The Western Balkans plan to rely on hydrocarbon as a quick and affordable replacement for coal. The region is now looking to secure new gas supplies from sources other than Russia with the support of the West. However, this diversification would come with new geopolitical and economic risks, while the new dependence on gas would further compromise the decarbonisation of a region heavily polluted by coal burning.

On the second Sunday in December, the Serbian city of Niš hosted a geopolitically noteworthy meeting of statesmen. Serbian President Vučić, known for his teetering between Russia and the West, together with the pro-Russian president of Bulgaria and the authoritarian ruler of Azerbaijan, launched a new gas pipeline linking Bulgaria and Serbia.

Along with the trio, the EU’s top official in Serbia also pressed the green button but was overshadowed by Vučić at the key moment for the cameras. Ironically, it was the EU who covered most of the costs of the project, with the intention to reduce the region’s dependence on Russian gas. This peculiar moment illustrates well how the interests of local politicians and global powers meet and clash in the geopolitical game for new gas supplies to the Western Balkans.

Western Balkan road from coal to gas

In 2022, when the energy crisis in Europe escalated shortly after the Russian aggression against Ukraine, it seemed that the golden era of energy from natural gas was over.

Governments of countries dependent on Russian gas, under pressure from growing prices and supply insecurity, urgently searched for ways out of the gas trap. However, within a few months, the volatile market calmed down, and the price stabilised thanks to the increased supplies of liquefied gas to Europe. European countries previously dependent on Russian gas were able to secure new sources in record time, and gas has largely rehabilitated its position as a reliable energy source.

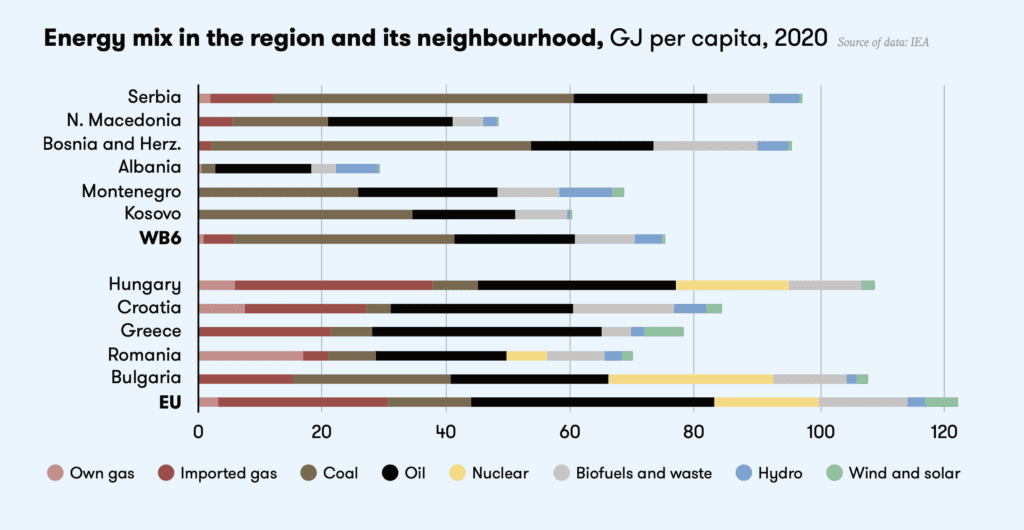

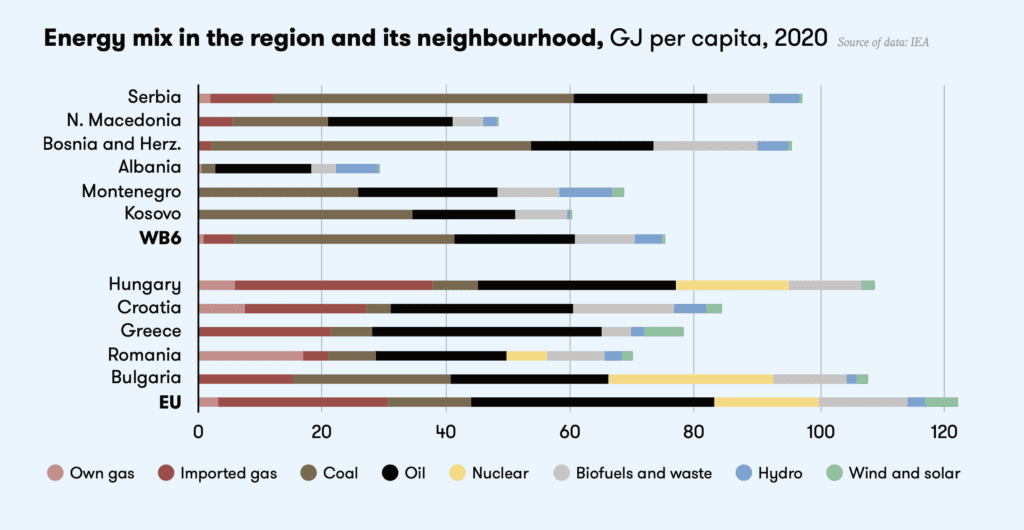

Despite recent experience with the risks associated with gas dependence, many European countries have decided to rely on gas as a transitional fuel in the gradual process of transition to green energy. Gas should play the role of a fast and available substitute for coal, which is expected to cease burning in most of the EU by 2030. The Western Balkans, a region that, unlike most of the EU states, has never been dependent on gas, is now looking to gas with the same intention.

While – at the EU level – gas accounts for a full quarter of total energy production, in the Western Balkans, its share is less than 8%.

Gas plays a more significant role only in the energy sector of Serbia and Northern Macedonia, where it is used as supplementary fuel for electricity and heat generation. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Albania have only marginal gas consumption, while Kosovo and Montenegro do not use gas in their energy sector at all.

The main reason for the significantly smaller use of gas compared to neighbouring EU regions is the weak infrastructure stemming from historically low gasification. Apart from Scandinavia, the Western Balkans are the only part of Europe without a developed gas distribution network.

Instead of gas, the Western Balkans have long depended on coal for energy production, which is still mined in large volumes in the region. Coal, burned mainly in outdated power stations built in the Yugoslav industrial era, is the main source of electricity and heat generation for all Western Balkan countries except Albania, leading to some of the most polluted air in Europe.

In addition to the environmental burden, dependence on coal comes along with increasing economic and political costs resulting from international pressure to decarbonise the energy sector. While in the EU, coal accounts for around one-tenth of the energy mix and is expected to be insignificant by 2030, it accounts for almost half of the total energy generation in the Western Balkans, and its replacement in the form of green energy is not yet in sight.

Gas might therefore seem to be a quick and affordable solution for the regional coal dependency.

However, geopolitics also comes into play in the discussion about the future replacement of coal and the role of gas. Gas supplies to the Western Balkans are subject to competition for influence in an unstable region, and the political interests of local and foreign actors often outweigh rational arguments in this debate.

The geopolitics of energy (in)dependence on Russia

Apart from small domestic reserves in Serbia and Albania, the gas sector in the Western Balkans has so far been entirely dependent on imports from Russia.

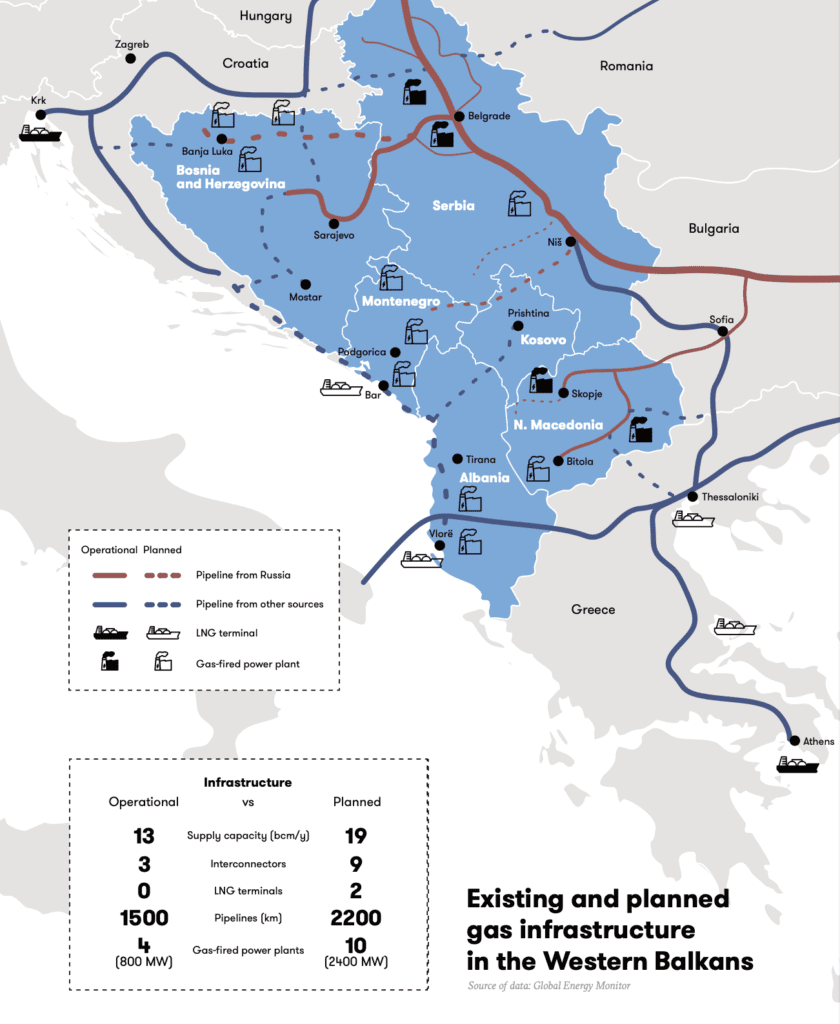

Gas has been delivered to the region since 2020 via a new branch of the TurkStream pipeline running through the Black Sea, Turkey and Bulgaria. Its Western Balkan part, which runs through Serbia to Hungary, was constructed as a joint project by Serbia and Russia to avoid transporting gas via Ukraine and became operational shortly before the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

So far, all existing gas infrastructure in Serbia, North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina has been connected solely to the Russian pipeline. Although gas supplies to these countries are negligible compared to the volumes Russia has until recently delivered to other parts of Europe, Moscow has exploited this dependence to strengthen its influence in the region.

The energy links to Russia are most pronounced in Serbia, which has long been oscillating between Russia, the West and China in its foreign policy.

Serbian President Vučić has deftly used the gas card in his domestic rhetoric, advocating the benefits of maintaining open relations with Moscow. In May 2022, shortly after the Russian aggression against Ukraine, Vučić boasted to his voters that he had renegotiated stable supplies and a lower price for Russian gas for Serbia directly with Putin.

Ironically, at the recent launch of a new gas pipeline from Bulgaria, he used quite a different rhetoric when he highlighted the benefits of diversifying gas sources for Serbia’s energy security.

Geopolitics is also central to the debate about gasification in internally divided Bosnia and Herzegovina (BaH). The political leadership of Republika Srpska, which has openly affiliated with Russia even during its aggression against Ukraine, is relying on Russia’s Gazprom in its ambitious gasification plans.

The Bosniak-Croat Federation of BaH is trying to break free from its dependence on Russian gas by connecting to infrastructure in neighbouring Croatia. However, the construction of a pipeline that would give the Federation access to the global LNG market via the Croatian Krk terminal is being blocked by a political dispute between Bosnians and Croats over who should have economic control over the strategic project.

Nihad Harbaš, a Bosnian energy and climate expert, points out that the issue of new gas supplies to the region is so pronounced mainly because of inevitable energy transition and strong political and economic pressures from the highest levels of domestic and international politics, including Russia and the US.

New sources in Azerbaijan and LNG market

Most governments in the region are aware of the political vulnerability arising from energy dependence on Russia, and the planned pipelines are therefore heading in other directions.

The main alternative would be to connect the region to the already operational TANAP and TAP pipelines, which have delivered gas from Azerbaijan to southern Europe via Turkey since 2020.

Although the TAP pipeline runs through the Western Balkans in Albania, no country in the region is yet connected to it. All Western Balkan states could, in the future, gain access to gas from Azerbaijan through planned interconnectors though.

Ironically, Serbia, the regional actor most loyal to Russia, was first among them. It decided to take advantage of European assistance in diversifying regional energy resources and, with significant financial support from the EU, built a new gas pipeline to Bulgaria, which connected its system to the new sources.

The interconnector gave Serbia access to Azerbaijani gas, the purchase of which Vučić had already negotiated during his frequent meetings with President Aliev. The interconnector will also provide Serbia with access to LNG terminals in Greece, through which it can buy liquefied gas on the global market in the future.

Liquefied natural gas should become another key source for the gasification of the entire Western Balkans. Already today, LNG is flowing to Southeast Europe via terminals in Greece and Croatia, whose capacities should increase significantly in upcoming years.

In addition, Albania and Montenegro are considering building their own smaller terminals to supply the new pipelines and power plants. The main political and economic force behind these ambitious projects to connect the region to the LNG market is the United States.

New geopolitical and economic risks

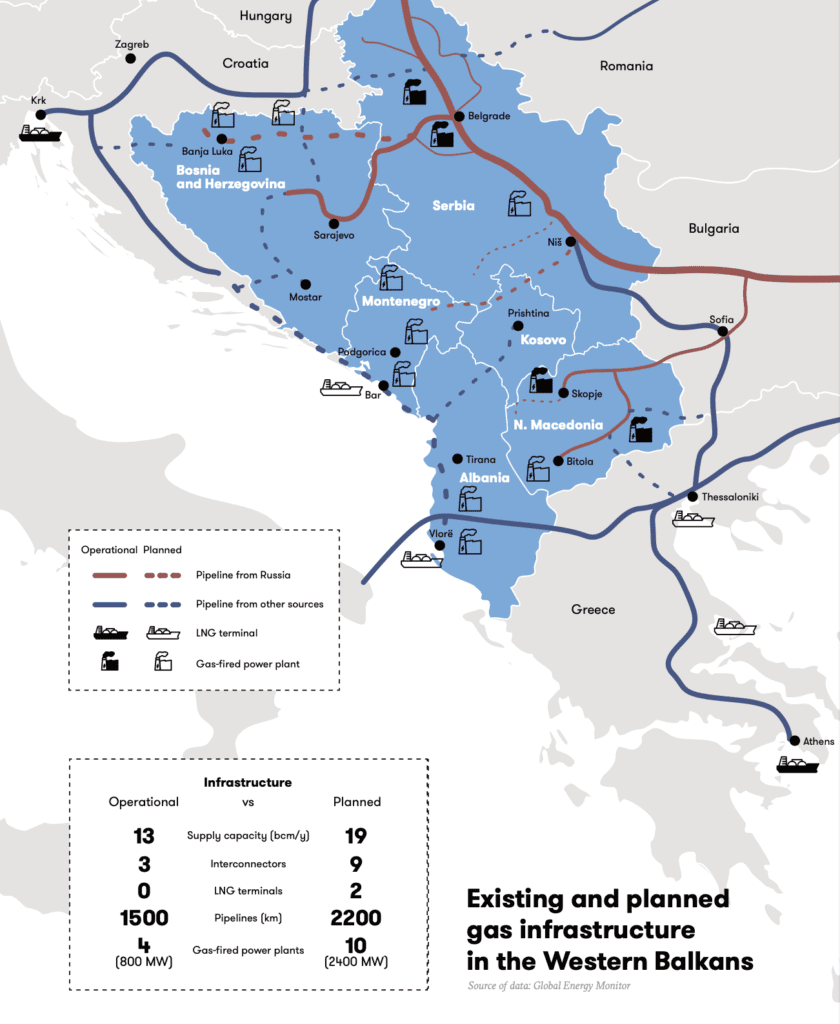

If all the ambitious plans to bring in gas from new sources are materialised, the region’s gas supply capacity would more than double thanks to thousands of kilometres of new pipelines and new LNG terminals.

Gas transported from Azerbaijan and by sea from other continents would supply up to ten new gas-fired power plants. However, even such diversification of gas sources would come with significant political and economic risks.

Azerbaijan, the main alternative supplier of non-liquefied gas, has profiled itself as a reliable energy partner for Europe, unlike Russia. Yet it is also an authoritarian state which, in its recent military takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh, has shown that it does not restrain from asserting its vital interests by force.

Recent years have also seen a rapprochement between President Aliev’s regime and Russia, from where Azerbaijan has begun to import gas to cover its domestic consumption and growing exports. Moreover, the only pipeline carrying gas from Azerbaijan’s Caspian fields to Europe passes through the volatile Caucasus and Turkey, which is a close ally of Azerbaijan and has its own hard-headed policy vis-à-vis Europe.

In contrast, the global LNG market, the second main planned source of gas for the Western Balkans, would provide a real diversification of sources.

LNG can be freely purchased from suppliers across different continents who compete for consumers. However, a free global market that is not bound by fixed pipelines also carries its risks, especially economic ones.

As the turbulent months of the energy crisis and Russian aggression against Ukraine have shown, the supply and price of LNG on the world market are difficult to predict. Also, the costs of building new terminals and associated gas infrastructure are enormous.

The long-term economic uncertainty of LNG supplies should lead Western Balkan governments to caution, according to Bankwatch’s analysis. From a geopolitical perspective, it is also important to consider that much of the liquefied gas entering the global market originates from Russia and other authoritarian states, as well as politically unstable regions in the Middle East, the Maghreb or the Gulf of Guinea. Moreover, the entire LNG market is vitally dependent on the security of shipping routes that pass through vulnerable bottlenecks.

Experts in the region also point to the risks associated with the strong US lobby behind plans to increase gas supplies through LNG imports.

They fear that it will bring profit primarily to the US gas exporters, while the weak Western Balkan economies and especially citizens as end-users of the energy will be exposed to uncertainty in the future due to volatile prices.

American interests and the European dilemma

Plans to bring gas from new sources to the Western Balkans would not have come about without strong political and economic support from the EU and the US, two key Western players in the region. They are both concerned by the Russian influence in this unstable region and see diversification of gas sources as one of the tools to weaken it. However, the interests of the EU and the US diverge to some extent in this field.

From the American perspective, boosting the role of gas in the region is clearly a profitable calculus from which the US can benefit politically and economically.

In addition to reducing Russian influence in the region, which is still at the centre of the US foreign policy, connecting the region to the LNG market would present an interesting business opportunity for the export-oriented US gas sector.

American LNG currently accounts for about half of the gas imports processed at terminals in Croatia and Greece. Unsurprisingly, the planned new terminals and pipelines connected to them in the region thus have strong support not only from the US gas industry but also from American diplomats in the region lobbying for them by local governments.

The EU’s position on the future role of gas in the Western Balkans is much more multifaceted. As the main guarantor of fragile stability in the region, Europe is also sensitive to Russian influence and has a strong geopolitical interest in its elimination. A significant part of the EU’s new financial aid package to the region is therefore directed toward the diversification of energy sources, including the construction of new gas interconnectors.

At the same time, the EU is pushing the Western Balkan countries to move faster towards green energy as part of their EU accession process. However, the intended decarbonisation of regional energy may be significantly delayed by increased reliance on gas.

A new analysis by international environmental organisation Bankwatch warns that EU-backed construction of new pipelines could lock the Western Balkan states into a new gas dependency for decades to come. European officials in the region, off the record, admit that the era of European support for new gasification projects is therefore coming to an end.

Gas trap for the green transition

The planned increase in gas supplies to the Western Balkans poses a major risk to the region’s path towards green energy.

The energy transition is inevitable in a region dependent on burning coal in obsolete power plants, not only because of political pressure from the EU and economic pressure from the energy market but, above all, because of the extreme levels of pollution. Regional capitals regularly top the list of cities with the worst air pollution, which is estimated to be responsible for tens of thousands of premature deaths a year.

Gas may appear to be an affordable replacement for coal, but it does not provide an environmentally sustainable solution. Although gas is tolerated in the EU for the time being as a ‘transitional technology’ on the path to green energy, it is still a fossil fuel with high emissions. While its combustion directly produces around two-thirds fewer emissions than coal, when methane emissions from extraction and transport are taken into account together with the energy intensity of the processing chain, the carbon footprint of the two fuels is almost equal.

The Western Balkans, with their ambitious gasification plans and costly investment into new gas supplies, risk merely replacing their current coal dependence with a new dependence on another fossil fuel that will soon suffer a similar fate. The region would thus willingly and with the direct assistance of the West lock itself into a trap of new geopolitical and economic risks.

The whole big strategic game over gas supplies to the Western Balkans could, in a broader context, look like an unnecessary big fuss that will soon fizzle out. However, the recent launch of the new gas interconnector from Bulgaria or the construction of the Balkan branch of the Russian pipeline in 2020 shows that, with sufficient political and economic backing from abroad, ambitious plans can be realised.

The smiling faces of controversial political leaders at the recent opening ceremony should be a warning signal to the region and the EU that the projects may ultimately benefit powerful political players and their own interests rather than local citizens.

This article was produced with the support of the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. More data about gas supplies in the region can be found in this factsheet on the AMO website.

Petr ČermákPetr Čermák is a Research Fellow at the Association for International Affairs (AMO), an independent think tank based in Prague. His primary research areas encompass politics and security in the Western Balkans. He earned his Ph.D. in international relations from Masaryk University in Brno and has undertaken research and academic pursuits at universities in Sarajevo, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Graz, and Tirana. His recent endeavors involve research projects centered around the energy transition and foreign influences in the Western Balkans, as well as the formulation of Czech foreign policy towards the region.