Monica Duffy Toft and Sidita Kushi’s 2023 book Dying by the Sword is both a work of scholarship and an unflinching indictment. It demolishes the enduring myth of the United States as a hesitant warrior, reluctantly drawn into conflicts by others. Instead, using their Military Intervention Project – the most comprehensive dataset of its kind – they prove that America has been the most interventionist state in modern history. The numbers are stark. From 1776 to 2019 the United States engaged in 392 military interventions. Thirty-four percent of these occurred in Latin America and the Caribbean, twenty-three percent in East Asia and the Pacific, fourteen percent in the Middle East and North Africa, thirteen percent in Europe and Central Asia, and nine percent in sub-Saharan Africa. More than half of all interventions have taken place since 1945, and nearly one-third since the end of the Cold War. Remarkably, Toft and Kushi note that 1974 was the last year in which the United States did not launch at least one new military intervention. Before that, the only other pause in the postwar era was 1952 – underscoring how constant war has become the American default. Measured over time, the tempo of U.S. intervention has accelerated dramatically. Between 1776 and 1945, Washington intervened roughly once to one and a half times per year. During the Cold War this climbed to nearly 2.5 interventions annually. After the Cold War it surged to 4.6 per year, and since 2001 it has remained extraordinarily high at 3.6 annually.

Perhaps the book’s most damning finding comes from their comparison of U.S. hostility levels with those of its enemies. During the Cold War, the hostility levels were roughly symmetrical. But in every period before and after, the United States displayed higher hostility levels than its adversaries – often significantly higher. This strongly suggests that most U.S. wars throughout its history were not defensive wars, but imperial wars of choice in which Washington was the prime escalator. Moreover, from 1776 until the end of the Cold War more than 75 percent of all US interventions were unilateral. Since 1990 this percentage dropped to 57.7 percent. The self-declared global policeman never cared very much for global opinion or international law.

One of Toft and Kushi’s most revealing statistical facts is that America’s principal adversaries today are not random enemies, but rather the very countries it has intervened in most often throughout its history. The top seven are telling: China, Russia, Mexico, North Korea, Cuba, Iran, and Nicaragua. Far from building stability, repeated interventions left behind legacies of grievance, mistrust, and resistance. What emerges is a sobering picture: today’s conflicts are not accidents of geopolitics but the direct outgrowth of a long history in which Washington sought to impose its will by force. In other words, America’s most enduring enemies are, to a large extent, the ones it helped create. And crucially, U.S. military interventions, interference, economic sanctions, and constant threats in these countries not only entrenched cycles of hostility but almost certainly contributed to their lack of democracy, liberalism, and prosperity – the authoritarian regimes that Washington now loves to demonize are, in no small part, the product of its own aggressions. When people live under siege from a great power, when their societies are scarred by violence, poverty, and the erosion of education and opportunity, they do not become more democratic or liberal. Instead, fear, hardship, and insecurity create fertile ground for authoritarian rule – and Washington’s aggressions have repeatedly helped bring exactly that about. In the starkest terms, America manufactures its own enemies, and then condemns them for the very conditions it helped to create.

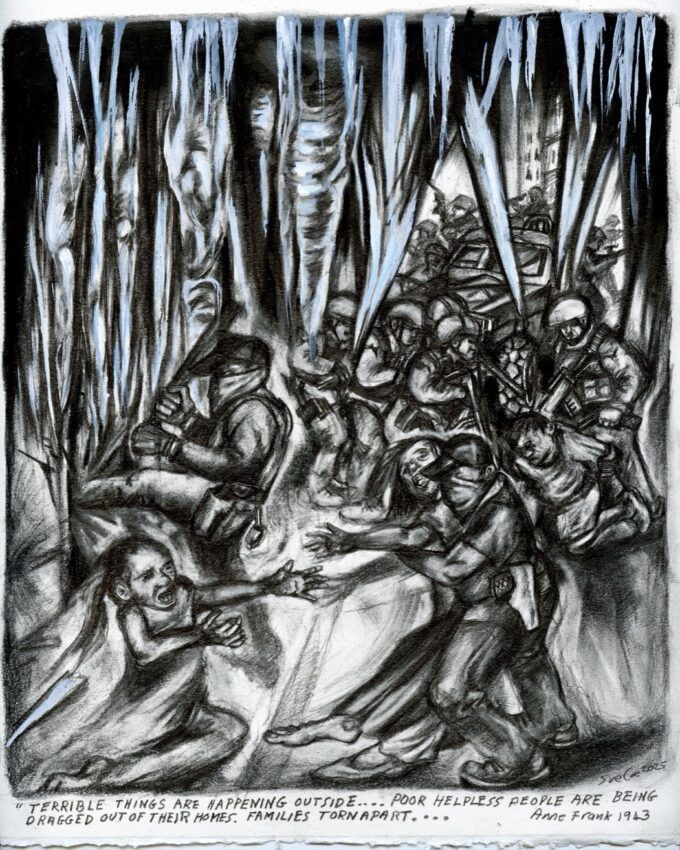

This review draws on both the book and its companion case studies to provide a chronological overview of the crimes that resulted from this pattern of intervention. From the scorched-earth campaigns against Indigenous peoples to the water-cure torture in the Philippines, from the terror bombings of Japan, Germany and Korea to the support for death squads in Guatemala and El Salvador, from the chemical devastation of Vietnam to the War on Terror, Toft and Kushi’s evidence adds up to a damning portrait. America’s wars have rarely been wars of survival. They have overwhelmingly been wars of choice, driven by expansionist, commercial, and imperial ambitions.

Empire at Home: Conquest and Expansion

The first century of American military activity was devoted above all to continental conquest. The wars against Indigenous nations were systematic campaigns of annihilation and displacement, not isolated frontier skirmishes. Entire villages were burned to the ground, crops destroyed, and populations forced onto death marches like the Trail of Tears. From the Seminoles in Florida to the Sioux and Apache on the Plains and in the Southwest, the pattern was the same: the use of overwhelming force to clear land for settlers, often accompanied by massacres of noncombatants.

At the same time, the young republic projected force overseas. In North Africa, the Barbary Wars saw U.S. naval bombardments of Tripoli and Algiers, coupled with punitive raids on coastal towns. In the Caribbean, American warships landed marines in places like Cuba and Puerto Rico long before they became formal U.S. possessions. In the Pacific, early interventions targeted Polynesian islands and Chinese ports in the name of commerce, often leaving destruction behind.

The Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 was the republic’s first major overseas conquest. Framed as defense, it was in reality an expansionist war that stripped Mexico of half its territory. U.S. troops occupied cities, committed looting, and carried out summary executions of suspected guerrillas. Civilians bore the brunt of the violence, and the conquered lands became the foundation of America’s continental empire.

By mid-century the pattern was unmistakable: the United States was not a besieged power fighting for survival. It was an expansionist republic using force to displace, conquer, and secure commercial advantage.

The Imperial Turn: From the Caribbean to the Pacific

By the end of the nineteenth century the United States had outgrown its continental frontier and turned outward. The Spanish-American War marked the opening of a new imperial phase. Cuba was occupied, Puerto Rico and Guam annexed, and the Philippines violently subdued. In the Philippines the U.S. military unleashed a counterinsurgency so brutal it stands comparison with the worst colonial wars of Europe. Villages were burned to the ground, civilians herded into concentration zones, and torture became routine. The “water cure,” a form of simulated drowning, was applied systematically. On the island of Samar, General Jacob Smith ordered his troops to turn the region into a “howling wilderness” and to kill any male over ten years old. Tens of thousands of Filipinos died in a war of pacification waged under the banner of civilization.

The new century saw the Marines become the iron fist of American empire in the Caribbean and Central America. Nicaragua was invaded repeatedly, sometimes for years at a stretch, and its politics subordinated to Washington’s will. Honduras endured a series of occupations and landings designed to protect American corporate interests. Haiti was occupied from 1915 to 1934, during which time U.S. forces imposed forced labor, shot down protestors, and maintained direct military rule. In the Dominican Republic, another occupation beginning in 1916 installed a regime sustained by American bayonets and riddled with abuses against civilians. In Cuba, formal independence masked a reality of repeated American interventions, military occupations, and economic domination.

The methods were strikingly consistent: forced labor in Haiti, executions and collective punishments in the Dominican Republic, massacres of insurgents in Nicaragua, and the training of local security forces whose brutality was legendary. Across the Caribbean basin, U.S. interventions propped up regimes, safeguarded corporate plantations and banks, and crushed dissent through violence.

Beyond the hemisphere, the United States projected power into China, joining other imperial powers in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion, and into the Pacific, using gunboat diplomacy to enforce commercial treaties. In every theater the hallmark was not restraint but escalation. Where opponents resisted, the United States used overwhelming force – burning villages, occupying capitals, and imposing direct control.

By the eve of World War I, the United States had become an unmistakable imperial power. Its reach extended across the Caribbean and Central America, into the Pacific and Asia, and onto the world stage in Europe. And the price was paid not only in annexed territory but in the blood of civilians subjected to massacres, scorched-earth campaigns, and military occupations.

World Wars and the Globalization of Violence

The entry into World War I projected American power onto the European continent for the first time, but the war was framed by what came before and after: the consolidation of empire in the Caribbean and the beginnings of global intervention. Marines still patrolled Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua even as American troops crossed the Atlantic. By 1918 the United States was both a European belligerent and a hemispheric occupier.

World War II is often remembered as the “good war,” but Toft and Kushi’s framework strips away the mythology. American bombing campaigns targeted cities and civilian infrastructure with devastating effect. In Europe, raids destroyed cultural centers like Dresden. In Asia, strategic bombing reached its apotheosis in the firebombing of Tokyo, which incinerated more than 100,000 civilians in a single night, and in the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These were not surgical strikes. They were deliberate acts of mass killing designed to terrorize populations into submission.

The Cold War transformed America’s global reach into a permanent system of intervention. Korea was the first testing ground. Between 1950 and 1953 the U.S. Air Force dropped more tonnage of bombs on the peninsula than it had on the entire Pacific during World War II. Cities and villages were flattened, dams and irrigation works destroyed, producing widespread famine and civilian deaths. The case narratives describe entire towns erased from the map.

Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos followed. The My Lai massacre, in which U.S. troops slaughtered hundreds of unarmed villagers, became emblematic of a war fought with pervasive disregard for civilian life. Napalm and Agent Orange were used indiscriminately, burning flesh and poisoning generations. Strategic hamlets, free-fire zones, and search-and-destroy missions blurred any line between combatants and civilians. The countryside was devastated, millions displaced, and the land itself poisoned.

At the same time the covert side of American power expanded. In 1954 in Guatemala, a U.S.-backed coup overthrew the elected government of Jacobo Árbenz. What followed was one of Latin America’s darkest chapters: a forty-year civil war marked by massacres of entire villages, forced disappearances, and a genocidal campaign against the Mayan population.

From East Asia to Latin America to the Middle East, the record is consistent. U.S. interventions escalated conflicts, empowered repressive regimes, and inflicted extraordinary violence on civilian populations. And the dataset shows what the narratives make visceral: in the majority of these confrontations it was the United States, not its adversaries, that chose escalation and inflicted the greater share of destruction.

Central America’s Dirty Wars

Nowhere is the brutality of U.S. intervention more visible than in Central America during the 1970s and 1980s. The Military Intervention Project records these episodes in detail, and the case studies give them human texture: scorched-earth campaigns, death squads, massacres, and systematic terror carried out by governments and paramilitaries armed, trained, or financed by Washington.

El Salvador’s US-backed government prosecuted its war with death squads that hunted down priests, nuns, teachers, and peasants. The 1981 El Mozote massacre, in which nearly a thousand civilians were slaughtered, is only the most infamous example. U.S. advisors trained the Atlacatl Battalion that carried it out, and successive administrations poured military aid into the country despite overwhelming evidence of systematic killings.

In Nicaragua, the U.S. sought to overturn the Sandinista government by funding and arming the contras. Their campaign of terror targeted civilians, burning schools and clinics, murdering teachers and health workers, and depopulating the countryside with indiscriminate violence. The International Court of Justice eventually condemned U.S. actions as unlawful aggression, but the policy continued for years, devastating the country.

Honduras became a staging ground for these operations. The U.S. military established bases and trained local security forces that carried out assassinations and disappearances against domestic opponents. The infamous Battalion 316, supported by U.S. advisors, ran a campaign of kidnappings and torture.

Across the region, the pattern was unmistakable. When popular movements sought reform or revolution, the United States responded with military force, coups, and proxy wars. The cost was borne by peasants, labor organizers, teachers, and clergy, who were systematically targeted by militaries and paramilitaries acting with U.S. support. The crimes were not incidental. They were the strategy: terrorizing populations into submission, destroying the social base of insurgency, and keeping governments aligned with Washington.

Latin America became a laboratory of repression. And it was all the more damning because the United States was not reacting to existential threats. These were small, impoverished countries. Their struggles threatened American dominance, not American survival. The wars were wars of choice, and the crimes were the price Washington was willing to exact to maintain control of its “backyard.”

Wars of Choice in the New American Century

The end of the Cold War did not bring an end to American interventionism. On the contrary, the pace quickened. The Military Intervention Project shows that nearly one-third of all U.S. interventions took place after 1991, and they were increasingly wars of choice against much weaker opponents. The pattern of disproportionate violence documented across earlier centuries continued into the present.

The 1991 Gulf War inaugurated the new era. U.S. airpower devastated Iraq’s infrastructure in a matter of weeks, targeting not only military sites but electricity grids, water treatment facilities, and bridges essential for civilian life. Tens of thousands of civilians died directly or indirectly from the bombing and its aftermath. The following decade of sanctions further destroyed Iraq’s economy and contributed to mass malnutrition and preventable deaths, especially among children.

The 2003 invasion of Iraq stands as the paradigmatic war of choice. Launched without a clear defensive justification, it toppled Saddam Hussein but unleashed chaos that killed hundreds of thousands. U.S. forces conducted night raids that killed civilians, detained tens of thousands without due process, and operated torture sites like Abu Ghraib, where prisoners were humiliated, beaten, and sometimes killed. The occupation fragmented the state, triggered sectarian war, and created the conditions for the rise of the so-called Islamic State.

Afghanistan, the longest war in U.S. history, followed a similar trajectory. After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, the occupation stretched for two decades. Night raids by U.S. and allied special forces repeatedly killed civilians, drone strikes hit weddings and funerals, and detention centers became notorious for abuse. Civilian casualties mounted year after year even as the war’s stated objectives shifted and receded. By the time of withdrawal, Afghanistan was left impoverished and unstable, with millions displaced.

Elsewhere, the U.S. turned increasingly to air campaigns and proxy wars. In 2011, NATO’s intervention in Libya, driven by American airpower, destroyed Muammar Gaddafi’s regime but left the country in ruins. Rival militias carved up territory, civilians bore the brunt of lawlessness, and the state collapsed into chaos. In Syria, U.S. military involvement fueled a brutal conflict that devastated entire cities like Raqqa, where bombardments leveled neighborhoods and killed thousands.

The era of drone warfare extended American violence across borders with little accountability. In Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia, drone strikes killed suspected militants but also countless civilians, spreading fear in rural areas where the constant buzzing of drones became a form of psychological terror. Families were obliterated at weddings and funerals, farmers struck in their fields, children killed in their homes. These were not accidents at the margins of precision warfare. They were the predictable consequences of a strategy that privileged remote killing over political solutions.

Across the globe, interventions destabilized entire regions. In West Africa, U.S. counterterrorism programs armed and trained militaries that later staged coups. In Somalia, interventions stretching from the 1990s to the present repeatedly produced cycles of violence, from the infamous Black Hawk Down incident to ongoing drone strikes and special operations. Even in Europe, interventions in the Balkans left a legacy of destroyed infrastructure and displaced civilians.

The post-Cold War interventions reveal most clearly what Toft and Kushi’s dataset proves statistically: these wars were not responses to existential threats. They were chosen. And in the overwhelming majority of cases, the United States used more force than its adversaries, escalating conflicts that might otherwise have remained local. The methods may have shifted – from scorched-earth to drones, from occupations to proxy wars – but the results were the same: shattered states, traumatized societies, and civilians paying the highest price.

Conclusion: The Arithmetic of Empire

Monica Duffy Toft and Sidita Kushi have done something rare. They have replaced myth with measurement. By assembling the most comprehensive dataset of U.S. military interventions ever created, they show in black and white what generations of victims already knew in blood and fire. The United States has not been a reluctant warrior. It has been the most interventionist power in modern history – rivalled only by the British Empire.

Even in its budgetary priorities, the imbalance is clear. The authors note that State Department spending – a rough proxy for diplomacy and peaceful engagement – has crept up only slowly from about 1 percent of Defense Department spending in the 1960s to around 4 or 5 percent in recent years. The pattern is unmistakable: the United States has consistently poured multiple times more resources into war-making than into diplomacy.

The figures are devastating. Three hundred and ninety-two interventions from 1776 to 2019. The trend is unmistakable. As America grew stronger, it intervened more often. And the methods were not defensive. In the vast majority of cases the United States used more force than its adversary. Time and again, it was Washington that escalated, that bombed, that occupied, that tortured. Its enemies, when they fought at all, were usually far weaker, and the overwhelming share of destruction was inflicted by American hands.

The case studies expose the human cost. They are not isolated aberrations. They are the record of a state that has consistently used its power to dominate, to coerce, and to destroy. The book’s great achievement is to prove this not just through narrative but through data. The dataset is the skeleton, the case studies the flesh. Together they show a nation that has institutionalized military intervention, made violence a default tool of policy, and exported suffering on a global scale.

Dying by the Sword is more than a history. It is an indictment. It demands that Americans and the world alike face a truth too long obscured by rhetoric about freedom and democracy: the United States has built its global position not on hesitant leadership, international law or human rights; but on repeated, aggressive wars of empire. And in those wars, it has too often been the author of the greatest crimes.

You can find Michael’s interviews with Jeffrey Sachs, Trita Parsi, Scott Horton and other antiwar voices on his author’s page for NachDenkSeiten — the videos are in English!

Michael Holmes is a German-American freelance journalist specializing in global conflicts and modern history. His work has appeared in Neue Zürcher Zeitung – the Swiss newspaper of record – Responsible Statecraft, Psychologie Heute, taz, Welt, and other outlets. He regularly conducts interviews for NachDenkSeiten. He has reported on and travelled to over 70 countries, including Iraq, Iran, Palestine, Lebanon, Ukraine, Kashmir, Hong Kong, Mexico, and Uganda. He is based in Potsdam, Germany.