DIANE JEANTET

Wed, December 13, 2023

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — The renowned chief from the Amazon rainforest and the Belgian filmmaker appeared to be close friends at this year's Cannes Film Festival. Far from the flashing cameras, however, their decades-long partnership was nearing its end.

With his feathered crown and wooden lip plate, Chief Raoni of the Kayapo tribe is instantly recognizable the world over. He has met with presidents, royals and celebrities to raise funds for Brazil’s Indigenous peoples and to protect their lands. Almost always in the background was a less familiar face, that of Jean-Pierre Dutilleux, whose documentary about Raoni was a 1979 Oscar nominee. In the years since, he has acted as Raoni's gatekeeper abroad and brokered meetings with leaders and luminaries. But many Kayapo and others who crossed Dutilleux's path harbored growing suspicions about him.

The Associated Press interviewed dozens of people over nearly a year — including both Raoni and Dutilleux — to provide an inside look at the falling out and what it signals about efforts to preserve the Amazon.

HOW DID THEY RAISE MONEY?

The two repeatedly traveled to Europe, meeting with leaders including French Presidents Jacques Chirac and Emmanuel Macron, Leonardo DiCaprio, Monaco’s Prince Albert II, the Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg and even Pope Francis. At each of those encounters, they sought contributions to help Raoni's people and other Indigenous groups in the Amazon — and secured pledges for hundreds of thousands of dollars over the years. They also hosted galas, charity dinners and auctions for private donors.

Dutilleux launched the Rainforest Foundation with music legend Sting, who put down his guitar to travel the world with Raoni and Dutilleux to spotlight the plight of Indigenous people. Their efforts largely contributed to the Brazilian government’s recognition -– and, theoretically, protection -– of the Menkragnoti Indigenous Territory, an area of 5 million hectares (19,000 square miles). Several films and books about the Indigenous chief, including one about their tour with Sting, yielded royalties. Dutilleux also raised money in Raoni’s name through Association Forêt Vierge, one of the several non-profit groups created to receive donations during his tour with Sting.

WHAT ARE THE ACCUSATIONS?

The tribal leader, two other members of his non-profit group, the Raoni Institute, and Raoni’s future successor as leader of the tribe all said Dutilleux over the last two decades repeatedly promised them large sums of money to fund social projects but only delivered a fraction of it. They said he also refused to be transparent about money raised in Raoni’s name on their tours of Europe, or from his books and films about the Kayapo.

“My name is used to raise money,” Raoni told The Associated Press in an interview in Brasilia. “But Jean-Pierre doesn’t give me much.”

Others who have come to work with Dutilleux in the Amazon over the years have also expressed concerns about the filmmaker's relationship with Raoni. In interviews with the AP, many have complained about his lack of transparency when it came to raising funds for Indigenous peoples.

Some directly suffered from it, including Spanish photographer Alexis de Vilar, whose non-profit group was in charge of organizing a charity gala for the U.S. premiere of Dutilleux's “Raoni” documentary in 1979. The funds were supposed to go to Indigenous peoples in Brazil and the U.S. Dutilleux had been in charge of collecting money from ticket sales for the event, but never turned over any amount, de Vilar said. “There was no money, not even to build a school,” de Vilar said.

Sting accused Dutilleux in 1990 of keeping all royalties from the book about their tour, rather than giving them to the Rainforest Foundation as was promised on the book’s cover. As a result, the Rainforest Foundation removed him as a trustee.

HOW MUCH OF THE TOTAL RAISED WAS PROVIDED TO INDIGENOUS PEOPLE?

AP was not able to determine the amount of money raised over the last five decades.

Association Forêt Vierge president Robert Dardanne told the AP that the group gave the Raoni Institute all the money that it was owed. The organization provided records indicating it sent 14,200 euros ($15,300) after a 2011 fund-raising trip and a little over 80,000 euros ($86,000) after a 2019 campaign. But it did not supply records for at least four previous campaigns, saying that under French law it was only required to retain such records for a decade.

Raoni and others close to him say these amounts pale in comparison with the millions of dollars that Dutilleux has repeatedly promised them.

Dardanne said he believed a lack of communication between the chief and the Raoni Institute was at the root of the chief’s discontent. “There is sometimes a gap between the expectations of Indigenous communities and reality,” he said.

WHAT DOES DUTILLEUX SAY?

Dutilleux told the AP that he never had access to the money raised and denied Raoni's claims that he had failed to deliver.

“He can sometimes say things like that, it has to do with age. Maybe it’ll happen to me too, to say stupid things," Dutilleux, now 74, said in an interview in Paris. “I want nothing to do with money. It doesn’t interest me. I’m a filmmaker, I’m an artist. I’m not an accountant.”

He maintains that the gala in Mann’s Chinese Theatre did not generate any profit and said his relationship with Sting had broken down due to their “different visions,” without elaborating.

Dutilleux said criticism of his legacy in the Amazon involved "three or four people" who were trying to take him down. The AP spoke to more than two dozen people for this story.

WHY DID RAONI KEEP FUNDRAISING WITH DUTILLEUX FOR SO LONG?

Despite the Kayapo’s suspicions that stretch back nearly 20 years, Raoni’s inner circle believed he could not abandon Dutilleux. It was a decision, they said, rooted in the centuries-old power imbalance that exists when an Indigenous tribe partners with an influential white man. In short, Raoni needed help from someone — anyone — for preservation of the Amazon, and Dutilleux was willing and able to open doors to international donors.

“He sees far beyond petty quarrels between egos and clans,” said French environmentalist Philippe Barre, who has worked with Raoni in the past. “What matters to him is that the important subjects emerge … even if some feather their own nests in the process.”

DIANE JEANTET

Wed, December 13, 2023

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — It was considered to be among the world’s most productive partnerships between an Indigenous chief and a Westerner.

For five decades, the Amazonian tribal leader and Belgian film director enlisted presidents and royals, even Pope Francis, to improve the lives of Brazil’s Indigenous peoples and protect their lands. The pair befriended celebrities and movie stars. Sting, the musical legend, was one of their greatest champions.

Just a few months ago, their bond seemed as strong as ever. Chief Raoni Metuktire, sporting his iconic lip plate and an emerald feathered crown, and tuxedo-clad filmmaker Jean-Pierre Dutilleux were at the Cannes Film Festival to promote the Belgian’s latest documentary: “Raoni: An Unusual Friendship.” Standing on the red carpet, amid a flurry of camera flashes, the two clasped hands, as if old friends.

Behind the scenes, however, the relationship was nearing its end. Not long after returning to Brazil in May, the chief of the Kayapo severed ties with his Belgian acolyte.

Raoni and those closest to him told The Associated Press they had long distrusted Dutilleux, suspecting the filmmaker of failing to deliver funds raised for the Kayapo. They also accused Dutilleux of exploiting the chief’s image and reputation to enhance his influence and film career.

“My name is used to raise money,” Raoni said in an interview with AP in Brasilia. “But Jean-Pierre doesn’t give me much.”

The tribal leader, two other members of his non-profit group, the Raoni Institute, and Raoni’s successor all said Dutilleux repeatedly pledged to give them large sums of money to fund social projects but only delivered a fraction of it. They said he also refused to be transparent about money raised in Raoni’s name on their tours of Europe, or from his books and films about the Kayapo.

Dutilleux denied any wrongdoing, repeating that he never had access to the money.

“He can sometimes say things like that, it has to do with age. Maybe it’ll happen to me too, to say stupid things," Dutilleux, now 74, told the AP in an interview in Paris, adding that money “doesn’t interest me. I’m a filmmaker, I’m an artist. I’m not an accountant.”

Despite the Kayapo’s long-running suspicions, which stretch back nearly 20 years, Raoni’s inner circle believed he could not abandon Dutilleux. It was a decision, they said, rooted in the centuries-old power imbalance that exists when an Indigenous tribe partners with an influential “kuben,” the Kayapo word for white man.

THE CHIEF

Raoni was born sometime in the 1930s — nobody knows the precise year — in the Metuktire branch of the Kayapo tribe. By then, the first Amazon rubber boom had ended after nearly three decades of often brutal exploitation of Indigenous populations.

His family and tribe members were semi-nomadic and spent their days hunting and fishing in the basin of the Amazon’s Xingu River, an area the size of France and home to dozens of Indigenous groups.

Their first contact with kubens was in 1954. By then, Raoni was a charismatic warrior and shaman, respected for his political acumen and bravery in combat against rival tribes and those seeking to exploit their resources.

He learned to speak Portuguese — but not to read or write — and became his tribe’s main interlocutor with the outside world, as well as a leading voice in the protection of Indigenous rights in Brazil.

By the 1970s, Indigenous peoples were under increasing pressure from Brazil’s military dictatorship, which in an effort to develop the Amazon constructed highways, sponsored colonization programs and offered generous subsidies to farmers. Raoni and others were doing everything they could to halt the destruction of their ancestral lands.

That’s also about when Raoni saved Dutilleux’s life.

THE FILMMAKER

Born into a bourgeois family in a provincial town in Belgium, Dutilleux dreamed of distant landscapes, and at 22 took off for Brazil, where he would direct an ethnographic film about Indigenous tribes in the Amazon rainforest.

There, a group of Kayapo tribesmen mistook him for a highway construction worker who typically brought death and disease to the region and threatened to kill him. Raoni stepped in to prevent any violence, and the two men became friends.

A few years later, Dutilleux returned to the Xingu to shoot a documentary focusing on the shaman. Dutilleux convinced Marlon Brando to narrate the American version, which was a 1979 Oscar nominee. The film’s success turned Raoni into one of the leading figures among Indigenous peoples, and Dutilleux became his gatekeeper.

Almost right away, some advocates and Kayapo leaders were concerned that Dutilleux was more interested in profiting off Raoni than in helping the Indigenous cause.

One of those who was suspicious of Dutilleux is Alexis de Vilar, a Spanish photographer who founded the Tribal Life Fund, a non-profit group dedicated to the protection of Indigenous peoples.

The Tribal Life Fund sponsored the documentary’s U.S. premiere with a gala at Mann’s Chinese Theatre, a landmark Hollywood venue. The black-tie ceremony was hosted by Jon Voight and Will Sampson, who starred in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” and it drew an A-list crowd.

“All Hollywood was there,” de Vilar recalled. With some guests spending several thousand dollars for a ticket, de Vilar expected his non-profit to collect at least $50,000, which the Tribal Life Fund had said would finance various social projects.

But the Tribal Life Fund didn't receive any of that money. Dutilleux had been in charge of collecting payments for tickets but never turned over any it, de Vilar said. “There was no money, not even to build a school,” de Vilar said.

Dutilleux maintains that the gala did not generate any profit.

THE MUSICIAN

A decade later, Dutilleux introduced the Indigenous chief to Sting, the former lead singer of The Police — an encounter that would turn Raoni into an even greater celebrity. After playing a concert in Rio de Janeiro, Sting traveled to the Amazon and became a passionate ally of Raoni and the Kayapo. He and Dutilleux launched Rainforest Foundation, a non-profit group that to this day promotes forest protection worldwide.

In 1989, Sting put down his guitar to travel the world with Raoni and Dutilleux to spotlight the plight of Indigenous people. Their efforts largely contributed to the Brazilian government’s recognition -– and, theoretically, protection -– of the Menkragnoti Indigenous Territory, an area of 5 million hectares (19,000 square miles).

Despite the victory, the trio had already fallen out.

Dutilleux was pushed out of Rainforest Foundation after Sting accused the filmmaker of trying to profit off the charity by keeping royalties from a book about their tour. According to the book’s cover, those royalties were supposed to go toward Indigenous peoples.

In his interview with the AP, Dutilleux said his relationship with Sting had broken down due to their “different visions."

Dutilleux continued to raise money in Raoni’s name through Association Forêt Vierge, one of the several non-profit groups created to receive donations during his world tour with Sting. Dutilleux served as its president from 1989 to 1999 and as “honorary president” since then.

In 1991, Dutilleux organized a campaign in Europe to raise $5 million to create a vast Brazilian national park and protect an area three times the size of Belgium.

The project, he told a Belgian newspaper, had been conceived by a director at Brazil’s Indigenous affairs agency.

But the Brazilian official, Sydney Possuelo, denied any involvement in the effort. He called Dutilleux’s plans for the park “stupid” and described the calculations as “absurd.”

Possuelo, 83, a globally respected expert on isolated tribes, told the AP he believed Dutilleux was “harmful to Indigenous peoples.”

“He is a freeloader,” he added. “To him, the Indigenous question is a business. Every time he shows up, it’s to somehow take advantage of people like Raoni.”

Raoni skipped the tour, and it’s unclear how much money Dutilleux raised. Dutilleux told the AP the campaign was called off and blamed Possuelo’s criticism for its demise.

Despite the setback, Dutilleux returned to the Xingu — “my tribal heart,” as he has described it. On his visits to Raoni and other Indigenous tribes, Dutilleux tried to engage them in new fund-raising proposals, whether a book, movie or tour.

“He’s always using him,” said Raoni’s nephew, chief Megaron Txucarramãe.

Megaron, who is likely to be Raoni’s successor, says he has repeatedly advised his uncle against teaming up with Dutilleux. “This lack of clarity, of transparency with money happens every time he travels with him,” Megaron said.

Raoni has confronted Dutilleux about the absence of payments on many occasions. In 2002, following a tour during which then-French President Jacques Chirac committed to help launch the Raoni Institute, the chief filed a petition with Brazilian prosecutors, asking that measures be taken so that the money would not be funneled through Dutilleux. The complaint went nowhere, lost in the morass of the Amazon’s overloaded judicial system.

THE DAM

The two men made peace after Dutilleux offered to write Raoni’s biography, which was published in 2010. That year and in 2011, they went on tour to promote the book and raise money for the Kayapo.

At the time, construction of the mammoth Belo Monte hydroelectric dam was underway, raising alarms in Indigenous communities over concerns it would dry up vast stretches of the Xingu River.

For decades, Raoni and other tribal leaders had aggressively fought construction of the dam, saying it would displace tens of thousands of people.

In meetings with European leaders during the 2011 campaign, however, Raoni and Dutilleux did not really discuss Belo Monte, said Christian Poirier, who was leading the non-profit Amazon Watch’s campaign to halt the construction.

Poirier, who had heard of Dutilleux’s dubious track record in the Amazon, investigated and came to believe that the chief had been provided with poor translations and kept away from anti-dam advocates, and that Dutilleux intentionally downplayed Raoni’s objections.

Even though Raoni was desperate to stop the project, Dutilleux told local reporters that it was not the focus of their tour.

In an email obtained by AP, Dutilleux wrote to members of his non-profit group that it was too risky for them to fight the dam. Criticism might harm their ability to raise funds and jeopardize a potential meeting with a powerful French energy company, he wrote.

When Raoni returned to Brazil and learned that advocates were upset he did not speak out about the dam project, he and other Kayapo leaders were furious.

They issued a statement saying Dutilleux was no longer authorized to receive donations on their behalf. They pointed out that they had received little of the money Dutilleux had promised them if Raoni accompanied him to meetings with influential people in France in 2011.

Association Forêt Vierge president Robert Dardanne told the AP that the group gave the Raoni Institute all the money it was owed. The organization provided records indicating it sent 14,200 euros ($15,300) after the 2011 fund-raising trip and a little over 80,000 euros ($86,000) after the 2019 campaign.

But it did not supply records for at least four previous campaigns, stipulating that under French law it was only required to retain such records for a decade.

Raoni and others close to him say these amounts pale in comparison of the millions that Dutilleux has repeatedly promised them.

Raoni publicly accused Dutilleux in 2016 of having tricked him into signing a document that had been poorly translated, to hamper fundraising efforts led by a rival non-profit group. The chief also accused Dutilleux of using his likeness for commercial purposes.

Dutilleux was not fazed by the allegations. In 2019, he approached Raoni and offered to broker a meeting between the chief and French President Emmanuel Macron, as well as other powerful European figures.

During the meetings, Macron agreed to give a million euros to the Raoni Institute and another tribe from the Xingu.

The Raoni Institute and others involved in talks with Macron’s representatives told the AP that government officials desperately sought alternatives to bypass Dutilleux’s group. The money was eventually sent to the Raoni Institute through the French Development Agency and the non-profit Conservation International.

THE RUPTURE

Last year, Dutilleux visited Raoni and sold him on what would be their final tour to help promote his latest documentary, promising the chief they would raise significant money for his tribe.

Raoni reluctantly accepted the pitch. The situation had become more dire in the Amazon. Illegal loggers and miners thrived under far-right President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, with deforestation rising dramatically. Even with a newly elected president who has vowed to end all illegal deforestation, an estimated 585 acres (236 hectares) of Brazil’s Amazon are being hacked away each day.

Raoni and Kayapo leaders were skeptical of Dutilleux’s promises. But those who know the chief said they were not surprised that he decided to join him in Europe.

“He sees far beyond petty quarrels between egos and clans,” said French environmentalist Philippe Barre, who has worked with Raoni in the past. “What matters to him is that the important subjects emerge … even if some feather their own nests in the process.”

Kayapo people in Raoni’s inner circle told the AP the chief is finally done with Dutilleux. As evidence, they noted he skipped the October premiere in Rio of Dutilleux’s film "Raoni: An Unusual Friendship."

In another interview with the AP that same month, Raoni spoke at length about his legacy and the people who helped his cause over the years. He could not bring himself to say the filmmaker’s name.

___

AP journalists John Leicester and Sylvie Corbet in Paris contributed to this story.

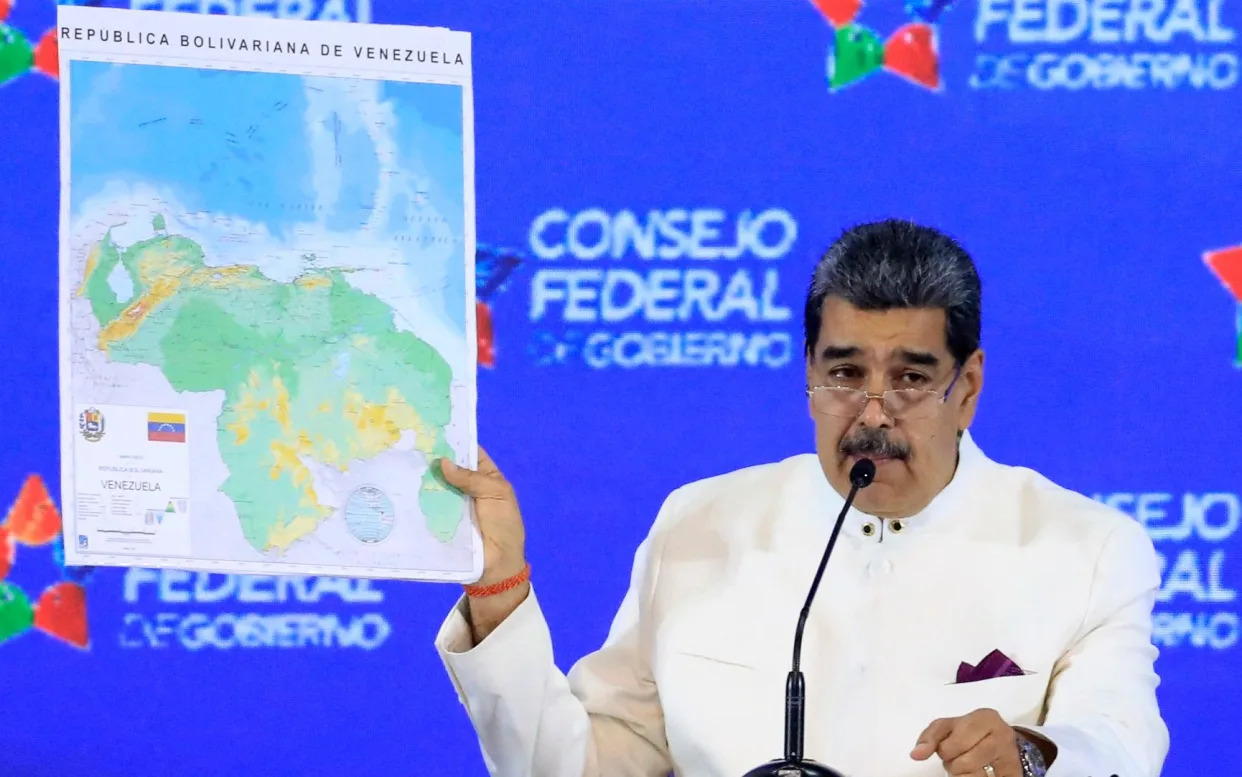

Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, right, stands next to Indigenous leader Raoni Metuktire after his swearing-in ceremony at Planalto palace in Brasilia, Brazil, Jan. 1, 2023. For five decades, the Amazonian tribal Chief Raoni Metuktire and Belgium filmmaker Jean-Pierre Dutilleux enlisted presidents and royals to improve the lives of Brazil’s Indigenous peoples and protect their lands.