Discovered in the deep: Scientists exploring the uncharted waters of the Indian Ocean uncover a multitude of dazzling sea creatures around a remote Australian island group

A ferocious looking conger eel with large fang-like teeth was collected from a depth of 1,000 metres. Photograph: Benjamin Healley/Museums Victoria

by Helen Scales

Seascape: the state of our oceans

About this content

Mon 14 Nov 2022

A shipload of scientists has just returned from exploring the uncharted waters of the Indian Ocean, where they mapped giant underwater mountains and encountered a multitude of deep-sea animals decked out in twinkling lights, with velvety black skin and mouths full of needle-sharp, glassy fangs.

The team of biologists was the first to study the waters around the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, an Australian territory more than 600 miles off the coast of Sumatra. “It’s just a complete blank slate,” says the expedition’s chief scientist, Dr Tim O’Hara, from Museum Victoria Research Institute.

“That area of the world is so rarely studied,” says Dr Michelle Taylor from the University of Essex and president of the Deep-Sea Biology Society, who wasn’t involved in the expedition.

Few research expeditions make it to the Indian Ocean, chiefly because it’s so remote. It took the team six days to get to Cocos (Keeling) Islands from Darwin, in Australia’s Northern Territory, on the research vessel Investigator, operated by Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO.

The Sloane’s viperfish has huge fang-like teeth, visible even when the mouth is closed. It has light-producing organs on its belly and upper fin, which help disguise it from predators and lure prey. Photograph: Benjamin Healley

“The real stars of the show are the fish,” says O’Hara, who specialises in invertebrates. “There are blind eels and tripod fish, hatchetfish and dragonfish, with all of these bioluminescent organs on them and lures coming out of their heads. They’re just extraordinary.”

Among the huge variety of life they found, the deep-sea batfish was a highlight. It sits on the seabed like an ornate pancake and struts about on two stubby fins that act as legs. It wiggles a tiny lure tucked into a hollow on its snout, presumably hoping to trick prey into thinking it is a tasty worm.

Clockwise from top left: a deep-sea batfish; a voracious highfin lizard fish; tribute spiderfish on its ‘stilts’; a previously unknown blind eel. Photographs: Benjamin Healley

Advertisement

They spotted the tribute spiderfish, which has long lower fins it uses as stilts to perch above the seabed, catching passing morsels of food. They found a previously unknown blind eel, collected from 5,000m down, covered in jelly-like, transparent skin. And they saw stoplight loose jaws, a type of dragonfish, which have huge unfolding jaws with double hinges and the unusual habit of spying on other animals with red bioluminescent light, a colour which most deep-sea animals can’t see.

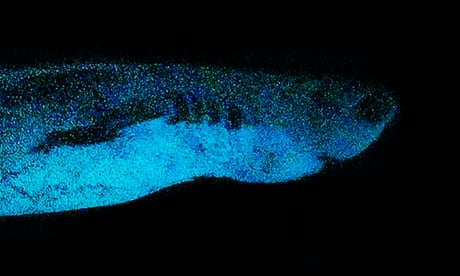

Discovered in the deep: the sharks that glow in the dark

Read more

A sampling net dragged across the abyssal plain came up full of ancient shark teeth. “They were gigantic sharks that lived millions of years ago,” says O’Hara. Based on photographs, fossil experts think these came from “megalodon-like animals”. They’ll know more once they get their hands on the teeth, which are now being sent to museums along with all the rest of the collections.

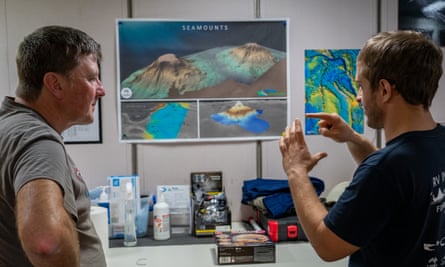

Scientists Nelson Kuna from CSIRO, left, and Tim O’Hara from Museums Victoria. Right, the RV Investigator. Photographs: Robert French and Mike Kuhn

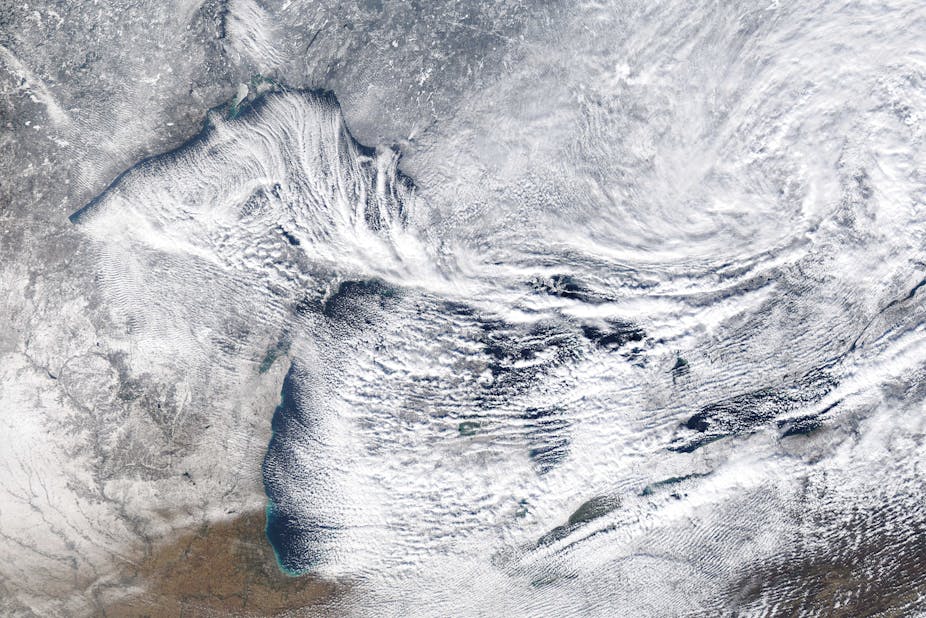

As well as shining a light on the deep-sea life of this unstudied region, the team also uncovered a dramatic seascape, including huge submerged volcanoes, or seamounts, which at 5,000 metres high are more than twice as tall as Australia’s highest land mountain. “From the surface you wouldn’t know,” says O’Hara.

The slender snipe eel, found at depths of up to 4,000m. With its long tail, it can reach a metre in length. Curved jaws, permanently open, are covered in tiny hooked teeth that snag their prey. Photograph: Yi-Kai Tea

Advertisement

Using high-resolution sonar, the team created detailed 3D maps of the deep seafloor, and discovered several smaller seamounts that were previously unknown.

Not only are many deep seamounts covered in rich habitats of corals, sponges and other wildlife, they play a crucial role in mixing the ocean. Deep currents sweep up the flanks of seamounts, bringing vital nutrients to the surface. “Some people call them the stirring rods of the oceans because they actually mix water at different levels,” says O’Hara.

One reason for going to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands was to provide baseline information to help manage and protect the newly established marine park there, set up in March 2022 with the nearby Christmas Island marine park, which the team visited last year.

A flatfish from the order Pleuronectiformes, left. Researchers also found ancient rocks and fossils, such as a tooth from a white shark, right. Photographs: Benjamin Healley

The area isn’t threatened by deep-sea mining because, as O’Hara says, geologists prospected for seafloor minerals and decided they weren’t worth exploiting. The main threat, according the team, was plastic pollution. “Even when you’re that far off the continent, at four kilometres deep, you’ll dredge up plastics,” he says. “You see it in the water, you see it on top of the water, and we saw it in our collections.”

It will take years for experts to work their way through all the specimens the expedition collected, but O’Hara estimates that between 10% and 30% will be species new to science. “I’m really excited about what new future science discoveries come out from this in the years to come,” says Taylor.

One thing the team already has planned is to match up DNA from the specimens with DNA snippets sifted from seawater, known as environmental or eDNA, which is shed by organisms in slime and skin cells. The idea is that in the future, scientists will be able to identify which species are present in the deep sea just from the genetic calling cards left behind in the seawater.

Deep-sea batfish move over the seafloor on their armlike fins. They have a tiny “fishing lure” in their snout which they wiggle about to help them attract prey. Photograph: Benjamin Healley

“Who knows what’s going to happen with those specimens in museums in 100 years’ time,” says Taylor. “Trying to maximise the science possible from each one of the specimens is so important, because it’s such a rare privilege to be able to visit these deep-sea areas.”

\

\