DUTERTE MURDER INC.

Filipino mother and son shot dead by policeman lad to rest

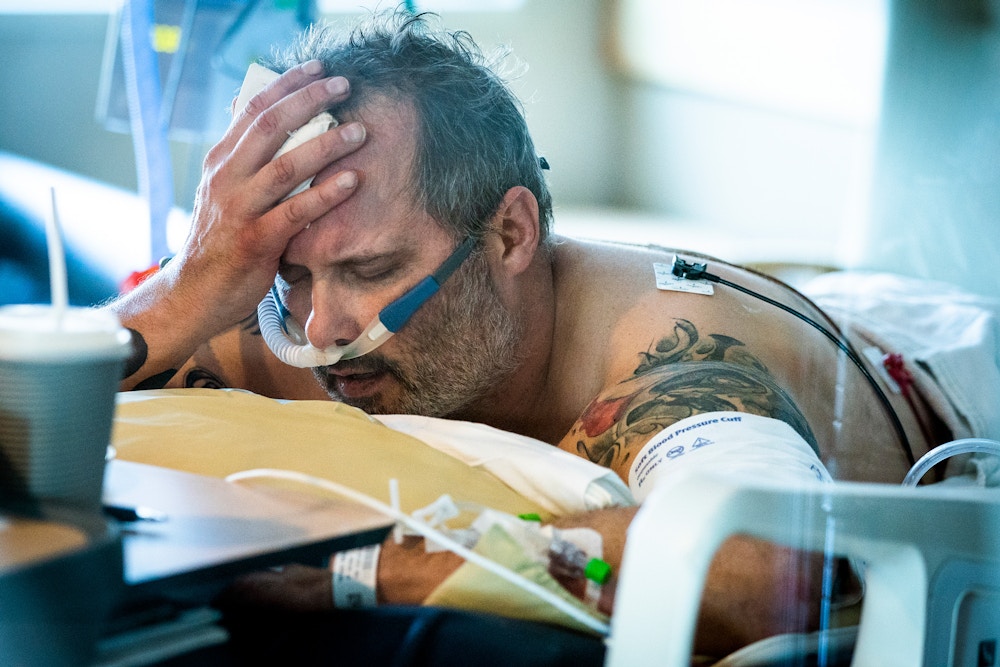

PANIQUI, Philippines: Hundreds attended the funeral on Sunday (Dec 27) of a woman and her son shot dead by an off-duty policeman in the Philippines, a week after a video of the incident went viral on social media, sparking public outrage over police brutality.

Members of the public joined as relatives and friends in Tarlac province, north of Manila, paid their final respects to Sonya Gregorio, 52, and her 25-year old son Frank Gregorio, who were shot in the head after a row over noise.

The shooting, which was recorded on a mobile phone by a member of the Gregorio family, triggered accusations from critics and human rights activists that President Rodrigo Duterte's war on drugs had created a culture of police impunity.

READ: Family mourns Filipino mother and son shot by police over noise

Policeman Jonel Nuezca was seen in the video engaged in a heated argument with the Gregorios over the use of a homemade noise-making device typically used to celebrate the New Year, before he shot the mother and her son

Nuezca surrendered to police on the night of the incident and faces two counts of murder. The government has promised a thorough investigation.

The victims' family has forgiven Nuezca but is still demanding justice, said Avelina San Jose, a relative of the Gregorios. "He should face the consequences of the law", she said.

READ: Duterte's pick for top cop causes stir over drug war deaths, lockdown party

Duterte, who has talked of killing criminals and issued promises to protect law enforcement while waging a war on drugs and crime, has condemned the shooting and warned "there will be hell to pay" for rogue officers.

Source: Reuters/dv