by NASA

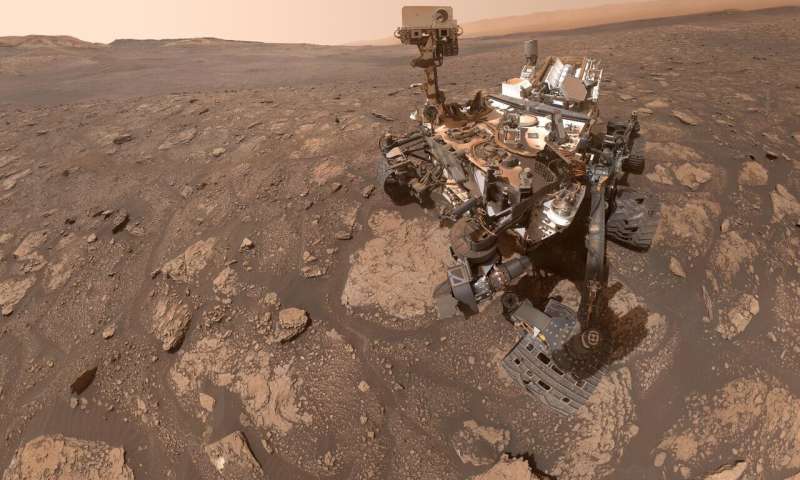

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover took this selfie at a location nicknamed "Mary Anning" after a 19th century English paleontologist. Curiosity snagged three samples of drilled rock at this site on its way out of the Glen Torridon region, which scientists believe preserves an ancient habitable environment. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover has a new selfie. This latest is from a location named "Mary Anning," after a 19th-century English paleontologist whose discovery of marine-reptile fossils were ignored for generations because of her gender and class. The rover has been at the site since this past July, taking and analyzing drill samples.

Made up of 59 pictures stitched together by imaging specialists, the selfie was taken on Oct. 25, 2020—the 2,922nd Martian day, or sol, of Curiosity's mission.

Scientists on the Curiosity team thought it fitting to name the sampling site after Anning because of the area's potential to reveal details about the ancient environment. Curiosity used the rock drill on the end of its robotic arm to take samples from three drill holes called "Mary Anning," "Mary Anning 3," and "Groken," this last one named after cliffs in Scotland's Shetland Islands. The robotic scientist has conducted a set of advanced experiments with those samples to extend the search for organic (or carbon-based) molecules in the ancient rocks.

Since touching down in Gale Crater in 2012, Curiosity has been ascending Mount Sharp to search for conditions that might once have supported life. This past year, the rover has explored a region of Mount Sharp called Glen Torridon, which likely held lakes and streams billions of years ago. Scientists suspect this is why a high concentration of clay minerals and organic molecules was discovered there.

It will take months for the team to interpret the chemistry and minerals in the samples from the Mary Anning site. In the meantime, the scientists and engineers who have been commanding the rover from their homes as a safety precaution during the coronavirus pandemic have directed Curiosity to continue its climb of Mount Sharp. The rover's next target of exploration is a layer of sulfate-laden rock that lies higher up the mountain. The team hopes to reach it in early 2021.

Explore further Curiosity says farewell to Mars' Vera Rubin Ridge

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover has a new selfie. This latest is from a location named "Mary Anning," after a 19th-century English paleontologist whose discovery of marine-reptile fossils were ignored for generations because of her gender and class. The rover has been at the site since this past July, taking and analyzing drill samples.

Made up of 59 pictures stitched together by imaging specialists, the selfie was taken on Oct. 25, 2020—the 2,922nd Martian day, or sol, of Curiosity's mission.

Scientists on the Curiosity team thought it fitting to name the sampling site after Anning because of the area's potential to reveal details about the ancient environment. Curiosity used the rock drill on the end of its robotic arm to take samples from three drill holes called "Mary Anning," "Mary Anning 3," and "Groken," this last one named after cliffs in Scotland's Shetland Islands. The robotic scientist has conducted a set of advanced experiments with those samples to extend the search for organic (or carbon-based) molecules in the ancient rocks.

Since touching down in Gale Crater in 2012, Curiosity has been ascending Mount Sharp to search for conditions that might once have supported life. This past year, the rover has explored a region of Mount Sharp called Glen Torridon, which likely held lakes and streams billions of years ago. Scientists suspect this is why a high concentration of clay minerals and organic molecules was discovered there.

It will take months for the team to interpret the chemistry and minerals in the samples from the Mary Anning site. In the meantime, the scientists and engineers who have been commanding the rover from their homes as a safety precaution during the coronavirus pandemic have directed Curiosity to continue its climb of Mount Sharp. The rover's next target of exploration is a layer of sulfate-laden rock that lies higher up the mountain. The team hopes to reach it in early 2021.

Explore further Curiosity says farewell to Mars' Vera Rubin Ridge

Provided by NASA