FLORIDA

Climate change heats devil fish that possess St. Johns River

I HAD TALIPIA FOR DINNER LAST NIGHT

2022/12/07

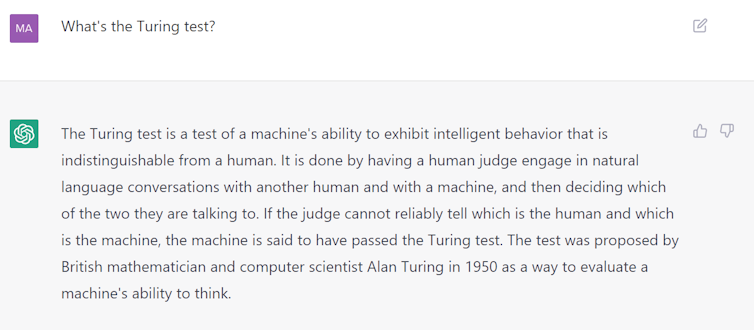

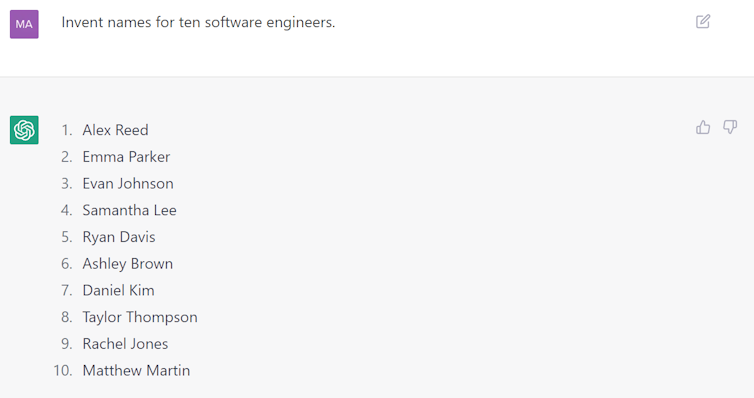

Radesh Arjoon fills a container with the day's catch of armored catfish at the boat ramp on Hwy. 50,

RAOUX/Orlando Sentinel/TNS

ORLANDO, Fla. — In another alarm of nature spiraling to hell in Florida, scientists suspect global warming has enabled devil fish to plague and ravage the St. Johns River.

This summer, a team of state water and wildlife experts with the help of a commercial fishing crew cast industrial nets in a Central Florida portion of the river several miles south of Cocoa called Lake Winder.

Of the estimated 40,000 pounds of many species hauled in for examination, only a small portion, less than 20 percent, was Floridian: bass, crappie, brim, catfish, bowfin and others.

The rest were exotics: a type from South America broadly known as armored catfish, some of which are known also as devil fish, and tilapia from Africa.

Since that exploratory outing, unanswered questions have loomed. Why are the invaders there, why do they vastly outnumber natives, are they mucking up water quality and are they mowing down essential aquatic plants in the river? Research plans are unfolding.

“We are in the early stages of investigating whether we can lay the blame on these exotic fish,” said Reid Hyle, a freshwater fisheries biological scientist with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute.

Those exotic invaders have been established in parts of Florida for decades but there hasn’t been much clarity on population numbers, Hyle said.

Also probing the disruption to fish populations is the St. Johns River Water Management District, a state agency responsible for the use and care of surface and under ground waters from Orlando to Jacksonville.

Scientists know that armored catfish tear up river bottoms for nesting and that tilapia consume aquatic plants – behaviors that may upset water quality and ecosystem balance.

“A bigger issue we suspect on why they are increasing over time is climate change,” said Erich Marzoff, the district’s director for water and land resources. “We just don’t have the frequency of hard freezes that we have had in past decades.”

The well documented rise in Florida temperatures has been particularly meaningful for the state’s warming winters, which has ushered a northern migration of aquatic plants, including mangroves, and fish, including snook, that aren’t particularly cold hardy.

Central Florida is a tipping point between freezes that rarely occur in South Florida and still occur somewhat often in North Florida.

Even in North Florida, however, tilapia and armor catfish have an increasing impact on the St. Johns River near Jacksonville.

Those exotic fish are “contributing to the decimation of eel grass that has been weakened by saltwater intrusion and more frequent hurricanes,” said Lisa Rinaman, leader of the environmental group St. Johns Riverkeeper.

To some extent, natives have learned to take advantage of or at least entertain themselves with the invaders, said Doug Sphar, a resident of Lake Poinsett, which is next to Lake Winder, and a longtime contributor to Florida’s environment.

“Tilapia are keeping the gators fat and happy,” Sphar said. “I often see and hear them taking on a big tilapia. They seem to play around with them like a dog with a new chew toy. I also see gators taking on armored catfish.”

Hyle said a major cold snap in 2010 massacred tilapia and armor catfish along the St. Johns River in Central Florida.

“The kill was extensive,” Hyle said. “It was amazing to go out on the St. Johns after that happened and go ‘wow, that’s how many of these things were out here.’”

For tilapia and armored catfish, lethal water temperatures start at the low 50s. They are more suited for tropical conditions of where they came from – waters of the Nile and Amazon river systems.

Fish are given a lot of different common names by nonscientists. The armored catfish netted in Lake Winder are called that because of their impressive scales. While cold wimps, they otherwise are tough as nails and can survive out of water for hours.

Two types of armor catfish were hauled in and they aren’t closely related.

One was the brown hoplo that can grow to about 10 inches in length. They nest by chewing vegetation into foamy spit balls that cradle eggs.

Largemouth bass and snook eat hoplos, which, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commissioner, also are “highly sought after as food by Floridians with cultural ties to Trinidad and parts of South America.”

Of the more than 1,000 pounds of brown hoplos netted by the researchers, they were quickly sold for $3.50 a pound.

The other armored catfish, a kind often seen in always-warm springs, such as Wekiwa and Blue in Central Florida, is sometimes referred to as a pleco, for plecostomus, a popular aquarium species.

They aren’t actually a pleco, a rather small fish, Hyer said. They are a vermiculated sailfin catfish, he said, which can grow to 20 inches and 3 pounds, which is why they have been dumped by aquarium hobbyists into lakes and rivers.

In Texas and Mexico, vermiculated sailfin catfish sometimes are called devil fish.

The research crew brought in 9,000 pounds of the fish. There is no market for them. Some were hauled to a landfill and others were released back to the river.

In public presentations on the Lake Winder findings, the water district has included the popularly known name of pleco and the attention-getting name of devil fish.

Also from the Lake Winder study, nearly 23,000 pounds of tilapia were sold for 58 a cent a pound.

Devil fish bore holes into river banks to nest. Tilapia dig potholes along river bottoms, leaving what looks like a moonscape of craters.

Both nesting behaviors are thought to stir up sediment and dislodge aquatic plants.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission on its website still describes devil fish, or vermiculated sailfin catfish as “occasionally found in Center Florida.”

“We really had no idea,” said Marzoff of the water district’s understanding of armor catfish populations in its flagship water body, the St. Johns River. “We suspected they were moving north and we had no good recent data.”

Along with pursuing research on the harm caused by the invading fish, the water district also is contemplating a remedy like one long implemented at Lake Apopka to get rid of a trash fish called gizzard shad that has a role in exacerbating water pollution.

The water district invites commercial crews to net as many Apopka shad as they can, which are sold typically as crab bait to offset the cost of removing the fish.

A public-private partnership like that may work to get rid of tilapia and armored catfish in the St. Johns River, Marzoff said. “We may not have to pay a whole lot.”