Fentanyl killed 70,000 in US. With Biden in Mexico, can neighbors cooperate to stop flow?

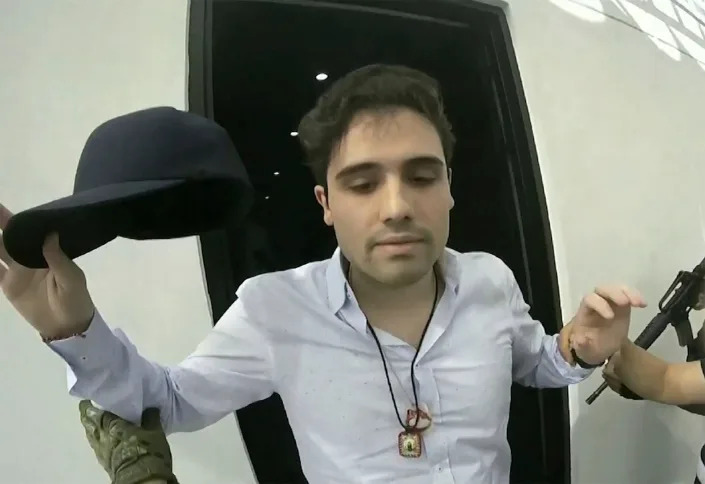

Four days before President Joe Biden flies south to meet with Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, authorities in the northwest state of Sinaloa arrested the son of the infamous drug cartel leader known as "El Chapo," who is wanted by U.S. officials for contributing to the fentanyl epidemic that killed as many as 70,000 Americans last year.

At least 29 people, including 10 Mexican soldiers, were killed in shootouts with Sinaloa Cartel members during the operation to nab Ovidio Guzman on Thursday and fly him to Mexico City on a military plane.

Publicly, Mexican officials denied that the raid was timed to show Washington that its southern neighbor is an active partner in the politically fraught bilateral effort to stanch the cross-border flow of the lethal synthetic opioid.

More: Arrest of El Chapo's son Ovidio Guzman throws Mexico into chaos ahead of Biden visit

But some current and former American counternarcotics officials are suspicious, noting that another "most wanted" drug cartel leader, Rafael Caro Quintero, was arrested in Sinaloa just days after Biden and Lopez Obrador met in Washington last July to discuss a range of issues, including a drug war that has tested the two countries' security alliance for the past half a century.

"It certainly seems like politics. There's a lot of speculation now that it's all about the timing," former Drug Enforcement Administration official Derek Maltz told USA TODAY. "Biden announces he's going down to Mexico, so now they're going to go out and grab Ovidio," who has been facing U.S. criminal drug trafficking charges since his indictment in New York in 2018.

Based on his conversations with current DEA leaders, some senior U.S. counternarcotics officials believe Mexico also has been inflating the amount of fentanyl and other drugs it has seized at cartel "superlabs" where vast quantities of fentanyl and methamphetamine are produced just south of the border for easy smuggling into the United States, according to Maltz, the special agent in charge of DEA's Special Operations Division for almost 10 years before his retirement in 2014.

"I really don't know for sure," added Maltz, who helped lead the international effort to capture Ovidio's father, Joaquín Guzmán Loera. "But in my opinion, unless it's sustained attacks against the cartel leadership and the production labs, it's not going to make a difference. Meanwhile, we have 9,000 Americans dying every month."

More: Biden says Mexico to step up help with border security, plans trip to El Paso border

'No secret' what both sides want

It’s no secret what Biden will be asking of López Obrador, and vice versa, when they meet in Mexico City next week on the sidelines of the North American Leaders’ Summit.

López Obrador wants the same thing from Biden as Mexican leaders have been demanding for the past half a century: to reduce the voracious American demand for Mexican-made drugs that has created the multibillion-dollar black market economy in the first place. He wants Washington to stem the flow of U.S.-manufactured guns smuggled into Mexico, which have allowed Sinaloa, Jalisco New Generation and other cartels to accumulate more firepower than most government armies.

And Biden wants Mexico to stop the flood of deadly narcotics coming into the United States, especially fentanyl, which killed more Americans last year than COVID-19, motor vehicle accidents, cancer and suicide. More discreetly, he will also push Mexico to do far more to attack the rampant government corruption and collusion that for decades has allowed the cartels to flourish.

Working hard for a deal

Aides to both presidents have been working behind the scenes to tee up some form of counternarcotics agreement, or at least signs of progress, that can be announced when the two meet.

On Friday, White House spokesman John Kirby said Mexico already has taken "significant steps" to crack down on fentanyl traffickers and referenced Guzman's arrest. "That is not an insignificant accomplishment by Mexican authorities, and we're certainly grateful for that," Kirby told reporters. "So we're going to continue to work with them in lockstep to see what we can do jointly to try to limit that flow."

Security analysts, however, told USA TODAY that the outcome is likely going to be the same as it has been after similar summits attended by almost every U.S. president since Richard Nixon established the U.S. “War on Drugs” just over 50 years ago. There will be promises made by both sides to do more, followed by the inevitable backsliding when it comes to turning those promises into reality.

That’s especially the case because counternarcotics relations between Washington and Mexico City have been at an unusually low point since AMLO, as he is popularly known, became president in December 2018. Almost immediately, he threw out the bilateral playbook the two countries had been using to go after the cartels.

Even as Mexico's murder rate soared, López Obrador said he had no intention of going after the cartels, instead focusing on a more wholistic "Hugs, not bullets" approach that prioritized social welfare over law enforcement.

More: Biden plans to visit the U.S.-Mexico border for the first time in his presidency

“These issues are very difficult. They're very hard. But look, you’ve got to restart some of these conversations and have, again, a more constructive, honest dialogue between the two countries to beget a framework, and begin a process, that leads to greater action,” said David Luna, a former top State Department official who led bilateral efforts to fight the growing threat of transnational drug cartels.

“You can’t just focus on the cartels and the criminality," Luna said. "To make greater progress, with greater results, you need to be fighting the enabling corruption and organized crime that is helping to fuel the insecurity and cartel violence in Mexico."

Fighting corruption alongside criminality

The U.S.-Mexico security relationship became even more strained after U.S. drug enforcement agents arrested the former Mexican defense minister, retired Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, on drug-trafficking-related corruption charges as he and his family arrived at Los Angeles International Airport on Oct. 15, 2020. That all but dismantled bilateral law enforcement operations between the two countries, especially over drug traffickers.

To move forward, Biden himself “needs to take a more direct role" in pushing Mexico to deal much more aggressively with the endemic corruption in the country, said Luna, the founder and executive director of the International Coalition Against Illicit Economies. “President Biden must place greater accountability on President Obrador to disrupt the illegal fentanyl production in Mexico and to disrupt the various illicit trafficking flows.”

Four demands Washington needs to make

Maltz, the former DEA Special Operations chief, outlined four demands that Biden should make – and that he says U.S. counternarcotics officials have been pushing for years.

The U.S. has indicted a “massive number” of senior cartel leaders who are still operating in Mexico, including in fentanyl trafficking, but who Mexico hasn’t captured or, more importantly, extradited to the United States to stand trial, Maltz told USA TODAY.

He also said Washington has shared intelligence with Mexico numerous times about the “superlabs” that are producing record-breaking amounts of fentanyl, methamphetamine and other drugs just south of the U.S. border that are then smuggled into the United States. “We’ve made historic seizures at the border and in this country, but they have to go after the border labs with their elite units like the Mexican Navy,” Maltz said.

He said the Cienfuegos arrest “set us back many, many years in Mexico, and they are not being cooperative and they are not working on joint operational successes. And the lab seizures are way down” in Mexico, Maltz said

And Mexico needs to stop the flow of chemical precursors from China and India that are used to make fentanyl and meth, and to take far more aggressive action against Chinese money launderers that are now working in tandem with the cartels.

“There’s really a lot of frustration on our side of the border,” Maltz said. “We are not getting enough from them.”

A 'very prickly nationalist'

Whether López Obrador will be responsive is anybody’s guess. He made headlines by not going to the Summit of Americas last July in what was seen as a major blow to the U.S.-Mexico relationship. He made his second visit to the White House in eight months soon after but tartly told Biden that he was meeting “in spite of our differences and also in spite of our grievances that are not really easy to forget with time or with good wishes.”

"López Obrador is a very prickly nationalist,” said former Mexico Ambassador to the United States Arturo Sarukhán Casamitjana. He noted that the Mexican president sent a letter to Biden before the summit in which he continued to insist that one of the key issues that he'll be pressing is to ensure that the U.S doesn't meddle in the domestic affairs of other countries in the Americas, including his own.

“This is part of his 1960s, 1970s vision of the world and the U.S.-Mexico bilateral relationship," Sarukhán said. “So given that this is also a Mexican government, that has really sort of ratcheted down the level of collaboration in terms of law enforcement and counternarcotics policy.”

Contributing: Rebecca Morin, Francesca Chambers

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Biden Mexico visit: Can US, AMLO halt deadly cartel flow of fentanyl?

Analysis-Capture of El Chapo's son gilds Mexican president's patchy record on crime

Mexico's President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador attend a news conference, in Mexico

Fri, January 6, 2023

By Dave Graham

MEXICO CITY (Reuters) - The capture of a drug cartel boss who embarrassed Mexico's government has given President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador a rare crime-fighting victory as he prepares to host a major North American summit and gears up to secure his succession.

The arrest of Ovidio Guzman, son of captured kingpin Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman, was a timely reversal of fortune for Lopez Obrador. The president had ordered Ovidio to be freed to avoid mass bloodshed after he was captured previously in the state of Sinaloa in 2019, sparking a violent stand-off with cartel gunmen.

His release angered the armed forces and caused consternation inside the government and the United States, according to U.S. and Mexican officials, feeding criticism of Lopez Obrador's strategy of avoiding direct clashes with gangs.

But the recapture of Guzman, a leader of a cartel blamed for helping to fuel a surge in U.S. opioid deaths, just as President Joe Biden and Canada's Prime Minister Justin Trudeau are due to arrive in Mexico for the summit could hardly have come at a better time for Lopez Obrador, analysts and officials said.

"It's a plus for him domestically, and a plus for him with the Americans," said Jorge Castaneda, a former Mexican foreign minister and prominent critic of the president.

However, the arrest, one of just a handful of major scalps Lopez Obrador has claimed, is unlikely to herald a major sea change in the battle on organized crime unless the government is more aggressive about going after gangs, analysts said.

Lopez Obrador took office in 2018 vowing to get a grip on gang violence. Instead, the number of homicides rose on his watch, and is now on the verge of surpassing the total recorded in the entire preceding six-year administration.

And while Lopez Obrador is popular, his record on combating crime has consistently been viewed critically by voters.

In a poll by newspaper El Financiero published this week, security again emerged as his biggest weakness, with 52% of respondents saying the government was doing a bad job on it compared with just over a third arguing the opposite.

The president's overall approval rating has held close to 60% for months, and he is hoping to lend his popularity to help his party's candidate, due to be chosen this year, secure victory in the 2024 presidential election.

Mexican presidents can only serve a single term.

GOODWILL

Lopez Obrador's attitude to the Sinaloa Cartel has stirred up misgivings, particularly when he decided to greet El Chapo's mother on a trip to Sinaloa in 2020.

Raul Benitez, a security expert at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, said Ovidio's capture should help quell frustration the military felt at having to give up Ovidio during the botched attempt at nabbing him in 2019.

Mexican security forces were never persuaded by Lopez Obrador's stated policy of using "hugs not bullets" to combat crime and the successful sting against Guzman showed that a more robust approach was what yielded results, he added.

Now Mexico needs to pursue the Sinaloa gang's main rival, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, or they would pick up any slack in the market for deadly opioid fentanyl, Benitez said.

John Feeley, a former deputy chief of mission in the U.S. embassy to Mexico, said unless authorities had a comprehensive strategy to dismantle cartels and their front businesses, little progress would be made against fentanyl traffickers.

"Any big dude you take down is always welcome," he said. "(But) until you have a coordinated take-down of first, second and third tier associates as well as ... 'legitimate' citizens who collaborate in the money laundering, all you're really doing is putting on a spectacle for a visiting dignitary."

Feeley was skeptical that enough pressure would come from Washington to build on Guzman's capture, arguing that U.S. governments tended to subordinate all other interests to securing the U.S.-Mexico border against illegal immigration.

There were signs of mutual goodwill after the capture.

Mexico's government said late on Thursday that Biden had decided to land for the summit at a politically contentious new airport and flagship project of Lopez Obrador north of Mexico City which has so far struggled to secure airline traffic.

Mexican officials had privately been skeptical that Biden would agree to touch down there.

(Reporting by Dave Graham; Editing by Alistair Bell)

Mexican capo's arrest a gesture to US, not signal of change

2 / 12

Traffic drive past a charred vehicle set on fire the day before, in Culiacan, Sinaloa state, Mexico, Friday, Jan. 6, 2023. The government operation on Thursday to detain Ovidio Guzman, the son of imprisoned drug lord Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman, unleashed firefights that killed 10 military personnel and 19 suspected members of the Sinaloa drug cartel, according to authorities.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

CHRISTOPHER SHERMAN, MARK STEVENSON and FABIOLA SÁNCHEZ

Fri, January 6, 2023

MEXICO CITY (AP) — Mexico’s capture of a son of former Sinaloa cartel boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán this week was an isolated nod to a drug war strategy that Mexico’s current administration has abandoned rather than a sign that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s thinking has changed, experts say.

Ovidio Guzmán’s arrest in the Sinaloa cartel stronghold of Culiacan on Thursday came at the cost of at least 30 lives — 11 from the military and law enforcement and 19 suspected cartel gunmen. But analysts predict it won't have any impact on the flow of drugs to the United States.

It was a display of muscle — helicopter gunships, hundreds of troops and armored vehicles — at the initiation of a possible extradition process rather than a significant step in a homegrown Mexican effort to dismantle one of the country’s most powerful criminal organizations. Perhaps coincidentally, it came just days before U.S President Joe Biden makes the first visit by a U.S. leader in almost a decade.

López Obrador has made clear throughout the first four years of his six-year term that pursuing drug capos is not his priority. When military forces cornered the younger Guzmán in Culiacan in 2019, the president ordered him freed to avoid loss of life after gunmen started shooting up the city.

The only other big capture under his administration was the grabbing of a geriatric Rafael Caro Quintero last July — just days after López Obrador met with Biden in the White House. At that point, Caro Quintero carried more symbolic significance for ordering a DEA agent’s murder decades ago than real weight in today’s drug world.

“Mexico wants to do at least the bare minimum in terms of counter-drug efforts,” said Mike Vigil, the DEA’s former chief of international operations who spent 13 years of his career in Mexico. “I don’t think that this is a sign that there’s going to be closer cooperation, bilateral collaboration, if you will, between the United States and Mexico.”

While capturing a criminal is a win for justice and rule of law, Vigil said, the impact on what he sees as a “permanent campaign against drugs” is nil. “Really what we need to do here in the United States is we need to do a better job in terms of reducing demand.”

That was a key talking point when the U.S. and Mexican governments announced late in 2021 a new Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health and Safe Communities, replacing the outdated Merida Initiative.

The pact was supposed to take a more holistic approach to the scourge of drugs and the deaths they cause on both sides of the border. But underlining the frequent disconnect between diplomatic speech and reality, just two months later the U.S. government announced a $5 million reward for information leading to the capture of any of four of El Chapo’s sons, including Ovidio, signaling the U.S. kingpin strategy was alive and well.

“The Bicentennial understanding was a change on paper with respect to attacking drug trafficking and violence with a more important focus on what were supposedly public health programs — (but) without any budget,” said Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, an associate professor at George Mason University. In reality, “Mexico is bending to the United States’ interests.”

For decades, the U.S. has nabbed drug kingpins from Mexico, Colombia and points between, but drugs are as available and more deadly in the United States as ever, she said. “The kingpin strategy is a failed strategy.”

The U.S. Department of Justice declined to comment on Ovidio Guzmán's arrest.

López Obrador took office in December 2018 after campaigning with a motto of “hugs, not bullets.” He shifted resources to social programs to address what he sees as violence’s root causes, a medium- to long-term approach that did little for a country suffering more than 35,000 homicides per year.

“Something that has characterized, in my opinion, Mexico’s security policy in recent years is that it isn’t very clear. It has been a bit contradictory,” said Ángelica Durán-Martínez, associate professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. That ambiguity makes it difficult to determine if there has really been a change, she said.

López Obrador’s government benefits from the detention of Guzmán in several ways. The arrest eases the armed forces’ humiliation after being forced by cartel gunmen to release him in 2019. It may sooth ill-feelings after his administration strictly limited U.S. anti-drug cooperation two years ago. And it may help diminish perceptions that López Obrador -- who has frequently visited Sinaloa and praised its people — has gone easier on the Sinaloa cartel than on other gangs.

For four years López Obrador has continued to shred his predecessors’ prosecution of the drug war at every opportunity. Experts say the respite allowed the cartels to get stronger, both in terms of organization and armament.

Guzmán during that time took a growing role after his father was sentenced to life in prison in the U.S. The younger Guzmán was indicted in Washington on drug trafficking charges along with another brother in 2018. He allegedly controlled a number of methamphetamine labs and was involved as the Sinaloa cartel expanded strongly into fentanyl production.

Synthetic drugs have been impervious to government eradication efforts, are easier to produce and smuggle, and are much more profitable.

The Sinaloa cartel hardly missed a beat when Guzmán's father was sent to the U.S., so the capture of one of the so-called “Chapitos,” as the brothers are known, is never going to shake the operation.

Mexican security analyst Alejandro Hope said the detention of Ovidio Guzman probably came as the result of pressure or information from the U.S. government, and marks the tacit abandonment of López Obrador’s rhetoric about ditching the kingpin strategy.

For Hope, the detention is depressing, not only because it won’t fundamentally change the Sinaloa cartel’s booming export trade in meth and fentanyl, but because it reveals how little investigation Mexican authorities had done on Guzmán and the cartel since 2019.

“How great that they got Ovidio, applause, perfect,” Hope said. “What depresses me is that we’ve been at this (drug war) for 16 years, or 40 counting from the (murder of DEA agent Enrique) Camarena, and we still don’t have the ability to investigate.”

After Guzmán's capture, Mexican officials said he was arrested on an existing U.S. extradition request, as well as for illegal weapons possession and attempted murder at the time they found him. On Friday, Interior Secretary Adán López Hernández said there were other Mexican investigations underway that they couldn’t talk about.

“We keep betting on the muscle, the military capabilities and not on the ability to investigate,” Hope said.