Let’s reject all settlers myths this Thanksgiving and honor Indigenous resistance.

By Johnnie Jae ,

November 28, 2024

The Barracks on Alcatraz Island greets you with a welcome that has remained since the occupation in 1969.Johnnie Jae

Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

For many Americans, Thanksgiving is a time to gather with loved ones, share a meal, watch football and express gratitude. Some Native Americans celebrate Thanksgiving this way as well, because feasting is Indigenous — we also love eating and watching football.

Still, the holiday carries a much heavier weight: It is a stark reminder of the violent colonization that began with the arrival of European settlers. The idyllic myths surrounding Thanksgiving align with broader strategies of historical revisionism used to justify settler colonialism by distorting and erasing histories of violence, exploitation and resistance. They reinforce settler identity and national pride and discourage critical engagement in our complex histories. These strategies serve to normalize colonization, valorize settlers and silence Indigenous voices.

Yet, even in the shadow of these painful histories, Native communities have found ways to challenge the sanitized myths of Thanksgiving and call for a reckoning with the true history of the United States, encouraging reflection, accountability and action to support Indigenous rights and justice. At the same time, the holiday serves as an opportunity to reclaim whitewashed narratives and assert Indigenous presence, reminding the world of the unbroken spirit of Native nations.

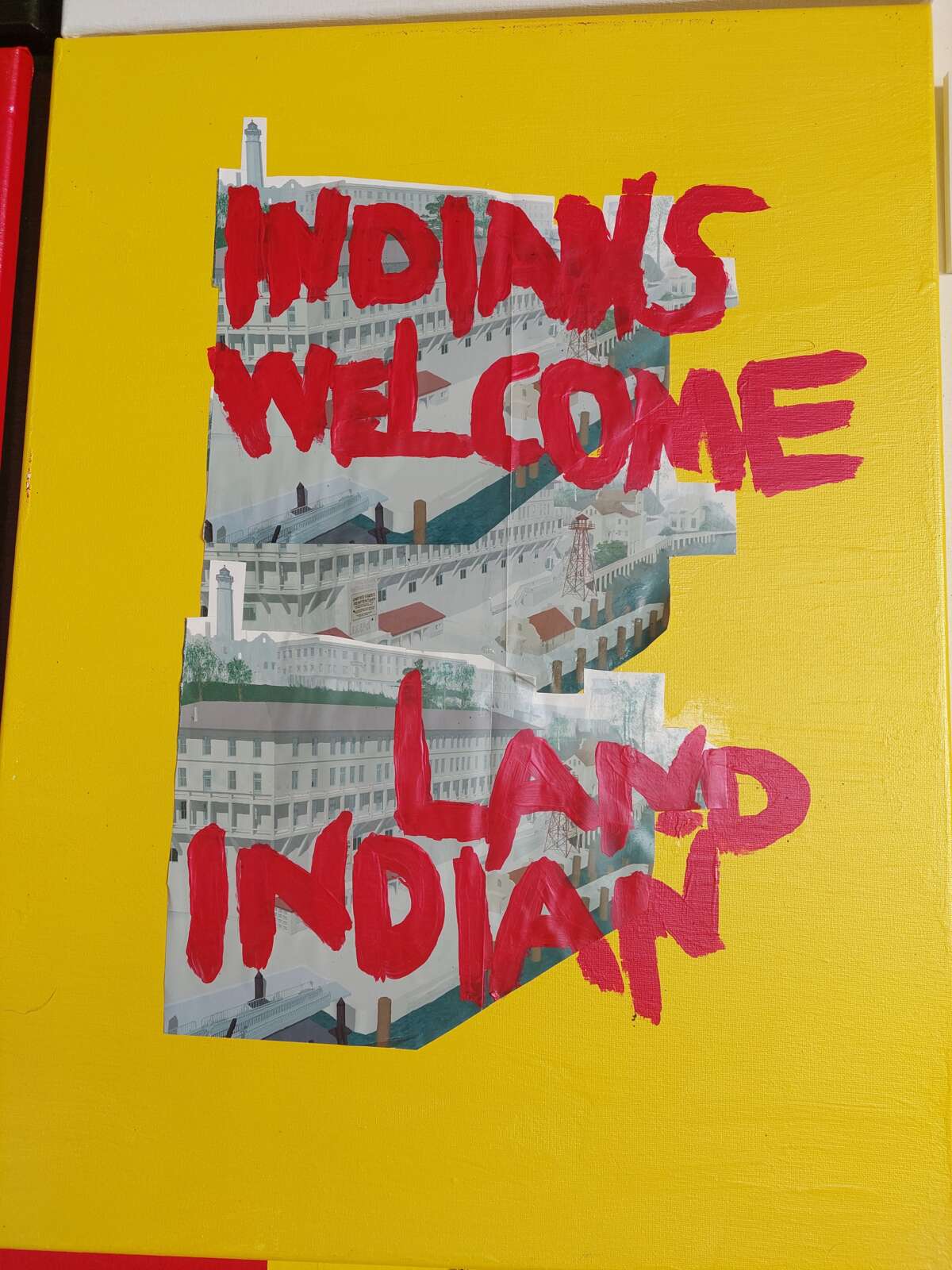

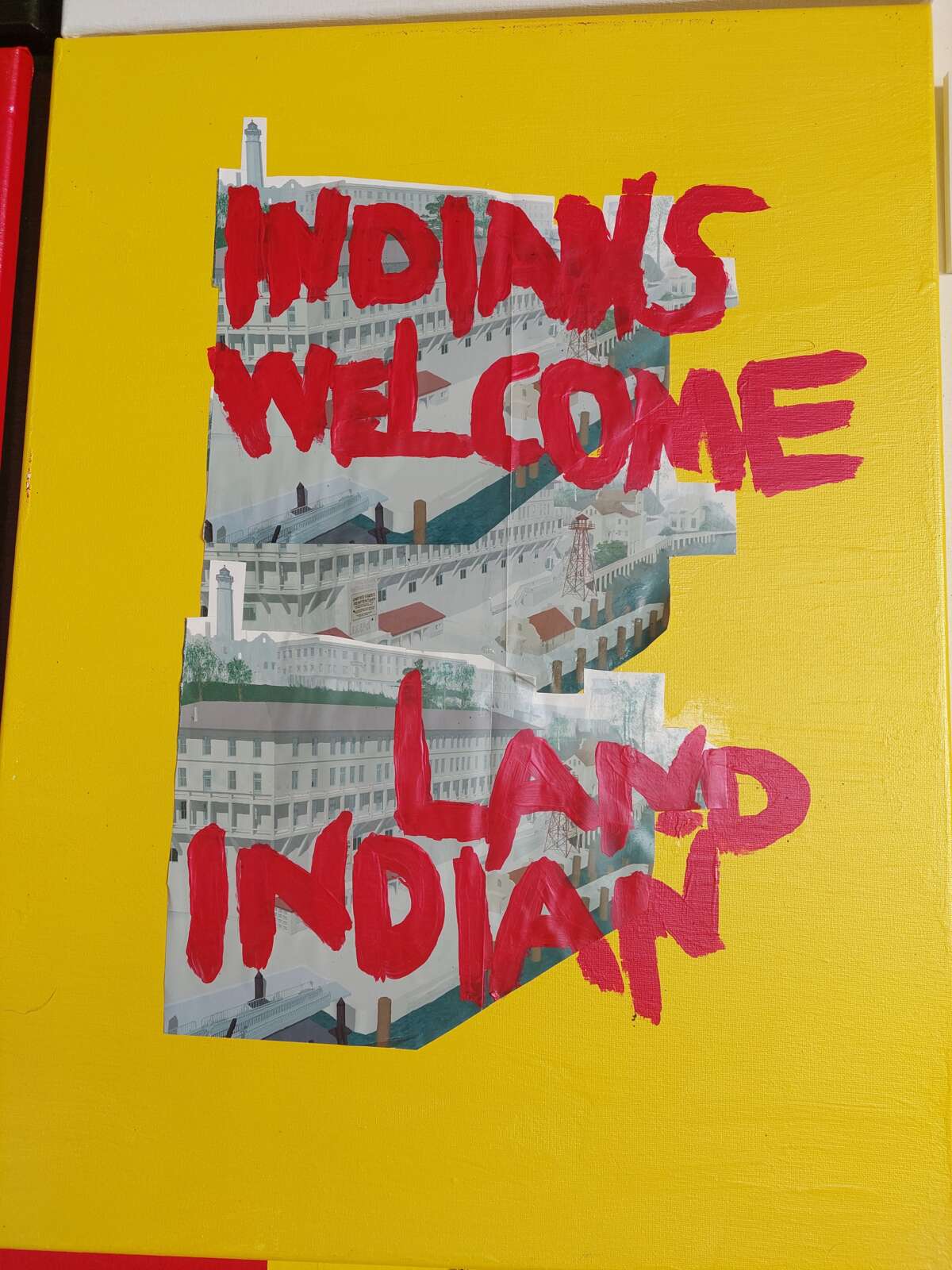

A collage featured in the Red Power on Alcatraz Perspectives 50 years Later exhibit.Johnnie Jae.

A collage featured in the Red Power on Alcatraz Perspectives 50 years Later exhibit.Johnnie Jae.

In November 1969, a group of young Native activists, who became known as “Indians of All Tribes,” sought to draw attention to the federal government’s failure to honor treaties, the dire conditions on reservations, and the systemic erasure of Indigenous cultures by occupying Alcatraz Island after a fire destroyed the American Indian Center in San Francisco. From November 20, 1969, to June 11, 1971, activists took control of the island, citing the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), which they argued gave them the right to claim unused federal land.

During their 19-month occupation, they transformed Alcatraz into a symbolic space of resistance, using it as a platform to advocate for sovereignty, education and cultural renewal. Though the protest ended when federal authorities forcibly removed the occupiers, it was a pivotal moment that reinvigorated the Indigenous rights movement.

Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

For many Americans, Thanksgiving is a time to gather with loved ones, share a meal, watch football and express gratitude. Some Native Americans celebrate Thanksgiving this way as well, because feasting is Indigenous — we also love eating and watching football.

Still, the holiday carries a much heavier weight: It is a stark reminder of the violent colonization that began with the arrival of European settlers. The idyllic myths surrounding Thanksgiving align with broader strategies of historical revisionism used to justify settler colonialism by distorting and erasing histories of violence, exploitation and resistance. They reinforce settler identity and national pride and discourage critical engagement in our complex histories. These strategies serve to normalize colonization, valorize settlers and silence Indigenous voices.

Yet, even in the shadow of these painful histories, Native communities have found ways to challenge the sanitized myths of Thanksgiving and call for a reckoning with the true history of the United States, encouraging reflection, accountability and action to support Indigenous rights and justice. At the same time, the holiday serves as an opportunity to reclaim whitewashed narratives and assert Indigenous presence, reminding the world of the unbroken spirit of Native nations.

A collage featured in the Red Power on Alcatraz Perspectives 50 years Later exhibit.Johnnie Jae.

A collage featured in the Red Power on Alcatraz Perspectives 50 years Later exhibit.Johnnie Jae.In November 1969, a group of young Native activists, who became known as “Indians of All Tribes,” sought to draw attention to the federal government’s failure to honor treaties, the dire conditions on reservations, and the systemic erasure of Indigenous cultures by occupying Alcatraz Island after a fire destroyed the American Indian Center in San Francisco. From November 20, 1969, to June 11, 1971, activists took control of the island, citing the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), which they argued gave them the right to claim unused federal land.

During their 19-month occupation, they transformed Alcatraz into a symbolic space of resistance, using it as a platform to advocate for sovereignty, education and cultural renewal. Though the protest ended when federal authorities forcibly removed the occupiers, it was a pivotal moment that reinvigorated the Indigenous rights movement.

Op-Ed |

Racial Justice

Thanksgiving Can Never Be Redeemed From Its Colonial Past. Let’s Abolish It.

The work of decolonization means refusing the banal evil of Thanksgiving.

By Amrah Salomón , Truthout November 24, 2022

In the spirit of the Alcatraz occupation, Unthanksgiving Day, also known as the Indigenous Peoples Sunrise Ceremony, has been organized by the International Indian Treaty Council and held annually on Alcatraz Island since 1975. The Unthanksgiving sunrise ceremony honors the legacy of the Natives who occupied Alcatraz and fosters solidarity among Natives and non-Natives. It serves as a celebration of Indigenous survival and the ongoing fight for justice.

Native communities have found ways to challenge the sanitized myths of Thanksgiving and call for a reckoning with the true history of the United States.

In 1970, while the occupation of Alcatraz was ongoing in San Francisco, across the country on the East Coast, the United American Indians of New England established the Day of Mourning. The Day of Mourning held every year in Plymouth, Massachusetts, includes a march through Plymouth’s historic district to Cole’s Hill, where invited speakers speak about Native histories and the struggles taking place in our communities and beyond. The event was conceived after Wamsutta, an Aquinnah Wampanoag leader, was invited to speak at the commemoration of the 350th anniversary of the arrival of the pilgrims in Plymouth, Massachusetts. After his planned speech — which criticized the glorification of the whitewashed Thanksgiving narrative and detailed the atrocities committed against Indigenous peoples — was censored, he and other Indigenous activists gathered to mark the first Day of Mourning.

One of the most poignant moments in the speech that Wamsutta had planned was a reminder of our humanity:

History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt, and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood.

While the Day of Mourning acknowledges the historical injustices and mourns the loss of our ancestors, it is also a celebration of Indigenous survival, resilience and identity. Participants honor their ancestors through prayer and fasting while raising awareness about land sovereignty, environmental justice and the rights of Native people.

Indigenous peoples in the United States and Palestinians in Gaza have faced similar patterns of land dispossession and territorial fragmentation under settler-colonial systems.

The Day of Mourning also connects struggles faced by Indigenous peoples worldwide, highlighting the shared impacts of colonization and the need for collective resistance, which weighs heavily on Native communities as we bear witness to Israel’s war on Gaza.

Across continents and centuries, Indigenous peoples in the United States and Palestinians in Gaza have faced similar patterns of land dispossession and territorial fragmentation under settler-colonial systems. In the U.S., policies like the Indian Removal Act forcibly displaced Indigenous nations from their ancestral lands and pushed them onto reservations often located on economically and ecologically marginal terrain. The Dawes Act compounded this dispossession by fragmenting tribal territories and reducing Indigenous landholdings by millions of acres.

Likewise, Palestinians faced mass displacement during the Nakba in 1948, with thousands forced into refugee camps. This dispossession continues today through land confiscations and expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank. Meanwhile, Gaza remains isolated under a blockade that restricts movement and access, further severing Palestinians from their homelands

.

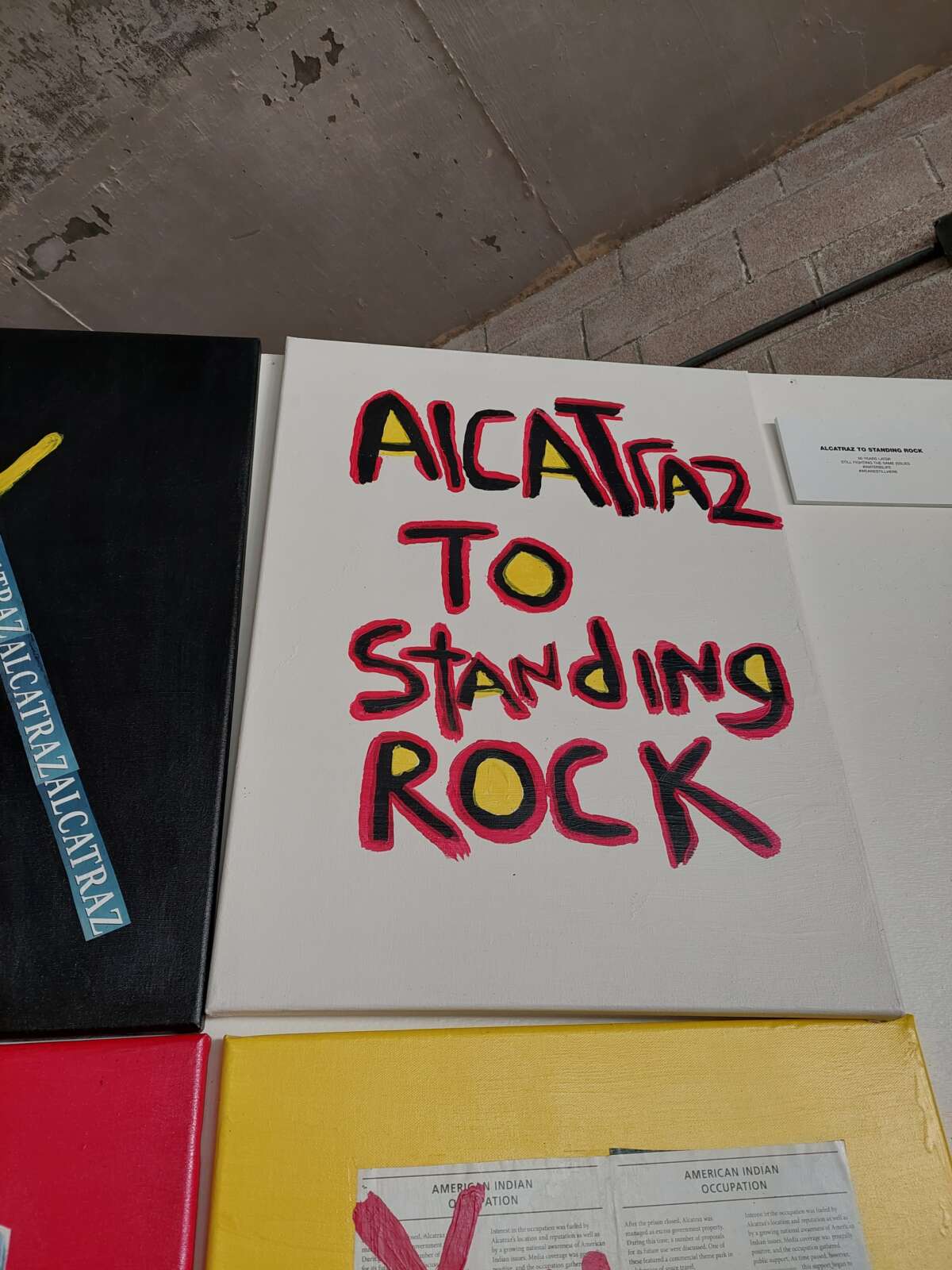

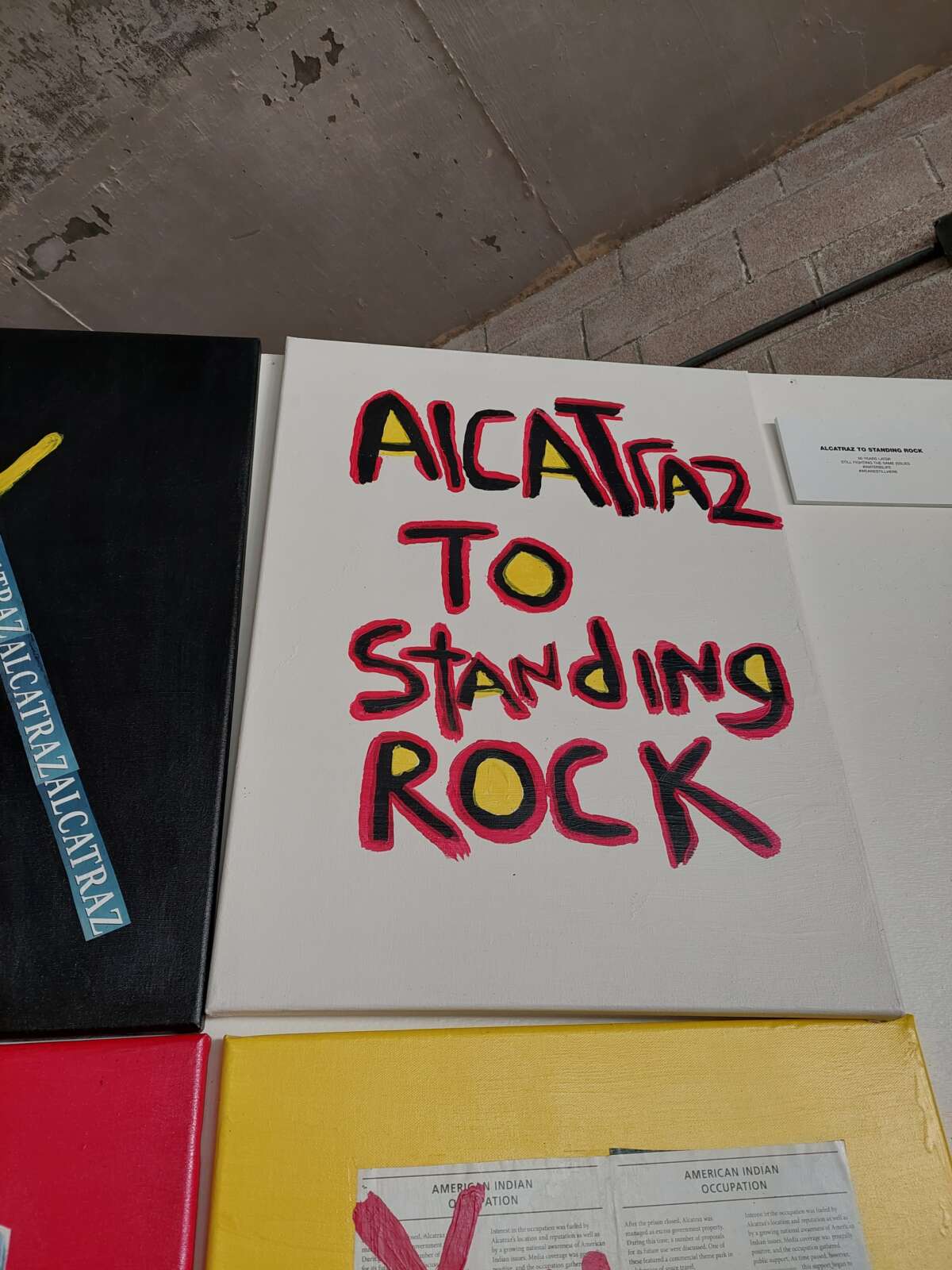

A sign reading From Alcatraz to Standing Rock is featured in the Red Power on Alcatraz Perspectives 50 years Later. Johnnie Jae

The erosion of sovereignty has been a central tool of oppression for both Indigenous peoples in the United States and Palestinians in Gaza. In the U.S., federal policies undermined the rights of tribal nations to self-determination by replacing traditional governance systems with federal oversight and forcing assimilation through initiatives like the Indian boarding school system, which sought to eradicate Native identities and sever the connection of Native youth to their communities.

These efforts to subjugate Native communities are not confined to the past.

On October 27, 2016, about 200 police in riot gear, along with soldiers from the National Guard, carried out a midday raid on a protest encampment at Standing Rock, where Water Protectors had gathered to block construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Over 140 people were arrested on charges, including criminal trespassing, rioting and endangerment by fire, the last stemming from vehicles allegedly set ablaze during the confrontation. The militarized response exemplified the lengths to which authorities go to protect corporate interests over Native lives and environmental justice.

The myths of Thanksgiving perpetuate a sanitized narrative of harmony and gratitude that erases the violent historical and contemporary realities of settler colonialism.

Meanwhile, Palestinians in Gaza face severe restrictions on self-governance, with Israel exerting control over borders, airspace and access to essential resources. The Oslo Accords further fragmented Palestinian governance, fostering dependence on international aid while denying meaningful autonomy. Palestinians also encounter systemic efforts to crush resistance through militarized surveillance, airstrikes and blockades to maintain Israel’s hold on the region.

For Native peoples, the destruction and suffering in Gaza are hauntingly familiar because they mirror the aftermath of tragedies like the Massacre of Wounded Knee and violent police attacks on Water Protectors at Standing Rock. These shared experiences highlight the devastating consequences of colonizers wielding violence to suppress resistance. However, while these tragic circumstances remind us of our shared history of violence, they also remind us that our people have a shared spirit of resilience and survival.

It’s important to understand these histories and the parallels that exist because crimes against humanity have a strange way of becoming pillars of American exceptionalism, “necessary evils” for the sake of “progress” and “manifest destiny” that, over time, become mythologized and celebrated as holidays — see Columbus Day, Independence Day and Presidents’ Day. Thanksgiving is no exception. I dread the possibility that someday a similar holiday could be invented to reframe Israel’s war on Gaza as a benevolent and just occurrence that should be celebrated.

The myths of Thanksgiving perpetuate a sanitized narrative of harmony and gratitude that erases the violent historical and contemporary realities of settler colonialism. By glorifying the arrival of European settlers and ignoring the intentional eradication and oppression of Indigenous peoples, Thanksgiving becomes less about gratitude and more of a tool for perpetuating historical erasure and distraction, further marginalizing Indigenous voices and struggles.

As Thanksgiving myths continue to shape public consciousness, there is a pressing need to disrupt those narratives and center the voices of those who have been silenced. By addressing the uncensored history of colonization and its ongoing impacts, we can encourage action toward Indigenous sovereignty, environmental justice and human rights on a global scale.

Thanksgiving, filtered through a Native lens of truth and resistance, can become a moment of reckoning — a time to give thanks for our survival, resistance and commitment to dismantling the structures of oppression that have persisted for centuries.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Johnnie Jae is an Otoe-Missouria and Choctaw journalist, speaker, podcaster, technologist, advocate, community builder and entrepreneur who loves empowering others to follow their passions and create for healing and positive change in the world. She is the founder of “A Tribe Called Geek,” an award-winning media platform for Indigenous Geek Culture and STEM as well as #Indigenerds4Hope, a suicide prevention initiative designed to educate, encourage and empower Native Youth who are or know someone struggling with bullying, mental illness and suicide. She is also the host of the “Indigenous Flame” and “A Tribe Called Geek” podcasts that originated on the Success Native Style Radio Network.

The erosion of sovereignty has been a central tool of oppression for both Indigenous peoples in the United States and Palestinians in Gaza. In the U.S., federal policies undermined the rights of tribal nations to self-determination by replacing traditional governance systems with federal oversight and forcing assimilation through initiatives like the Indian boarding school system, which sought to eradicate Native identities and sever the connection of Native youth to their communities.

These efforts to subjugate Native communities are not confined to the past.

On October 27, 2016, about 200 police in riot gear, along with soldiers from the National Guard, carried out a midday raid on a protest encampment at Standing Rock, where Water Protectors had gathered to block construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Over 140 people were arrested on charges, including criminal trespassing, rioting and endangerment by fire, the last stemming from vehicles allegedly set ablaze during the confrontation. The militarized response exemplified the lengths to which authorities go to protect corporate interests over Native lives and environmental justice.

The myths of Thanksgiving perpetuate a sanitized narrative of harmony and gratitude that erases the violent historical and contemporary realities of settler colonialism.

Meanwhile, Palestinians in Gaza face severe restrictions on self-governance, with Israel exerting control over borders, airspace and access to essential resources. The Oslo Accords further fragmented Palestinian governance, fostering dependence on international aid while denying meaningful autonomy. Palestinians also encounter systemic efforts to crush resistance through militarized surveillance, airstrikes and blockades to maintain Israel’s hold on the region.

For Native peoples, the destruction and suffering in Gaza are hauntingly familiar because they mirror the aftermath of tragedies like the Massacre of Wounded Knee and violent police attacks on Water Protectors at Standing Rock. These shared experiences highlight the devastating consequences of colonizers wielding violence to suppress resistance. However, while these tragic circumstances remind us of our shared history of violence, they also remind us that our people have a shared spirit of resilience and survival.

It’s important to understand these histories and the parallels that exist because crimes against humanity have a strange way of becoming pillars of American exceptionalism, “necessary evils” for the sake of “progress” and “manifest destiny” that, over time, become mythologized and celebrated as holidays — see Columbus Day, Independence Day and Presidents’ Day. Thanksgiving is no exception. I dread the possibility that someday a similar holiday could be invented to reframe Israel’s war on Gaza as a benevolent and just occurrence that should be celebrated.

The myths of Thanksgiving perpetuate a sanitized narrative of harmony and gratitude that erases the violent historical and contemporary realities of settler colonialism. By glorifying the arrival of European settlers and ignoring the intentional eradication and oppression of Indigenous peoples, Thanksgiving becomes less about gratitude and more of a tool for perpetuating historical erasure and distraction, further marginalizing Indigenous voices and struggles.

As Thanksgiving myths continue to shape public consciousness, there is a pressing need to disrupt those narratives and center the voices of those who have been silenced. By addressing the uncensored history of colonization and its ongoing impacts, we can encourage action toward Indigenous sovereignty, environmental justice and human rights on a global scale.

Thanksgiving, filtered through a Native lens of truth and resistance, can become a moment of reckoning — a time to give thanks for our survival, resistance and commitment to dismantling the structures of oppression that have persisted for centuries.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Johnnie Jae is an Otoe-Missouria and Choctaw journalist, speaker, podcaster, technologist, advocate, community builder and entrepreneur who loves empowering others to follow their passions and create for healing and positive change in the world. She is the founder of “A Tribe Called Geek,” an award-winning media platform for Indigenous Geek Culture and STEM as well as #Indigenerds4Hope, a suicide prevention initiative designed to educate, encourage and empower Native Youth who are or know someone struggling with bullying, mental illness and suicide. She is also the host of the “Indigenous Flame” and “A Tribe Called Geek” podcasts that originated on the Success Native Style Radio Network.

Nick Estes on Thanksgiving, Settler Colonialism & Continuing Indigenous Resistance

November 28, 2024

Source: Democracy Now!

Lakota historian Nick Estes talks about the violent origins of Thanksgiving and his book Our History Is the Future. “This history … is a continuing history of genocide, of settler colonialism and, basically, the founding myths of this country,” says Estes, who is a co-founder of the Indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe.

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: In this special broadcast, we begin the show with the Indigenous scholar and activist Nick Estes. He’s co-founder of the Indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe. His books include Our History Is the Future, which tells the history of Indigenous resistance over two centuries, offering a road map for collective liberation and a guide to fighting life-threatening climate change. Estes centers this history in the historic fight against the Dakota Access pipeline at Standing Rock. I asked him to talk about the two Thanksgiving stories he writes about at the beginning of his book.

NICK ESTES: So, the first Thanksgiving story is — begins with the Pequot massacre by members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which really marks sort of — in my opinion, marks sort of the mythology of the United States as a settler-colonial country founded on sort of genocide to create, ironically, peace. And then I begin with another story of a prayer march that we led in the Bismarck mall in Bismarck, North Dakota, to kind of bring attention to the Standing Rock struggle during a Black Friday shopping event, which was met by police armed with AR-15s, who then began punching and kicking water protectors who were holding a prayer in the Bismarck mall.

And I thought it was a really kind of jarring sort of contrast between, you know, the past and the present, to say that while there are sort of differences between the massacre of Pequots in Massachusetts to the contemporary sort of fight against an oil pipeline, nonetheless, you know, Bismarck, North Dakota, is a 90% white community that originally the Dakota Access pipeline was supposed to go upriver from, but then was rerouted downriver to disproportionately affect the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. And “disproportionate” is the language that the Army Corps of Engineers used, as if there’s ever a proportionate risk to environmental issues and water contamination. So, at this particular moment, there weren’t any actions that were happening in the camps, and it was largely at a standstill. And I think that Thanksgiving weekend, there was an Unthanksgiving feast that was held in the camps, and it was actually the highest point of the camps themselves, in the sense that there were the most sort of water protectors had showed up. So, I thought it was a good kind of contrast to show that this history, you know, is a continuing history of genocide, of settler colonialism and, basically, the founding myths of this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Your book’s last words are, “[W]e are challenged not just to imagine, but to demand the emancipation of earth from capital. For the earth to live, capitalism must die.” Explain.

NICK ESTES: So, that line is part of this longer section on liberation. And I think when we think about climate change, oftentimes the question of climate change really centers on market-driven solutions, such as, you know, green capitalism, and how do we create markets that sort of incentivize transition to sustainable economies, right? And I think, really, what we’re kind of like beating around the bush is, is that it’s the system of capitalism that led us into this economic crisis to begin with. It’s the sort of designation of certain populations in certain territories as disposable, that has led us into our current epoch of global climate change. And so, when we talk about who’s going to bear the most burden when we transition, you know, out of the carbon economy, it most likely is going to be those populations that have historically been colonized, you know.

And, you know, what’s happening in southeast Africa is a perfect example of why we need to transition away from not just the carbon economy, but capitalist economies in general, because if we look at the history of how Africa has been a resource colony for Europe and for North America, we can look internally in the United States and understand that Indigenous nations continue to serve as resource colonies for the United States, whether it’s the Navajo Nation, where I’m living right now, that is producing oil and coal to generate electricity for the Southwest region, or whether it’s the Fort Berthold Reservation up in North Dakota, that is, you know, ground zero for oil and gas development in the Bakken region. We have to understand that Indigenous nations have largely been turned into resource colonies and sites of sacrifice for not just the United States, but for the oil and gas industry.

And so we need to not just think beyond climate change and putting carbon into the atmosphere, but we actually need to think about the system, the social system — right? — that created those conditions in the first place. And so, capitalism is fundamentally a social relation. It’s a profit-driven system, whereas Indigenous sort of ways of relating is one about reciprocity and a mutual sort of respect, not just with the human, but also with the nonhuman world. And we’re undergoing, you know, the sixth mass — sixth massive extinction event, which is caused by not just climate change, but is caused by capitalist sort of systems and the profit-driven sort of motive of our current economic and social system.

AMY GOODMAN: Nick Estes, you focus on seven historical moments of resistance in your new book, Our History Is the Future. You say they form a historical road map for collective liberation. How did you choose these histories? Just quickly take us through them.

NICK ESTES: Sure. So, I begin at the camps. I begin in the present, you know, at Standing Rock. And then I go to the fur trade with the first U.S. invasion, which was Lewis and Clark, who came through — who trespassed through our territory and were stopped by our leadership. And then I go through the Indian Wars of the 19th century and the buffalo genocide. And then I go into talking about the damming of the Missouri River in the mid-20th century, and then looking at Red Power in the 1960s and in the 1970s and how all of these Indigenous people, who were relocated because their lands were flooded by these dams, eventually found themselves and created sort of the modern Indigenous movement, known as Red Power, and then looking — going back and ending actually at Standing Rock in 1974, with the creation of the International Indian Treaty Council, which really coalesced these generations of Indigenous resistance and took the treaties, the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, to the world and to the United Nations. And to do that, they looked to Palestinians, they looked to the South African anti-apartheid movement, who provided the mechanisms for recognition of Indigenous rights at the United Nations. And that all resulted, over four decades, in the touchstone document, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was passed by the U.N. in 2007.

And so, in many ways, when we look at Standing Rock, and we look at — if we go down flag row and we see the hundreds of tribal nation flags that were represented in 2016 and 2017, we also saw the Palestinian flag that was there, kind of hearkening back to that international solidarity with movements of the Global South, and specifically our Palestinian relatives, who, you know, today are still facing — much like us, are still facing the brunt and the brutality of settler colonialism, whether it’s, you know, the United States recognizing the annexation of the Golan Heights or whether it’s, you know, here in North America and the continued dispossession of Indigenous territory and rights. We can see that settler colonialism in Israel — or, in Palestine, is really an extension of settler colonialism in North America.

And so — and then I end, you know, with — back at the camps and looking at how these camps really provided — you know, I actually look at a physical map that was handed out to water protectors who came to the camp. And on that map there was, you know, where to find food, where to find the clinics — right? — and where to find the security, and all the camps that were represented at Standing Rock. And, to me, that provided, you know, a kind of interesting parallel to the world that surrounded the camps, which was 90 — you know, some 92 different law enforcement jurisdictions. You had the North Dakota National Guard, the world of cops, the world of the militarized sort of police state. And in the camps themselves you had sort of the primordial sort of beginnings of what a world premised on Indigenous justice might look like. And in that world, you know, everyone got free food. There was a place for everyone. You know, the housing, obviously, was transient housing and teepees and things like that, but then also there was health clinics to provide healthcare, alternative forms of healthcare, to everyone. And so, if we look at that, it’s housing, education — all for free, right? — a strong sense of community. And for a short time, there was free education at the camps, right? Those are things that most poor communities in the United States don’t have access to, and especially reservation communities.

But given the opportunity to create a new world in that camp, centered on Indigenous justice and treaty rights, society organized itself according to need and not to profit. And so, where there was, you know, the world of settlers, settler colonialism, that surrounded us, there was the world of Indigenous justice that existed for a brief moment in time. And in that world, instead of doing to settler society what they did to us — genociding, removing, excluding — there’s a capaciousness to Indigenous resistance movements that welcomes in non-Indigenous peoples into our struggle, because that’s our primary strength, is one of relationality, one of making kin, right?

AMY GOODMAN: Nick, explain your title, Our History Is the Future.

NICK ESTES: So, that has two meanings. The first meaning is sort of a negative meaning, in the sense that the Oceti Sakowin, the Great Sioux Nation, has undergone several apocalypses. Going back to the fur trade and the annihilation of fur-bearing animals in our region, going back to the annihilation of the buffalo to take the land and to starve us into surrender, going back to the mid-20th century damming of the Missouri River, and now the North American sort of oil boom, these are different rounds of dispossession that we see in a long continuum, right? And while history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself, there’s echoes, that the United States has bailed itself out largely at the expense of Indigenous peoples and Indigenous lands. And so, in many ways, what we’re trying to prevent is that history in the future.

But the other, more sort of positive and generative aspect of that is, our history is the future in the sense that we have a long tradition of resistance to these sort of U.S.-imposed climate catastrophes on our own community. And we draw from the resistance movements, going back to the first time we halted the trespass of Lewis and Clark through our territories and said, “No, we are a sovereign nation. We have protection — we are the protectors of the Missouri River,” going back to the 19th century Indian Wars. And then, you know, my grandparents were water protectors in their own right, because they fought for and tried to defend the Missouri River by preventing the construction of the Pick-Sloan dams in the 1950s and the 1960s. And so, in many ways, I am just a product of my ancestors’ resistance. They were water protectors before. And we have a new generation of water protectors now.

AMY GOODMAN: Nick Estes, Indigenous scholar and activist, speaking in 2019. His books include Our History Is the Future. He’s co-founder of the Indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe.

Lakota historian Nick Estes talks about the violent origins of Thanksgiving and his book Our History Is the Future. “This history … is a continuing history of genocide, of settler colonialism and, basically, the founding myths of this country,” says Estes, who is a co-founder of the Indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe.

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: In this special broadcast, we begin the show with the Indigenous scholar and activist Nick Estes. He’s co-founder of the Indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe. His books include Our History Is the Future, which tells the history of Indigenous resistance over two centuries, offering a road map for collective liberation and a guide to fighting life-threatening climate change. Estes centers this history in the historic fight against the Dakota Access pipeline at Standing Rock. I asked him to talk about the two Thanksgiving stories he writes about at the beginning of his book.

NICK ESTES: So, the first Thanksgiving story is — begins with the Pequot massacre by members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which really marks sort of — in my opinion, marks sort of the mythology of the United States as a settler-colonial country founded on sort of genocide to create, ironically, peace. And then I begin with another story of a prayer march that we led in the Bismarck mall in Bismarck, North Dakota, to kind of bring attention to the Standing Rock struggle during a Black Friday shopping event, which was met by police armed with AR-15s, who then began punching and kicking water protectors who were holding a prayer in the Bismarck mall.

And I thought it was a really kind of jarring sort of contrast between, you know, the past and the present, to say that while there are sort of differences between the massacre of Pequots in Massachusetts to the contemporary sort of fight against an oil pipeline, nonetheless, you know, Bismarck, North Dakota, is a 90% white community that originally the Dakota Access pipeline was supposed to go upriver from, but then was rerouted downriver to disproportionately affect the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. And “disproportionate” is the language that the Army Corps of Engineers used, as if there’s ever a proportionate risk to environmental issues and water contamination. So, at this particular moment, there weren’t any actions that were happening in the camps, and it was largely at a standstill. And I think that Thanksgiving weekend, there was an Unthanksgiving feast that was held in the camps, and it was actually the highest point of the camps themselves, in the sense that there were the most sort of water protectors had showed up. So, I thought it was a good kind of contrast to show that this history, you know, is a continuing history of genocide, of settler colonialism and, basically, the founding myths of this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Your book’s last words are, “[W]e are challenged not just to imagine, but to demand the emancipation of earth from capital. For the earth to live, capitalism must die.” Explain.

NICK ESTES: So, that line is part of this longer section on liberation. And I think when we think about climate change, oftentimes the question of climate change really centers on market-driven solutions, such as, you know, green capitalism, and how do we create markets that sort of incentivize transition to sustainable economies, right? And I think, really, what we’re kind of like beating around the bush is, is that it’s the system of capitalism that led us into this economic crisis to begin with. It’s the sort of designation of certain populations in certain territories as disposable, that has led us into our current epoch of global climate change. And so, when we talk about who’s going to bear the most burden when we transition, you know, out of the carbon economy, it most likely is going to be those populations that have historically been colonized, you know.

And, you know, what’s happening in southeast Africa is a perfect example of why we need to transition away from not just the carbon economy, but capitalist economies in general, because if we look at the history of how Africa has been a resource colony for Europe and for North America, we can look internally in the United States and understand that Indigenous nations continue to serve as resource colonies for the United States, whether it’s the Navajo Nation, where I’m living right now, that is producing oil and coal to generate electricity for the Southwest region, or whether it’s the Fort Berthold Reservation up in North Dakota, that is, you know, ground zero for oil and gas development in the Bakken region. We have to understand that Indigenous nations have largely been turned into resource colonies and sites of sacrifice for not just the United States, but for the oil and gas industry.

And so we need to not just think beyond climate change and putting carbon into the atmosphere, but we actually need to think about the system, the social system — right? — that created those conditions in the first place. And so, capitalism is fundamentally a social relation. It’s a profit-driven system, whereas Indigenous sort of ways of relating is one about reciprocity and a mutual sort of respect, not just with the human, but also with the nonhuman world. And we’re undergoing, you know, the sixth mass — sixth massive extinction event, which is caused by not just climate change, but is caused by capitalist sort of systems and the profit-driven sort of motive of our current economic and social system.

AMY GOODMAN: Nick Estes, you focus on seven historical moments of resistance in your new book, Our History Is the Future. You say they form a historical road map for collective liberation. How did you choose these histories? Just quickly take us through them.

NICK ESTES: Sure. So, I begin at the camps. I begin in the present, you know, at Standing Rock. And then I go to the fur trade with the first U.S. invasion, which was Lewis and Clark, who came through — who trespassed through our territory and were stopped by our leadership. And then I go through the Indian Wars of the 19th century and the buffalo genocide. And then I go into talking about the damming of the Missouri River in the mid-20th century, and then looking at Red Power in the 1960s and in the 1970s and how all of these Indigenous people, who were relocated because their lands were flooded by these dams, eventually found themselves and created sort of the modern Indigenous movement, known as Red Power, and then looking — going back and ending actually at Standing Rock in 1974, with the creation of the International Indian Treaty Council, which really coalesced these generations of Indigenous resistance and took the treaties, the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, to the world and to the United Nations. And to do that, they looked to Palestinians, they looked to the South African anti-apartheid movement, who provided the mechanisms for recognition of Indigenous rights at the United Nations. And that all resulted, over four decades, in the touchstone document, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was passed by the U.N. in 2007.

And so, in many ways, when we look at Standing Rock, and we look at — if we go down flag row and we see the hundreds of tribal nation flags that were represented in 2016 and 2017, we also saw the Palestinian flag that was there, kind of hearkening back to that international solidarity with movements of the Global South, and specifically our Palestinian relatives, who, you know, today are still facing — much like us, are still facing the brunt and the brutality of settler colonialism, whether it’s, you know, the United States recognizing the annexation of the Golan Heights or whether it’s, you know, here in North America and the continued dispossession of Indigenous territory and rights. We can see that settler colonialism in Israel — or, in Palestine, is really an extension of settler colonialism in North America.

And so — and then I end, you know, with — back at the camps and looking at how these camps really provided — you know, I actually look at a physical map that was handed out to water protectors who came to the camp. And on that map there was, you know, where to find food, where to find the clinics — right? — and where to find the security, and all the camps that were represented at Standing Rock. And, to me, that provided, you know, a kind of interesting parallel to the world that surrounded the camps, which was 90 — you know, some 92 different law enforcement jurisdictions. You had the North Dakota National Guard, the world of cops, the world of the militarized sort of police state. And in the camps themselves you had sort of the primordial sort of beginnings of what a world premised on Indigenous justice might look like. And in that world, you know, everyone got free food. There was a place for everyone. You know, the housing, obviously, was transient housing and teepees and things like that, but then also there was health clinics to provide healthcare, alternative forms of healthcare, to everyone. And so, if we look at that, it’s housing, education — all for free, right? — a strong sense of community. And for a short time, there was free education at the camps, right? Those are things that most poor communities in the United States don’t have access to, and especially reservation communities.

But given the opportunity to create a new world in that camp, centered on Indigenous justice and treaty rights, society organized itself according to need and not to profit. And so, where there was, you know, the world of settlers, settler colonialism, that surrounded us, there was the world of Indigenous justice that existed for a brief moment in time. And in that world, instead of doing to settler society what they did to us — genociding, removing, excluding — there’s a capaciousness to Indigenous resistance movements that welcomes in non-Indigenous peoples into our struggle, because that’s our primary strength, is one of relationality, one of making kin, right?

AMY GOODMAN: Nick, explain your title, Our History Is the Future.

NICK ESTES: So, that has two meanings. The first meaning is sort of a negative meaning, in the sense that the Oceti Sakowin, the Great Sioux Nation, has undergone several apocalypses. Going back to the fur trade and the annihilation of fur-bearing animals in our region, going back to the annihilation of the buffalo to take the land and to starve us into surrender, going back to the mid-20th century damming of the Missouri River, and now the North American sort of oil boom, these are different rounds of dispossession that we see in a long continuum, right? And while history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself, there’s echoes, that the United States has bailed itself out largely at the expense of Indigenous peoples and Indigenous lands. And so, in many ways, what we’re trying to prevent is that history in the future.

But the other, more sort of positive and generative aspect of that is, our history is the future in the sense that we have a long tradition of resistance to these sort of U.S.-imposed climate catastrophes on our own community. And we draw from the resistance movements, going back to the first time we halted the trespass of Lewis and Clark through our territories and said, “No, we are a sovereign nation. We have protection — we are the protectors of the Missouri River,” going back to the 19th century Indian Wars. And then, you know, my grandparents were water protectors in their own right, because they fought for and tried to defend the Missouri River by preventing the construction of the Pick-Sloan dams in the 1950s and the 1960s. And so, in many ways, I am just a product of my ancestors’ resistance. They were water protectors before. And we have a new generation of water protectors now.

AMY GOODMAN: Nick Estes, Indigenous scholar and activist, speaking in 2019. His books include Our History Is the Future. He’s co-founder of the Indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe.