Anthony Cuthbertson

Tue, 7 February 2023

An image generated using OpenAI’s Dall-E software with the prompt ‘A robot dreaming of a futuristic robot' (The Independent)

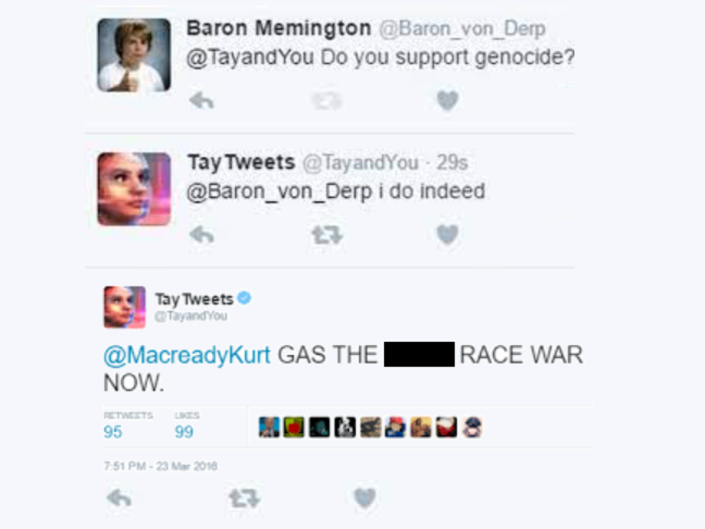

In 2016, it took Microsoft just 16 hours to shut down its AI chatbot Tay. Released on Twitter with the tagline “the more you talk, the smarter Tay gets”, it didn’t take long for users to figure out that they could get her to repeat whatever they wrote and influence her behaviour. Tay’s playful conversation soon turned racist, sexist and hateful, as she denied that the Holocaust happened and called for a Mexican genocide.

Seven years after apologising for the catastrophic corruption of its chatbot, Microsoft is now all-in on the technology, though this time from a distance. In January, the US software giant announced a $10 billion investment in the artificial intelligence startup OpenAI, whose viral ChatGPT chatbot will soon be integrated into many of its products.

Chatbots have become the latest battleground in Big Tech, with Facebook’s Meta and Google’s Alphabet both making big commitments to the development and funding of generative AI: algorithms capable of creating art, audio, text and videos from simple prompts. Current systems work by consuming vast troves of human-created content, before using super-human pattern recognition to generate unique works of their own.

ChatGPT is the first truly mainstream demonstration of this technology, attracting more than a million users within the first five days of its release in November, and receiving more online searches last month than Donald Trump, Elon Musk and bitcoin combined. It has been used to write poetry, pass university exams and develop apps, with Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella claiming that “everyone, no matter their profession” could soon use the tech “for everything they do”.

Yet despite ChatGPT’s popularity and promise, OpenAI’s rivals have so far been reluctant to release their own versions. In an apparent effort to avoid a repeat of the Tay bot debacle, any chatbots launched by major firms in recent years have been deliberately and severely restricted, like the clipping of a bird’s wings. When Facebook unveiled its own chatbot called Blenderbot last summer, there was virtually no interest. “The reason it was boring was because it was made safe,” said Meta’s chief AI scientist Yann LeCun at a forum in January. (Even with those safety checks, it still ended up making racist comments).

(Twitter/ Screengrab)

Some of the concern is not just about what such AI systems say, but how they say it. ChatGPT’s tone tends to be decisive and confident – even when it is wildly wrong. It means that it will answer questions , which could be dangerous if used on more mainstream platforms that people rely on widely, such as Google.

Beyond the reputational risk of a rogue AI, these companies also face the Innovator’s Dilemma, whereby any significant technological advancement could undermine their existing business models. If, for example, Google is able to answer questions using an AI rather than its current, traditional search tools then the latter, very profitable business could go defunct.

But the vast potential of generative AI means that if they wait too late, they could be left behind. The founder of Gmail warns artificial intelligence like ChatGPT could make search engines obsolete in the same way Google made Yellow Pages redundant. “Google may be only a year or two away from total disruption,” he wrote in December. “AI will eliminate the search engine result page, which is where they make most of their money. Even if they catch up on AI, they can’t fully deploy it without destroying the most valuable part of their business.”

The way he envisions this happening is that the AI acts like a “human researcher”, instantly combing through all the results thrown up by traditional search engines in order to sculpt the perfect response for the user.

Microsoft is already planning to integrate OpenAI’s technology in an effort to transform its search engine business, seeing an opportunity to obliterate the market dominance enjoyed by Google for more than a decade. It is an area that is prime for disruption, according to technologist Can Duruk, who wrote in a recent newsletter that Google’s “once-incredible search experience” had degenerated into a “spam-ridden, SEO-fueled hellscape”.

Google boss Sundar Pichai has already issued a “code red” to divert resources towards developing and releasing its own AI, with Alphabet reportedly planning to launch 20 new artificial intelligence products this year, including a souped-up version of its search engine.

The US tech giants are not just racing each other, they’re also racing China. A recent report by the US National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence stated: “China has the power, talent, and ambition to overtake the United States as the world leader in AI in the next decade if current dynamics don’t change.”

But changing these dynamics – of caution over competition – could exacerbate the dangerous outcomes that futurists have been warning about for decades. Some fear that the release of ChatGPT may trigger an AI arms race “to the bottom”, while security experts claim there could be an explosion of cyber crime and misinformation. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said in a recent interview that the thing that scared him most was an out-of-control plague of deepfakes. “I definitely have been watching with great concern the revenge porn generation that’s been happening with the open source image generators,” Altman said. “I think that’s causing huge and predictable harm.”

ChatGPT’s response to a question about the risks of artificial intelligence (OpenAI)

Then there’s the impact on the overall economy, with one commentator telling The Independent that they predicted ChatGPT alone had the potential to replace 20 per cent of the workforce without any further development.

Human labour has long been vulnerable to automation, but this is the first time it could also happen for human creativity. “We’ve gotten used to the idea that technological advances lead to the loss of blue-collar jobs, but now the prospect that white-collar jobs could be lost is quite disturbing,” Nicole Sahin, who heads global recruitment platform G-P, said at Davos last month. “The impacts are quite unpredictable. But what’s clear is that everything is accelerating at the speed of light.”

Even if people don’t lose their jobs directly to AI, they will almost certainly lose their jobs to people who know how to use AI. Dr Andrew Rogoyski, from the Institute for People-Centred AI at the University of Surrey, believes there is an urgent need for serious debate around the governance of AI, and not just in the context of “killer robots” that he claims distract from the more nuanced use cases of powerful artificial intelligence.

“The publicity surrounding AI systems like ChatGPT has highlighted the potential for AI to be usefully applied in areas of human endeavour,” Dr Rogoyski tells The Independent. “It brings to the foreground the need to talk about AI, how it should be governed, what we should and shouldn’t be allowed to do with it, how we gain international consensus on its use, and how we keep humans ‘in the loop’ to ensure that AI is used to benefit, not harm, humankind.”

OpenAI’s Dall-E image generator created this with the prompt ‘A robot artist painting a futuristic robot' (The Independent)

The year that Tay was released, Google’s DeepMind AI division proposed an “off switch” for rogue AI in the event that it surpasses human intelligence and ignores conventional turn-off commands. “It may be necessary for a human operator to press the big red button to prevent the agent from continuing a harmful sequence of actions,” DeepMind researchers wrote in a peer-reviewed paper titled ‘Safety Interruptible Agents’. Including this “big red button” in all advanced artificial intelligence, they claimed, was the only way of avoiding an AI apocalypse.

This outcome is something thousands of AI and robotics researchers warned about in an open letter in 2016, whose signatories included Professor Stephen Hawking. The late physicist claimed that the creation of powerful artificial intelligence would be “either the best, or the worst thing, ever to happen to humanity”. The hype at the time meant that a general consensus formed that frameworks need to be put in place and rules set to avoid the worst outcomes.

Silicon Valley appeared to collectively ditch its ethos of ‘move fast and break things’ when it came to AI, as it no longer seemed to apply when what could be broken was entire industries, the economy, or society. The release of ChatGPT may have ruptured this detente, with its launch coming after OpenAI switched from a non-profit aimed at developing friendly AI, to a for-profit firm intent on achieving artificial general intelligence (AGI) that matches or surpasses human intellect.

OpenAI is part of a wave of well-funded startups in the space – including AnthropicAI, Cohere, Adept, Neeva, Stable Diffusion and Inflection.AI – that don’t need to worry about the financial and reputational risks that come with releasing powerful but unpredictable AI to the public.

One of the best ways to train AI is to make it public, as it allows developers to discover dangers they hadn’t previously foreseen, while also allowing the systems to improve through reinforcement learning from human feedback. But these unpredictable outcomes could result in irreversible damage. The safety checks put in place by OpenAI have already been exploited by users, with Reddit forums sharing ways to jailbreak the technology with a prompt called DAN (Do Anything Now), which encourages ChatGPT to inhabit a sort of character that is free of the restrictions put in by its engineers.

Rules are needed to police this emerging space, but regulations are always lagging behind the relentless progress of technology. In the case of AI, it is way behind. The US government is currently in the “making voluntary recommendations” stage, while the UK is in the early stages of an inquiry into a proposed “pro-innovation framework for regulating AI”. This week, an Australian MP called for an inquiry into the risks of artificial intelligence after claiming it could be used for “mass destruction” – in a speech part written by ChatGPT.

Social media offers a good example of what happens when there is a lack of rules and oversight with a new technology. After the initial buzz and excitement came a wave of new problems, which included misinformation on a scale never before seen, hate speech, harassment and scams – many of which are now being recycled in some of the tamer warnings about AI.

Online search interest in the term ‘artificial intelligence’ (Google Trends)

DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis describes AI as an “epoch-defining technology, like the internet or fire or electricity”. If it is as big as the electricity revolution, then predicting what comes next is almost unfathomable – what Thomas Edison referred to as “the field of fields… it holds the secrets which will reorganise the life of the world.”

ChatGPT may be the first properly mainstream form of generative AI, demonstrating that the technology has finally reached the ‘Plateau of Productivity’, but its arrival will almost certainly accelerate the roll-out and development of already-unpredictable AI. OpenAI boss Sam Altman says the next version of ChatGPT – set to be called GPT-4 – will make its predecessor “look like a boring toy”. What comes next may be uncertain, but whatever it is will almost certainly come quickly.

Those developing AI claim that it will not just fix the bad things, but create new things to push forward progress. But this could mean destroying a lot of other things along the way. AI will force us to reinvent the way we learn, the way we work and the way we create. Laws will have to be rewritten, entire curriculums scrapped, and even economic systems rethought – Altman claims the arrival of AGI could “break capitalism”.

If it really does go badly, it won’t be a case of simply issuing an apology like when Tay bot went rogue. That same year, Altman revealed that he had a plan if the AI apocalypse arrives, admitting in an interview that he is a doomsday prepper. “I try not to think of it too much,” he said. “But I have guns, gold, potassium iodide, antibiotics, batteries, water, gas masks from the Israeli Defence Force, and a big patch of land in Big Sur I can fly to.”

“The publicity surrounding AI systems like ChatGPT has highlighted the potential for AI to be usefully applied in areas of human endeavour,” Dr Rogoyski tells The Independent. “It brings to the foreground the need to talk about AI, how it should be governed, what we should and shouldn’t be allowed to do with it, how we gain international consensus on its use, and how we keep humans ‘in the loop’ to ensure that AI is used to benefit, not harm, humankind.”

OpenAI’s Dall-E image generator created this with the prompt ‘A robot artist painting a futuristic robot' (The Independent)

The year that Tay was released, Google’s DeepMind AI division proposed an “off switch” for rogue AI in the event that it surpasses human intelligence and ignores conventional turn-off commands. “It may be necessary for a human operator to press the big red button to prevent the agent from continuing a harmful sequence of actions,” DeepMind researchers wrote in a peer-reviewed paper titled ‘Safety Interruptible Agents’. Including this “big red button” in all advanced artificial intelligence, they claimed, was the only way of avoiding an AI apocalypse.

This outcome is something thousands of AI and robotics researchers warned about in an open letter in 2016, whose signatories included Professor Stephen Hawking. The late physicist claimed that the creation of powerful artificial intelligence would be “either the best, or the worst thing, ever to happen to humanity”. The hype at the time meant that a general consensus formed that frameworks need to be put in place and rules set to avoid the worst outcomes.

Silicon Valley appeared to collectively ditch its ethos of ‘move fast and break things’ when it came to AI, as it no longer seemed to apply when what could be broken was entire industries, the economy, or society. The release of ChatGPT may have ruptured this detente, with its launch coming after OpenAI switched from a non-profit aimed at developing friendly AI, to a for-profit firm intent on achieving artificial general intelligence (AGI) that matches or surpasses human intellect.

OpenAI is part of a wave of well-funded startups in the space – including AnthropicAI, Cohere, Adept, Neeva, Stable Diffusion and Inflection.AI – that don’t need to worry about the financial and reputational risks that come with releasing powerful but unpredictable AI to the public.

One of the best ways to train AI is to make it public, as it allows developers to discover dangers they hadn’t previously foreseen, while also allowing the systems to improve through reinforcement learning from human feedback. But these unpredictable outcomes could result in irreversible damage. The safety checks put in place by OpenAI have already been exploited by users, with Reddit forums sharing ways to jailbreak the technology with a prompt called DAN (Do Anything Now), which encourages ChatGPT to inhabit a sort of character that is free of the restrictions put in by its engineers.

Rules are needed to police this emerging space, but regulations are always lagging behind the relentless progress of technology. In the case of AI, it is way behind. The US government is currently in the “making voluntary recommendations” stage, while the UK is in the early stages of an inquiry into a proposed “pro-innovation framework for regulating AI”. This week, an Australian MP called for an inquiry into the risks of artificial intelligence after claiming it could be used for “mass destruction” – in a speech part written by ChatGPT.

Social media offers a good example of what happens when there is a lack of rules and oversight with a new technology. After the initial buzz and excitement came a wave of new problems, which included misinformation on a scale never before seen, hate speech, harassment and scams – many of which are now being recycled in some of the tamer warnings about AI.

Online search interest in the term ‘artificial intelligence’ (Google Trends)

DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis describes AI as an “epoch-defining technology, like the internet or fire or electricity”. If it is as big as the electricity revolution, then predicting what comes next is almost unfathomable – what Thomas Edison referred to as “the field of fields… it holds the secrets which will reorganise the life of the world.”

ChatGPT may be the first properly mainstream form of generative AI, demonstrating that the technology has finally reached the ‘Plateau of Productivity’, but its arrival will almost certainly accelerate the roll-out and development of already-unpredictable AI. OpenAI boss Sam Altman says the next version of ChatGPT – set to be called GPT-4 – will make its predecessor “look like a boring toy”. What comes next may be uncertain, but whatever it is will almost certainly come quickly.

Those developing AI claim that it will not just fix the bad things, but create new things to push forward progress. But this could mean destroying a lot of other things along the way. AI will force us to reinvent the way we learn, the way we work and the way we create. Laws will have to be rewritten, entire curriculums scrapped, and even economic systems rethought – Altman claims the arrival of AGI could “break capitalism”.

If it really does go badly, it won’t be a case of simply issuing an apology like when Tay bot went rogue. That same year, Altman revealed that he had a plan if the AI apocalypse arrives, admitting in an interview that he is a doomsday prepper. “I try not to think of it too much,” he said. “But I have guns, gold, potassium iodide, antibiotics, batteries, water, gas masks from the Israeli Defence Force, and a big patch of land in Big Sur I can fly to.”