouth:

“Insufferable woman!” was her immediate exclamation. “Worse than I had supposed. Absolutely insufferable! Knightley! — I could not have believed it! Knightley! Never seen him in her life before, and call him Knightley! — and discover that he is a gentleman! A little upstart, vulgar being, with her Mr E., and her caro sposo, and her resources, and all her airs of pert pretension and under-bred finery. Actually to discover that Mr Knightley is a gentleman! “Jane Austen, Emma (1815): Chapter 32

Emma, let’s not forget, was still smarting from the Harriet situation, and her description of this extremely offending petite bourgeoise may have been a bit harsh. For all that, she would have little occasion later to soften her opinion — quite the contrary.

Surely Mrs E. and the terrifying Hyacinth Bucket were sisters under the skin.

Surely Mrs E. and the terrifying Hyacinth Bucket were sisters under the skin.

Up till, say, the 1840s, the petite bourgeoisie was a sub-stratum of the middle classes; in most languages, the expression had a neutral meaning. In French, “petit bourgeois” had been the common designation for a member of the urban lower middle classes since the early seventeenth century; it didn’t have any disparaging connotations — except possibly aristocratic disdain. In English, the term lower middle class mainly designated the semi-autonomous peasantry and the urban small merchants; “petty bourgeoisie”, however, is attested from the 1840s, even before Marx used it in the Communist Manifesto. In Russian, too, the word seems to have acquired its negative connotation later, through Marxist usage. In American literature and popular culture, George F. Babbitt (Babbit, 1922) became the archetype of the vacuous, complacent and conformist businessman. The Philistine behaviour of a Babbitt is described by the fabulous word Babbitry. A German “Biedermann”, too, is a conservative unimaginative middle-class personality, content but vulnerable to upset when disturbed by unfavourable social or economic conditions. Already in 1847, Ludwig Pfau composed a poem with the title „Herr Biedermeier“, and it begins like this:

Schau, dort spaziert Herr Biedermeier

und seine Frau, den Sohn am Arm;

sein Tritt ist sachte wie auf Eier,

sein Wahlspruch: Weder kalt noch warm.Ludwig Pau, 1847

(Look, there strolls Herr Biedermeier / with his wife, who holds their son; / his step as soft as if he’s walking on eggs, / his motto: neither cold nor warm.)

Narrow-mindedness and double standards. Kleinbürgertum, petty bourgeoisie, piccola borghesia — Spießbürger, benpensante, Babbitt, Biedermann, bobo. The upwardly mobile — the upstarts, the parvenues, the social climbers, the nouveaux riches, the arrivistes and the arrivés alike — they were all characterised by conventional practicality and a lack of imagination, by mesquinerie, philistinery and bigotry. The p’tit-boo was petty, mean-spirited, rigid, prejudiced, parochial and provincial and suburban and insular, straight-laced, stuffy and stupid. Shrewd, possibly, but all the same: dumb.

This had all been reasonably friendly. Then came Karl Marx and gave the petite bourgeoisie the final whack, finishing the p‘tit-boos off, completely and scientifically. Marx used the term to identify the lowest socio-economic stratum of the bourgeoisie, which comprised small-scale capitalists, such as the traditional small shop-keepers, but also the foremen: former proletarians who now managed, in this brave new industrialised era, the workers as well as the production means owned by their haut-bourgeois employers. The contempt of the (socialist) working classes towards these people wasn’t so much connected with their social or their economic position, but was directed against the ambiguity of their political position. The term had acquired a political dimension. The p’tit-boo had become the enemy.

Now the petits bourgeois were not only derided by the rich, they were zealously fustigated by the proletariat, too.

According to Marx, the petite bourgeoisie was a floating class that would disappear with the advancement of insight and revolution: the ambiguity of their political and the precariousness of their economic situation, combined with the fluidity of their social position made them extremely vulnerable — for the p’tit-boo, it can go up and it can go down, quickly and unexpectedly. Marx admits that some members of “petit bourgeois Socialism” had dissected with great acuteness the existential conditions of the Industrialist era. Their solutions, however, were either utopian or reactionary; ultimately, the petite bourgeoisie would either sink into the proletariat, or disappear in the torrents of history with the rest of the bourgeoisie.

Ultimately, when stubborn historical facts had dispersed all intoxicating effects of self-deception, this form of Socialism ended in a miserable fit of the blues.Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto, 1848

This spectre is still haunting the petite bourgeoisie of yesterday, and its grandchildren of the twenty-first century, the bobos. It must be said, though, that Marx — however brilliant otherwise in his analysis — swept too many of the “petty bourgeois socialists” under the utopian-reactionary carpet. With hindsight we may say that any solution that is less bloodthirsty than a revolution would be preferable — provided that it is a solution, and here again Marx was unsurpassed in his predictions of the cunning of capitalism…

But I’m digressing.

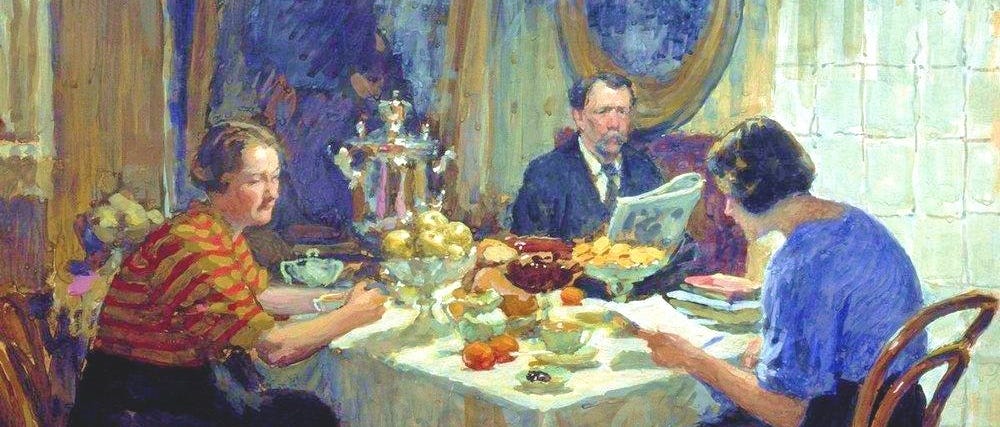

In fact, though there have been many depictions of the petite bourgeoisie in literature as well as in other forms of art, based on this image of petty stuffiness and narrow-mindedness, the realities of the petite bourgeoisie throughout the 19th and 20th centuries were far more complex. Most of all, and this is something that Marx in his sweeping condemnation of his bosom-enemies (i.e., all other socialists) was happy to not elaborate on: the petite bourgeoisie was not en bloc sold to self-interest and exploitation of the working class — and besides, even proletarian is as proletarian does.

According to this article some 29% of people living in the proud Karl-Marx-Hof and other municipal housing blocks in Vienna vote for the FPÖ, Austria’s extreme-right populists; the socialist party is losing its absolute majority even here, in those former bastions of the social democracy, where up to 71% used to vote Red. What remains of the working classes in the twenty-first century displays some of the most vile and repulsive racism, bigotry and Islamophobia of the country. The book of Didier Eribon, Retour à Reims (2009), describes the same evolution in the former communist working-class neighbourhoods in his hometown, Reims.

I rather agree with Aristoteles that a virtuous person will do virtuous things, no matter what social class she belongs to. Novelists certainly, bless their little hearts, always had an eye for the importance of someone’s moral stance and ethical choices and behaviours.

Back in the nineteenth century, Charles Dickens, in Our Mutual Friend (1865), set out the lines very neatly with three of his most memorable characters: the near-proletarian but high-aspiring Bella Wilfer and the faux-bourgeois Lammles. As has been remarked before, it can certainly go either way with the petite bourgeoisie.

The adorable Bella — a “mercenary young woman” with ”no more character than a canary bird” — sets out to get rich, as she explains to her indulgent father:

’That’s it, Pa. That’s the terrible part of it. When I was at home, and only knew what it was to be poor, I grumbled but didn’t so much mind. When I was at home expecting to be rich, I thought vaguely of all the great things I would do. But when I had been disappointed of my splendid fortune, and came to see it from day to day in other hands, and to have before my eyes what it could really do, then I became the mercenary little wretch I am.’

‘It’s your fancy, my dear.’

‘I can assure you it’s nothing of the sort, Pa!’ said Bella, nodding at him, with her very pretty eyebrows raised as high as they would go, and looking comically frightened. ‘It’s a fact. I am always avariciously scheming.’Charles Dickens, Our Mutual Friend: Chapter 8

Bella will come to understand the relative value of money, find true love and Eudaimonia. The hilariously loathsome Mr Alfred Lammle and Mrs Sophronia Lammle, on the contrary, who married each for the other’s non-existing wealth, are riding for a fall. Scheming and swindling, cold and greedy and manipulative and thoroughly deserving of one another, their downfall is inscribed in the unholy pact they make when they discover the truth:

’Possible! We have pretended well enough to one another. Can’t we, united, pretend to the world? Agreed. Secondly, we owe the Veneerings a grudge, and we owe all other people the grudge of wishing them to be taken in, as we ourselves have been taken in. Agreed?’

‘Yes. Agreed.’

‘We come smoothly to thirdly. You have called me an adventurer, Sophronia. So I am. In plain uncomplimentary English, so I am. So are you, my dear. So are many people. We agree to keep our own secret, and to work together in furtherance of our own schemes.’

‘What schemes?’

‘Any scheme that will bring us money. By our own schemes, I mean our joint interest. Agreed?’

She answers, after a little hesitation, ‘I suppose so. Agreed.’ (…)

So, the happy pair, with this hopeful marriage contract thus signed, sealed, and delivered, repair homeward.Our Mutual Friend, Chapter 10

Literature, as always, is better adapted and more powerful at showing complexity, ambiguity and dilemma — is more subtle, precise, and more penetrating in its analysis than Theory. There is no place in the revolution for p’tit-boos in traditional Marxist theory. A capitalist is someone who controls the means of productions and makes a profit exploiting the wage labour and of others. So far so good. You run a little café, you employ a waiter or two — you extract a surplus value from their labour, you are a contra-revolutionary. The role of pro-revolutionary individuals from non-revolutionary classes seems to be inexistent.

But let’s not, ever, forget that it was the combative members of the bourgeoisie — including the petty bourgeoisie and the impoverished bourgeoisie — who were some of the great driving forces behind the movements of the nineteenth and twentieth century.

They were reformers, socialists, novelists, anarchists, feminists, political writers, suffragettes, abolitionists, novelists, philanthropists. They took part in social and political battles, they supported the workers, the women, the minorities, the poor and the needy, and they helped to create political awareness and class consciousness by educating, funding, marching, writing, propagating and singing. They were Gutmenschen and idealists, and they were larger than life, some of them. Mary Wollstonecraft, for example, writer and feminist, belonged to the (impoverished) lower middle-class. Amos Bronson Alcott and Amy May Alcott, a couple with immense dreams of a better world, and incidentally the parents of Louisa May Alcott, were high middle class to start with (it didn’t last). The two most important revolutionary communists of the nineteenth century themselves, flamboyant Karl Marx, who was born in Trier to a middle-class family, and Jenny Marx, who belonged to the Prussian aristocracy (it didn’t last). Charles Dickens, writer and campaigner, fierce critic of the injustices of Victorian society, belonged to the impoverished middle class. Emmeline Pankhurst was a militant suffragette and a small business owner. Simone de Beauvoir, existentialist and fellow traveller, came from the impoverished middle class. Jacques Brel was a former boy scout from a prototypical bourgeois family who became a poet, singer and the scourge of the bourgeoisie.

Why, then, the hate and derision? It’s complicated. Some of the most inspired and influential critics seem to be protesting rather too much, too busily distancing themselves from their backgrounds. But the disdain from all sides is first and foremost due to the inherent ambiguity of this social class:

On the one hand, some of the p’tit-boos have too much money, or are too snobby, or truly believe that they are the betters of their employees, to be comfortable with the working classes — having become small-scale capitalists themselves, they now become interested in maintaining the status-quo. This kind of reactionary petite bourgeoise is the last girl on the planet to show solidarity with the working classes. She knows, or thinks she knows, what side her bread is buttered on.

On the other hand, consider the precariousness of the petit bourgeois, who is threatened and derided by the very system he is serving. The p’tit-boo who tries to imitate — within his limited means — the style and living standards of the grande bourgeoisie, is more often than not snubbed by his nose-pinching “betters”. Endeavouring to reflect the political-economic ideals of the wealthy elite, and having become the accomplice and minion of the bourgeois capitalist, the petit bourgeois quite often imbibes the morality (or, rather, lack thereof) of capitalism, and acquires the mean little soul, the corrupt morals, the bigotry and the philistinery and the petty-mindedness so often ascribed to him.

The rich and the poor, the Marxists, the artists and the intellectuals unite in their contempt. Climbing up or tottering down, the petite bourgeoise is doomed to disdain, scorn and mockery. If she shows that she has a soul, and ethical principles for which she is willing to sacrifice some of her comfort zone, the laughter becomes positively diabolical.

The Twentieth Century

The early twentieth century witnessed the petite bourgeoise in her suburban castle. Mrs Harrison, in Dorothy L. Sayers’ delightful epistolary crime novel, The Documents in the Case, is your perfect wannabe femme fatale of Suburbia. All the social markers (for Sayers was no mean snob herself) are pithily described by John Munting, the intellectual in the case:

“I didn’t think much of Mrs H. — she’s a sort of suburban vamp, an ex-typist or something, and entirely wrapped up, I should say, in her own attractions, but she’s evidently got her husband by the short hairs. Not good-looking, but full of S.A. and all that. He is a cut above her, I imagine, and at least twenty years older; small, thin, rather stooping, goatee beard, gold specs. and wears his forehead well over the top of his head. He has a decentish post of some kind with a firm of civil engineers. I gather she is his second wife, and that he has a son en premieres noces, also an engineer now building a bridge in Central Africa and doing rather well. The old boy is not a bad old bird, but an alarming bore on the subject of Art with a capital A. (…)Dorothy L. Sayers, The Documents in the Case (1930): Letter Nr. 5

Mrs H. is a nasty bit of goods, and an uncannily accurate prediction of the worst that was to come.

For there is an undeniable shady political side to the class of the petite bourgeoisie.

The always insecure p’tit-boos are in dire need of the status quo, of social stability and stable economic conditions — and never did this need become so obvious, or did the dapper little man turn so nasty, as in the first half of the twentieth century.

Fascism gave the disparaged and frightened mean little souls the means to kick back, and kick back with all the vileness of which human beings are capable. It was the ultimate collaboration of a politically reactionary brood with a system that was cut to their measure and appealed to all that was worse in them. Nobody, during the interbellum, had so much to lose as the petite bourgeoisie. Due to their existential insecurity, the instability and precariousness of their social and economic situation, many of them were apt to behave like cornered rats, and that’s exactly what many of them did — thus becoming the very backbone of fascism.

The “Red Years” in Italy, 1919–20, saw the p’tit-boos terrified by the Bolsheviks and the liberal-minded alike, resentful of the haute bourgeoisie and the intelligentsia in equal measures. This incarnation of the petite bourgeoisie believed in, and absolutely relied on, patriarchal family structures. Small businesses, according to Wilhelm Reich, are often self-exploiting enterprises of families headed by the father: their morality (and the underlying sexual repression) binds the family together in their precarious existence. Grasping at a promise of order and stability, these p’tit-boos tried to save their bacon by means of an unholy alliance with Mussolini and the Fascists.

Mussolini, in the name of preserving law and order, took advantage of the situation by allying with industrial businesses and attacking the workers and the peasants. A similar phenomenon could be witnessed in the Weimar Republic. Hitler, who learned a lot of his tricks from Mussolini, would eliminate “degenerates” and the political opposition by forcing them into slave labour, in collaboration with leading German corporations such as Thyssen, Volkswagen, IG Farben, Bosch, Philips, Siemens, and Volkswagen, to name but a few.

Already in the early thirties, Bertolt Brecht had started to explore the petit bourgeois mind. A Marxist himself, Brecht was extremely contemptuous of Nazism — as they were of him. Hitler’s brownshirts disrupted performances of Brecht’s plays, and accused him of “contaminating” the German stage with Jewish and black musical influences. Brecht repeatedly represented the petite bourgeoisie throughout his work, most famously in The Seven Deadly Sins of the Bourgeoisie. Anna and Anna, two sisters from Louisiana, set out to find their fortune in the big cities, so that their family will have enough money to build a little house on the banks of the Mississippi. In the last scene Anna, exhausted by sinning through the first six Deadly Sins, succumbs to the seventh, envy:

And the last big town we came to was San Francisco. Life there was fine, only Anna felt so tired and grew envious of others: of those who pass the time at their ease and in comfort; those too proud to be bought; of those whose wrath is kindled by injustice; those who act upon their impulses happily; lovers true to their loved ones; and those who take what they need without shame.

Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weil, The Seven Deadly Sins of the Petite Bourgeoisie

After the great purge of the war and the destruction of their short-lived, hysterical dreams of grandeur, the little shopkeepers and other p’tit-boos, collaborators and members of the resistance alike, piped down and attempted to smooth their ruffled feathers and reestablish themselves — and those born after the war washed their hands of the past and enjoyed the economic boom.

The petite bourgeoisie died out with the generation of my parents, honest hard-working members of the working class who had become petits bourgeois through no extraordinary efforts on their part — the fifties and sixties being what they were — and who were proud of their achievements. They retained the class consciousness of the proletariat, they knew the value of solidarity and voted for the social democrats, but they, too, had discovered what side their bread was buttered on.

This class slowly started to die out by the end of the Seventies, through lack of offspring. Marx had predicted that they would disappear through constant reinvention of the means of production. In fact, they were smothered by their modest luxury and the feeling that they had made it. Already in 1960, Max Horkheimer noted that the traditional social classes were crumbling, and that the workers in the industrialised countries had for the greater part become lousy, mean petits bourgeois (“miese Kleinbürger”), although he had to admit that the economic exploitation of the working classes had diminished, which I think goes the longest way to describe the decreased revolutionary mood of the traditional proletariat.

”Miese Kleinbürger” is a knee-jerk reaction, a lousy, mean little way to describe political opponents — if that is what they are. But why this propaganda? And why do we buy into this class-blaming? Why do we love to hate the p’tit-boo and her granddaughter, the bobo — who, like the generations before her, might have too much money for a good conscience, and possibly not enough spine to do some real good?

Because nobody wants to be a mean little capitalist (except Thatcher, bien entendu). Nobody wants to be no longer young, and having become bigoted, suburban and narrow-minded. Nobody likes to admit that the fire has died out and the mojo has gone, and that one has not become the intellectual or the artist of one’s dreams. Indolence and lethargy and complacency — but maybe sometimes some of that quietly desperate feeling creeps over you, in the knowledge that you have settled down comfortably, for the rest of your life.

Most of all, nobody wants to be suspected of having a weak spine, ethically. Nobody wants to be suspected of having not only a small car and a cramped little front yard, some wee little children and a nasty shrimp of a Pekinese, but also a mean little soul.

The following poetically vitriolic song by Jacques Brel (who certainly knew what he was talking about) from the sixties — when the petite bourgeoisie was still in full vigour — describes in all grotty details the viciousness of the petite bourgeoisie family of his beloved Frida, the petite bourgeoise who will never leave those people. Watch Brel’s splendidly cruel performance, with English subtitles:

Qui fait ses petites affaires

Avec son petit chapeau

Avec son petit manteau

Avec sa petite auto

Qu’aimerait bien avoir l’air

Mais qui n’a pas l’air du tout

Faut pas jouer les riches

Quand on n’a pas le souCes gens-là, 1966

But they weren’t all mies, or méchant, mean and greedy and grasping, as Horkheimer and Brel would have it. They, or their parents, had lived through and survived the second world war, and they now lived the good life in a miniature kind of way. And they sent their children to University, in the hope of an even better life.

And here we are, having had an education and acquired ideas above our status.

“La Libertà. Dunque, per me la Libertà è fare quello che mi pare. . . È essere libero. È. . . È. . . È la libertà di stampa e di pensiero. . . È. . . come posso dire?!. . . È una bella cosa. . . peccato che ce ne sia troppa!”.

Vincenzo Cerami. Un borghese piccolo piccolo. 1976

(”Liberty. Well, liberty is doing as I please. . . It means being free. It’s. . . It’s. . . It’s freedom of press and freedom of speech. . . It’s. . . Hoe can I say this?!. . . It’s something beautiful. . . Just a shame that there is too much of it!”)

Sothere we are, you see. According to the Great British Class Survey (2013) and the economist Guy Standing (The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class, read here or watch his lecture here), there exist now seven social classes (in Great Britain, but the analysis is valid for the rest of Europe). Newly emerging is the poorest social class, the Precariat, which constitutes roughly 15% of the population. They earn around or under what is considered a minimum standard of living, they have negligible saving and they usually rent. They live with a daily, continuous existential insecurity: one false move, one piece of bad luck, and they could be out on the streets. This is also the first class in history who is too well educated for the jobs they are forced to do. The precarious are systematically losing their rights: their civil rights, cultural rights, social rights, political rights.

Under the Precariat is a Lumpenproletariat of people dying in the streets of misery and hunger. They used to be out of sight, tucked away in their so-called Third World, but not any longer. The flotsam and jetsam of worldwide neoliberal capitalism are drifting on our seas and washing up in our streets — the lagan covering the beds of the seas.

There is no more petty bourgeoisie in this new scheme of things. So where have they gone to?

In the early eighties we saw the rise of the yuppie — a really unambiguously nasty beast. The yuppie was a Thatcher-created, predatory monster that rode the Big Bang waves and rose on the economic bubbles of speculation made possible by Thatcherite deregulation and liberalisation. It was a creature wholly consisting of greed, lust, pride and gluttony. The yuppies had none of the respectability that was, for good or for worse, a trademark of the petit bourgeoisie.

Their children and grandchildren, in a kind of mild opposition, became the bobos of today.

The last and positively brilliant upsurge of cultural petite bourgeoisie mockery erupted on British TV in the nineties: Keeping Up Appearances starring Hyacinth Bucket, the ”lady of the house speaking”. Note that the viciousness, the visceral hate, has disappeared — for in reality Hyacinth Boucqet, at this point, already belonged to an earlier epoch.

“It’s my sister Violet — the one with a Mercedes, swimming pool and room for a pony.”Keeping Up Appearances, Hyacinth Bucket, pronounced Bouquet

Oh yes, most certainly the terrifying Mrs Elton, with the sister at Maple Grove and the barouche-landau, and Hyacinth Bucket are sisters under the skin.

The new petite bourgeoise lives in Boboville and is likely to be a Gutmensch. Her parents, possibly proletarians, sent her to University, and she became working class with an attitude, petite bourgeoise without the money but with the humanities degree. She used to be rather bohemian but it’s wearing thin. The new intellectual petit bourgeois thinks that there is nothing wrong, maybe, with a little bit of capitalism, if you do it, you know, the right way. He discovered that working conditions have become lousy and precarious — there is no place for solidarity, because everybody else has become the competition. These bobos are growing noiselessly desperate, living a quiet, lonely precariousness. It’s difficult to be open-minded and liberal when your existential securities are continuously under threat.

Of course, compared to he people who are sold on slavery markets in Libya or drown in the Mediterranean, compared to the people and children in Bangladesh who are working under the worst of conditions to produce the clothes in my wardrobe, compared to the people who slave away in China for the Mac I’m typing on, or the people and, again, children who are working under slavery conditions in the Congolese mines for the cobalt in all my electronic devices, we all belong to the capitalist, reactionary haute bourgeoisie.

And the small shopkeeper, she hardly exists anymore. There is no bakery around here in my neighbourhood that doesn’t belong to a chain. The classic petit bourgeoisie, the owners of small bookshops and flower-shops and the little restaurants, the baker, the tailor and the shoemaker are being gorged up, eaten alive, driven out by Amazon Electronics, Amazon Baby Stuff, Amazon Pantry (“Save gas, save money, save time”, the infernal cheek), Amazon Books and Amazon Everything Else. (Amazon is number 6 in the WEF biggest world corporate giants, the 1% that dominates the world).

A smoked salmon socialist, a gauchiste caviar, and a bourgeois bohémien enter a champagne bar.

… The mind boggles.

Are these new petits bourgeois still the enemy?

Well, the enemy of whom? The working class? What was once the working class has become, for one part, the petite bourgeoisie of yesterday and bobohood of today: small house, freight bicycle, one wee child and a small holiday once a year. Scratching and biting, some of them, same as they ever were, only living even more precariously than before. But where is the rest of the proletariat nowadays? Where is the confident working class, the politically educated miners, steelers, car factory workers? Who are the people who sell their labour, own no means of production, have no capital but have saved a lifetime to buy their own house and send their children off to a good start in life? Do they now own too much to be part of the revolutionary elites? It seems that the other part of the once proud working classes has become “historical”.

The Precariat has taken their place, and the Precariat, as yet, has no class consciousness or concept of class solidarity — they are just slowly becoming aware that they belong to a class. And while the political left is stuck in a rut of leftishy discourse that has no connection whatsoever with the realities of the twenty-first century, the political right takes this new Precariat by storm.

Throughout this short history of the petite bourgeoisie, one thing has become exceedingly clear: Like Bella Wilfer, who thought that she could buy her Eudaemonia with money, we need to understand that everything depends on our moral stance — as it always has.

We — the precarians, the bobos, the Gutmenschen, the baby boomers and Generation X and the millennials and of course the teens of today — we cannot be complacent. There is no more time left to sit quietly around and be desperate. We are all far better educated than ever before in history. Those of us who have had the good luck of receiving an excellent education — and, yes, that degree in humanities is the most precious gift imaginable — let’s make use of it.

“Creating a good society is what all of us should do, however tiny our contribution might be.”

Guy Standing

Over the last thirty years, neoliberalism has constructed a global market economy where the 1% lords it over the rest of us. World’s labour supply has quadrupled, and this is not an accident — Marx’ “reserve army of cheap labour”, this underclass of Lumpenproletariat and desperadoes, is desired by global capitalism.

“Modern Industry has converted the little workshop of the patriarchal master into the great factory of the industrial capitalist. Masses of labourers, crowded into the factory, are organised like soldiers. As privates of the industrial army they are placed under the command of a perfect hierarchy of officers and sergeants. Not only are they slaves of the bourgeois class, and of the bourgeois State; they are daily and hourly enslaved by the machine, by the overlooker, and, above all, by the individual bourgeois manufacturer himself. The more openly this despotism proclaims gain to be its end and aim, the more petty, the more hateful and the more embittering it is.”The Communist Manifesto, 1848

Divide and Conquer. The neoliberal leaders of our Technological Revolution, in cohorts with the right-wing populists and extremists, feed upon the alienation and the anxiety and the — let’s not forget! — justified anger of all who live in precarious circumstances, and fuel hate, egoism, greed, xenophobia, asocial behaviour — playing, in fact, on the worst of irrational and asocial tendencies in human beings. And, predictably but not less dangerously, the hates and fears of the Precariat are directed against the new and desperate Lumpenproletariat, hitherto so well hidden in the so-called Third World, but now washing up on our shores — this flotsam and jetsam of neoliberal capitalism, a hotbed of fear and anger in and of itself, and at the same time a haunting spectre and an imminent threat to those who are already leading a precarious existence.

But all our jobs are in danger.

There is not a European, and an American, and an Asian, and an African Precariat — there is a global Precariat. The precariousness of the traditional petite-boos, the vulnerability of bobohood, and the desperation of the Lumpenproletariat are all part of one, globalised system. The loneliness of the freelancing web designer, the anxiety of the owner of the last grocery shop in the neighbourhood, the growing anger of the underpaid and overworked dishwasher, and the desperation of the sans-papiers immigrant are all the result of a worldwide neoliberal capitalist system that causes existential precariousness for most of the people — we, the 99,9%.

So what we need is, to put is extremely briefly, good old solidarity. Intergenerational, intergender, interclass, intercontinental, international solidarity. Let us not make the mistakes of those cornered rats, our fascist great-grandparents. Or of our charming and self-indulgent grandparents and parents. Or, god forbid, of our yuppie cousins.

We live in a globalised world: what we need is collaboration, not competition. We need to let that empathy blossom. We need to be proud of our bobo bleeding hearts. We need to learn, for the sake of goodness, how to be a mensch — a staunch and combative mensch.

“Creating a good society is what all of us should do.” Repeat: “Creating a good society is what all of us should do, however tiny our contribution might be.”

The Schlechtmensch is afraid of good intentions. She should be.

Bobos of the world, Unite!

—

Further Reading

Brecht, B., & Weil, K. (1933). Die sieben Todsünden der Kleinbürger. Ballet chanté (The Seven Deadly Sins of the Petty Bourgeoisie). Premiere 7 June 1933, Théatre des Champs-Elysées, Paris. A download of the text in German and English is available here, and you can watch a performance by Ute Lemper here.

- Brel, J. (1966). Ces gens-là. Watch Brel’s splendid performance, with English subtitles, here.

- Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1848). Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (Manifesto of the Communist Party). London: Communistischer Arbeiterbildungsverein. English text downloadable here.

- Krugman, Paul (November 24, 2011). “We Are the 99.9%”. The New York Times.

- Leygerman, D. (2018). “The Teens Will Save Us”. Dina Leygerman on Medium

- Sayers, D. L., & Eustace, R. (1930). The Documents in the Case. London: Victor Gollancz.

- Standing, G. (2011). The Precariat: The Dangerous New Class. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic. Read here or watch his lecture here.

WRITTEN BY