Europe’s Juice spacecraft lifts off to explore Jupiter’s moons

A European spacecraft is on its way to Jupiter in a mission to explore whether its ocean-bearing moons can support life.

The six-tonne probe, named Juice (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer), blasted off on an Ariane 5 rocket on Friday at 1.14pm UK time from the European spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana.

Juice was due to take off on Thursday but weather conditions showed there was a risk of lightning.

The spacecraft is now making a 4.1 billion-mile journey which will take more than eight years.

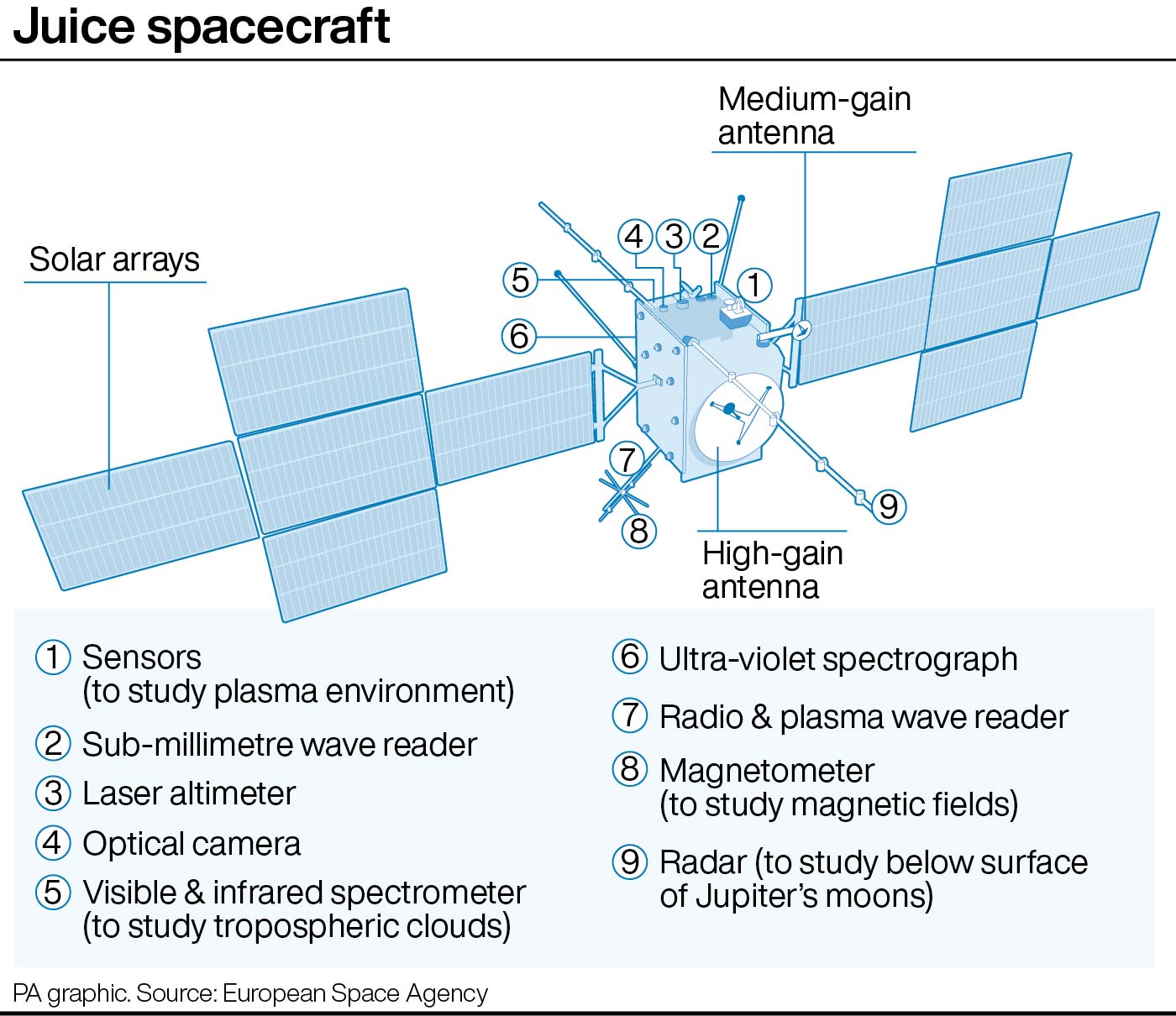

Onboard are 10 scientific instruments, which will investigate whether the gas giant’s three moons – Callisto, Europa and Ganymede – can support life in its oceans.

Professor Leigh N Fletcher, from the University of Leicester’s school of physics and astronomy, who has been involved in the Juice mission since 2008, described the launch as a “heart-stopping moment”.

Prof Fletcher, who watched the launch from the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany, said: “What an amazing, heart-stopping moment to watch the launch from here in ESOC, alongside colleagues who were dreaming of a mission to Jupiter for the last 15 years.

Three researchers from the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies contributed to the mission.

Professor Caitriona Jackman, Dr Mika Holmberg and Dr Corentin Louis were in Germany to witness the launch.

"The launch is a culmination of years and decades of work from scientists and engineers across Europe and across the whole world," Prof Jackman ahead of today's launch.

"We are really, really excited for a successful launch and a successful mission."

Professor Andrew Coates, of the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London, is a co-investigator on two of Juice’s 10 scientific instruments: PEP, which will gather data on the atoms surrounding Jupiter and its moons, and Janus, the spacecraft’s optical camera system.

He said: “It’s so exciting to see Juice safely on its way to Jupiter, so far so good, a great launch on Ariane 5, and all nominal so far with separation confirmed!

“We can’t wait to start exploring Jupiter’s magnetosphere in 2031, look at Europa, Ganymede and Callisto during flybys, and orbit Ganymede in 2034.

“We are privileged to have helped define the mission and to be part of the PEP and Janus teams.”

Meanwhile, Dr Chiaki Crews, research fellow at The Open University, who has also been involved in testing the Janus, said: “We’re delighted and relieved to see that Juice has launched successfully, and it’s exciting to think that the Janus camera’s sensor that once sat in a clean room at the Open University is on board the spacecraft!”

Scientists from Imperial College London have led the development of one instrument, known as the magnetometer.

Called J-MAG, it will measure the characteristics of magnetic fields of Jupiter and Ganymede – the only moon known to produce its own magnetic field.

Juice will perform a manoeuvre known as gravitational assist, where it will use the gravity of Earth and Venus to slingshot toward Jupiter.

At its destination, the spacecraft will spend at least three years making detailed studies of Jupiter, Ganymede, Europa and Callisto.

Juice is not equipped to search for signs of life but its aim is to explore the conditions that could support life.

Beneath the ice crust of Europa is thought to lie a huge ocean of liquid water, containing twice as much water as Earth’s oceans combined.

But scientists are more interested in Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, which is thought to have a salty ocean beneath its icy shell.

One of Juice’s key goals is to explore this body of water and determine whether this world may be habitable.

Data gathered from the J-MAG instrument will help characterise the depth and salt content of Ganymede’s ocean.

Juice has been built to withstand harsh radiation and extreme conditions, ranging from 250C around Venus to minus 230C near Jupiter.

Sensitive electronics are protected inside a pair of lead-lined vaults within the body of the spacecraft.

If all goes well, Juice should reach Jupiter in July 2031 and will have enough fuel to make 35 flybys of the icy moons before orbiting Ganymede from December 2034.

Once the spacecraft runs out of fuel, Juice will perform a controlled crash into Ganymede, marking the end of the £14 billion (€15.9bn) mission.

Mission to find life on Jupiter’s moons blasts off on eight-year journey

The European Space Agency’s mission to Jupiter’s moons has made the first step on its 4.1billion-mile journey with a successful launch.

Hitching a ride on an Ariane 5 rocket, the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) spacecraft blasted off from the ESA’s spaceport in French Guiana at around 1.15pm. The launch was originally scheduled for Thursday, but was postponed due to the weather.

Large crowds gathered to watch the lift-off, but the launch rocket was quickly obscured by cloud cover. Those watching online were treated to a 3D animation of the rocket’s journey.

Shortly after launch the rocket’s solid boosters detached successfully, followed by jettisoning of payload fairing – the nose of the rocket that protected JUICE during take-off.

After almost 30 minutes, the JUICE spacecraft safely separated from its launch vehicle to begin a long solo journey, and around 50 minutes after lift-off the control room filled with relieved applause as the spacecraft began transmitting back to the ground.

The aim of the mission is to search for signs of life in the liquid oceans beneath the icy exteriors of Ganymede, Callisto and Europa, three of Jupiter’s more than 90 moons.

While Jupiter itself is 891million miles from Earth, the spacecraft cannot carry enough fuel to carry it directly to the Gas Giant. Instead, JUICE will make flybys around Earth and Venus to slingshot it deep into the solar system. The journey of more than 4billion miles will take almost eight years to complete.

Once reaching Jupiter, JUICE will make 35 flybys of the three large moons while orbiting the planet, before changing orbits to Ganymede.

A British team developed one of the key pieces of equipment for detecting life in the moons’ liquid oceans – a magnetometer.

Built in London’s Imperial University labs – and in people’s homes – over lockdown, the instrument will be key in investigating what lies beneath the ice.

‘The hardest thing that we are aiming to do is to try and measure the magnetic field from electrical currents that are flowing in the liquid water ocean on Ganymede,’ said Professor Michele Dougherty, principal investigator for the magnetometer aboard JUICE.

‘That’s going to allow us to work out not only the depth of the ocean, but its salt content and hopefully get an idea about whether it’s a global ocean or whether it’s only focused at part of the moon.

‘We’re almost certain that at least three of the moons have good liquid water oceans underneath the surface. If we are looking for places in our solar system, where life can form, the first ingredient you’re looking for is liquid water.’

The hope is that JUICE will confirm this, plus a heat source and organic material on these moons.

‘Those three ingredients – liquid water, heat and organic material – are first needed, we think, for life to form. If those are stable enough over a long enough period of time, then potentially something might be able to happen.’

MORE : Return to Jupiter: Meet the British team searching for life on the Gas Giant's moons

MORE : Jupiter replaces Saturn as the planet with the most moons, with 12 new ones