Ed Power

Tue, 6 February 2024

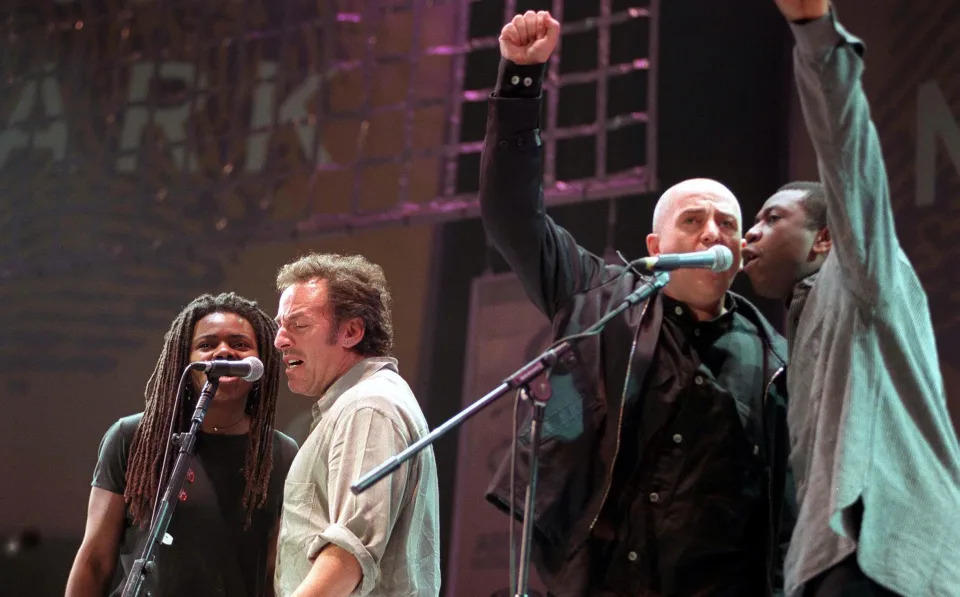

Tracy Chapman and Luke Combs perform onstage during the 66th GRAMMY Awards

- John Shearer/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

It takes a special star power to eclipse Grammy winners Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish and Miley Cyrus – not to mention a grumpy Jay-Z complaining about the lack of gongs going the way of his wife, the obscure and unheralded singer Beyoncé. But that was what 59-year-old Tracy Chapman achieved when she performed her evergreen dirge Fast Car at Sunday night’s ceremony in a duet with country artist Luke Combs.

Combs’s cover of Fast Car was a huge hit last year. But there was no doubt about who had the upper hand as he and Chapman negotiated the tune on the Grammys’ stage. Gazing at his musical partner with undisguised awe, Combs could have been a stand-in for the millions watching at home, likewise blown away by the ache of Chapman’s voice and by the searing power of lyrics that remain undimmed in their ferocity after 36 years. The impact was immediate – on the back of the Grammys, the track shot to the top of the iTunes charts.

But the biggest surprise wasn’t that Chapman remains a huge talent. It was that she was in front of the cameras in the first place. In the 16 years since her last album, Our Bright Future, she has become one of pop’s great recluses. She hasn’t quite disappeared off the face of creation – three and a half years ago, on the eve of the US Presidential election, she did her bit to topple Donald Trump by performing Talkin’ Bout A Revolution on Seth Meyers’s late-night chat show.

But she has generally maintained a discreet silence and has not toured since visiting Europe in the summer of 2009. Her last UK show, to date, was at the London Roundhouse, where her set included a version of The Cure’s Love Song. And then she was gone – off into the great unknown.

Chapman is no musical eccentric in the tradition of Brian Wilson or Syd Barrett, whose retreats from the spotlight were accompanied by psychological breakdowns of varying severity. As she has grown older, it is more accurate to say that she has come to terms with the fact she is not a crowd pleaser and does not enjoy attention.

Hugely introverted, Chapman has been content to live off the music industry grid – to the point that it is unclear where the Ohio-born artist even calls home nowadays or if she is in a relationship (in the Nineties, she and writer Alice Walker were together for a number of years).

Aside from that Seth Meyers appearance, she had surfaced just once in the run-up to the Grammys – to sue rapper Nicki Minaj for sampling without her permission the track Baby Can I Hold You Now. Chapman is opposed to having her work re-used, and the dispute was settled only when Minaj agreed to $450,000.

Otherwise, she was acoustic pop’s great mystery woman. “I’m a naturally shy person – and it was a bit unusual for me to have a job that involves being in the public,” she told me in 2008, as she was preparing to embark on the first leg of that farewell tour. “I started playing in folk clubs in Cambridge and Boston, usually in front of my friends. That made it much easier. I guess as time passed I grew into it in some ways. I started to understand the business a little better – the nature of celebrity – and tried to figure out a way for it to work.”

It takes a special star power to eclipse Grammy winners Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish and Miley Cyrus – not to mention a grumpy Jay-Z complaining about the lack of gongs going the way of his wife, the obscure and unheralded singer Beyoncé. But that was what 59-year-old Tracy Chapman achieved when she performed her evergreen dirge Fast Car at Sunday night’s ceremony in a duet with country artist Luke Combs.

Combs’s cover of Fast Car was a huge hit last year. But there was no doubt about who had the upper hand as he and Chapman negotiated the tune on the Grammys’ stage. Gazing at his musical partner with undisguised awe, Combs could have been a stand-in for the millions watching at home, likewise blown away by the ache of Chapman’s voice and by the searing power of lyrics that remain undimmed in their ferocity after 36 years. The impact was immediate – on the back of the Grammys, the track shot to the top of the iTunes charts.

But the biggest surprise wasn’t that Chapman remains a huge talent. It was that she was in front of the cameras in the first place. In the 16 years since her last album, Our Bright Future, she has become one of pop’s great recluses. She hasn’t quite disappeared off the face of creation – three and a half years ago, on the eve of the US Presidential election, she did her bit to topple Donald Trump by performing Talkin’ Bout A Revolution on Seth Meyers’s late-night chat show.

But she has generally maintained a discreet silence and has not toured since visiting Europe in the summer of 2009. Her last UK show, to date, was at the London Roundhouse, where her set included a version of The Cure’s Love Song. And then she was gone – off into the great unknown.

Chapman is no musical eccentric in the tradition of Brian Wilson or Syd Barrett, whose retreats from the spotlight were accompanied by psychological breakdowns of varying severity. As she has grown older, it is more accurate to say that she has come to terms with the fact she is not a crowd pleaser and does not enjoy attention.

Hugely introverted, Chapman has been content to live off the music industry grid – to the point that it is unclear where the Ohio-born artist even calls home nowadays or if she is in a relationship (in the Nineties, she and writer Alice Walker were together for a number of years).

Aside from that Seth Meyers appearance, she had surfaced just once in the run-up to the Grammys – to sue rapper Nicki Minaj for sampling without her permission the track Baby Can I Hold You Now. Chapman is opposed to having her work re-used, and the dispute was settled only when Minaj agreed to $450,000.

Otherwise, she was acoustic pop’s great mystery woman. “I’m a naturally shy person – and it was a bit unusual for me to have a job that involves being in the public,” she told me in 2008, as she was preparing to embark on the first leg of that farewell tour. “I started playing in folk clubs in Cambridge and Boston, usually in front of my friends. That made it much easier. I guess as time passed I grew into it in some ways. I started to understand the business a little better – the nature of celebrity – and tried to figure out a way for it to work.”

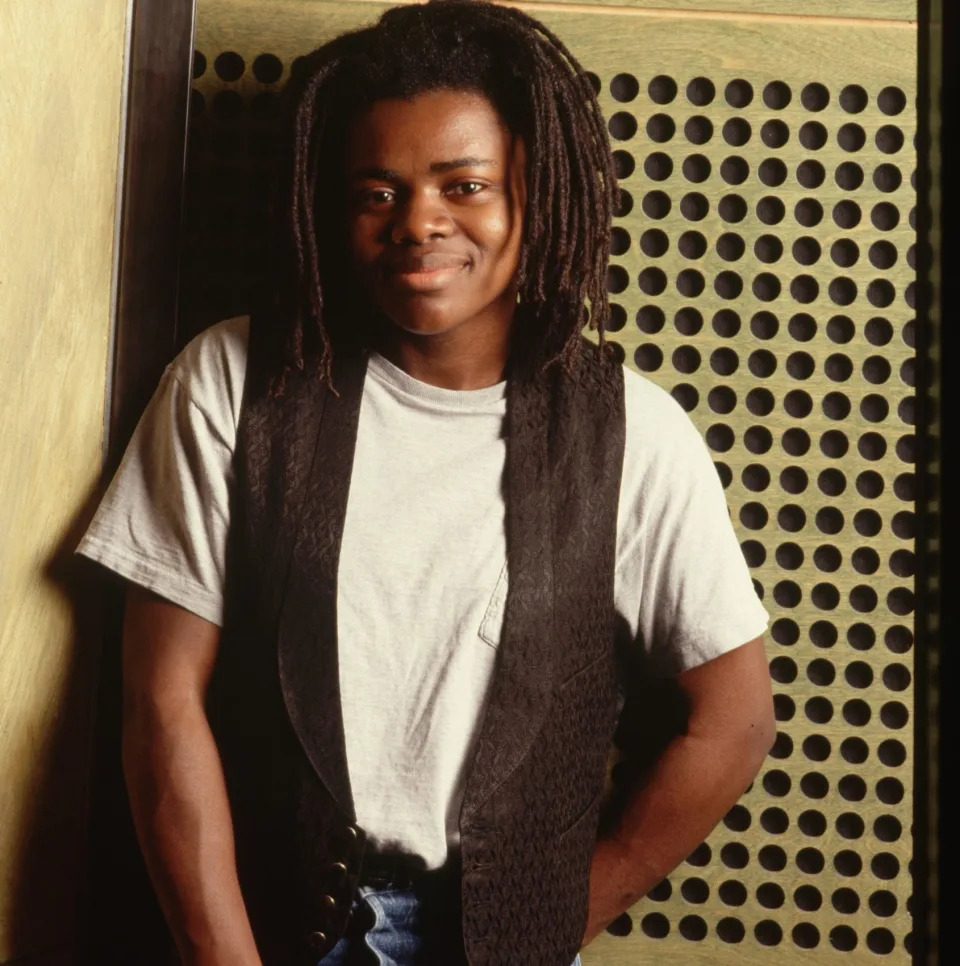

Amnesty International Charity Concert: Tracy Chapman, Bruce Springsteen, Peter Gabriel And Youssou N'Dour - Brian Rasic/Getty Images

“Figuring it out” meant making peace with the fact that, in the US, she was regarded as an anomaly: an African-American woman playing acoustic guitar. If few on this side of the Atlantic batted an eye-lid, it was an immediate talking point in the US.

“I remember people at my record label asking me why I wanted to play acoustic guitar,” she told me. “One person said to me: why aren’t you rapping? All because I was black. I used get it from my own family, too. They were perplexed by my interest in the acoustic guitar. It struck them as odd.”

It wasn’t just her family. After the release of her second album in 1989, Crossroads, Public Enemy’s Chuck D declared, “black people cannot feel Tracy Chapman”. Still, America’s racial schisms notwithstanding, she made a profound impact on the singer-songwriter genre. That is largely – though not entirely – down to the magisterial Fast Car, a downbeat ballad that makes the listener feel seven feet tall.

The tune has its origins in her working-class upbringing in Cleveland. “It very generally represents the world that I saw when I was growing up and Cleveland, Ohio, coming from a working-class background, being raised by a single mom and being in a community of people who were struggling,” she told the BBC. “Everyone was working hard and hoping that things would get better.”

Fast Car is highly symbolic. While the narrator sings about getting out of town in a hot set of wheels, that is just a metaphor for her desire for escape – Chapman isn’t auditioning for a presenter’s gig on Top Gear. “I never had a fast car,” said Chapman. “It’s a story about a couple and how they are trying to make a life together and they face various challenges.”

She wrote it while studying at Tufts University in Boston. One of her fellow students, Brian Koppelman, was the son of music publisher Charles Koppelman (Brian later became a screenwriter – penning Rounders and Ocean’s 13). Passed a tape of Fast Car, Charles was blown away by her talent. He signed her to a management deal – and immediately contacted Elektra Records.

As Chapman would recall, executives were initially nonplussed at the sight of a young black woman with a guitar. Still, they smelled a hit and paired Champan with Joan Baez / Joe Jackson producer David Kershenbaum, who worked with her on the studio version of Fast Car

Tracy Chapman in 1992 - Getty

For all its promise, the track failed to cause a stir on its release in April 1988. Everything changed that June when Chapman appeared at Wembley for a birthday concert in honour of Nelson Mandela. As with the Grammys, it was packed with stars: Whitney Houston, Peter Gabriel and Jackson Browne. Nobody expected Chapman to outshine them.

She performed a three-song set – but did not sing Fast Car. She had gone off stage when it was revealed that Stevie Wonder, the next singer up, was delayed. She would have to go back on – and when she did, she blazed through Fast Car. Wembley was speechless. Within a month, Fast Car had blazed up the charts in the UK and the United States. A (reluctant) star was born.

There was a backlash the following year with the arrival of her second LP, Crossroads. The public wanted more Fast Cars. Chapman was not the pandering kind, and the record embraced a variety of styles – there is more piano and a “brighter”, bigger sound.

It duly reached number one in the UK, but reviews were mixed. “As an album, Crossroads is not as focused or consistent as her debut,” said the Boston Globe – which must have hurt as she was still living in nearby Cambridge at that time. There was even a push against her fanbase – “Some critics suggested that her largely white audience embraced her socially conscious message as a way to assuage their middle-class liberal guilt,” said the New York Times in 1996.

Chapman continued to write and record, but it was increasingly clear she did not crave stardom. Her true passion was social justice. She has worked with Amnesty International, produced a video for Cleveland high schools celebrating African American achievement and last April received from South Africa its highest honour, the National Order – “recognising eminent foreign nationals for friendship shown to South Africa”.

Such are the accolades she truly cherishes, it is tempting to conclude. She almost certainly values them more than gold discs or applause. The Grammys have rekindled the world’s love for Tracy Chapman, but anyone expecting her to return the sentiment may be left waiting. All the indications are that, having briefly reminded us she still exists, the Fast Car singer is set to accelerate into the sunset once again.