Australia Reports on Bulker’s Engine Shut Down in Busy Port Hedland

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) has released its interim report on the incident involving bulk carrier FMG Nicola (260,840 dwt) while departing Port Hedland in Western Australia in February this year. It details how an iron ore carrier nearly caused a major blockade of a busy shipping channel that provides access to the world’s largest bulk export port, and the quick response.

The 327-meter (1,073-foot) Singapore-flagged vessel lost propulsion after her engine shut down due to what investigators have established was a faulty switch monitoring the main engine’s lubricating oil pressure. The ship, fully laden with iron ore, was saved from grounding by tugs and the fast response of the pilot overseeing the outbound trip.

The massive vessel, which was built in 2016 and operates for Australia’s Fortescue Metals Group, could easily have blocked the busy channel that provides access to Port Hedland. It is the world’s largest bulk export port by tonnage, handling over 500 million tonnes of cargo annually. While more than 95 percent of the volume is iron ore, the port also handles exports of salt, manganese, copper concentrates, lithium minerals, and livestock, with more than 6,000 ship movements each year.

Access to Hedland is through the single 22?mile dredged channel that allows only one large ship to pass at a time. For most laden ships, particularly capesize ships such as FMG Nicola, the use of the channel is restricted by tidal conditions. The incident, which happened on February 7, took place within the 10?mile section of the channel that is closest to the port, an area prone to strong tidal flows and with particularly confined spaces.

“A disabled ship can strand on a receding tide as well as blocking the passage of other ships. Depending on departure times, separation between ships and the location of an incident, up to three additional ships could be committed to, or within, the channel and exposed to this hazard at a given time,” said Angus Mitchell, ATSB Chief Commissioner.

Though the investigation is ongoing, ATSB’s interim report provides the details of the incident involving Nicola and a well-organized response. At 0832 local time, the bulker completed loading over 237,000 tonnes of iron ore at its berth in Hedland and was due to depart for Dongjiakou, China, that same afternoon.

By 1348, the ship’s main engine and steering had been tested, and the master-pilot information exchange was completed in preparation for the departure. Four tugs were secured to assist the ship through the port’s single shipping channel. The ship departed at 1412, and 30 minutes later, she was progressing along the channel as planned.

At about 1516, FMG Nicola’s main engine suddenly shut down while she was moving at a speed of 8.3 knots. The pilot quickly informed the tug masters that the ship had lost propulsion and directed them to help keep it in the channel. Luckily, two tugs were still secured, and a third was nearby.

The report highlights that the engine had shut down due to a faulty switch monitoring the main engine’s lubricating oil pressure. Over the next half hour, the ship neared the western and then the eastern side of the channel, before travelling along the channel’s eastern edge as it slowed gradually. The efforts by four tugs prevented the ship from grounding, something that would have resulted in blocking the channel.

The ship’s engineers identified that the engine had shut down as the “main bearing and thrust bearing lubricating oil pressure low” non?cancellable trip had activated. They determined that it had activated due to the faulty operation of the pressure switch. After confirming all engine systems were operating normally, the engine trip lockout system was reset and, at 1523, the engine was restarted at dead slow ahead.

About 35 minutes after the shutdown, the ship had been moved away from the channel side, and its main engine speed had progressively been increased to full ahead, enabling the ship to continue her voyage to China. No damage or injuries occurred during the incident.

ATSB will publish its final report detailing the analysis and findings upon the conclusion of the investigation.

Troubled Ferry Glen Sannox Pulled From Service Over Repeated Cracking

CalMac's ill-starred ferry Glen Sannox is suffering repeated hull cracking issues just eight months after delivery, and the problem is related to an unresolved and severe vibration issue in her propulsion system, according to Scottish paper The Herald.

It has been a long road for the Glen Sannox project, and an illustration of the difficulties of starting a national shipbuilding program. Shipyard Ferguson Marine started work on the CalMac ferry in 2015, went bankrupt after serious design flaws emerged, and was nationalized in 2019. After a long saga of rework, budget hikes and personnel changes, the ferry finally entered service in January 2025, six years behind schedule and four times over budget. It has been in and out of repair status ever since.

In March, Glen Sannox was pulled from service after a five-inch-long hairline crack was discovered in a weld seam on the hull, in way of the steering gear compartment near the waterline. Repairs were completed shortly after, and following a dive inspection the ferry was cleared to sail again.

Last week, a new crack was discovered in the same area, and the Glen Sannox has been pulled from service through at least October 13. The Herald reports that CalMac is consulting with marine engineering experts at home and abroad in search of a permanent solution. The crack is believed to be caused by a vibration issue in the same specific area.

Passengers confirmed that the ship had severe vibration at the stern during certain evolutions. "Anyone who has been on the ship, particularly in the aft end of passenger space while maneuvering, could have worked that out," commented passenger Sam Bourne, a local resident, in a social media post. "It was vibrating so badly it would literally shake the coffee out of your cup."

One passenger video shows the rails of a ladderway visibly shaking from heavy vibration near the stern.

The source of the vibration has not been published, but the Herald reports that it is related to a propeller issue. Glen Sannox is fitted with a stern thruster to help handle strong currents and winds on the beam, and she has twin controllable pitch propellers.

TSB: Barge Stability Drops Off Dangerously When Overloaded

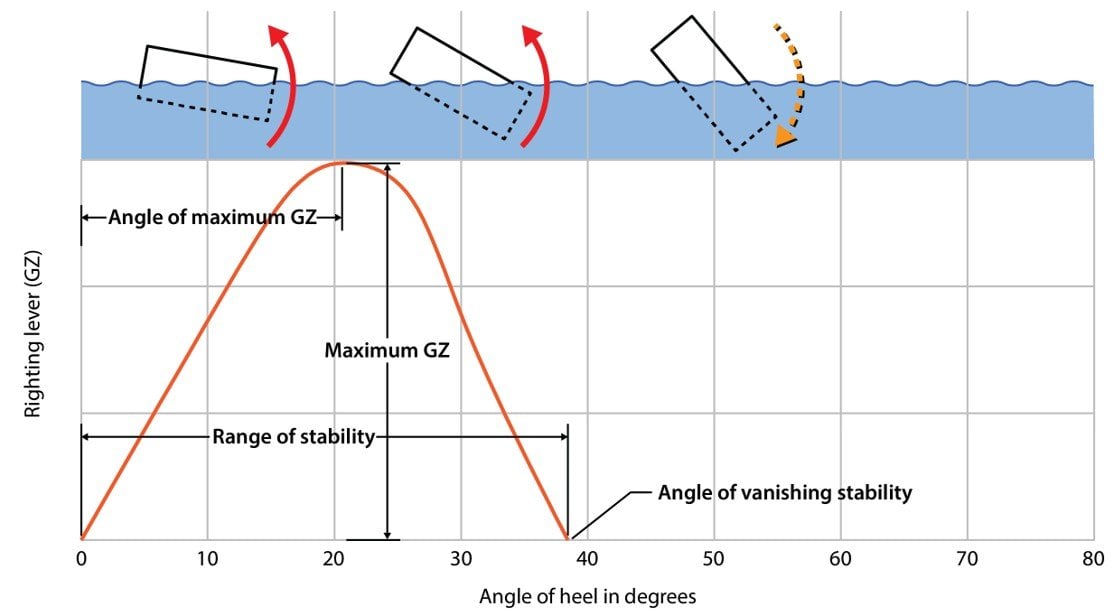

Canada's Transportation Safety Board is advising mariners to keep in mind the differences in stability between flatbottomed barges and seagoing hull shapes. A properly-loaded barge is highly stable at low angles of heel, but its righting moment tails off sooner and more abruptly than a ship's, leaving it vulnerable to capsizing once tipped - as experienced by the crew of the Arctic sealift ship Sivumut at Iqaluit, Nunavut two years ago.

The Sivumut is a geared freighter used to serve outposts in the Canadian Arctic. It carries two deck barges, Tasijuaq I and II, which are used for lightering off cargo for delivery to coastal villages. Upon deployment, the two barges are lashed together into a single unit with rods, hooks and cleats, and used as a single vessel throughout the operating season. The cargo is loaded towards the center of the barge and is not secured before making a gentle tow to shore, where the barges are beached and the cargo removed.

On October 27, Sivumut's crew were offloading cargo in Frobisher Bay, a sheltered inlet near Iqaluit. The shipowning company's CEO was on board for a visit.

At about 1430, in a routine evolution, they laid down 12 containers on the barge Tasijuaq's deck alongside the ship, then another tier of 12 on top. At this point, the barge was carrying about 340 tonnes and listing slightly to port. When the tug came alongside and took the barge on the hip for transit to shore, the tug's bow bumped into the barge's starboard side. Tasijuaq heeled to port; swayed back; then slowly heeled to port again and kept going.

As the unsecured cargo on deck slid to port, the barge began to capsize. The lines connecting it to the tug parted, and 23 out of 24 containers went into the water, along with a deckhand from the tug. As the barge's load lightened, it righted itself and returned to upright.

The tug master cast off the remains of the lines and went searching for the deckhand, who was drifting in ice-cold water along with the containers. He was found unconscious within about five minutes, floating with his PFD inflated. The tug master jumped atop a floating container to reach and retrieve him, and with the assistance of other crewmembers, he hauled the deckhand up onto the container. The victim was injured and suffering from hypothermia, and was treated by local physicians before a medevac to Ottawa for higher care.

The barge was retrieved promptly after the deckhand was recovered, and the crew immediately went after the lost cargo. Ultimately 10 boxes were recovered in a dynamic operation over several days; the remainder had to be left because the navigation season was ending and winter conditions were coming.

After the casualty, TSB calculated that the barge (as laden) had a positive GM of about two feet, and an angle of vanishing stability of less than three degrees of heel - after which it would likely capsize. This is a fraction of the 20-degree international code requirement for small barges, even if the barge's GM was positive.

Tasijuaq was carrying about 130 tonnes more than it was rated for in its structural arrangement plan, a copy of which was not carried aboard (carriage is not required by Canadian law). The crew and the master were not aware of the barge's limitations as described in the plan.

"Vessels with relatively wide hulls and flat bottoms, such as barges, typically have a higher initial GM and a steep righting lever (GZ) curve (peaks at smaller angles), and the range of stability is much less than a traditionally shaped vessel," TSB cautioned. "It is therefore important to ensure that the stability characteristics and loading limits are established and that the cargo crew are familiar with them."

GZ versus angle of heel for a typical flat-bottomed barge (TSB)

No comments:

Post a Comment