To Desegregate, Ride the Bus

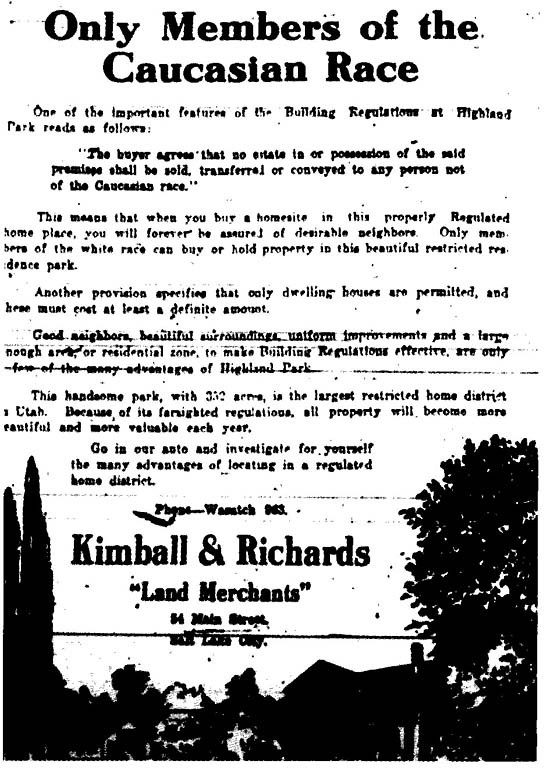

Banner photo by Adam E. Moreira, CC BY-SA 3.0 unported. Copy of Kimball & Richards advertisement from elycefeliz via Flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Rosa Parks took a seat to take a stand. These days, prejudice pushes people into bus seats, not out of them.

The descendants of Europeans wouldn’t even think of letting go of their cars, for car commuting “rules the roads outside the city.” They say it’s just not possible to take the bus out here. You’re really car-dependent.

Behold our inherent vulnerability in a social system focused on the primacy of private cars over public transit.

Car-dependent.

And still, somehow, the bigger your car, the tougher you are. Are you? Take the bus, buttercup. Sit down with folk who make your lifestyle possible every day.

But most suburbanites couldn’t tell you which bus route comes closest to their home. Why should they? After all, stepping onto the bus and joining the human race puts you at the mercy of those patchy schedules and dreary waits so emblematic of U.S. public transit. Who rides the bus to and from downtown Philadelphia? Those who must.

Here, a few miles west of Philadelphia, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) winds down its daily service much too early to serve suburbanites even for the odd night out. Who wants to dart away in the middle of a play’s second act to catch the last train before it’s gone? Even getting a bus ride into the city is iffy. Occasionally, because this is SEPTA in suburbia, the bus doesn’t come. How long until the next scheduled bus? A half-hour? An hour? Check the app. It might be right. It might be wrong. Don’t ask why; just wait there in the traffic and the slush or the heat, and speaking of heat, global heating is magnifying the summer sun something fierce, so the people you mainly don’t see on the buses in suburbia are the suburbanites.

The 1920s: Do You Know Where Your Ancestors Are?

In 1927, 44 homeowners on West Penn Street in northwest Philly agreed to exclude any new residents “other than those of the Caucasian race.” Others would be subject to eviction by force of arms.

Noxious restrictions oozed outward, through the stately suburbs of the Main Line—such as Haverford Township, where just 3% of residents are African-American today. In nearby Ardmore, developers insulated their clientele by building roads around the area where Black people settled.

Racial exclusion became a marketing theme. Developers touted racial deed restrictions as protections for property values.

The National Association of Real Estate Boards joined with the U.S. Department of Commerce to provide a model race restriction that developers could use. Homeowner associations and real estate brokers followed suit. In and around Spokane, Denver, Cincinnati, and slews of other cities, exclusionary deed language maintained segregation.

Racial deed restrictions kept coming even after the Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional in 1948. And the Federal Housing Administration relied upon these exclusions when insuring home loans until 1962. The FHA preferred loans for new houses in the suburbs over existing properties in the cities. As urban properties languished, suburban real estate flourished.

The federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 banned housing discrimination. States soon legislated accordingly, preventing developers from writing racist deed language into the public records. And still the language lingered on the older deeds. Millions of them.

A deed covenant is legally indelible, buyers were always told. Don’t worry; racial covenants can’t be enforced. Only in the last few years have states changed their views. Arizona adopted a deletion process; Virginia offers deed-scrubbing workshops. As of July 1, 2024, county deed recorders in Kansas can certify releases of race-based exclusions, for a fee. The new Kansas law also directs homeowner associations to remove racial covenants from their governing documents.

From 2016 to 2020, Mapping Prejudice, an initiative based at the University of Minnesota, found 8,000 racial covenants in Minneapolis. Now, the state lets deed holders renounce them. In 2021, California started redacting racial covenants. A county clerk successfully pressed Oregon to do likewise in 2024.

Speaking of Oregon, the bill of rights for its constitution (ratified 1857) contained a racial exclusion for the entire state:

“No free negro or mulatto not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside or be within this state or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein…”

In the words of Matt Novak, Oregon was explicitly founded as a kind of white utopia. This was in line with the Oregon Territorial Legislature’s earlier exclusion law, whose preamble opined that “it would be highly dangerous to allow free Negroes and mulattoes to reside in the territory to intermix with Indians, instilling in their minds feelings of hostility against the white race.”

The 2020s: Do We Live in a Sundown Town?

Phyllis Raybin Emert writes about the warning signs: “Whites Only Within City Limits After Dark.” “God Help You If the Sun Ever Sets on You Here!” Some towns’ signage used the N word.

Emert points to James W. Loewen’s Sundown Towns – A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. In thousands of U.S. towns, from 1890 to 1968, Blacks would be arrested or harrassed after dusk. In effect, this restricted the ability of Black people to travel by car.

In some areas, existing Black households would be chased out, their land seized. Some owned hundreds of acres they’d never get back.

In 1968, Carol Jenkins, a 21-year-old with a new job selling encyclopedias door-to-door, was stabbed to death with a screwdriver in an Indiana sundown town. Emert observes that Ferguson, Missouri, where police officer Darren Wilson killed 18-year-old Michael Brown, was a sundown town from 1940 to 1960. Examining the context of Brown’s death in 2014, the U.S. Justice Department found deep patterns of racism in Ferguson, where Black residents were disproportionately targeted through arrests and fines.

Levittown too was a sundown town. I first heard about William Levitt in a sociology course, when the prof discussed the planning of U.S. suburbs after World War II. What never appeared in our course materials was Levittown’s history of exclusion. Levittown mortgages and leases were limited to “Caucasians” and their “domestic servants.” To defend this, the famous developer resorted to “the plain fact” that “most whites prefer” segregation. Even after removing the restrictive clauses, Alan Singer observes, Levitt and Sons still turned away Blacks.

In short, decades of opportunity-hoarding shaped the maps of generations, including mine and yours. (When SEPTA winds down its daily service, who is in for the night, and who is out?)

One reason for what “most whites prefer” involves real estate values, as William Levitt knew well. Owners of expensive homes fund high-achieving school districts, perpetuating the wealth divide. And now, who is positioned to come up with the down payments needed to buy homes?

The Urban Institute observed in 2024 that the “Black homeownership rate is lower than it was in 2000 (44.3 versus 45.7 percent), and the Black-white homeownership gap is wider than it was when segregation was legal.” Let’s keep this in mind when we hear Trump promise to guard single-family zoning in the suburbs (and, lest we forget, to protect suburban women).

“Nonminorities have brought about many of the problems that minorities encounter”, as the Report of the Oregon Supreme Court Task Force on Racial/Ethnic Issues in the Judicial System stated in 1994. Mere lip service, the Oregon State Bar observed in its vivid response, doesn’t resolve those problems; we must commit to an active search for truth and vision.

Centuries of financial inequality, imposed to benefit the group in charge, have shaped today’s bus ridership. They’ve shaped the routes where people go when they’re going home. They’ve shaped human interactions daily. They’ve shaped people’s health—research links areas with race-based deed restrictions to overheating hazards. Heat extremes kill. And this brings us back to the car. One major reason for global heating, of course, is the car.

Understanding, followed up by action, could bring people together. But first it would inconvenience the people who’ve benefited most from segregation, people imagining that private cars will continue to rule the roads—albeit on battery power.

Can we actively support a better idea? A collective kind of problem-solving? A system redirected, by public participation, to bring communities together by offering comfortable transit to everyone? Tack this onto your new year’s resolutions:

Ride the bus.