Researchers keep a mammalian cochlea alive outside the body for the first time

image:

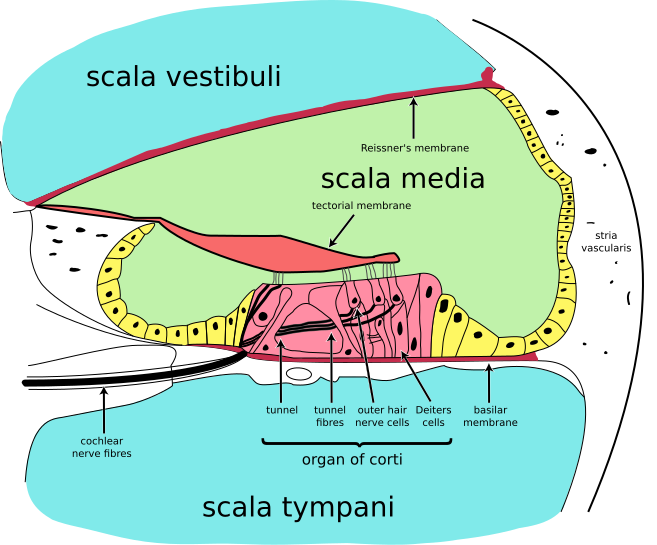

A specially designed chamber that helps imitate the living environment of the cochlea.

view moreCredit: Chris Taggart/The Rockefeller University

Shortly before his death in August 2025, A. James Hudspeth and his team in the Laboratory of Sensory Neuroscience at The Rockefeller University achieved a groundbreaking technological advancement: the ability to keep a tiny sliver of the cochlea alive and functional outside of the body for the first time. Their new device allowed them to capture the live biomechanics of the cochlea’s remarkable auditory powers, including exceptional sensitivity, sharp frequency tuning, and the ability to encode a broad range of sound intensities.

“We can now observe the first steps of the hearing process in a controlled way that was previously impossible,” says co-first author Francesco Gianoli, a postdoctoral fellow in the Hudspeth lab.

Described in two recent papers (in PNAS and Hearing Research, respectively), the innovation is a product of Hudspeth’s five decades of work illuminating the molecular and neural mechanisms of hearing—insights that have illuminated new paths to preventing or reversing hearing loss.

With this advance, the researchers have also provided direct evidence of a unifying biophysical principle that governs hearing across the animal kingdom, a subject Hudspeth investigated for more than a quarter-century.

“This study is a masterpiece,” says biophysicist Marcelo Magnasco, head of the Laboratory of Integrative Neuroscience at Rockefeller, who collaborated with Hudspeth on some of his seminal findings. “In the field of biophysics, it’s one of the most impressive experiments of the last five years.”

The mechanics of hearing

Though the cochlea is a marvel of evolutionary engineering, some of its fundamental mechanisms have long remained hidden. The organ’s fragility and inaccessibility—embedded as it is in the densest bone in the body—have made it difficult to study in action.

These challenges have long frustrated hearing researchers, because most hearing loss results from damage to sensory receptors called hair cells that line the cochlea. The organ has some 16,000 of these hair cells, so-called because each one is topped by a few hundred fine “feelers,” or stereocilia, that early microscopists likened to hair. Each bundle is a tuned machine that amplifies and converts sound vibrations into electrical responses that the brain can then interpret.

It’s well documented that in insects and non-vertebrate animals—such as the bullfrogs studied in Hudspeth’s lab—a biophysical phenomenon known as a Hopf bifurcation is key to the hearing process. The Hopf bifurcation describes a kind of mechanical instability, a tipping point between complete stillness and oscillations. At this knife-edge, even the faintest sound tips the system into movement, allowing it to amplify weak signals far beyond what would otherwise register.

In the case of bullfrog cochlea, the instability is in the bundles of the sensory hair cells, which are always primed to detect incoming sound waves. When those waves hit, the hair cells move, amplifying the sound in what’s called the active process.

In collaboration with Magnasco, Hudspeth documented the existence of the Hopf bifurcation in the bullfrog cochlea in 1998. Whether it exists in the mammalian cochlea has been a subject of debate in the field ever since.

To answer that question, Hudspeth’s team decided they needed to observe the active process in a mammalian cochlea in real time and at a greater level of detail than ever before.

A sliver of a spiral

To do so, the researchers turned to the cochlea of gerbils, whose hearing falls in a similar range as humans. They excised slivers no larger than .5 mm from the sensory organ, in the region of the cochlea that picks up the middle range of frequencies. They timed their excision to a developmental moment in which the gerbil’s hearing is mature but the cochlea hasn’t fully fused to the highly dense temporal bone.

They placed a sliver of tissue within a chamber designed to reproduce the living environment of the sensory tissue, including continuously bathing it in nutrient-rich liquids called endolymph and perilymph and maintaining its native temperature and voltage. Key to the development of this custom device were Brian Fabella, a research specialist in the Hudspeth lab, and instrumentation engineer Nicholas Belenko, from Rockefeller’s Gruss Lipper Precision Instrumentation Technologies Resource Center.

They then began to play sounds via a tiny speaker and observed the response.

Discovering a biophysical principle

Among the processes they witnessed were how the opening and closing of ion channels in the hair bundles add energy to the sound-driven vibrations, amplifying them, and how outer hair cells elongate and contract in response to voltage changes through a process called electromotility.

“We could see in fine detail what every piece of the tissue is doing at the subcellular level,” Gianoli says.

“This experiment required an extraordinarily high level of precision and delicacy,” notes Magnasco. “There’s both mechanical fragility and electrochemical vulnerability at stake.”

Importantly, they observed that key to the active process was indeed a Hopf bifurcation—the tipping point that turned mechanical instability into sound amplification. “This shows that the mechanics of hearing in mammals is remarkably similar to what has been seen across the biosphere,” says co-first author Rodrigo Alonso, a research associate in the lab.

A device that could lead to future treatments

The scientists anticipate that experimentation using the ex vivo cochlea will improve their understanding of hearing and hopefully point to better therapies.

“For example, we will now be able to pharmacologically perturb the system in a very targeted way that has never been possible before, such as by focusing on specific cells or cell interactions,” says Alonso.

There’s a great need in the field for new potential therapies. “So far, no drug has been approved to restore hearing in sensorineural loss, and one reason for that is that we still have an incomplete mechanistic understanding of the active process of hearing,” Gianoli says. “But now we have a tool that we can use to understand how the system works, and how and when it breaks—and hopefully think of ways to intervene before it’s too late.”

Hudspeth found the results deeply gratifying, Magnasco adds. “Jim had been working on this for more than 20 years, and it’s a crowning achievement for a remarkable career.”

Journal

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Article Title

Amplification through local critical behavior in the mammalian cochlea

Posterior canal Superior canal Utricle Horizontalcanal Vestibule Cochlea SacculeParts of the inner ear, showing the cochlea Posterior canal Superior canal Utricle Horizontalcanal Vestibule Cochlea SacculeParts of the inner ear, showing the cochlea | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒkliə, ˈkoʊkliə/ |

| Part of | Inner ear |