Paris to ban single-use plastic at 2024 Olympic Games

Reuters

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo said on Friday the city planned to ban single-use plastic when it holds the 2024 Olympic Games as part of efforts to tackle a global plastic pollution crisis.

"We have decided to make the Olympic Games the first major major event without single-use plastic," Hidalgo told a press conference at a session of the International Forum of Mayors against Plastic Pollution.

Visitors to temporary Olympics competition sites in the French capital will be admitted only without plastic bottles.

Coca-Cola KO.N, the American beverage giant and designated sponsor of the Paris Olympics, will distribute its products in re-usable glass bottles and more than 200 soda fountains, which will be redeployed after the games.

Re-usable cups will also be used for refreshments during the Olympics marathon.

"Plastic (waste) remains a major global issue: each year, 14,000 mammals and 1.4 million seabirds are killed due to the ingestion of plastic waste," Hidalgo's office said in a statement announcing the Olympics single-use plastic ban

Organisers of the Paris Olympics have said they want to halve the carbon footprint compared to previous Summer Games in Rio in 2016 and London in 2012. The Tokyo Olympics last year took place behind closed doors due to the COVID pandemic.

The U.N. Environment Programme issued a report on May 16 saying countries could reduce plastic pollution by 80% by 2040 using existing technologies and making major policy changes.

UNEP released its analysis of policy options to tackle the crisis two weeks before countries convene in Paris to launch a second round of negotiations to craft a global treaty aimed at eliminating plastic waste.

'We abuse plastic, it's so cheap': UN Environment chief

Humanity uses and abuses hundreds of millions of tonnes of plastic a year because "it's so cheap", despite the huge cost of the pollution it creates, the head of the UN Environment Programme told AFP.

Inger Andersen, an economist by training, told AFP she that a binding, "ambitious" global treaty would help fix the problem, ahead of the second round of UN-led negotiations that diplomats from 175 nations aim to conclude next year.

The interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

Q: What are the main obstacles to an ambitious treaty?

A: Today, virgin raw polymer is cheaper than recycled polymer. So here's the question: What will allow us move from that linear 'we take it, we make it, we waste it' reality to a circular approach? Right now, it's so inexpensive you can just throw plastic away. But the cost to the environment and human health is huge, and it is not taxed anywhere.

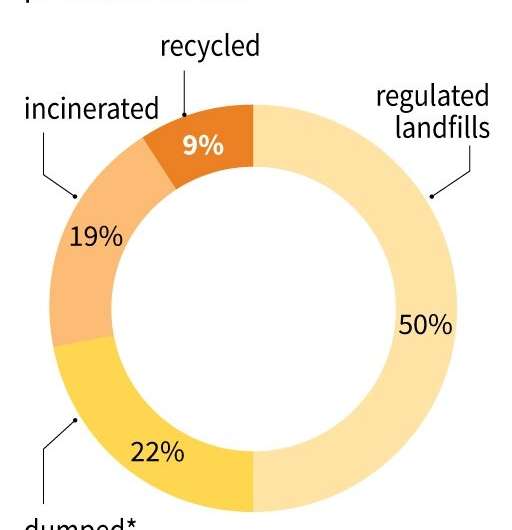

Q: Less than 10% of plastic is recycled today—is that a credible solution?

A: We can't recycle our way out of this mess. But recycling is one of the many keys that we will need to make this work. Today, we simply throw plastic away because it has no value.

When I was a little girl growing up in Denmark with very limited pocket money, my brothers and I collected plastic bottles every Saturday because we could get two krone. It wasn't much, but it made it worthwhile. Now imagine the day that this stuff has value—we would think about and treat that garbage very differently!

Q: What changes in attitude or mentality do you think we need to see?

A: Awareness is step one. Which is not to say the burden falls entirely on consumers—at the end of the day, it's business and governments that have to take that responsibility.

But every consumer has a choice. Let's say we have a party. Do we need single-use cups and plastic bags? If that bag I use to carry home five tomatoes is a heavy polymer, it will sit in a landfill for hundreds of years, maybe a thousand. Why are supermarket bananas in a plastic bag? Nature already delivered them with their own packaging.

So there are choices we can make. Children get it, and are already holding their parents to account. But the bigger system shifts will come from agreements such as the one we are negotiating.

Message to business: 'lean into it'

Q: Plastic pollution has not been a priority on the international agenda until quite recently. What changed?

A: The popular demand for solutions has become powerful, and it's coming across the board from left to right in most countries. I put it down to activism across a broad spectrum, and I am very, very grateful. I ask all those activists to keep the heat on to ensure that the treaty had ambitious and binding elements.

Q: Many green groups are worried that the plastics industry will have an undue influence in the talks.

A: For this second round of negotiations we have 2,800 participants—908 from government and 1,712 from non-government organisations (NGOs). There are ten industry associations represented. They have a role to play.

Take ozone, which is probably our most successful treaty. We couldn't find a solution to the manufactured gases depleting the ozone layer without having industry at the table.

Here's what I say to business: this is coming to a movie theatre near you soon. You might as well lean into it and be part of the change, because we will get a treaty and it will be ambitious. Once we make the enabling legislation, business will follow.

Q: Can the world do without plastics at all?

A: Plastic is everywhere. We're still going to need light switches, steering wheels, metro seats, whatever. But we need to think about the single-use dimension.

We are abusing plastic because it's so cheap. But this has consequences in the environment, in the oceans, to our health.

© 2023 AFP

Squinting in the bright light of a hot summer morning, Vu Thi Thinh perches on the edge of her small wooden boat and plucks a polystyrene block from the calm waters of Vietnam's Ha Long Bay.

It's not yet 9 am, but a mound of styrofoam buoys, plastic bottles and beer cans sit behind her.

They are the most visible sign of the human impacts that have degraded the UNESCO World Heritage Site, famed for its brilliant turquoise waters dotted with towering rainforest-topped limestone islands.

"I feel very tired because I collect trash on the bay all day without much rest," said Thinh, 50, who has been working for close to a decade as a trash picker.

"I have to make five to seven trips on the boat every day to collect it all."

Since the beginning of March, 10,000 cubic metres of rubbish—enough to fill four Olympic swimming pools—have been collected from the water, according to the Ha Long Bay management board.

The trash problem has been particularly acute over the past two months, as a scheme to replace styrofoam buoys at fish farms with more sustainable alternatives backfired and fishermen chucked their redundant polystyrene into the sea.

Authorities ordered 20 barges, eight boats and a team of dozens of people to launch a clean-up, state media said.

Do Tien Thanh, a conservationist at the Ha Long Bay Management Department, said the buoys were a short-term issue but admitted: "Ha Long Bay... is under pressure".

—Human waste—

More than seven million visitors came to visit the spectacular limestone karsts of Ha Long Bay, on Vietnam's northeastern coast, in 2022.

Authorities hope that number will jump to eight and a half million this year.

But the site's popularity, and the subsequent rapid growth of Ha Long City—which is now home to a cable car, amusement park, luxury hotels and thousands of new homes—have severely damaged its ecosystem.

Conservationists estimate there were originally around 234 types of coral in the bay—now the number is around half.

There have been signs of recovery in the past decade, with coral coverage slowly increasing again and dolphins—pushed out of the bay a decade ago—coming back in small numbers, as a ban on fishing in the core parts of the heritage site expanded their food source.

But the waste, both plastic and human, is still a huge concern.

"There are so many big residential areas near Ha Long Bay," said conservationist Thanh.

"The domestic waste from these areas, if not dealt with properly, greatly impacts the ecological system, which includes the coral reefs.

"Ha Long City can now handle just over 40 percent of its wastewater."

Single-use plastic is now banned on tourist boats, and the Ha Long Bay management board says general plastic use on board is down 90 percent from its peak.

But trash generated onshore still lines parts of the beach, with a team of rubbish collectors not able to block the eyesore from tourists.

'Plastic pollution crisis'

Pham Van Tu, a local resident and freelance tour guide, said he had received a lot of complaints from visitors.

"They read in the media that Ha Long Bay is beautiful, but when they saw a lot of floating trash, they didn't want to swim or go canoeing and they hesitated to tell their friends and family to visit," he said.

Rapid economic growth, urbanisation and changing lifestyles in communist Vietnam have led to a "plastic pollution crisis", according to the World Bank.

A report in 2022 estimated 3.1 million tonnes of plastic waste are generated every year, with at least 10 percent leaking into the waterways, making Vietnam one of the top five plastic polluters of the world's oceans.

The volume of leakage could more than double by 2030, the World Bank warns.

Larissa Helfer, 21, who travelled to Vietnam from her home in Germany, said Ha Long Bay was beautiful but the trash problem would be one of her strongest memories of the trip.

"Normally you (might say) 'Look at the view! Look at the fishing villages!" she told AFP.

But here "you have to talk about the trash, (you say) 'oh god... look at the plastic bottles and things in the sea.' And it makes you sad."

Thinh, the trash collector, grew up in Ha Long and remembers a very different bay.

"It didn't look so terrible," she said.

"Of course, a lot of work makes me tired and irritated," she admitted. "But we must do our work."

© 2023 AFP

Explore further Trash for tickets on Indonesia's 'plastic bus'