Imperialism: ‘Antagonistic cooperation’ or antagonistic contradictions? A reply to Promise Li

As I noted in my reply to Argentine economist Claudio Katz, the debate among Marxists about imperialism theory has intensified in the past few years.1 A few weeks ago, another socialist writer, Promise Li, published a further contribution to this debate.2 Li is a socialist from Hong Kong now based in Los Angeles, where he is active as a member of Tempest Collective and Solidarity.

His contribution is an elaboration of his concept of imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation,” which he delineates, on one hand, from those who consider the “US Empire” as the only imperialist force and, on the other hand, from those who support Lenin’s orthodox theory of imperialism. As Li refers to me (correctly) as a supporter of the latter camp, I would like to respond to his criticism. I shall illustrate — both methodologically as well as empirically — that imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation” does not allow us to understand the dynamics of the current world situation.

As this is a wide topic, I will try to limit myself to the specific arguments and criticism presented by Li. For a more comprehensive elaboration of my understanding of the Marxist theory of imperialism, I refer readers to previous works.3

Li’s concept of imperialism as ‘antagonistic cooperation’

First, I would like to note that Li, in contrast to various other contributors to the debate, consistently rejects any accommodation to Chinese imperialism. As he noted in an interview, “the left must focus on building links between those resisting US and Chinese imperialisms.”4 Hence, he positively delineates himself from (proto-)Stalinist writers who adhere to a one-eyed anti-imperialism that strongly denounces the crimes of Washington but is very restrained when it comes to the crimes of Beijing and Moscow. No doubt, Li’s first-hand experience with the brutal reality of the Xi Jinping regime in Hong Kong has been pretty helpful for his understanding.

Nevertheless, his concept of imperialism is problematic as he downplays the accelerating inter-imperialist rivalry and overestimates the stability and cooperation between Great Powers. In contrast, I consider the capitalist world system as one which is in long-term decline. In such a period, the contradictions between imperialist powers in West (US, Western Europe and Japan) and East (China and Russia) as well as between these powers and semi-colonial countries cannot but intensify. Imperialism is not a system characterised by “antagonistic cooperation” but rather by antagonistic contradictions.

Before discussing the flaws of imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation”, I will start with a summary of Li’s presentation. He relates the origins of his theory to the writings of German communist August Thalheimer and Nikolai Bukharin, a leading Bolshevik theorist. The concept of imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation” was later revisited by the Brazilian Marxist collective Política Operária (POLOP) to which belonged, among others, Ruy Mauro Marini, most known for his theory of sub-imperialism.

I note in passing that the theory of sub-imperialism, like the concept of “antagonistic cooperation”, lacks a dialectical approach. However, at this point I will not discuss this issue and refer readers to other works in which I deal with the theory of sub-imperialism.5

Starting from this methodological basis, Li applies the concept to analyse the imperialist world order today.

[W]e can modify Thalheimer’s definition and consider antagonistic cooperation a particular stage of imperialism in which the terms for competition between national capitals take shape through or are mediated by the “interpenetration of mutual imperial interests and domains,” rather than cooperation and competition as distinct tendencies.

The author emphasises the relative stability of the capitalist world system. Of course, he recognises its repeated crisis, however, he thinks that the tendency towards cooperation between the powers is prevailing:

Without downplaying the ever-present threat of antagonistic crises and rivalries between states, this analysis foregrounds the capacity of the imperialist world system to maintain cooperative dynamics to maximize paths for global accumulation.

Consequently, Li delineates his concept from other theories such as, on one hand, that a “US-led Empire” dominates the world and, on the other hand, the orthodox Marxist theory of imperialism.

[W]e must not miss capitalism’s readjustment of its own constitution to develop new terms for recovery and stabilization. Antagonistic cooperation, a conceptual framework developed by Marxists in postwar Germany and Brazil, provides the best tools for analyzing this particular stage of imperialism. Unlike the unipolar theorization of Tricontinental or the multipolar rivalry of those following the Bolshevik theorists, which both overemphasize rivalry between imperialist powers, antagonistic cooperation understands the imperialist system as an interdependent totality that can accommodate interdependence between and beyond geopolitical blocs. Additionally, unlike the two models described above, antagonistic cooperation also allows for heterogeneity of power relations within this paradigm even as the overall structure of dependency between core and periphery economies continues to exist. For one, the rivalry between the United States and China does not imply their equality in the global imperialist system, which is still led and dominated by the former. What Claudio Katz calls “empires-in-formation,” and other intermediate or subimperial countries, are also cultivating the ability to occasionally check US power through military, economic, or other means. But this signals neither an anti-imperialist affront to US hegemony nor a straightforward leveling of the playing field as a new terrain of interimperialist rivalry.

Economic interdependence has shown surprising resilience even across rival geopolitical blocs. Existing theories of imperialism fail to fully account for these seemingly contradictory dimensions of today’s world system. Tricontinental theorizes the current stage of imperialism as “hyper-imperialism,” characterized by a unipolar “US-Led Military Bloc” as the sole imperialist force that renders all other global contradictions secondary or “non-antagonistic.” For the authors at Tricontinental, this imperialist bloc is being challenged by a multipolar “socialist grouping led by China,” representing “growing aspirations for national sovereignty, economic modernization, and multilateralism, emerging from the Global South.” Such a perspective disregards the implications of both the interdependence between the two blocs and the emergent role of certain intermediate economies — for example, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia — in developing regional hegemonies that facilitate imperialism amidst geopolitical tensions.

In contrast to Tricontinental, some see the form of imperialism today as an interimperialist conflict in the same vein as the First World War, which Bolshevik revolutionaries V. I. Lenin and Nikolai Bukharin first theorized. This view overly downplays the decline of US hegemony while overestimating the rise of new imperialists as a counterbalance to US imperialism. These faulty conceptions are two sides of the same coin: they overstate the dynamics of rivalry, thus obscuring salient sites of interconnection in the imperialist system that can yield powerful opportunities for solidarity across antisystemic struggles.

Thalheimer and Bukharin: Pioneers of the concept of ‘antagonistic cooperation’?

Who were Bukharin and Thalheimer? Bukharin joined the Bolsheviks as a young and dedicated militant and worked in the Moscow underground party before joining other Russian revolutionaries in exile. He became a Bolshevik leader in 1917 and was a key figure in shaping the party’s policy in the first decade after the revolution. Bukharin was a gifted theoretician who repeatedly clashed with Lenin on issues such as imperialism, the state and the national question. Nevertheless, he was a thoughtful and inspiring Marxist intellectual and Lenin appreciated his work, even calling him “the darling of the party”.

While Bukharin was initially a spokesperson for the ultra-left wing in the party, he joined Stalin’s faction in 1923 and played a crucial role in theorising the opportunist strategy of the Comintern, the pro-Kulak policy of the regime and as the expulsion of the Left Opposition, which was led by Leon Trotsky. Soon after the repression of the authentic Bolsheviks in late 1927, the Stalinist bureaucracy — facing economic crisis as a result of their past pro-Kulak policy — turned towards the forced collectivisation of the peasantry and super-industrialisation. Consequently, Stalin — whom Bukharin now realised to be a “new Genghis Khan” — kicked out the former “darling of the party”. However, in contrast to the Trotskyists, Bukharin and his supporters refrained from launching an opposition struggle and quickly capitulated to Stalin. This was the end of Bukharin as an independent politician and a few years later, during the horrific show trials in 1936-38, they were all shot.6

August Thalheimer was part of the left-wing of German social democracy before 1914, who joined the Spartacus League of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht during World War I. He became the Communist Party’s leading theoretician in 1921 when he and Heinrich Brandler took over the leadership. However, as they miserably failed in the revolutionary situation in the second half of 1923 (the “German October”), they had to retreat from leadership functions. After the downfall of their intellectual mentor Bukharin in 1928, Brandler and Thalheimer formed the so-called international Right Opposition, which only criticised the Stalinists for its ultra-left (but not its opportunist) mistakes and failed to call for an opposition struggle against the regime. Worse, they fully supported the arch-opportunist people’s front policy in the mid-1930s and refused to condemn the Moscow show trials. Unsurprisingly, the international Right Opposition crumbled in the late 1930s and only a small group continued to exist in Germany after World War II.7

Despite their methodological failings, Bukharin and Thalheimer (the first much more than the latter) were serious theoreticians who made a number of thoughtful contributions.

Like Li, the POLOP collective base their concept of imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation” on a German-language pamphlet by Thalheimer, Grundlinien und Grundbegriffe der Weltpolitik nach dem 2. WeItkrieg (Basic Principles and Concepts of World Politics after World War II), which was published in 1946. In this pamphlet, the German Communist called the imperialist alliance led by the US as “antagonistic cooperation”.

While it is true that this term originates from Thalheimer’s pamphlet, both POLOP and Li’s reference to this document is highly problematic. In this work, the German communist viewed his term “antagonistic cooperation” as a description of the situation after WWII. But he recognised that the cooperation between imperialist powers was based on the overriding class contradictions between the Western powers and the expanding Stalinist camp, and on the absolute superiority of the US. Hence his analysis of inter-imperialist cooperation was based on these conjunctural features.

Consequently, Thalheimer’s view of the world order was not one of “cooperation” but rather of a looming World War III, as the imperialist alliance was based on collective aggression against the Stalinist camp (the degenerated workers’ states):

We have shown that factors that have caused the imperialists’ urge for territorial expansion do not result in war within the capitalist camp but rather primarily in imperialist cooperation to different degrees. Therefore, this urge for territorial expansion can only be directed externally: against the socialist sector, the Soviet Union and its sphere of influence.”

If these facts show anything it is, in the immediate aftermath of World War II, the ongoing general deployment for a new world war.8

However, Li’s understanding of the concept of “antagonistic cooperation” is different. Such cooperation can no longer be based on a common policy of aggression against a joint enemy since the Soviet Union and its allies no longer exist. Hence, Li views “antagonistic cooperation” as a new stage of imperialism — independent of the existence of a common enemy that could keep the imperialist powers united. In contrast, Thalheimer elaborated his concept of “antagonistic cooperation” as a conjunctural description of a specific situation caused by the peculiar features of the outcome of World War II. For the German Communist, such a situation of “antagonistic cooperation” would not longer exist when the common enemy had disappeared.

Likewise, Bukharin's peculiar analysis of imperialism, certainly not without flaws, did not come close to the concept of “antagonistic cooperation” advocated by Li. Far from assuming a relatively stable world or even a prevailing cooperation between Great Powers, Bukharin viewed imperialism as an antagonistic system characterised by sharp inter-imperialist rivalry and a tendency towards war:

From the point of view of the ruling circles of society, frictions and conflicts between "national" groups of the bourgeoisie, inevitably arising inside of present-day society, lead in their further development to war as the only solution of the problem. We have seen that those frictions and conflicts are caused by the changes that have taken place in the conditions of reproducing world capital. Capitalist society, built on a number of antagonistic elements, can maintain a relative equilibrium only at the price of painful crises.9

The transition to a system of finance capitalism constantly reinforced the process whereby simple market, horizontal, competition was transformed into complex competition. Since the method of struggle corresponds to the type of competition, this was inevitably followed by the ‘aggravation’ of relations on the world market. Methods of direct pressure accompany vertical and horizontal competition, therefore the system of world finance capital inevitably involves an armed struggle between imperialist rivals. And here lies the fundamental roots of imperialism. … The conflict between the development of the productive forces and the capitalist relations of production must - so long as the whole system does not blow up - temporarily reduce the productive forces so that the next cycle of their development might then begin in the very same capitalist carapace. This destruction of the productive forces constitutes the conditions sine qua non of capitalist development and from this point of view crises, the costs of competition and - a particular instance of those costs - wars are the inevitable faux frais of capitalist reproduction.10

Bukharin — in contrast to Li — did not view the internationalisation of capitalist production and reproduction as a feature that would limit inter-imperialist tensions. Instead, he understood it as a development that would accelerate conflicts between Great Powers:

The international division of labour, the difference in natural and social conditions, are an economic prius which cannot be destroyed, even by the World War. This being so, there exist definite value relations and, as their consequence, conditions for the realization of a maximum of profit in international transactions. Not economic self-sufficiency, but an intensification of international relations, accompanied by a simultaneous "national" consolidation and ripening of new conflicts on the basis of world competition — such is the road of future evolution.11

Hence, the Bolshevik theoretician characterised war as an “immanent law” of imperialism:

War in capitalist society is only one of the methods of capitalist competition, when the latter extends to the sphere of world economy. This is why war is an immanent law of a society producing goods under the pressure of the blind laws of a spontaneously developing world market, but it cannot be the law of a society that consciously regulates the process of production and distribution.12

In summary, Li and the POLOP’s reference to Thalheimer and Bukharin as pioneers of the concept of “antagonistic cooperation” lacks justification.

A flawed methodological basis: Bukharin’s undialectical theory of equilibrium

Having said this, we do not deny that Li is partly justified in relying on Bukharin and Thalheimer, because imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation” shares certain methodological similarities with these two theoreticians. Namely, they all embrace — consciously or unconsciously — the mechanist equilibrium theory, which is devoid of dialectics.

Li’s “analysis foregrounds the capacity of the imperialist world system to maintain cooperative dynamics to maximize paths for global accumulation.” Likewise, he approvingly quotes another writer saying that “cooperation [between the imperialists] for the maintenance of the system prevails“:

As [Jeffrey] Sachs writes: ‘Antagonistic cooperation does not free the capitalist world from internal shocks at all levels, ups and downs. There are moments when antagonism seems to predominate, when the national bourgeoisies threaten an “independent” foreign policy, rebel against the schemes of the International Monetary Fund, and nationalize particularly unpopular foreign companies. The same phenomenon occurs among the imperialist powers themselves in moments of periodic relaxation of international tension. It disappears when there is a new upsurge in international tension and, as in France in 1968, when the capitalist regime is put in check. In the long run, cooperation for the maintenance of the system prevails.’

Bukharin disagreed with any view of the imperialist world as one of cooperation, but he did sympathise with the philosophical teachings of Alexander Bogdanov, who opposed dialectical materialism and elaborated a system called “organizational philosophy”. Bogdanov was a leading figure among the Bolsheviks in 1904-08, but Lenin waged a fierce struggle against him and his philosophy when political differences — Bogdanov combined idealist philosophy with support for ultra-left politics after the defeat of the first Russian Revolution in 1905-07 — threatened to paralyse the party. Lenin’s famous philosophical work Materialism and Empirio-criticism is a polemic against Bogdanov’s philosophy.13

Bukharin — about whom Lenin noted in his testament that “he has never made a study of dialectics, and, I think, never fully appreciated it” — adopted Bogdanov’s equilibrium theory. This theory considers reality as a (relative, moving) equilibrium which, repeatedly, gets disrupted by sudden crisis but, after some time, restabilises as a new equilibrium. In other words, equilibrium is the natural position of order. In his book Historical Materialism, Bukharin expresses this view explicitly:

On the other hand, we have here also the form of this process: in the first place, the condition of equilibrium; in the second place, a disturbance of this equilibrium; in the third place, the reestablishment of equilibrium on a new basis. And then the story begins all over again: the new equilibrium is the point of departure for a new disturbance, which in turn is followed by another state of equilibrium, etc., ad infinitum.14

This does not mean that Bukharin ignored contradictions and the resulting motion as crucial driving forces of development. However, he viewed contradictions not so much as an internal, essential feature of all things (including an equilibrium) but rather as something external. This is because he ignored the unity of opposites and the struggle between its contradictory parts as a fundamental law for understanding matter and its motion. “Development is the ‘struggle’ of opposites,” as Lenin said.15 Hence, for Bukharin motion was not so much caused by internal contradictions but rather by contradictions between different things (equilibriums).

He wrote:

If, in a condition of growth, the structure of society should become poorer, i.e., its internal disorders grow worse, this would be equivalent to the appearance of a new contradiction: a contradiction between the external and the internal equilibrium, which would require the society, if it is to continue growing, to undertake a reconstruction, i.e., its internal structure must adapt itself to the character of the external equilibrium. Consequently, the internal (structural) equilibrium is a quantity which depends on the external equilibrium (is a “function” of this external equilibrium)....16

The precise conception of equilibrium is about as follows: “We say of a system that it is in a state of equilibrium when the system cannot of itself, i.e., without supplying energy to it from without, emerge from this state.”17

Bukharin did not explicitly deny the role of internal contradictions; he was too smart a Marxist intellectual for this. But despite his intentions, he systematically underestimated the decisive role of internal contradictions as the primary driving force of motion.

A materialist dialectic critique

The connection between the mechanist equilibrium theory of Bukharin and the concept of imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation” should be clear. The philosophy of downplaying the struggle of opposites and of internal contradictions causing motion results in an understanding of reality as a state of (moving) equilibrium. On such a methodological basis, one ends up easily viewing the world situation as primarily characterised by relative stability and cooperation between imperialists. As a result, one gets confused and can not recognise the direction of motion of world politics and economy.

The mechanist method is incapable of answering correctly a crucial question: what is the determining characteristic of matter — a state of equilibrium or contradiction and motion as a result of the struggle of opposites? From the point of view of materialist dialectic, the correct answer is that the struggle of opposites, contradiction, is the determining feature since it causes motion, transformation, progress. In contrast, the state of equilibrium is only a temporary moment. Hegel was right when he noted: “Contradiction is the root of all movement and vitality, and it is only insofar as it contains a Contradiction that anything moves and has impulse and activity.”18

This was also the understanding of Marx and Engels. The latter explained in his Anti-Dühring:

Motion is the mode of existence of matter. Never anywhere has there been matter without motion, nor can there be. Motion in cosmic space, mechanical motion of smaller masses on the various celestial bodies, the vibration of molecules as heat or as electrical or magnetic currents, chemical disintegration and combination, organic life — at each given moment each individual atom of matter in the world is in one or other of these forms of motion, or in several forms at once. All rest, all equilibrium, is only relative, only has meaning in relation to one or other definite form of motion... Matter without motion is just as inconceivable as motion without matter. Motion is therefore as uncreatable and indestructible as matter itself.19

Based on such an approach, Lenin emphasised in his article “On the Question of Dialectics” that motion and the struggle between opposites are absolute while stability and unity of opposites are relative:

The unity (coincidence, identity, equal action) of opposites is conditional, temporary, transitory, relative. The struggle of mutually exclusive opposites is absolute, just as development and motion are absolute.20

Materialist dialectic refuses to view equilibrium as the “normal” or “basic” condition of matter. It is rather a temporary stage in a long process of motion. Engels noted in his preliminary studies for his Dialectics of Nature:

[T]he individual motion strives towards equilibrium, the motion as a whole once more destroys the individual equilibrium… All equilibrium is only relative and temporary.21

It is now possible to better understand the category of equilibrium. Marxists do not deny the legitimacy of this category. But it must be understood properly. Motion does not take place in a vacuum. It is caused by the struggle of opposites. Such struggle can only take place if there is a relationship between these opposites. The totality of such relationships constitutes a kind of (temporary) equilibrium. But such a relationship is in constant motion because “reality is a process of creation and destruction,” as Abram Deborin, the leading philosopher of the great dialectical school that dominated philosophical discussions in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, noted.22

From the point of view of materialist dialectic, there exists a clear dialectical hierarchy. NA Karev, another leading philosopher of the Deborin school and supporter of Trotsky’s Left Opposition, explained in a critique of Bogdanov’s equilibrium theory:

Hence, Engels does not say at all that this or that state of equilibrium would not exist in reality. But they are provisional, they only constitute moments in the motion of matters, they make sense only in relation to this or that form of moments, they are the result of a limited motion. Hence, the states of equilibrium are subordinated and temporary moments in the process of motion and development. The fundamental and determining factor is the motion.23

Karev’s critique of Bogdanov also applies to imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation,” as advocated by Li and POLOP:

Bogdanov’s theory of equilibrium basically rests on the static point of view and not the dynamic one, as it recognizes the moment of static state as determining and not the moment of motion of a given body. The category of “moving” equilibrium does not solve the problem as it views mobility as a breach of the equilibrium and not the other way round — that the state of equilibrium is a provisional and relative moment of stability within the process of motion. The unity of equilibrium and motion is here understood by emphasizing the category of equilibrium while dialectic emphasizes the motion of a body, which is always and everywhere inherent to it.24

This brings us to the last point of our brief philosophical digression. Underestimating the centrality of struggle of opposites resulting in motion, and overemphasising the concept of equilibrium, results in an inability to assess the dynamic and direction of development. For a mechanist, who is fixated on the state of equilibrium, things appear as static. In reality, profound developments take place “below the surface,” which can only be recognised by dialectically approaching a given state of things (an “equilibrium”) as a temporary expression of motions caused by the struggle of opposites.

To give a simple analogy from daily life. If one is cooking water at home, one would not observe big changes most of the time. The water appears unvaried … until the final moments when it starts boiling. Does this mean that for 99% of the time, nothing is happening, and the water is just in a state of equilibrium? You do not need a degree in physics to know that this is not the case, but that a “hidden” process of heating has taken place.

Similarly, Marxists analysing developments in world politics and economy must not stop at observing only those phenomena that appear at the surface. They must look below the surface and identify the processes of accumulating contradictions in order to understand the direction of development with ruptures and explosions ahead. As Deborin once said: “First and foremost, a Marxist must determine the general direction of development.”25

This is only possible if one applies a materialist and dialectical method and avoids the doctrinaire schemas of mechanist equilibrium theory, which paint an illusionary picture of drowsy stagnation. Hegel noted that the method is the “soul and substance” and that “anything whatever is comprehended and known in its truth only when it is completely subjugated to the method.”26 Without the method of materialist dialectic, one cannot understand the dynamic of modern imperialism.

The mechanist method a la Bukharin obstructs recognition of the decay of capitalism and the accompanying processes of wars, revolutions and counterrevolutions.

Capitalism in the 21st century: Restoring its growth dynamic?

Li emphasises that elements of cooperation between imperialist powers (and with national bourgeoisies in the Global South) are prevailing. Likewise, while he recognises that capitalism is facing repeated crises, he believes it has shown the capacity to overcome these and restore growth (albeit, he says, this is not an automatic process but needs political intervention):

However, we must also not mistake this interdependence for an inert tendency of the system toward equilibrium. In reality, the maintenance of this cooperation requires continual upkeep, especially as the capitalist system is forced to address the repeating appearance of crises stemming from its internal contradictions. The crises of profitability in the 1970s and the 2000s, for example, required fundamental transformations in how capitalism is organized in order to restore growth (and the suppression of working-class insurgency). Thus, the terms for cooperation must be consciously reinvented to be maintained.

But in the mid-1970s, capitalism entered a long-term period of crisis — or a “curve of decline” to use a category from Trotsky’s concept of “curves of capitalist development” that he elaborated in 1923.27 This process of crisis has deepened since the Great Recession in 2008/09.28

Naturally such decay is not a linear process since capitalist reproduction proceeds in business cycles and countervailing tendencies exist. However, the tendency of decline prevails, as evidenced by numerous facts.

Most importantly, there exists a profound civilisation crisis reflected in the devastating climate change with catastrophic consequences for growing parts of humanity.29 Likewise, there is a clear tendency towards stagnation and decline in the capitalist world economy, resulting in growing waves of migration, social misery and more wars. Related is the accelerating militarisation and rivalry between imperialist powers. Two major wars — in the Middle East and Ukraine — involving Great Powers, directly or indirectly, and with the potential to spread to other countries are powerful examples for this.

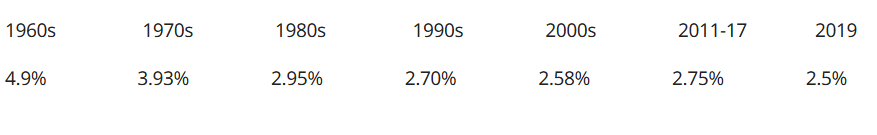

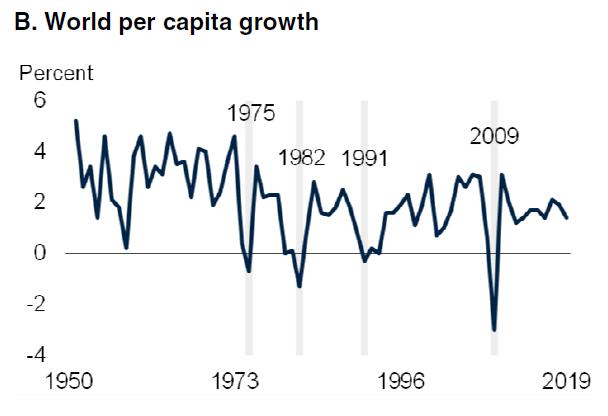

I have dealt with these issues elsewhere, so I will limit myself to presenting a few figures that demonstrate the declining dynamic of the capitalist world economy. Table 1 and Figure 1 show that there has been a continuous decline in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates — both in total as well as per capita — since the ’50s. These tables do not include figures for the Great Depression that started in late 2019, the worst slump since 1929.

Table 1: Average Annual Growth of Global GDP 1960-201930

Figure 1: Average Annual Growth of Global GDP Per Capita 1950-201931

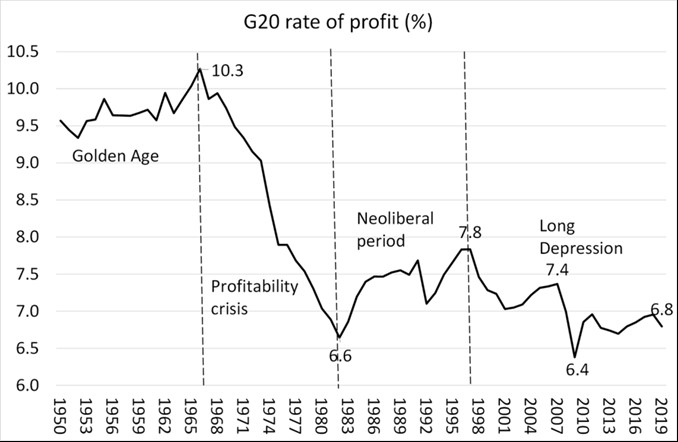

Declining growth rates have gone hand in hand with, or rather been caused by, a corresponding decline in the profit rate, which is, ultimately, the result of the declining share of living labour and rising share of dead labour (machines and raw materials) in total capital. Marx once noted, “this law, and it is the most important law of political economy, is that the rate of profit has a tendency to fall with the progress of capitalist production.”32

Figure 2 shows the development of the profit rate in the 20 largest economies (G20 states) in the past seven decades. As we can see, there has been a long-term tendency of the profit rate to fall, as Marx predicted.

Figure 2: Rate of Profit in G20 Economies 1950-201933

World capitalism has not restored its growth rates of earlier times — despite numerous political interventions by the ruling class and despite “antagonistic cooperation”. It remains trapped in a long-time period of stagnation and decline.

Overestimating the rise of Chinese and Russian imperialism?

Li believes that I and others “overly downplay the decline of US hegemony while overestimating the rise of new imperialists as a counterbalance to US imperialism”. Unfortunately, he does not provide a single quote to prove his claim. I have not the slightest idea why Li thinks that I underestimate the decline of US hegemony. In any case, I think his criticism is not justified.

I have, however, shown how China’s capitalist class has not only massively enriched itself at the cost of the domestic working class but also been able to challenge the US on the world market. Again, I will limit myself to demonstrating this with just a few figures and refer interested readers to more elaborate studies.34

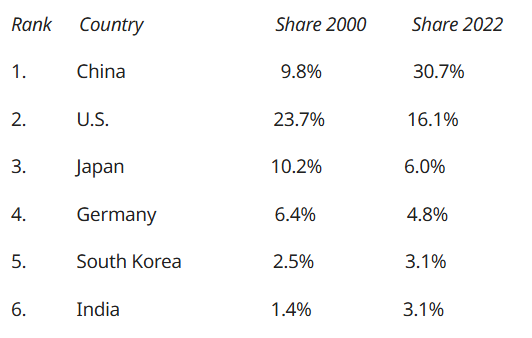

In the tables below, you can see that China has rapidly caught up with the long-time hegemon, US imperialism. Table 2 shows that China’s share in global manufacturing output was less than half of the US in the year 2000 (9.8% to 23.7%); however, by 2022, its share was already nearly double that of its Western rival (30.7% to 16.1%).

Table 2. Top Six Countries in Global Manufacturing, 2000 and 202235

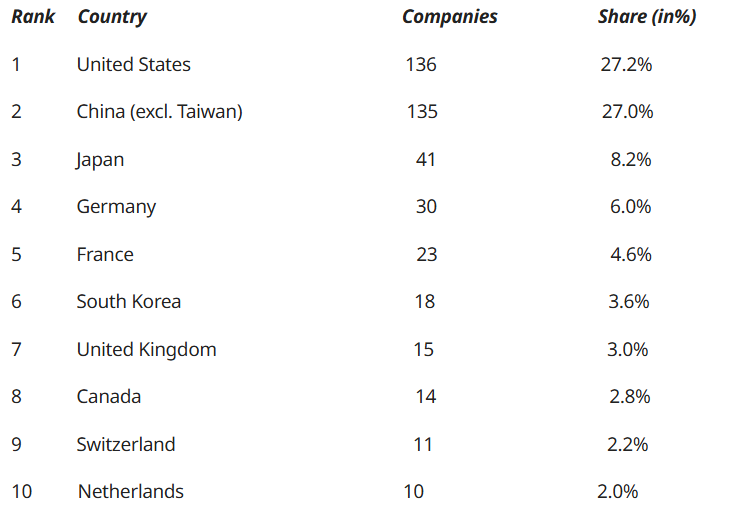

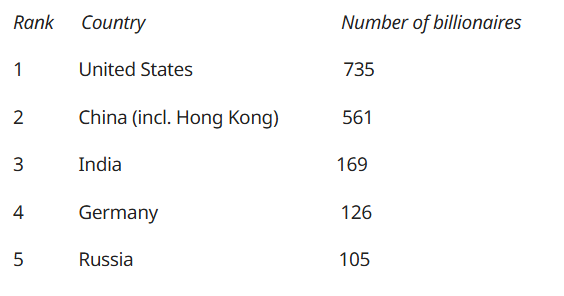

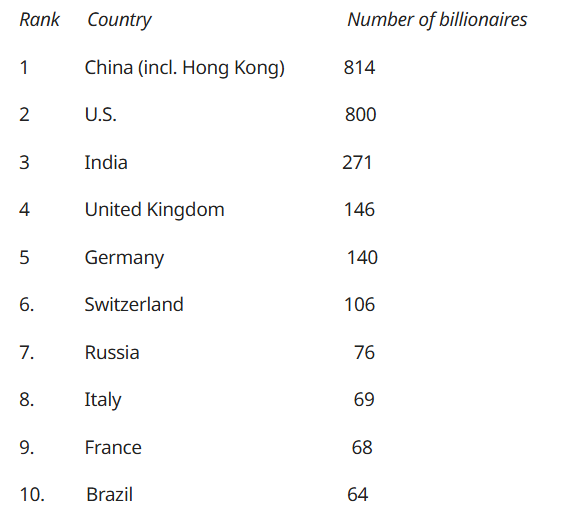

A similar picture emerges when we look at the national composition of the world’s leading corporations as well as the global ranking of billionaires (Table 3-5). In all these categories, China has become No.1 or 2 — ahead or behind the US

Table 3. Top 10 Countries with the Ranking of Fortune Global 500 Companies (2023)36

Table 4. Top 5 Countries of the Forbes Billionaires 2023 List37

Table 5. Top 10 Countries of the Hurun Global Rich List 202438

Russia has also developed a monopoly capital that dominates the domestic market and exports capital to various other countries, mainly in Central Asia and Eastern Europe. Its economic strength has been demonstrated by the fact that it has managed to resist an unprecedented wave of sanctions by Western powers for nearly three years. Its position on the world market is substantially weaker, albeit it has recently surpassed Germany’s and Japan’s GDP in PPP terms (Purchase Power Parity).39

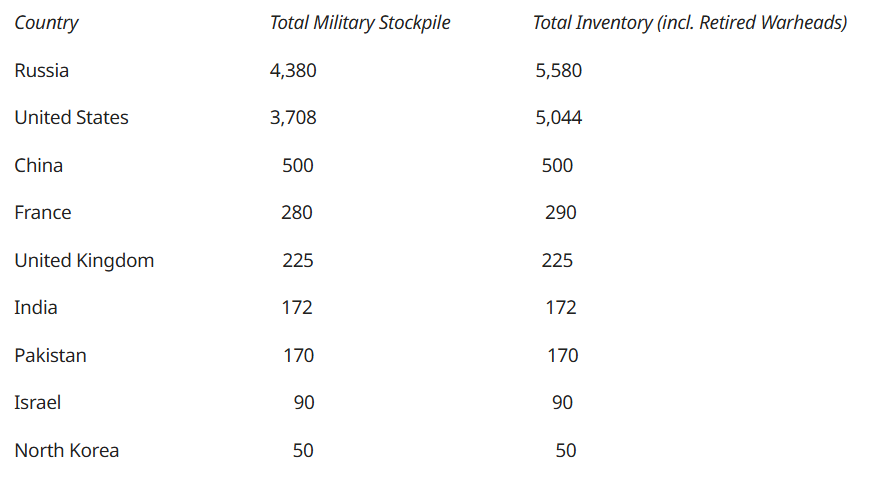

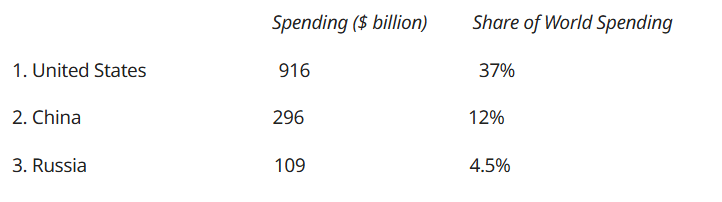

But while in economic terms Russia is clearly behind the US and China, it is a leading force in the military field. It has the largest nuclear arsenal and the third highest military expenditure. (See Table 6 and 7) Furthermore, it has demonstrated its military aggressiveness through numerous military interventions in other countries to expand its influence, putting down popular rebellions or keeping allied dictatorships in power (for example in Chechnya, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Syria, Libya, Mali, etc.)40

Table 6. World Nuclear Forces, 202441

Table 7. Military Expenditure, in Billion US-Dollar as Share of World Spending, 202342

Furthermore, China and Russia have substantially expanded their spheres of influence as the enlargement of BRICS shows. Four states — Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and United Arab Emirates — formally joined the five original BRICS members (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) at the start of 2024. One country, Saudi Arabia, has been invited to join but still not decided if it will. In October 2024, 13 other states became so-called “partner countries” (Algeria, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Türkiye, Uganda, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam).

As I elaborate in more detail in my reply to Katz, BRICS+ had, after its expansion to nine member states in 2023, a combined population of about 3.5 billion, or 45% of the world’s people (it is now more than half if one includes the new “partner countries”). Its combined GDP, depending on the method of calculation, is either a bit more than one third behind the Western Great Powers (G7) or has already surpassed the old imperialist powers. Likewise, BRICS+ accounts for 38.3% of the total world industrial production — the main sector of capitalist value production.

As for energy sources, BRICS+ members own 47% of the world’s oil reserves and 50% of its natural gas reserves.43 As of 2024, BRICS+ controls approximately 72% of the world's rare earth metal reserves.44

It is true that BRICS+ is not a homogenous and centralised alliance. Still, it is a “a non-western group", as Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russian president Vladimir Putin emphasised, dominated by Chinese and Russian imperialism. Furthermore, BRICS+ countries are capitalistically less developed and have a lower living standard.

Nevertheless, while Li thinks that I overestimate the rise of China and Russia as new imperialist powers, I believe he underestimates this process and, as a result, also underestimates the acceleration of inter-imperialist rivalry. The military threats and nuclear sabre rattling between NATO and Russia, as well as the accelerating military tensions between Washington and Beijing in the South China Sea around Taiwan, are clear indications that the imperialist system is not so much characterised by “antagonistic cooperation” but rather by antagonistic contradictions.

It is therefore hardly surprising that, as SIPRI reports, global military expenditure has risen year on year since the mid-’90s and at $2,443 billion is about twice as high as it was 30 years ago. 45

The accelerating inter-imperialist rivalry is not limited to armament and military tensions. There is also an escalating trade war between the US, China, EU and Russia combined with rising protectionism. In fact, globalisation has ended since the Great Recession in 2008. Since then, world merchandise trade has declined as a share of global output from 51.2% (2008) to 45.8% (2023).46

So, when Li says that “far from undoing the neoliberal world order, the capitalist class innovates new terms for maintaining and reforming globalization”, he completely misunderstands the direction of development of relations between imperialist powers.

For all these reasons, it is difficult to understand why Li objects to the category of a “new Cold War” between the Western and Eastern powers, calling it an “ideological fiction”. Does he not see the rising militarism and acceleration of rivalry, which all point to another world war between the imperialist powers?

As I insisted before, Marxists must “determine the general direction of development” to understand the coming ruptures and explosions. Li’s concept of imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation” does not help in understanding the dynamics of the current world situation.

Is capitalist interdependence an obstacle for inter-imperialist war?

Finally, I want to deal with another important argument Li raises in his essay. He argues that “economic interdependence” has been a key feature of modern imperialism and, as a result, this constitutes the material basis for “antagonistic cooperation” between powers. Li even believes that such economic interdependence makes inter-imperialist war impossible or at least unlikely:

Indeed, global economic integration still existed in salient forms during the First World War, but mostly just contained within geopolitical camps, which historian Jamie Martin calls “strained interdependence.” However, the rise of neoliberalism has developed a level of interdependence that endures even across rival state blocs, thus undercutting the possibility of open interimperialist warfare witnessed in the first two World Wars.

This is wrong — both methodologically and historically. Bukharin correctly pointed out that interdependence not only deepens economic links but also accelerates rivalry. In the past years, China and the US have been among each other’s most important trading partners. This has not prevented these powers from starting and accelerating a trade war. The same is now the case between China and the EU, where the latter has imposed substantial tariffs on Chinese imports. True, big business on both sides is not happy about this. But in the end, they have to subordinate themselves to the objective laws of capitalism and its inherent inter-imperialist rivalry.

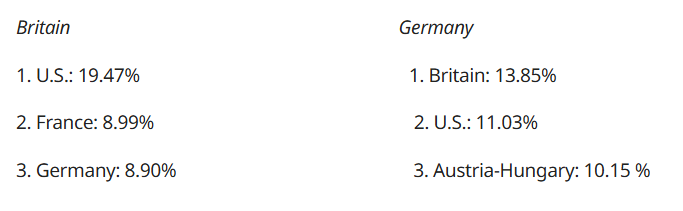

There is a historic precedent for such a development. Britain and Germany, two major rivals in World War I, had close economic relations before 1914.47 Table 8 shows that Britain was Germany’s most important trade partner before 1914 (the US was No. 2) while Germany was nearly as important as France for Britain’s trade. However, such economic interdependence did not prevent these powers from launching the most devastating war against each other.

Table 8. Main Trade Partners of Britain and Germany, 1890-1913 (Average % Share)48

In the long run, increasing economic interdependence between imperialist powers does not result in a more stable capitalist world system. Nor does it create a type of imperialism characterised by “antagonistic cooperation”. Rather, imperialism remains a system full of antagonistic contradictions.

Conclusions

1. The concept of imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation” does not allow us to understand the dynamics of the current world situation. Li correctly recognises the imperialist nature of the old Western and new Eastern powers (China and Russia), but he mistakenly criticises supporters of the orthodox theory of imperialism of overestimating the rivalry between these.

2. Referencing Thalheimer and Bukharin as pioneers of the concept of imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation” is misleading. Bukharin, despite his weaknesses, emphasised rivalry and antagonism between imperialist powers, which inevitably had to result in wars. It is true that Thalheimer elaborated the thesis of “antagonistic cooperation” between imperialist powers in 1946. But this was a (correct) description of a specific global situation characterised by the huge expansion of the Stalinist states and the outcome of World War II, with the US as the absolute hegemon among imperialist states. His thesis of more cooperation between imperialist powers was directly related to their collective aggressive approach against the Stalinist states, which pointed to a new world war. Thalheimer considered that inter-imperialist tensions would be reduced because they were overridden by the huge acceleration of tensions between imperialist and degenerated worker states. However, after Stalinism collapsed in 1989-91, Thalheimer’s concept is no longer applicable for imperialism today.

3. It is true that Bukharin, the political mentor of Thalheimer, was influenced by the philosophy of Bogdanov, a staunch opponent of dialectical materialism. He advocated a world view that incorporated the mechanist equilibrium theory: a concept that downplays the role of internal contradictions as the driving force of motion. Consequently, supporters of such a method consider equilibrium as the main feature of matter when, in fact, it is motion. The Bukharinite method underestimates the tendencies of rupture, crisis and explosions in the world situation and overestimates its stability and equilibrium. Imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation“ suffers from such methodological deficits.

4. From the point of view of materialist dialectic, the driving force of motion are the internal contradictions caused by the unity and struggle of opposites. The mechanist method is incapable of answering this question correctly: what is the determining characteristic of matter — a state of equilibrium or contradiction and motion as a result of the struggle of opposites? From the point of view of materialist dialectic, the correct answer is that the struggle of opposites and contradiction is the determining feature, since it causes motion, transformation, progress. In contrast, the state of equilibrium is only a temporary moment.

5. There is a clear connection between the mechanist equilibrium theory of Bukharin and imperialism as “antagonistic cooperation”. The philosophy of downplaying the struggle of opposites and internal contradictions causing motion results in an understanding of reality as a state of (moving) equilibrium. On such a methodological basis, one ends up viewing the world situation as primarily characterised by relative stability and cooperation between imperialists. As a result, one can not recognise the direction of motion of world politics and economy.

6. Consequently, Li does not take sufficient account of the crisis-ridden character and decay of the imperialist world system, both economically and politically. The capitalist world economy is trapped in long-term stagnation and decline, climate change is threatening the survival of humanity, and social misery and wars are spreading.

7. Li’s criticism that I overestimate the rise of Chinese and Russian imperialism ignores the qualitative changes in the relation of forces between the Great Powers in the past 10-20 years. The Eastern imperialists are seriously challenging Western hegemony — economically, political and militarily. In fact, Li’s critique is related to his underestimation of inter-imperialist rivalry and his view that “antagonistic cooperation” is the main feature of the world situation.

8. Li claims that “economic interdependence” is a key feature of modern capitalism and that this “undercut[s] the possibility of open interimperialist warfare”. However, history has shown that this is not true. In the long run, increasing economic interdependence between imperialist powers does not result in a more stable capitalist world system. It does not create a type of imperialism characterised by “antagonistic cooperation”. Rather, imperialism remains a system full of antagonistic contradictions.

Michael Pröbsting is a socialist activist and writer. He is the editor of the website http://www.thecommunists.net/, where a version of this article first appeared.

- 1

Michael Pröbsting: Age of ‘Empire’ or age of imperialism? A reply to Claudio Katz https://links.org.au/age-empire-or-age-imperialism-reply-claudio-katz

- 2

Promise Li: Imperialism as Antagonistic Cooperation, https://links.org.au/imperialism-antagonistic-cooperation. All quotes are from this essay if not indicated otherwise.

- 3

See Anti-Imperialism in the Age of Great Power Rivalry. The Factors behind the Accelerating Rivalry between the U.S., China, Russia, EU and Japan. A Critique of the Left’s Analysis and an Outline of the Marxist Perspective, RCIT Books, Vienna 2019, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/anti-imperialism-in-the-age-of-great-power-rivalry/; The Great Robbery of the South. Continuity and Changes in the Super-Exploitation of the Semi-Colonial World by Monopoly Capital Consequences for the Marxist Theory of Imperialism, RCIT Books, 2013, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/great-robbery-of-the-south/

- 4

Promise Li: US-China rivalry, ‘antagonistic cooperation’ and anti-imperialism in the 21st century, 14 September, 2023, https://links.org.au/us-china-rivalry-antagonistic-cooperation-and-anti-imperialism-21st-century

- 5

For a critique of the “sub-imperialism” theory see Semi-Colonial Intermediate Powers and the Theory of Sub-Imperialism. A contribution to an ongoing debate amongst Marxists and a proposal to tackle a theoretical problem, 1 August 2019, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/semi-colonial-intermediate-powers-and-the-theory-of-sub-imperialism/; see also chapter IV (“The Marxist Criteria for an Imperialist Great Power“ in our above-mentioned book “Anti-Imperialism in the Age of Great Power Rivalry”)

- 6

Useful biographies of Bukharin are e.g. Stephen Cohen: Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution. A Political Biography, 1888–1938. Oxford University Press, 1980; Wladislaw Hedeler: Nikolai Bucharin. Stalins tragischer Opponent. Eine politische Biographie. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2015; Adolf G. Löwy: Die Weltgeschichte ist das Weltgericht. Leben und Werk Nikolai Bucharins. Promedia-Verlags-Gesellschaft, Wien 1990; Anna Larina: This I cannot forget. The Memoirs of Nikolai Bukharin's Widow. W. W. Norton & Co, New York 1993.

- 7

On the history of the Right Opposition in English-language see Robert J. Alexander: The Right Opposition. The Lovestoneites and the International Communist Opposition of the 1930s, Greenwood Press, London 1981

- 8

August Thalheimer: Grundlinien und Grundbegriffe der Weltpolitik nach dem 2. Weltkrieg, Gruppe Arbeiterpolitik, 1946, p. 11 and 9 (our translation)

- 9

Nikolai Bukharin: Imperialism and World Economy (1915), International Publishers, New York 1929, p. 104

- 10

Nikolai Bukharin: The Politics and Economics of the Transition Period (1920), Routledge, Abingdon 2003, pp. 63-64

- 11

Nikolai Bukharin: Imperialism and World Economy, p. 148

- 12

Ibid., p. 54

- 13

On Alexander Bogdanov see James D. White: Red Hamlet: The Life and Ideas of Alexander Bogdanov, Brill, Leiden 2018; Dietrich Grille: Lenins Rivale: Bogdanov und seine Philosophie, Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Cologne 1966; see also the foreword of Bogdanov's Tektology Vol. 1 by Vadim N. Sadovsky and Vladimir V. Kelle, Centre for Systems Studies, University of Hull, 1996, pp. iii-xxii; V.A. Bazarov: Bogdanov as a Thinker, in: Alexander Bogdanov: Empiriomonism. Essays in Philosophy, Books 1–3, Brill, Leiden 2020, pp. xvii-xli.

- 14

Nikolai Bukharin: Historical Materialism. A System of Sociology (1921), Authorized Translation from the third Russian edition, George Allen & Unwin, Ltd, London 1926, p. 74

- 15

V.I. Lenin: On the Question of Dialectics (1915); in: CW 38, p.358

- 16

Nikolai Bukharin: Historical Materialism, p. 79

- 17

Ibid., p. 74

- 18

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Science of Logic, George Allen & Unwin, Ltd, New York 1969, p. 439 (also quoted in V.I. Lenin: Conspectus of Hegel’s Book the Science of Logic (1914); in: LCW 38, pp. 178-179)

- 19

Friedrich Engels: Anti-Dühring. Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science, in: MECW Vol. 25, pp. 55-56

- 20

V.I. Lenin: On the Question of Dialectics (1915); in: LCW 38, p.358

- 21

Friedrich Engels: Dialectics of Nature, in: MECW Vol. 25, pp. 525-526

- 22

Abram Deborin: Lenin als revolutionärer Dialektiker (1925); in: Nikolai Bucharin, Abram Deborin: Kontroversen über dialektischen und mechanistischen Materialismus, Frankfurt a.M. 1974, p. 54 (our translation)

- 23

N.A. Karew: Die Theorie des Gleichgewichts und der Marxismus; in: Wilhelm Goerdt (Hrsg.): Die Sowjetphilosophie. Wendigkeit und Bestimmtheit. Dokumente, Darmstadt 1967, p. 139 (our translation)

- 24

Ibid., pp. 140-141

- 25

Abram Deborin: Lenin als revolutionärer Dialektiker (1925); in: Unter dem Banner des Marxismus, 1. Jahrgang (1925-26), p. 224 (our translation)

- 26

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Science of Logic, (Translated by A.V. Miller), Humanity Books, New York 1969, p. 826

- 27

Leon Trotsky: The capitalist curve of development (1923), in: Leon Trotsky: Problems of Everyday Life, New York, 1994, pp. 273-280

- 28

For our analysis of the current historic period see e.g. chapter 14 in the above-mentioned book “The Great Robbery of the South” as well as chapter I and II in the above-mentioned book “Anti-Imperialism in the Age of Great Power Rivalry”.

- 29

See RCIT: Theses on Agriculture and Ecology, September 2023, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/theses-on-agriculture-and-ecology/, Almedina Gunić: The Deadly Breath of Imperialism, 23.10.2017, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/pollution-caused-the-death-of-9-million-people-in-2015/

- 30

Murray E.G. Smith, Josh Watterton: Valorization, Financialization & Crisis: A Temporal Value-Theoretic Approach, 2021, p. 5

- 31

M. Ayhan Kose, Franziska Ohnsorge (Eds.): A Decade since the Global Recession, Lessons and Challenges for Emerging and Developing Economies, World Bank, 2019, p. 9

- 32

Karl Marx: Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63. Capital and Profit. 7) General Law of the Fall in the Rate of Profit with the Progress of Capitalist Production; in: MECW, Volume 33, pp. 104-145; http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1861/economic/ch57.htm

- 33

Michael Roberts: Has globalisation ended? (2022), https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2022/04/27/has-globalisation-ended/

- 34

I have published a number of works about capitalism in China and its rise to an imperialist power. The most important ones are the following: Chinese Imperialism and the World Economy, an essay published in the second edition of “The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism” (edited by Immanuel Ness and Zak Cope), Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020, https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-319-91206-6_179-1; China: On the Relationship between the “Communist” Party and the Capitalists. Notes on the specific class character of China’s ruling bureaucracy and its transformation in the past decades, 8 September 2024, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/china-on-the-relationship-between-communist-party-and-capitalists/; China: On Stalinism, Capitalist Restoration and the Marxist State Theory. Notes on the transformation of social property relations under one and the same party regime, 15 September 2024, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/china-on-stalinism-capitalist-restoration-and-marxist-state-theory/; China: An Imperialist Power … Or Not Yet? A Theoretical Question with Very Practical Consequences! Continuing the Debate with Esteban Mercatante and the PTS/FT on China’s class character and consequences for the revolutionary strategy, 22 January 2022, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/china-imperialist-power-or-not-yet/; China‘s transformation into an imperialist power. A study of the economic, political and military aspects of China as a Great Power (2012), in: Revolutionary Communism No. 4, https://www.thecommunists.net/publications/revcom-1-10/#anker_4; How is it possible that some Marxists still Doubt that China has Become Capitalist? An analysis of the capitalist character of China’s State-Owned Enterprises and its political consequences, 18 September 2020, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/pts-ft-and-chinese-imperialism-2/; Unable to See the Wood for the Trees. Eclectic empiricism and the failure of the PTS/FT to recognize the imperialist character of China, 13 August 2020, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/pts-ft-and-chinese-imperialism/; China’s Emergence as an Imperialist Power (Article in the US journal 'New Politics'), in: “New Politics”, Summer 2014 (Vol:XV-1, Whole #: 57). See many more RCIT documents at a special sub-page on the RCIT’s website: https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/china-russia-as-imperialist-powers/.

- 35

Figures for the year 2000: APEC: Regional Trends Analysis, May 2021, p. 2; the figures for Germany and India in the first column are for the year 2005 (UNIDO: Industrial Development Report 2011, p. 194); figures for the year 2022: UNIDO: International Yearbook of Industrial Statistics Edition 2023, pp. 36-37

- 36

Fortune Global 500, August 2023, https://fortune.com/ranking/global500/2023/ (the figures for the share is our calculation)

- 37

Forbes: Forbes Billionaires 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/chasewithorn/2023/04/04/forbes-37th-annual-worlds-billionaires-list-facts-and-figures-2023/?sh=23927e7477d7

- 38

Hurun Global Rich List 2024, 26.03.2024, https://www.hurun.net/en-US/Info/Detail?num=K851WM942LBU

- 39

See Michael Pröbsting: Russia Overtakes Japan to Become Fourth Largest Economy in the World, 5 July 2024, https://www.thecommunists.net/worldwide/global/russia-overtakes-japan-to-become-fourth-largest-economy-in-the-world/

- 40

I have published a number of works about capitalism in Russia and its rise to an imperialist power. The most important ones are the following pamphlets: The Peculiar Features of Russian Imperialism. A Study of Russia’s Monopolies, Capital Export and Super-Exploitation in the Light of Marxist Theory, 10 August 2021, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/the-peculiar-features-of-russian-imperialism/; Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism and the Rise of Russia as a Great Power. On the Understanding and Misunderstanding of Today’s Inter-Imperialist Rivalry in the Light of Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism. Another Reply to Our Critics Who Deny Russia’s Imperialist Character, August 2014, http://www.thecommunists.net/theory/imperialism-theory-and-russia/; Russia as a Great Imperialist Power. The formation of Russian Monopoly Capital and its Empire, 18 March 2014, http://www.thecommunists.net/theory/imperialist-russia/.

- 41

SIPRI Yearbook 2024: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security, p. 272

- 42

Nan Tian, Diego Lopes Da Silva, Xiao Liang and Lorenzo Scarazzato: Trends in World Military Expenditure, SIPRI, 2023, p. 2

- 43

See on this: Henry Meyer, S'thembile Cele, and Simone Iglesias: Putin Hosts BRICS Leaders, Showing He Is Far From Isolated, Bloomberg, 22 October 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-10-22/putin-hosts-brics-leaders-in-russia-defying-attempts-from-west-to-isolate-him; Dr Kalim Siddiqui: The BRICS Expansion and the End of Western Economic and Geopolitical Dominance, 30 October 2024, https://worldfinancialreview.com/the-brics-expansion-and-the-end-of-western-economic-and-geopolitical-dominance/; Walid Abuhelal: Can the Brics end US hegemony in the Middle East? Middle East Eye, 22 October 2024 https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/can-brics-end-us-hegemony-middle-east; Anthoni van Nieuwkerk: BRICS+ wants new world order sans shared values or identity, 30 October 2024 https://asiatimes.com/2024/10/brics-wants-new-world-order-sans-shared-values-or-identity/

- 44

Ben Aris: Can the BRICS beat the G7? Intellinews, 19 October 2024, https://www.intellinews.com/can-the-brics-beat-the-g7-348632/?source=south-africa

- 45

Nan Tian et al: Trends in World Military Expenditure, p. 2

- 46

World Bank: Merchandise trade (% of GDP), accessed on 21 November 2024, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TG.VAL.TOTL.GD.ZS?view=chart

- 47

See on this Helga Nussbaum: Der europäische Wirtschaftsraum. Verflechtung, Angleichung, Diskrepanz, in: Fritz Klein, Karl Otmar von Aretin (Eds): Europea um 1900, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1989, p. 49

- 48

Stefano Battilossi: The Determinants of Multinational Banking during the First Globalization, 1870-1914, Working Papers 114, Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Austrian Central Bank), 2006, p. 40