Petty Officer 3rd Class Jonathan Lally/U.S. Coast Guard/File

The 420-foot U.S. Coast Guard cutter Healy breaks ice in the Bering Sea to assist the tanker Renda, approximately 165 miles from Nome, Alaska, Jan. 8, 2012.

LONG READ

October 12, 2021

By Sara Miller Llana Staff writer

RESOLUTE BAY, NUNAVUT

Steering the ship from her perch 93 feet above the Arctic waterline, U.S. Coast Guard Ensign Valerie Hines guides the vessel through ice cover laid out like a vast white puzzle starting to tear apart.

She nudges the 420-foot U.S. Coast Guard cutter Healy forward – ramming, then backing up and ramming again, the ice that is several feet thick. The noise is deafening as cleaved chunks scrape the side of the hull. Below deck, the constant vibration caused by the severing sheet can feel like an earthquake.

Yet the bulldozing task here has its moments of beauty, too: Some of the ice chunks peeling away from the bow glow with an iridescent blue, as if being lit by a flashlight from underneath the sea.

WHY WE WROTE THISWith the melting Arctic opening up new opportunities and stirring old rivalries, the U.S. and Canada are trying a cooperative approach to tapping the thawing resources and trade routes. Part one of two.

The ship’s journey is part of a rare transit through the fabled Northwest Passage that is helping the U.S. project influence in what is one of the most geostrategic – and quickly changing – places on Earth.

With a warming Arctic and polar ice cap in retreat, the rooftop of the world is more navigable than at any time in modern history. And that is opening up the potential for new commercial lanes and the need for better search and rescue expertise, enhanced environmental protection, and cooperation with local populations in the high latitudes. It has also set off a global race to lay claim to routes and resources in the austere but all-important region.

Chief Petty Officer Matt Masaschi/U.S. Coast Guard

Ensign Valerie Hines pilots the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Healy through the ice during its Northwest Passage transit, Sept. 2, 2021. “One of the things I’ve learned is just how much patience icebreaking requires,” says Ensign Hines.

“They are pretty crazy pieces of ice,” says Ensign Hines. “They would roll down the side of the hull and you would see them flip over on their side, back behind us. It’s definitely a multisensory experience.”

But, first, Ensign Hines has to actually get the Healy through the entombed tundra. It’s the ship’s third journey across the Northwest Passage. Ensign Hines says piloting the bull-nosed boat through the ice field takes composure and problem-solving: deciding when and how far to veer off a particular path, sometimes weaving and sometimes turning sharply through a multiyear ice field. Other times the best option is simply to batter ahead.

“One of the things I’ve learned is just how much patience icebreaking requires,” says Ensign Hines.

No ice to stand on

That knowledge is one of the main points of this voyage through the Northwest Passage, which was first traversed by a Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen, in 1906. Since Mr. Amundsen’s first voyage, only 318 vessels, as of 2020, have successfully crossed it.

More than two-thirds of those crossings have happened in the past 15 years, amid changes the Healy has witnessed. When the ship took its maiden voyage through the Northwest Passage in 2000, the Arctic had about a quarter more ice cover. Looking over time, the trend lines are clear. It’s declining by 13% per decade.

This decline is part of every consideration and conversation that happens in this part of Canada, from the most profound to the most mundane. Here in Resolute Bay, one of the most northerly communities in the world, where Inuit were forcefully relocated by the Canadian government beginning in 1953 to exert sovereignty in the High Arctic, unstable ice has upended everything from hunting patterns and the availability of food to hockey tournaments normally reached by snowmobile over frozen ice.

At sea, the changes are felt not just by ice pilots and scientists. U.S. Coast Guard electrician’s mate Master Chief Petty Officer Mark Hulen, whose job it is to power the Healy, was on the ship’s maiden voyage, and made a handful of Arctic journeys since. This latest trip is the first time the crew hasn’t been able to get “ice liberty”: That’s when they’ll put out a lookout for polar bears and let the crew climb out and stretch their sea legs on a berg of ice, usually about a half mile or longer. There’s always a few who start an impromptu football game. “We really did struggle with finding a good enough piece of ice to stand on,” he says.

Petty Officer 3rd Class Janessa Warschkow/U.S. Coast Guard

Healy crew launch an unmanned underwater vehicle under the sea ice in the Chukchi Sea, Aug. 5, 2021.

The Arctic is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the globe, and some scientists warn that within the next two decades the waterways could be ice-free in summertime. That has generated new tensions over Russian militarization of the Arctic, a hungry China vying for its resources, and increased competitions for sea lanes.

Even this passageway is contested: Canada views the Northwest Passage as an internal waterway, while the U.S. claims it’s an international seaway. The dispute remains, managed under a 1988 accord that requires the U.S. to seek prior consent from Canada before passage, but tensions flared under the Trump administration. The Americans floated what’s called a “freedom of navigation operation” and called Canada’s claim to the Northwest Passage “illegitimate.”

The Healy passage, which sought prior consent and contains a strong science focus, is about shoring up the U.S. partnership with its Arctic allies, as well as expanding its understanding of what’s happening in the region. Passengers include military counterparts from Canada, Denmark, and Britain carrying out joint exercises, while a plethora of scientists conduct international research crucial to understanding the implications of climate change. The vessel is expected to arrive in Boston Oct. 14, its first U.S. port since leaving Alaska in August.

“We’re demonstrating the U.S. ability to increase our reach in the Arctic,” says Adm. Karl L. Schultz, commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard. “It’s building our organic knowledge in the area. It’s projecting our interests. It’s demonstrating to the other nations of the world that like-minded partners are collaborating and working in this important space.”

Sara Miller Llana/The Christian Science Monitor

Adm. Karl L. Schultz, commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, is in the Northwest Passage in Resolute Bay, Nunavut, to watch the Healy make a rare transit.

Both the U.S. and Canadian coast guards have sought to expand their Arctic capabilities in recent years. The U.S. Coast Guard only has two operable icebreakers, a heavy breaker that is aging and requiring expensive upgrades, and the medium breaker Healy. Its Polar Security Cutter program foresees three new heavy polar icebreakers, two of which are fully funded. The first is currently under contract.

Amid the talk of warming, Admiral Schultz says he regularly fields the question: Why then the need for more icebreakers? “I think right now, because presence equals influence and we have very little presence, that’s not a hard conversation for me,” he says, adding that a warming Arctic means a more unpredictable one, because of ice that is rougher and behaves differently.

It also means a more open Arctic, which will mean more cruise liners, recreational boaters, and adventurists, which the Canadian Coast Guard must rescue.

Canada’s Coast Guard, which is not part of the Canadian military but in charge of search and rescue and environmental protection, expanded its presence here three years ago, creating a permanent outpost in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. It is doing so in cooperation with allies, but a main mission is to support and cooperate with the Inuit population at the frontlines of climate change, says Neil O’Rourke, the assistant commissioner, Arctic region at Canadian Coast Guard.

“It’s going to clobber us over and over”

All of this can feel far away from the reality of most Canadian and American lives.

Despite the Arctic comprising more than 40% of Canadian landmass, two-thirds of Canadians live within 100 kilometers of the U.S. border. The U.S. Arctic region is much smaller and farther away from most Americans.

Larry Mayer, founding director of the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping at the University of New Hampshire, is the lead scientist on the Healy. An oceanographer from the Bronx who was inspired by the book “Boy Beneath the Sea,” today he is essentially a modern-day charter, mapping the seafloor for a project called Seabed 2030.

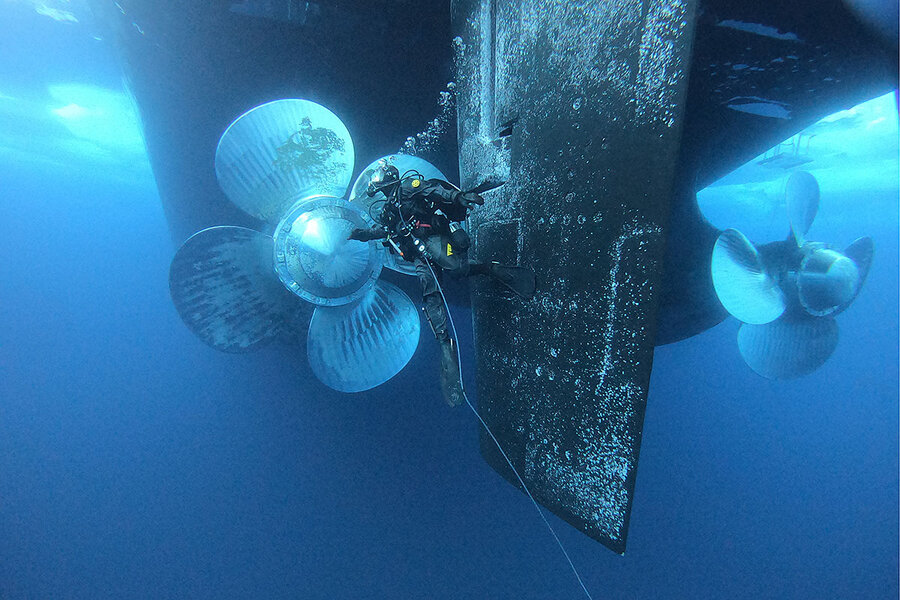

Petty Officer 2nd Class Connor Dahl/U.S. Coast Guard

Senior Chief Petty Officer Donald Selby participates in a dive beneath the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Healy in the Chukchi Sea, between Russia and Alaska, Aug. 5, 2021.

Only about 14% of the Arctic has been mapped – and he has just completed a corridor of the Northwest Passage. While knowing the contours of the seafloor is crucial for vessel safety, everything done here has implications felt well beyond this sea lane. Open waters affect the nature of wind patterns and the transfer of heat – which are felt well beyond the Arctic circle.

“The Arctic is having a severe impact on storminess in North America and a lot of the anomalous weather patterns that we’ve seen are really a direct result of that,” he says. “It’s just such a complex system of interconnectivity.”

As he wraps up a talk on his work aboard Healy, and the U.S. and Canadian coast guards await a helicopter transfer back to Resolute Bay, the discussion quickly turns to the fatal flooding of basement apartments in New York City in the wake of Hurricane Ida and the rest of the weather events grabbing global headlines.

“Something is different,” Dr. Mayer says. “And if we don’t own up to it, it’s going to clobber us over and over.”

Admiral Schultz calls himself “agnostic” on the climate debate. But he wants Americans to understand what they are doing up here is not an “esoteric, long-way-from-home kind of topic,” he says. “There’s more water, and there’s water where there didn’t used to be water. The practical reality is, there is a crescendo of knowledge that things are changing.”

Next: In Murmansk, icebreakers are also the center of attention as the Kremlin looks to turn the Northeast Passage into a major shipping route and the Russian port city into an economic powerhouse.

No comments:

Post a Comment