I'm a Doctor in Gaza. My Clinic Has No SinkPublished Feb 15, 2024 at 3:45 AM ESTUpdated Feb 15, 2024 at 7:34 AM EST

00:58

ICJ Orders Israel To Prevent Genocide In Gaza

By Musallam M. Abukhalil

21

I'm a physician employed by UNRWA, the UN agency responsible for Palestinian refugees. I'm stationed in the Nuseirat refugee camp in the central area of the Gaza Strip and I manage a primary care outpatient clinic in one of the UN shelters.

I live near the shelter where I work. My family was forced to leave our house three weeks ago to go to Rafah because the Israeli army marked major neighborhoods inside the Nuseirat camp as active military zones, so we were extremely fearful for our safety.

Just one month ago, I narrowly escaped death. There was an airstrike near the street where I travel every day to and from work. If I was late home by two minutes, I would have been blown to pieces.

There is a significant personal risk, but because of the new situation in Rafah—Israel is planning to storm in—my family has returned again from living in a tent there to our home in Nuseirat. We are always in constant fear for our safety.

In my clinic, we see close to 150 patients every day. We don't take any days off because the internally displaced people sheltered inside here have continuous medical needs; we work all seven days a week.

The kind of medical problems we see are mainly because of the uncleanliness of the bathrooms shared by hundreds of people. There are many sorts of infectious diseases inside the shelter, including gastrointestinal diarrhoea and respiratory disease, and even infestation of lice.

We have never seen this before. I have directly observed many cases of young women and children whose scalps are infested with lice.

But we don't have the medical supplies or treatment for them. We don't have anti-lice shampoo to treat them properly; nor do we have a sufficient water supply for them to take regular baths to maintain their personal hygiene.

Personal hygiene is very bad and control of infectious sources is getting worse, largely because so many people from inside and outside of the shelters are sharing bathrooms.

Adding to this complexity, we don't have medicines that can cover the full course of treatment for our patients. For example, instead of giving a patient one full strip, 10 tablets, of anti-fever medication, we give them just four tablets because we don't have enough. Undertreating these patients is a major problem.

Patients aren't getting the same quality and standard of care as before the war. We are working in an extremely challenging situation and I witness it every single day, as do the other shelters.

Because the primary care outpatient clinic is sponsored and run by UNRWA, we get our medical supplies and medicines exclusively from them. We don't have any other international partners or international response mechanisms that can give us medication.

If we run out of medicines from UNRWA, we don't have anything to give our patients. We are entirely dependent on UNRWA and its ability to continue its operations in our shelter.

There is a cluster of UN school shelters around us that also house primary care outpatient clinics like ours, but all of them are dependent on UNRWA, too. It's the only resource we depend on—and it's a critical one. I can't imagine any way our work could continue without it.

We rely on foreign aid. If that's cut off, we don't have anything to feed or treat ourselves with.

It may be shocking to read, but the extreme limitation of medical resources means we don't have an excellent standard of infection control in our clinic, which is a converted classroom. I depend on my personal items; I have my own alcohol scrub and face mask. It's not very well organized, but that's the only way we can handle the situation.

We also don't have our own sink inside the room because it was not designed to have one, so the clinic doesn't have washing water. I do my best to use my alcohol rub before and after treating and seeing patients, but this is dependent on my own resources.

Other than that, I counsel patients on basic hygiene guidance. Sometimes I get laughed at because I'm counseling them on things they cannot provide for themselves. I tell them they have to wash themselves, they need a clean water supply, and so on—everything related to preventative medicine. I always get a sarcastic reply.

But this advice is the only thing I can help people with. Considering what I see, though, the majority of them are not able to follow the advice I give because they don't have access to what they need.

Seeing all this gives me an awful feeling of powerlessness; that I cannot utilize my medical knowledge to provide my patients with the best results that I normally can.

The only solace I can give myself is that many of my patients see improvements in their health because I have a good internal management protocol for these conditions, especially respiratory infections. These can be excellently managed inside my clinic because I have a relatively sufficient supply of resources and many people can follow my advice.

But lice infestation has been my clinic's number one medical problem. Every day, people come to my clinic asking if there is a refill of anti-lice shampoo that I can provide.

It makes me feel bad because I cannot see similar improvements with these patients and others with personal hygiene issues as I have done with respiratory infections.

I consider myself to be a resilient person. I have lived and worked inside Gaza for the entirety of my life. I am 30 years old. I only traveled outside Gaza for a limited amount of time. And because I have been in similar situations, they give me resilience. I always have hope.

I am only concerned with trying to influence the present moment. I do my best to give the highest medical care that I can, and I don't concern myself with the larger picture that only other actors are powerful enough to influence. Politics is extremely outside of our influence.

It gives me optimism to be able to persuade myself that I am a good person who wants to do good in the community that surrounds me, and that's enough for me to stay positive.

I think the Palestinian people, of all people of the world, are resilient and can cope very well. That's my biased opinion.

The most important message I can relay to people outside Gaza is they have to do everything they can to make a ceasefire a reality, now. People are being killed in massive numbers and there is a tremendous amount of misery here.

I fear for the next generation in this continuing conflict because the current situation will be a breeding ground for extremism and radical ideas that will not contribute to the peace-building process.

The more that the ceasefire is delayed, the more the formal peace process will be delayed, like it has for many generations.

People must relate to our experience on a personal level by remembering that we all are humans who want to be free and safe; to have enough food and electricity. We are asking for basic human rights. I don't think we are asking for luxurious things or special privileges.

If someone with a clean conscience and a heart full of humanity understands what our message is as Palestinians who live and work in Gaza, then they will be active participants in the political demonstrations asking for a ceasefire.

My last message is this: We need more medical assistance. We need more people to visit us. I want people to come visit my clinic inside this shelter and Nuseirat camp.

I want them to see our work, to see our patients, to see our extensive documentation of these terrible diseases, and to propose ideas for providing more medicine and capacity-building to cope with the growing medical needs of our local communities, who are internally displaced. The majority of people whom I treat are actually from the northern part of Gaza.

Medical assistance and a ceasefire are urgent and must be acted upon now.

Musallam M. Abukhalil is a Palestinian physician in Gaza's Nuseirat refugee camp.

All views expressed are the author's own.

As told to Shane Croucher.

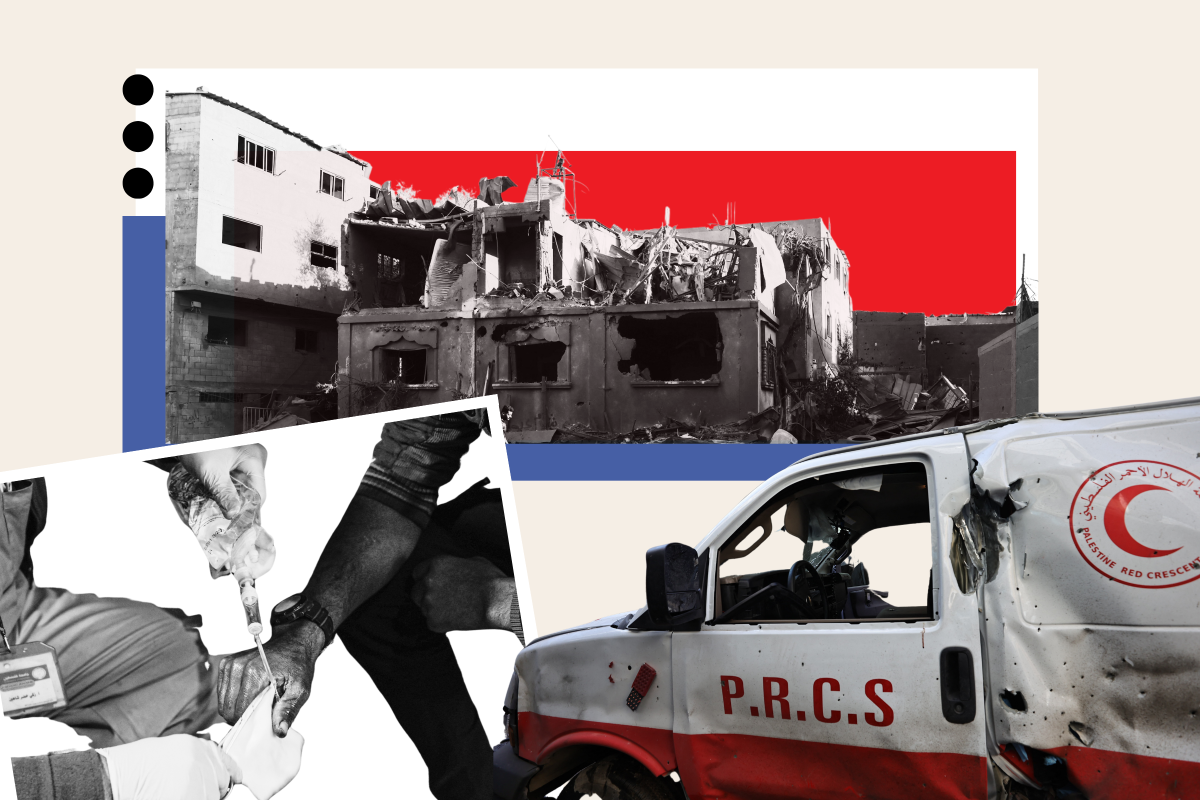

Israeli attacks on Gaza continue ( Ahmed Zaqout - Anadolu Agency )

Israeli attacks on Gaza continue ( Ahmed Zaqout - Anadolu Agency )