[By Lucía Cuberos]

Every day, sailors on fishing vessels around the globe turn off their tracking systems and vanish from the gaze of authorities.

There are legitimate reasons for ships to disappear in this way from the Automatic Identification System (AIS) that broadcasts their identities and locations – including seeking to avoid pirates. But the practice has been linked to oil smuggling, gun running and human trafficking.

In the Atlantic waters off South America, Lieutenant Commander Hugo de Barros of the Uruguayan Navy watches for tell-tale signs of a different activity linked to this “going dark”: illegal fishing.

De Barros is interim head of the fleet command’s search-and-rescue center, which is responsible for monitoring Uruguay’s water. He says the navy has tools that enable it to approximate ships’ locations while dark. “When we see these vessels disappear and show up in the system, it creates clues and patterns that allow us to determine if they are in a suspicious situation of illegal fishing.”

Such illegal fishing threatens tuna, sharks, swordfish, turtles and seabirds in Uruguayan waters. It is a growing concern as the country seeks to safeguard its marine environment and establish more protected areas. The problem is compounded by a lack of resources for patrolling national waters, but this may be changing.

Out of the system and causing problems

Dark activity and the often-related issue of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is a growing global problem. According to one study, fishing vessels switch off their AIS systems around 6% of the time, in ways that suggests this is often related to IUU activity.

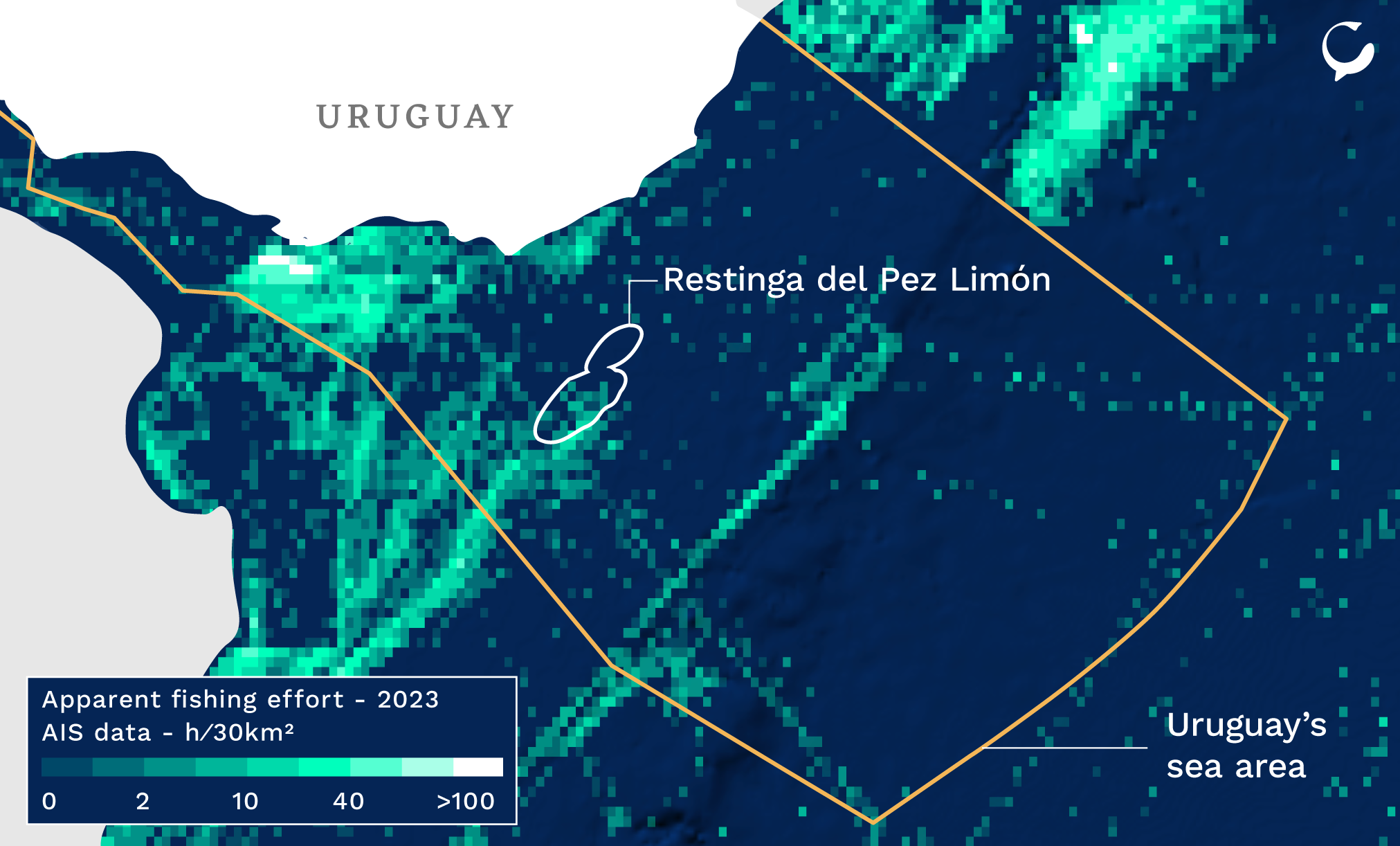

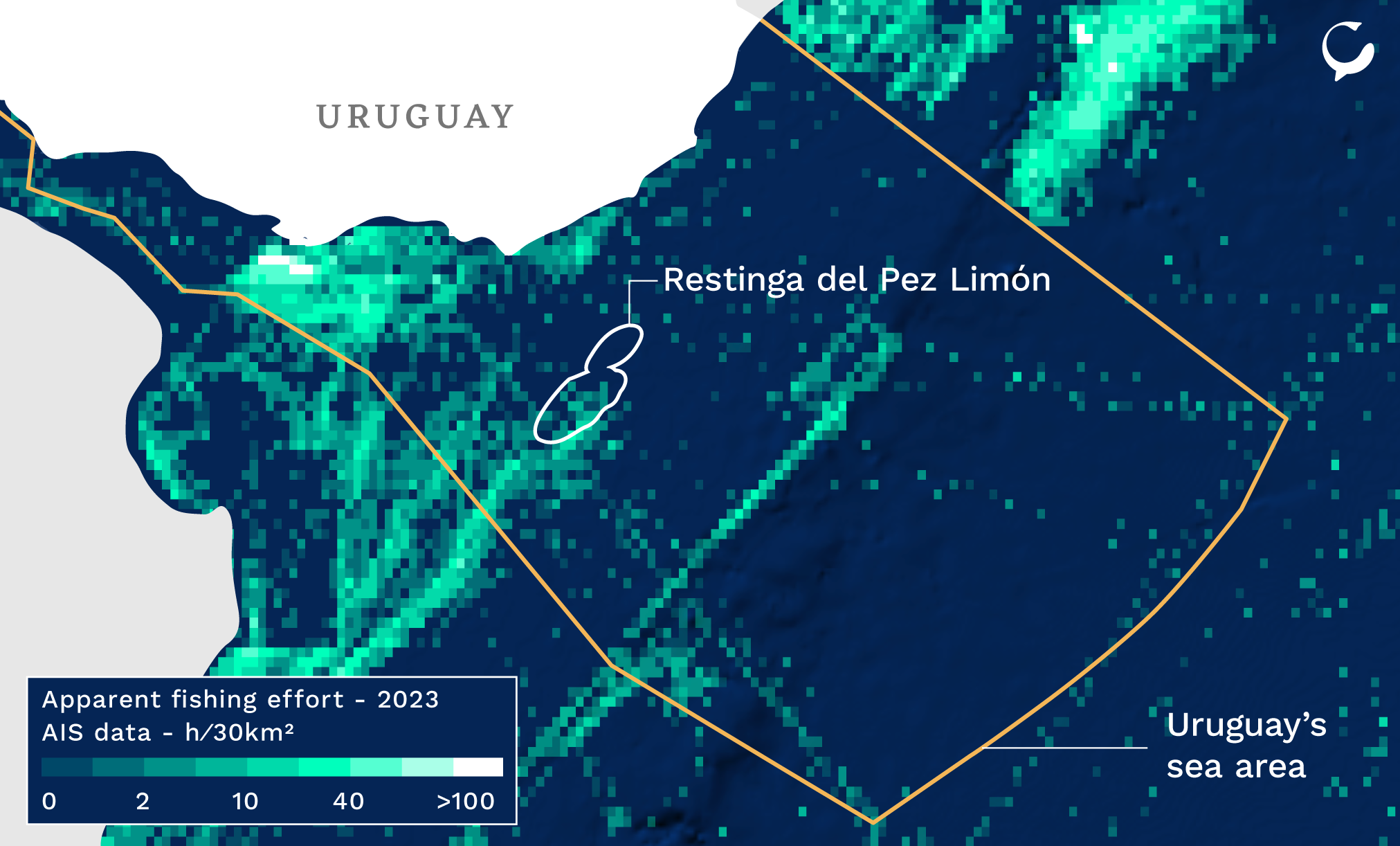

In Uruguay, where China Dialogue has previously reported problems with foreign fishing ships docking at the main port of Montevideo, there is concern that going dark may be on the increase. A study team from Mar Azul Uruguayo, a project of the NGO Che Wirapitá, analyzed 46 ships apparently fishing between November 2022 and November 2023 in an area identified by the environment ministry as a priority for conservation – the Restinga del Pez Limón. Using data from the tracking projects Global Fishing Watch and Skylight, they found 42 of these vessels switched off their AIS systems 736 times in that period.

(Data source: Global Fishing Watch; Map: China Dialogue Ocean)

According to their report, four of these were registered in Taiwan, and their dark activity took place in international waters, not within the area. Inside the Restinga del Pez Limón, 26 Argentinean-flagged vessels were responsible for 89% of the dark activity and 12 Uruguayan-flagged vessels for the remaining 11%.

Comparing just November 2022 and November 2023, the Mar Azul Uruguayo researchers found dark activity more than doubled in the Argentinean fleet, from 66 events to 162. Among the Uruguayan boats, it tripled from 13 to 40.

Andrés Milessi, the director of the group, says the efforts of many people to promote greater control of fishing are held back by the “obstacles and bureaucracy” of the state.

“There are many freely available surveillance tools at Uruguay’s disposal, but it depends on the political will to access them,” says Milessi.

He says a number of organizations are now trying to convince deputies and senators in the Uruguayan Congress to toughen up laws on illegal fishing. For the moment, however, “the boats are still coming in and out, and the authorities are pretending that it’s business as usual”.

Ship shortage hampers fisheries enforcement

According to De Barros, the navy’s lack of capacity has undermined its ability to combat illegal fishing. He says fishing and related activities, such as the transfer of catches between vessels, constitute “about 99% of the dark activity that is recorded”.

At the end of 2022, the navy obtained vessels to patrol the Uruguay River. But De Barros says “we are most depleted” in the Río de la Plata, where the Uruguay River flows into the ocean, and in the Atlantic itself. He says the navy currently has only three vessels capable of navigating these waters, two of which “are quite limited in terms of speed”.

In December, the Ministry of Defence signed off the purchase of two ocean-going patrol vessels as it moves to strengthen the navy’s capacity to protect territorial waters. These are in addition to other boats already acquired during the current government, which took power in 2020, including four launches, a search-and-rescue ship, and a scientific vessel.

According to De Barros, the new patrol boats “are fundamental because they are specifically designed to meet [our] needs”. Most importantly, they will increase the navy’s deep-water surveillance capability, both directly and through their ability to carry helicopters that can travel even further and faster. “We gain a much greater response capability,” he says.

De Barros says he is unaware of the figures reported by Mar Azul Uruguayo but believes that any increase in the problem is probably due to the lack of navy vessels.

Although the construction of the new vessels “will take time”, he hopes they will be a lasting solution. “Not like what has happened in recent years, when friendly countries give us material that is already at the limit of its useful life, generating very limited capacities.”

Fishers flit through legal loopholes

Another issue has been undermining the fight against illicit fishing. “Nowadays, illegal fishing in Uruguay is considered an administrative infraction and not a crime under the penal code,” explains De Barros. This limits the actions the navy can take. A vessel caught fishing illegally is usually fined and eventually has its cargo confiscated, but no one can be arrested or prosecuted.

Other navy sources, who spoke to China Dialogue Ocean on condition of anonymity, say the current law “has their hands pretty much tied”. Some countries allow their militaries to take strong action against foreign vessels that contravene their rules. Argentina has been known to open fire at and even sink vessels it accuses of fishing illegally.

Juan Riva Zucchelli, the president of Uruguay’s Chamber of Fishing Industries, tells China Dialogue Ocean that when vessels break the rules and are detected, they may be detained, but in the end “they return to their own waters”.

He also worries that the navy’s capacity “is very low… We all know the resource and fuel problems the navy has,” he says. “We don’t have what we should have to protect the country’s wealth.”

Despite this, Riva Zucchelli insists that “there are not so many cases” of illegal fishing in Uruguayan waters.

“NGOs, in the name of protection, go overboard with the numbers. I’m not against what they do, but sometimes they raise alarms because they want to protect more than they should,” he says.

Getting tough

China Dialogue Ocean tried unsuccessfully to contact Uruguay’s National Directorate of Aquatic Resources for comment on this story.

But Environment Minister Robert Bouvier has said illegal fishing is “being worked on in close inter-institutional collaboration”, especially in view of the new marine protected areas that the ministry is considering establishing.

In addition to preparing for its new vessels, sources say the navy has recently begun training an illegal fishing analyst, and a first report on the issue should be published in May. It is also developing and deploying technology that correlates satellite imagery, AIS data and other information to track vessels, and using artificial intelligence to analyse whether they are engaged in suspicious fishing activities.

“This technology makes it possible to see through clouds or at night using synthetic aperture radar, and to detect ships that do not want to be detected and photograph them,” De Barros explains.

With the navy’s rising capacity, going dark off the coast of Uruguay may not be enough for boats to get away with illegal fishing in the future.

Lucía Cuberos is a journalist based in Uruguay. She writes for Búsqueda magazine.

This article appears courtesy of China Dialogue Ocean and may be found in its original form here.

Top image: Uruguay's main naval base in Montevideo (Vaimaca / CC BY SA 3.0)

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.