Ten Victories for the U$ Working Class in

Blue Bird bus factory employee, Fort Valley, Georgia. Credit: United Steelworkers.

Looking for something positive to celebrate on New Year’s Eve? Consider lifting a glass to the hardworking people behind these inspiring victories of 2023.

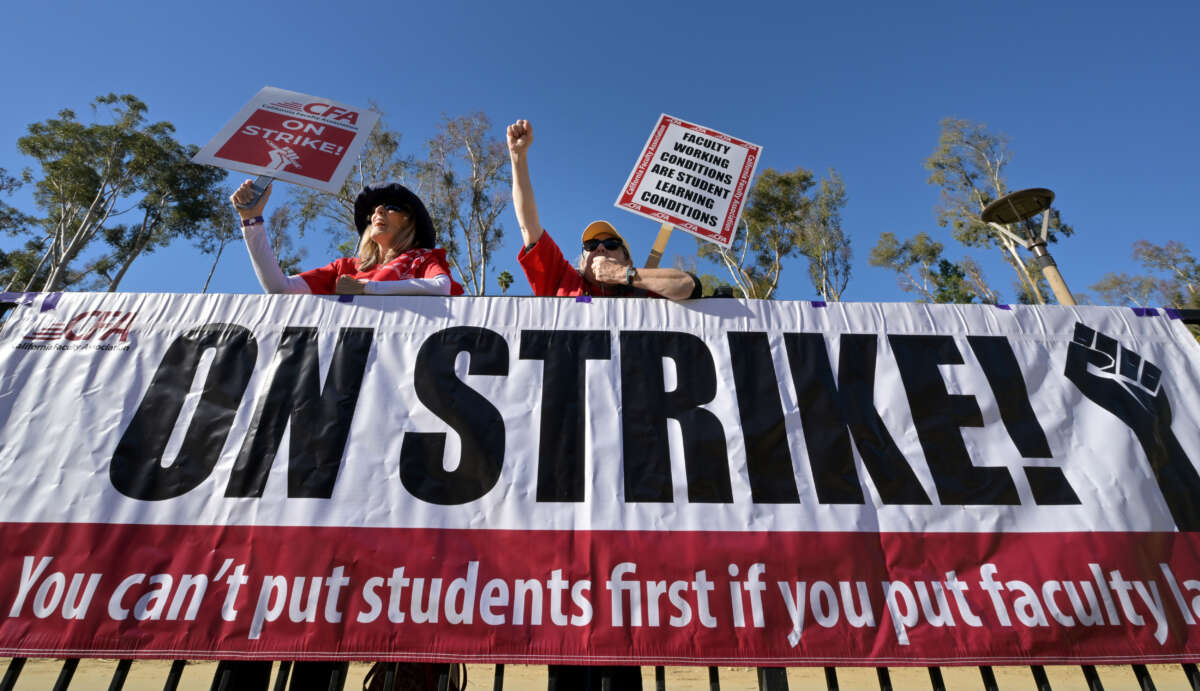

1. The ‘Year of the Strike’

More than half a million American workers walked off the job this year. In October, companies lost more workdays to strikes than in any month during the past 40 years.

Big 3 auto workers, Hollywood writers and actors, Las Vegas and Los Angeles hotel staff, and Kaiser Permanente health care employees were among those who used strikes to score big bargaining table wins. For UPS drivers, the mere threat of a Teamsters strike was enough to secure historic wage hikes and safety protections.

After renewing contracts with Ford, GM, Stellantis, and UPS, the UAW and the Teamsters doubled down on efforts to organize the unorganized. The Teamsters picketed outside 25 Amazon warehouses, demanding a fair contract for unionized drivers at a California-based delivery service for the notoriously anti-union retailer. The UAW set their sights on non-unionized car companies, causing so much indigestion among Nissan, Toyota, Honda, and Hyundai executives that they immediately hiked wages for their U.S. employees.

2. Black worker organizing in the south

To move the needle on the country’s dismally low 6 percent unionization rate, the labor movement will need to make inroads in tough territory, particularly in historically anti-union southern states that have been magnets for investment.

Two union victories in 2023 are the latest proof that this goal is not impossible. The United Steelworkers won an election at a Blue Bird bus factory in Georgia with nearly 1,500 predominantly Black workers. In three Alabama cities, AT&T Mobility workers at In Home Expert hubs joined the Communications Workers of America.

3. A crack in the anti-union tech sector

The past year also saw union progress in another historically union-averse territory: the tech sector. Earlier this month, Microsoft forged an agreement with the AFL-CIO to remain neutral in organizing drives among their U.S.-based workers. This will make it easier for about 100,000 Microsoft employees to unionize, with potential ripple effects across the industry.

4. New trifecta states

In Michigan and Minnesota, pro-worker state legislators hit the ground running after Democrats won state trifectas in 2022.

Minnesota passed a blizzard of pro-labor reforms, including paid sick leave for most workers, minimum pay and benefits for nursing home staff, and wage theft protections for construction workers. Teachers will be able to negotiate over class sizes and nurses will have a greater say in staffing levels. The new laws also ban non-compete agreements and “captive audience” meetings designed to undercut union support.

This year Michigan became the first state in six decades to roll back anti-union “right-to-work” laws. They also restored a “prevailing wage” law requiring construction contractors to pay union wages and benefits on state-funded projects.

5. Cities lead the way on low-wage worker protections

The federal minimum wage for tipped workers has been stuck at $2.13 since 1991. In that vacuum, states and cities are taking action. This year, restaurant servers and other advocates in the nation’s capital successfully beat back last-ditch industry attempts to undercut a victorious 2022 ballot initiative to phase out the local subminimum tipped wage. After a multi-year, hard-fought campaign, DC’s tipped workers got their first raise this past summer, putting them on track to earn the full local minimum wage by 2027. The Chicago City Council also passed a five-year tipped wage phaseout plan, set to begin in 2024.

App-based delivery drivers in New York City had to fight back in 2023 against Uber, DoorDash, and other corporations’ efforts to block introduction of the nation’s first minimum wage for their occupation. Gig companies finally lost their legal challenges to the pay rule in late November. Delivery driver pay rose to $17.96 an hour on December 4 and will increase to $19.96 when the legislation takes full effect in 2025.

6. College campuses as labor hotbeds

Organizing among graduate and medical students continued to explode in 2023, with the highest number of union elections among these groups than in any year since the 1990s. In the first four months of 2023 alone, over 14,000 graduate students on five campuses voted to join the United Electrical union — all by margins of over 80 percent. Campuses across the country coordinated organizing efforts through a series of teach-ins and other events under the banner of Labor Spring, an initiative that will continue in 2024.

7. Stock buyback blowback

Many of the labor battles of 2023 skewered corporate executives for underpaying workers while blowing money on stock buybacks, a financial maneuver that artificially inflates CEO stock-based pay. Two precedent-setting federal policies to rein in buybacks also took effect in 2023. For the first time, corporations faced a one percent excise tax on buybacks. The Biden administration also began giving companies a leg up in the competition for new semiconductor subsidies if they agree to forgo all stock buybacks for five years. This important precedent should be expanded to all companies receiving any form of public funds.

8. Collective bargaining requirements on federally funded construction projects

With megabillions in new public investment flowing into infrastructure projects, it’s critical that the administration ensure these taxpayer dollars support good jobs. This week, Biden officials took an important step forward by finalizing regulationsrequiring the use of “project labor agreements” between employers and workers for large federal construction projects. The terms of these pre-hire collective bargaining agreements must cover all parties — contractors, subcontractors, and unions. This important rule should be expanded beyond construction to contractors that provide goods and other services.

9. Trashing “junk” fees

Working class Americans fork out tens of billions of dollars every year on deceptive, hidden charges that raise the cost of banking and internet services, concerts and movies, rental cars and apartments, and more. In October, President Joe Biden announced a plan to put these “junk fees” where they belong — in the trash.

Under the plan, the Federal Trade Commission aims to force companies to disclose the total price of goods and services up front and slap violators with big fines. This will mean no hidden fees — and more money in working families’ pockets.

10. NLRB rulings on Amazon and Starbucks

Anyone wondering whether our labor laws need fixing need look no further than the fact that Starbucks and Amazon have been able to get away with refusing to negotiate with workers who voted to unionize for well more than a year. (Two years for the path-breaking Buffalo, New York Starbucks workers). On the positive side, Biden appointees at the National Labor Relations Board seem to be making the most of their current authority and capacity.

In August, the labor board issued a ruling that will make union-busting harder in cases where a majority of workers have signed union cards but the employer still demands an election. Under the ruling, bosses who engage in unfair labor practices in these situations will now be forced to recognize and bargain with the union without an election.

In the meantime, the NLRB is continuing to try to hold Starbucks and Amazon accountable for rampant labor rights violations. The board has 240 open or settled charges against Amazon in 26 states and they’ve issued more than 100 complaintsagainst Starbucks, covering hundreds of accusations of threats or retaliation against union supporters and failure to bargain in good faith. Most recently, the NLRB ordered the reopening of 23 Starbucks cafes, alleging the company had closed them to suppress union activity, in violation of federal law.

Reflecting on 2023, Starbucks barista and union organizer Shep Searl marveled at how diverse workers, “from Teamsters to actors,” demonstrated that there are many ways to win through collective action.

“Every day, we’ve been absorbing that information and utilizing it in our mobilization and escalation plan,” Searl told Inequality.org. “We aren’t going anywhere and so much of that is inspired by the other campaigns. If we stand together, there’s no mountain we cannot climb.”

Sarah Anderson directs the Global Economy Project at the Institute for Policy Studies.