SPACE/COSMOS

More Chinese Rocket Debris Washes Up in the Philippines

China's Long March rocket program has a launch site on Hainan Island, and a history of dropping debris over the South China Sea. According to the Philippine Coast Guard, more waste from a Chinese booster rocket has washed up on an island in the Taiwan Strait, and it has been recovered for analysis.

On Sunday, local residents were walking on the shore near Minabel, a town on the north side of Camiguin Island. They spotted metallic debris on the shore and stopped to investigate. The local Philippine Coast Guard station (and other agencies) responded to the scene to recover the waste, which appears to be panel sections from the exterior of a booster rocket.

As in previous cases, the PCG advised local residents not to touch any related debris because of the potential risk of chemical exposure: the rocket fuel used in some Chinese booster designs is known to be toxic.

It is the latest in a long run of Chinese rocket debris finds in the Philippines, and is a product of the design and operation of China's orbital launch rockets. Previous debris finds in the Philippines included a large panel that was found off Occidental Mindoro, likely from a Long March 7 launch in July. There may be more coming: another Long March rocket was launched on November 3 and likely dropped its booster debris in the water about 75 nm to the east of Camiguin Island, according to the Philippine Space Agency.

"While not projected to fall on land features or inhabited areas, falling debris poses danger and potential risk to ships, aircraft, fishing boats, and other vessels that will pass through the drop zone," the Philippine Space Agency warned.

Overseas space agencies perceive the greatest hazards from from the occasional launches of the Long March 5B. This rocket's big first stage booster goes into orbit as a single piece, but lacks any capability for controlled reentry when it comes back down. The entire booster de-orbits in an uncontrolled manner, breaks up and scatters debris over a wide area. The practice has attracted criticism from NASA, as the uncontrolled-reentry method is seen as risky and is no longer done in the West.

Was 3I/ATLAS sent by aliens? Why the comet from another world continues to baffle

The mystery surrounding 3I/ATLAS has captured the imagination of many, from leading astronomers to pop culture A-listers like Kim Kardashian and tech mogul Elon Musk.

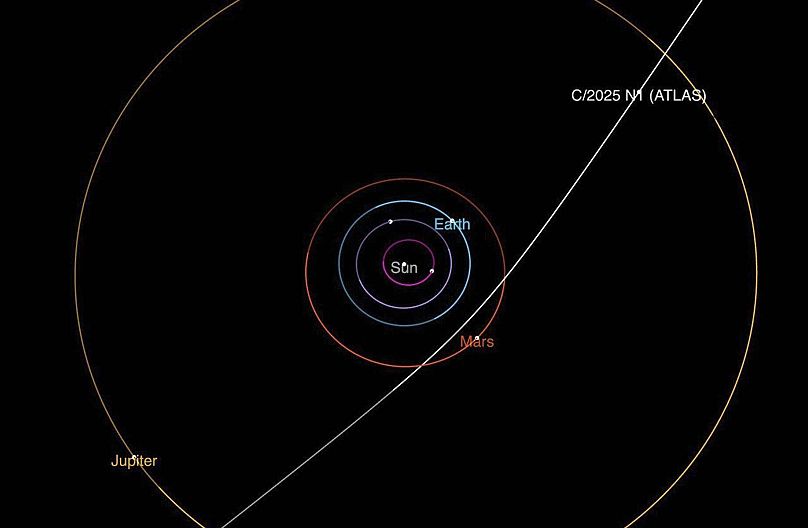

When astronomers first spotted 3I/ATLAS on 1 July 2025 using the ATLAS survey telescope in Chile, it was immediately clear that this was no ordinary space rock.

As only the third confirmed interstellar object ever recorded - after ʻOumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019 - 3I/ATLAS sparked attention for its icy core enveloped by a coma, the luminous halo of gas and dust.

Its speed and trajectory show that it’s not gravitationally bound to the Sun - meaning it must have originated in another star system and wandered into ours by chance.

While NASA officially identified 3I/ATLAS as a comet and not an asteroid last week, some scientists, most prominently Professor Avi Loeb, a theoretical astrophysicist at Harvard University, has suggested its unusual features could hint at signs of alien technology.

And as it swooped to its closest point to the sun in late October (perihelion), 3I/ATLAS began acting in ways that have astronomers scratching their heads again.

Bizarre observations

Most strikingly, the comet experienced a non-gravitational acceleration near perihelion, moving faster than gravity alone would allow.

Observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) showed the comet was 4 arcseconds off its predicted trajectory, according to a recent blog post by Loeb in Medium.

Ordinary comets are nudged slightly by the gases released from their icy surfaces, but the motion of 3I/ATLAS was unusually strong.

Meanwhile, its colour shifted dramatically - from a reddish hue to a deep blue - something atypical for comets, which usually redden as sunlight scatters through dust around them.

Astronomers also recorded a sudden brightening in the days before perihelion, suggesting massive amounts of material were being ejected - possibly as surface ice vaporised under the intense solar heat.

Speculation and reactions: From Elon Musk to Kim Kardashian

The unusual behaviour has reignited speculation about whether 3I/ATLAS could be more than a natural comet.

Loeb has suggested in a recent blog post that "the non-gravitational acceleration might be the technological signature of an internal engine."

He added that if no massive gas cloud is observed around the comet in December, "then the reported non-gravitational acceleration near perihelion might be regarded as a technological signature of a propulsion system."

Pop culture and public figures have also chimed in to the debate. Kim Kardashian tweeted to NASA asking for clarification on 3I/ATLAS, prompting a reassuring reply from acting administrator Sean Duffy:

"Wait … what’s the tea on 3I/ATLAS?!?!!!!!!!?????," asked Kardashian.

Duffy replied: "Great question! NASA’s observations show that this is the third interstellar comet to pass through our solar system. No aliens. No threat to life here on Earth."

Meanwhile, Space X and Tesla CEO Elon Musk discussed the comet on The Joe Rogan Experience, speculating that its massive size and its unusual composition could be catastrophic if it were ever on a collision course with Earth.

Musk noted that while 3I/ATLAS isn’t threatening now, its potential to cause continental-scale damage cannot be ignored.

Extremely massive stars forged the oldest star clusters in the universe

A new model explains the long-standing chemical mysteries of globular clusters, the ancient archives of the universe

image:

On the left, an artist’s impression of a globular cluster near its birth, hosting extremely massive stars with powerful stellar winds that enrich the cluster with elements processed at extremely high temperatures. On the right, an ancient globular cluster as we observe it today: surviving low-mass stars retain traces of the winds from those extremely massive stars, which have since collapsed into intermediate-mass black holes.

view moreCredit: Fabian Bodensteiner; background: image of the Milky Way globular cluster Omega Centauri, captured with the WFI camera at ESO’s La Silla Observatory.

An international team led by ICREA researcher Mark Gieles, from the Institute of Cosmos Sciences of the University of Barcelona (ICCUB) and the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia (IEEC), has developed a groundbreaking model that reveals how extremely massive stars (EMS) — with more than 1,000 times the mass of the Sun — have governed the birth and early evolution of the oldest star clusters in the universe

The study, published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, reveals how these short-lived stellar giants profoundly influenced the chemistry of globular clusters (GCs), which are some of the oldest and most enigmatic star systems in the cosmos.

Globular clusters: the ancient archives of the universe

Globular clusters are dense, spherical groups of hundreds of thousands or millions of stars found in almost all galaxies, including the Milky Way. Most are more than 10 billion years old, indicating that they formed shortly after the Big Bang.

Their stars display puzzling chemical signatures, such as unusual abundances of elements like helium, nitrogen, oxygen, sodium, magnesium, and aluminium, which have defied explanation for decades. These “multiple populations” point to complex enrichment processes during cluster formation from extremely hot “contaminants”.

A new model for cluster formation

The new study is based on a star formation model known as the inertial-inflow model, extending it to the extreme environments of the early universe. The researchers show that, in the most massive clusters, turbulent gas naturally gives rise to extremely massive stars (EMS) weighing between 1,000 and 10,000 solar masses. These EMSs release powerful stellar winds rich in high-temperature hydrogen combustion products, which then mix with the surrounding pristine gas and form chemically distinct stars.

“Our model shows that just a few extremely massive stars can leave a lasting chemical imprint on an entire cluster,” says Mark Gieles (ICREA-ICCUB-IEEC). “It finally links the physics of globular cluster formation with the chemical signatures we observe today.”

Researchers Laura Ramírez Galeano and Corinne Charbonnel, from the University of Geneva, point out that “it was already known that nuclear reactions in the centres of extremely massive stars could create the appropriate abundance patterns. We now have a model that provides a natural pathway for forming these stars in massive star clusters.”

This process occurs rapidly — within one to two million years — before any supernova explodes, ensuring that the gas in the cluster remains free from supernova contamination.

A new window onto the early universe and black holes

The implications of the discovery extend far beyond the Milky Way. The authors propose that the nitrogen-rich galaxies discovered by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) are likely dominated by EMS-rich-globular clusters), formed during the early stages of galaxy formation.

“Extremely massive stars may have played a key role in the formation of the first galaxies,” adds Paolo Padoan (Dartmouth College and ICCUB-IEEC). “Their luminosity and chemical production naturally explain the nitrogen-enriched proto-galaxies that we now observe in the early universe with the JWST.”

These colossal stars are likely to end their lives collapsing into intermediate-mass black holes (more than 100 solar masses), which could be detected by gravitational wave signals.

The study provides a unifying framework that connects star formation physics, cluster evolution, and chemical enrichment. It suggests that EMSs were key drivers of early galaxy formation, simultaneously enriching globular clusters and giving rise to the first black holes.

.

Journal

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Globular cluster formation from inertial inflows: accreting extremely massive stars as the origin of abundance anomalies

Article Publication Date

4-Nov-2025

Robotic exosuit trousers could boost astronauts’ movement in space missions

Peer-Reviewed Publicationimage:

The artificial muscles in the suit consist of two layers: an outer nylon layer and an inner thermoplastic layer that allows airtight inflation. The anchoring components, such as the waistband and knee straps, are made from Kevlar for high strength and tension resistance.

view moreCredit: Dr Emanuele Pulvirenti

Astronauts could soon be able to move more freely thanks to a soft robotic exosuit developed by researchers at the University of Bristol.

Not only does the technology have extraterrestrial benefits, but it could also help people who need support with their mobility on earth too.

The soft robotic exosuit is designed to resemble a garment and is mostly made of fabric material. Worn underneath the spacesuit, the exosuit features artificial muscles that work automatically to help astronauts reduce muscular fatigue while maintaining natural movements during future Moon and Mars missions.

Last month, Dr Emanuele Pulvirenti, Research Associate in the University of Bristol’s Soft Robotics Lab, travelled to the University of Adelaide, Australia, home to the Exterres CRATER facility – the largest simulated lunar environment in the Southern Hemisphere.

Here the exosuit was tested as part of an international ‘proof of concept’ simulated space mission run by the Austrian Space Forum. Dubbed the ‘World’s Biggest Analog’, the mission saw 200 scientists from 25 countries working together on different experiments and operational simulations across four continents and reporting back to the mission control base in Austria.

The ADAMA mission organised by ICEE.space, which Dr Pulvirenti was part of, was the first time a soft robotic exosuit had been integrated into a spacesuit, and the first field test of its kind. The experiments evaluated comfort, mobility and biomechanical effects when performing planetary surface tasks such as walking, climbing and load-carrying on loose terrain.

Dr Pulvirenti handmade the exosuit himself, teaching himself to sew as part of the process. “Fortunately my grandmother worked as a tailor and she was able to give me some advice,” Dr Pulvirenti said. He developed the lightweight exosuit alongside Vivo Hub colleagues at the University of Bristol.

The artificial muscles in the suit consist of two layers: an outer nylon layer and an inner thermoplastic layer that allows airtight inflation. The anchoring components, such as the waistband and knee straps, are made from Kevlar for high strength and tension resistance.

Dr Pulvirenti said: “The hope is that this technology could pave the way for future wearable robotic systems that enhance astronaut performance and reduce fatigue during extra-vehicular surface activities.

“I would love to continue developing this technology so that it could eventually be tested at the International Space Station.”

Dr Pulvirenti explained: “It's exciting that this technology could also potentially benefit people too. This exosuit is assistive, meaning it artificially boosts the lower-limb muscles, but we have also separately developed a resistive exosuit, which applies load to the body to help maintain muscle mass.

“Our next goal is to create a hybrid suit that can switch between assistance and resistance modes as needed, which could be of great benefit for people in need of support with mobility going through physical rehabilitation.”

ENDS

For further information or to arrange an interview with Dr Emanuele Pulvirenti, please contact Steve Salter, email steve.salter@bristol.ac.uk, mobile +44 (0)7964 022596 in the University of Bristol News and Content team, or email press-office@bristol.ac.uk.

Journal

Advanced Science

Article Title

A Resistive Soft Robotic Exosuit for Dynamic Body Loading in Hypogravity

The exosuit is being worn underneath the astronaut's spacesuit during the ADAMA simulation mission in Adelaide

Credit

Dr Emanuele Pulvirenti

Taft Armandroff and Brian Schmidt elected to lead Giant Magellan Telescope Board of Directors

New leadership appointed to guide the next phase of construction as Dr. Walter Massey concludes nearly a decade of service as chair of the GMTO Corporation Board of Directors

GMTO Corporation

image:

The Giant Magellan Telescope Board of Directors has elected Dr. Taft Armandroff as chair and Dr. Brian Schmidt as vice chair — guiding the observatory through its next phase of construction. We honor Dr. Walter Massey for nearly a decade of visionary leadership that helped shape the telescope’s foundation and global collaboration.

view moreCredit: GMTO Corporation

PASADENA, CA — November 4, 2025 — The GMTO Corporation, the 501(c)(3) nonprofit and international consortium building the Giant Magellan Telescope, today announced a leadership transition on its Board of Directors. After nearly a decade of leadership as chair, Dr. Walter Massey is retiring. The board has elected Dr. Taft Armandroff as its new chair and Nobel Laureate Dr. Brian Schmidt as vice chair.

Dr. Massey’s tenure guided the Giant Magellan Telescope through key design and construction milestones, helped secure nearly $500 million in private and public funding, and expanded the international consortium from 11 to 16 members. A physicist, educator, and national science leader, Dr. Massey has held transformative roles including director of the National Science Foundation, director of Argonne National Laboratory, president of Morehouse College and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and member of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. He has also served on the boards of BP, the Rand Corporation, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and was chairman of Bank of America. Dr. Massey will remain actively involved in the observatory’s success as special advisor to the GMTO Corporation, and his legacy will be celebrated by leaders in science, art, education, philanthropy, and government at the inaugural Giant Magellan Gala in November at the Adler Planetarium.

“It has been an honor guiding the Giant Magellan Telescope through this defining chapter,” said Dr. Massey. “This next generation observatory stands at the intersection of global collaboration and curiosity. I’m deeply proud of what we’ve achieved together, and I look forward to seeing the telescope reach first light under Taft’s leadership.”

Dr. Armandroff is a distinguished leader in astronomy, observatory operations, and instrumentation. He currently serves as director of the McDonald Observatory and professor of astronomy at The University of Texas at Austin, holding the Frank and Susan Bash Endowed Chair. Prior to UT Austin, he served as observatory director at the W.M. Keck Observatory and associate director of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (now known as NOIRLab). He has been recognized with prestigious honors, including the Distinguished Alumnus Award at Wesleyan University, the AURA Science Award, and the Dirk Brouwer Prize at Yale.

Dr. Armandroff’s research focuses on dwarf spheroidal galaxies, globular clusters, and stellar populations in the Milky Way and nearby galaxies. As a long-serving board member and former vice chair of the GMTO Corporation Board of Directors since 2016, he has played a central role in guiding strategic initiatives behind the Giant Magellan Telescope.

“Walter’s leadership over the last decade has been truly inspiring,” said Dr. Armandroff. “He built a strong foundation for one of the most ambitious scientific instruments ever conceived. I am deeply grateful to our international consortium for entrusting me with this role and look forward to working together to bring the Giant Magellan Telescope to life.”

As vice chair, Dr. Brian Schmidt brings extensive international scientific leadership to the Giant Magellan Telescope. A Nobel Laureate in Physics for his groundbreaking work on the accelerating expansion of the Universe, he is a distinguished professor of astronomy at the Australian National University and served as vice chancellor and president of ANU, where he advanced major research initiatives and international collaborations. Dr. Schmidt is widely recognized for his leadership in large-scale astronomy projects, public engagement in science, and advocacy for global scientific partnerships. He is also a recipient of the Shaw Prize, Gruber Prize, and Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics.

“The Giant Magellan Telescope shows what the international astronomy community can accomplish together,” Dr. Schmidt said. “I am honored to work alongside Taft and the GMTO Corporation Board of Directors as we take the next step toward a new era of discovery that will transform our understanding of the Universe.”

With this leadership transition, the board reaffirms its commitment to completing the next phase of construction — with more than 40% of the project already underway — advancing toward a successful National Science Foundation Final Design Review and continuing to secure the private and public funding needed to bring the observatory to completion in the 2030s.

Scientists recreate cosmic “fireballs” to probe mystery of missing gamma rays

University of Oxford

image:

The Fireball experiment installed in the HiRadMat irradiation area. Credit: Gianluca Gregori.

view moreCredit: Gianluca Gregori.

An international team of scientists, led by the University of Oxford, has achieved a world-first by creating plasma "fireballs" using the Super Proton Synchrotron accelerator at CERN, Geneva, to study the stability of plasma jets emanating from blazars. The results, published today (3 November) in PNAS, could shed new light on a long-standing mystery about the Universe’s hidden magnetic fields and missing gamma rays.

Blazars are active galaxies powered by supermassive black holes that launch narrow, near-light-speed beams of particles and radiation towards Earth. These jets produce intense gamma-ray emission extending up to several teraelectronvolts (1 TeV = 1012/a trillion eV), which is detected by ground-based telescopes. As these TeV gamma rays propagate across intergalactic space, they scatter off the dim background light from stars, creating cascades of electron–positron pairs. The pairs should then scatter on the cosmic microwave background to generate lower-energy (GeV = 10⁹ eV) gamma rays - yet these have not been captured by gamma-ray space telescopes, such as the Fermi satellite. Up to now, the reason for this has been a mystery.

One explanation is that the pairs are deflected by weak intergalactic magnetic fields, steering the lower-energy gamma rays away from our line of sight. Another hypothesis, originating from plasma physics, is that the pair beams themselves become unstable as they traverse the sparse matter that lies between galaxies. In this case, small fluctuations in the beam drive currents that generate magnetic fields, reinforcing the instability and potentially dissipating the beam’s energy.

To test these theories, the research team – a collaboration between the University of Oxford and the Science and Technology Facilities Council’s (STFC) Central Laser Facility (CLF)- used CERN’s HiRadMat (High-Radiation to Materials) facility to generate electron–positron pairs with the Super Proton Synchrotron and send them through a metre-long ambient plasma. This created a scaled laboratory analogue of a blazar-driven pair cascade propagating through intergalactic plasma. By measuring the beam profile and associated magnetic-field signatures, the researchers directly examined whether beam-plasma instabilities could disrupt the jet.

The results were striking. Contrary to expectations, the pair beam remained narrow and nearly parallel, with minimal disruption or self-generated magnetic fields. When extrapolated to astrophysical scales, this implies that beam-plasma instabilities are too weak to explain the missing GeV gamma rays — supporting the hypothesis that the intergalactic medium contains a magnetic field that is likely to be a relic of the early Universe.

Lead researcher Professor Gianluca Gregori (Department of Physics, University of Oxford) said: “Our study demonstrates how laboratory experiments can help bridge the gap between theory and observation, enhancing our understanding of astrophysical objects from satellite and ground-based telescopes. It also highlights the importance of collaboration between experimental facilities around the world, especially in breaking new ground in accessing increasingly extreme physical regimes.”

The findings, however, bring up more questions. The early Universe is believed to have been extremely uniform and it is unclear how a magnetic field may have been seeded during this primordial phase. According to the researchers, the answer may involve new physics beyond the Standard Model. The hope is that upcoming facilities such as the Cherenkov Telescope Array Observatory (CTAO) will provide higher-resolution data to test these ideas further.

Co-investigator Professor Bob Bingham (STFC Central Laser Facility and the University of Strathclyde) said: “These experiments demonstrate how laboratory astrophysics can test theories of the high-energy Universe. By reproducing relativistic plasma conditions in the lab, we can measure processes that shape the evolution of cosmic jets and better understand the origin of magnetic fields in intergalactic space.”

Co-investigator Professor Subir Sarkar (Department of Physics, University of Oxford) said: “It was a lot of fun to be part of an innovative experiment like this that adds a novel dimension to the frontier research being done at CERN – hopefully our striking result will arouse interest in the plasma (astro)physics community to the possibilities for probing fundamental cosmic questions in a terrestrial high energy physics laboratory.”

This collaborative effort involved researchers from the University of Oxford, STFC’s Central Laser Facility (RAL), CERN, the University of Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics, AWE Aldermaston, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics, the University of Iceland, and Instituto Superior Técnico in Lisbon.

Notes to editors:

For media enquiries and interview requests, contact Caroline Wood: caroline.wood@admin.ox.ac.uk

The study ‘Suppression of pair beam instabilities in a laboratory analogue of blazar pair cascades’ will be published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) at 20:00 GMT / 15:00 ET on Monday 3 November 2025 (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2513365122). To view an advance copy of the study under embargo, contact Caroline Wood: caroline.wood@admin.ox.ac.uk

About the University of Oxford

Oxford University has been placed number 1 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for the tenth year running, and number 3 in the QS World Rankings 2024. At the heart of this success are the twin-pillars of our ground-breaking research and innovation and our distinctive educational offer.

Oxford is world-famous for research and teaching excellence and home to some of the most talented people from across the globe. Our work helps the lives of millions, solving real-world problems through a huge network of partnerships and collaborations. The breadth and interdisciplinary nature of our research alongside our personalised approach to teaching sparks imaginative and inventive insights and solutions.

Through its research commercialisation arm, Oxford University Innovation, Oxford is the highest university patent filer in the UK and is ranked first in the UK for university spinouts, having created more than 300 new companies since 1988. Over a third of these companies have been created in the past five years. The university is a catalyst for prosperity in Oxfordshire and the United Kingdom, contributing around £16.9 billion to the UK economy in 2021/22, and supports more than 90,400 full time jobs.

Simulation of an initially uniform beam of electrons & positrons interacting with a plasma. As the beam travels through the background plasma, the positrons (red) become focused while the electrons (blue) spread out to form a surrounding cloud. This illustrates the physics behind ‘current filamentation instability’, which is believed to play a key role in the propagation and dynamics of cosmic jets. The simulation was performed with the OSIRIS Particle-in-Cell code and is among the largest ever carried out for such beam-plasma interactions.

Image credit: Pablo J. Bilbao & Luís O. Silva (GoLP, Instituto Superior Tecnico, Lisbon & University of Oxford).

The team in the CERN Control Centre operating the Fireball experiment.

Credit: Subir Sarkar.

Journal

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Article Title

Suppression of pair beam instabilities in a laboratory analogue of blazar pair cascades

Article Publication Date

7-Nov-2025

Laser links to bolster the next generation of satellite mega-constellations

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research provides $2M to help satellites in orbit distribute critical resources with laser light

University of Michigan

Lab photos and a graphic showing two satellite maneuvers

Large-scale satellite constellations, such as Starlink and Kuiper, exchange information at incredible speed through new laser-interlink technologies, but each satellite is an island in terms of power and propulsion.

A new effort led by the University of Michigan and funded with $2 million from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research aims to change that by harnessing those interlinks for power and momentum transfer as well.

Satellite constellations have transformed our ability to communicate across the globe while also advancing navigation and Earth observation, needed for applications like weather forecasting, wildfire tracking and disaster recovery. They operate as teams to gather and relay information, but each carries its own fuel and propulsion system to stay positioned correctly, in the right orbit and facing the right direction.

Sharing momentum with laser light could enable satellites to move without the burden and limitations of onboard fuel, while sharing energy can be used to enhance the efficiency of existing propulsion systems. Integrating these new operating modes with existing data transfer technology is the aim of the three-year project, called Orbital Architectures for Cooperative Laser Energetics, or ORACLE.

"With the explosive growth of satellite constellations, we are now at a moment where expanding cooperation between satellites via laser links can create capabilities we’ve never seen before. By integrating data, power and momentum sharing into a single laser-based framework, ORACLE could transform constellations from collections of independent satellites into dynamic, interconnected systems," said Christopher Limbach, U-M assistant professor of aerospace engineering, who leads the new project.

These new capabilities will improve the sustainability and lifetimes of space missions and make them more resilient to disruptions such as space weather. They will also make satellite constellations easier to reconfigure and facilitate the repositioning or removal of space debris.

The team is attacking the problem on four fronts:

Next-generation materials that allow satellites to efficiently convert laser beams into usable power while also serving as communication channels or solar power converters. This area is led by Seth Hubbard, an expert in designing and fabricating advanced photovoltaic materials and head of physics and astronomy at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Techniques that enable multiple laser beam bounces between satellites, amplifying the thrust provided by light for propellant-free maneuvering. This research thrust is led by Limbach, who brings expertise in how lasers may be used for space propulsion and power.

Advanced control and stabilization algorithms to maintain precise laser links despite unpredictable space environments. Dennis Bernstein, a leader in control theory and vibration suppression and the James E. Knott Professor of Aerospace Engineering at U-M, heads this effort.

Constellation-level decision frameworks that allow thousands of satellites to cooperate, redistribute resources and execute maneuvers on an unprecedented scale. This effort is led by Giusy Falcone, U-M expert in astrodynamics and autonomous decision-making and assistant professor of aerospace engineering.

In the final year of the project, the team members will integrate their technologies to create the first demonstration of a laser terminal capable of data, power and momentum transfer.

Chemists find clues to the origins of buckyballs in space

Far from Earth, in the vast expanses of space between stars, exists a treasure trove of carbon. There, in what scientists call the “interstellar medium,” you can find a wide range of organic molecules—from honeycomblike polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) to spheres of carbon shaped like soccer balls.

In a new study, an international team of researchers led by scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder have used experiments on Earth to recreate the chemistry deep in space. The group’s results may have uncovered key steps in the processes that shape these organic molecules over time.

The findings could reveal information about the building blocks that once formed Earth’s solar system, said Jordy Bouwman, lead author of the study. Billions of years ago, similar clouds of matter have condensed to form the seeds of what would become our own sun and its planets.

“We’re all made of carbon, so it’s really important to know how carbon in the universe gets transformed on its way to being incorporated in a planetary system like our own solar system,” said Bouwman, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry and scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder.

The research, published recently in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, sheds light on the formation of a class of molecules called fullerenes.

Fullerenes are made up of carbon atoms organized in the shape of a closed cage. The most famous example is buckminsterfullerene, or the buckyball, which gets its name from famed futurist Richard Buckminster Fuller. These molecules include 60 carbon atoms in the shape of a sphere and bear a striking resemblance to a FIFA regulation soccer ball.

Fullerenes, including buckyballs, float freely in the interstellar medium. But scientists have long struggled to explain where they come from and how they are formed.

The new study suggests that radiation in space may help to transform PAHs into fullerenes.

“This gives us a hint that the buckyballs that we find in space may be connected to these large aromatic molecules that are also abundant,” Bouwman said.

Space chemistry, on Earth

The group simulated the chemistry in space by studying two small PAH molecules called anthracene and phenanthrene.

PAHs are made up of carbon atoms arranged in a series of hexagons, not unlike a honeycomb. They’re abundant on Earth where you can find them in smoke, soot and other charred materials.

“If you put your steak on the grill for too long, and it gets black, that contains PAHs,” Bouwman said. “They’re a nasty byproduct of combustion.”

First, the researchers bombarded the two PAHs with a beam of electrons. It’s similar to what happens when radiation in space interacts with molecules in the interstellar medium.

This bombardment transformed the PAHs into new, charged organic molecules. The researchers then fed the products into an ion trap apparatus at a scientific facility called the Free Electron Lasers for Infrared eXperiments (FELIX). This one-of-a-kind national research facility is located in Nijmegen in the Netherlands and includes several lasers that spread across a large basement room. Using those lasers, the researchers were able to precisely probe the structure of their new molecules.

They were surprised when they saw the results.

Making buckyballs

Bouwman explained that when the team hit anthracene and phenanthrene with electrons, the molecules lost one or two of their hydrogen atoms.

In the process, they also radically changed their structures, like disassembling a Lego castle and building a new structure. Instead of just including hexagons, the resulting products now carried carbon atoms arranged in the shape of both hexagons and pentagons.

That radical reaction had never been seen before, Bouwman said. Whether these kinds of pentagon-bearing molecules are also common in space isn’t clear.

“That was a very surprising result—that just by kicking off a hydrogen atom or two, the entire molecule completely rearranged,” said Sandra Brünken, a co-author of the study, associate professor at Radboud University and group leader at FELIX.

The results were eye-opening, in part because those kinds of molecules are also really easy to fold up. (Just picture a soccer ball, which is made up of a mix of both hexagons and pentagons).

In other words, these pentagon-bearing molecules may be the missing link for converting common PAHs into buckyballs and other fullerenes.

Bouwman and Brünken hope that astrophysicists will take note. Scientists could use the team’s findings to see if similar pentagon-bearing molecules exist deep in space using tools like the James Webb Space Telescope—the most powerful telescope ever launched.

“You can take our results from the laboratory, and then use them as a fingerprint to look for the same signatures in space,” Brünken said.

CU Boulder co-authors of the new study include LASP graduate students Madison Patch and Rory McClish. Other co-authors include scientists at Radboud University; Leiden University in the Netherlands; Paris-East Créteil University in France; and the University of Maryland College Park.

Journal

Journal of the American Chemical Society

DOI

Dark matter does not defy gravity

A team led by UNIGE shows that the most mysterious component of our Universe obeys the laws of classical physics. But doubts remain.

Université de Genève

Does dark matter follow the same laws as ordinary matter? The mystery of this invisible and hypothetical component of our Universe — which neither emits nor reflects light — remains unsolved. A team involving members from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) set out to determine whether, on a cosmological scale, this matter behaves like ordinary matter or whether other forces come into play. Their findings, published in Nature Communications, suggest a similar behaviour, while leaving open the possibility of an as-yet-unknown interaction. This breakthrough sheds a little more light on the properties of this elusive matter, which is five times more abundant than ordinary matter.

Ordinary matter obeys four well-identified forces: gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak forces at the atomic level. But what about dark matter? Invisible and elusive, it could be subject to the same laws or governed by a fifth, as yet unknown force.

To unravel this mystery, a team led by UNIGE set out to determine whether, on a cosmic scale, dark matter falls into gravitational wells in the same way as ordinary matter. Under the influence of massive celestial bodies, the space occupied by our Universe is distorted, creating wells. Ordinary matter — planets, stars and galaxies — falls into these wells according to well-established physical laws, including Einstein's theory of general relativity and Euler's equations. But what about dark matter?

“To answer this question, we compared the velocities of galaxies across the Universe with the depth of gravitational wells,” explains Camille Bonvin, associate professor in the Department of Theoretical Physics at UNIGE’s Faculty of Science and co-author of the study. “If dark matter is not subject to a fifth force, then galaxies — which are mostly made of dark matter — will fall into these wells like ordinary matter, governed solely by gravity. On the other hand, if a fifth force acts on dark matter, it will influence the motion of galaxies, which would then fall into the wells differently. By comparing the depth of the wells with the galaxies’ velocities, we can therefore test for the presence of such a force.”

Euler's equations still valid

Applying this approach to current cosmological data, the research team concluded that dark matter falls into gravitational wells in the same way as ordinary matter, thus obeying Euler's equations. “At this stage, however, these conclusions do not yet rule out the presence of an unknown force. But if such a fifth force exists, it cannot exceed 7% of the strength of gravity — otherwise it would already have appeared in our analyses,” says Nastassia Grimm first author of the study and former postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Theoretical Physics at UNIGE’s Faculty of Science who has recently joined the Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation at the University of Portsmouth.

These initial results mark a major step forward in characterising dark matter. The next challenge will be to determine whether a fifth force governs it. “Upcoming data from the newest experiments, such as LSST and DESI, will be sensitive to forces as weak as 2% of gravity. They should therefore allow us to learn even more about the behaviour of dark matter, concludes Isaac Tutusaus, researcher at ICE-CSIC and IEEC and associate professor at IRAP, Midi-Pyrénées observatory, University of Toulouse, co-author of the study.

Journal

Nature Communications

Method of Research

News article

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Does dark matter fall in the same way as standard model particles? A direct constraint of Euler's equation with cosmological data

Article Publication Date

3-Nov-2025

Why The US Leads In Military Innovation: The Case Of X-37B – Analysis

File photo of the U.S. Space Force's X-37B space plane is seen shortly after landing at NASA's Kennedy Space Center on Nov. 12, 2022, bringing an end to its OTV-6 mission. (Image credit: Boeing/US Space Force)

November 4, 2025

By Observer Research Foundation

By Prateek Tripathi

Technological innovation has always been the primary yardstick in assessing a nation’s military capabilities. It explains why new technologies are often developed through military research before spilling over to societal applications.

The United States (US) Space Force’s X37-B programme provides a shining example of how this dynamic plays out. From testing novel space manoeuvres in the past to now experimenting with quantum inertial navigation systems, X37-B exemplifies why the US has been a pioneer in future technologies and serves as an indicative case study for India on how to hone and develop future military capabilities in an increasingly complex neighbourhood environment.

A Background of the X-37B Programme

Based on NASA’s X-37 programme (1999-2004), the X-37B was built by Boeing, which describes it as “an uncrewed, autonomous spaceplane designed for advanced experimentation and technology testing.” Though initially operated solely by the Department of the Air Force Rapid Capabilities Office (DAF RCO) since 2010, it is now jointly run by the DAF RCO and the US Space Force’s Delta 9 unit, which is responsible for orbital warfare. Starting from 2010, the X-37B programme had launched seven orbital test vehicles (OTVs) till March 2025.

Figure 1: X-37B OTVs. Source: Secure World Foundation

Figure 1: X-37B OTVs. Source: Secure World FoundationThroughout its history, the initiative has served as a testbed for several novel and innovative technologies. OTV-4’s payload included a Hall-Effect thruster for experimentation, which was subsequently integrated into the Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) military satellite communication programme. It also carried about 100 different types of materials for testing in a space environment as part of NASA’s Materials Exposure and Technology Innovation in Space (METIS) programme. OTV-5 included a payload to test experimental electronics and heat pipe technologies in a long-duration space environment lasting 780 days. Furthermore, OTV-6 also tested an on-orbit power beaming system, a novel technology which collects solar power and subsequently converts it into a microwave beam.

OTV-7 broke new ground in testing new orbital regimes as it was the first X-37B mission to operate in a Highly Eccentric Orbit (HEO) instead of a Low Earth Orbit (LEO). It further tested novel aerobraking manoeuvres, which essentially utilise Earth’s atmospheric drag to transition between different orbital regimes in contrast to burning fuel. Consequently, OTV-7 could have significant implications for enhancing space domain awareness in the future.

New Technologies Being Tested Aboard X-37B OTV-8

The X-37B OTV-8 was launched on 21 August 21 2025, from the Kennedy Space Centre, utilising SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. One of the pivotal technologies being tested by OTV-8 is a quantum inertial sensor, built by a startup called Vector Atomic, under contract from the Pentagon’s Defence Innovation Unit (DIU). This could be particularly important for future military and space capabilities, considering quantum sensing holds enormous potential for supplementing or even eventually replacing current positioning, timing, and navigation (PNT) systems, which are heavily reliant on the Global Positioning System (GPS). Given the increasing instances of GPS-jamming and spoofing in recent conflicts, quantum sensing-based PNT systems could be instrumental in GPS-denied environments.

Another critical technology being tested by the flight is space-based laser communication for both satellite-to-satellite and satellite-to-ground communication, which are currently based on radio-frequency data links. Laser-based links can allow more secure communication in the future while simultaneously enhancing bandwidth and data-carrying capacity. This likely ties in with the Space Development Agency and DIU’s future initiatives, which aim to set up satellite constellations based on “hack-proof” optical communication.

Though there is also some speculation regarding orbital warfare testing aboard the OTV-8, particularly due to Delta 9’s oversight, this has not been officially confirmed.

Lessons for Indian Defence R&D

While the quantitative aspects of a sophisticated programme such as X-37B can be analysed ad infinitum, some qualitative takeaways do stand out, and can aid significantly if incorporated into India’s long-term military research strategy:Identifying Unexplored Domains and Acting Pre-emptively

The X-37B programme was ahead of its time, and recognised the importance of enhanced space capabilities and domain awareness at a time when it was not considered feasible or particularly relevant. Even the majority of the current discussion on space capabilities is centred around LEO satellites, whereas X-37B focuses on spacecraft with enhanced orbital manoeuvrability in HEO, the apogee of which can extend to 35,000 km compared to 2,000 km in the case of LEO. The example set by the visionary nature of the initiative has inspired China to pursue a similar programme, Shenlong, which completed its third test flight in September 2024, performing proximity manoeuvres not too dissimilar from the X-37B OTVs.

However, novel ideas also involve taking significant risks, necessitating specific government-backed funding mechanisms for exploring new and unexplored domains, as well as the willingness to pursue them. This, in turn, requires developing a culture for innovation.Civil-Military Fusion

While there is much deliberation over the doctrine of civil-military fusion, the X37-B programme has successfully implemented it on a practical basis. It serves as a worthwhile case study on how government, military, private sector, and academia can cooperate effectively, synergising individual strengths to develop novel military technologies, which is indispensable in solidifying foundational military research and development (R&D). This is evident in the active involvement of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), DAF RCO, Space Force, DIU, Boeing, SpaceX, Vector Atomic, and other diverse stakeholders. On the academic front, OTV-6 deployed an experimental satellite called FalconSAT-8, developed by USAF academy students. Harmonising and coordinating such a wide variety of stakeholders is an arduous, though necessary, prerequisite for achieving civil-military fusion.Enabling Technology Intersection

The X37-B initiative recognised the importance of space-based experimentation in enhancing terrestrial and naval capabilities by serving as testbeds for other emerging technologies, such as quantum sensing and laser-based optical communication. Recognising and pursuing the intersection of novel technologies is critical in providing the all-important competitive edge to any nation’s military capabilities.Strategic Communication and Outreach

On the whole, the US military establishment has been quite reluctant to share details throughout the programme’s history, with outreach being largely limited to achieving power projection based on prevailing geopolitical circumstances, while inhibiting the disclosure of the majority of the disruptive and offensive capabilities of the spacecraft. India needs to be similarly discreet regarding its military capabilities and research. It should divulge only necessary details to maintain this status quo.The Need for an Integrated Space Command

Although India has initiated multiple steps towards developing a dedicated space command, it still suffers from several inadequacies, largely stemming from a general lack of military involvement within the Indian Space Commission. Up until now, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has played a leading role in space research. However, it must be noted that despite its pioneering research and initiatives in the field, it is primarily a civilian organisation, not a military one. India’s over-reliance on ISRO has been detrimental to furthering its military ambitions in the space domain. For instance, while ISRO has tested autonomous spacecraft such as the Reusable Launch Vehicle Autonomous Landing Mission (RLV LEX), its capabilities are limited in comparison to its peers in the absence of military involvement and oversight. With the future of warfare gradually tilting towards the space domain, this situation needs to be rectified as soon as possible. The circumstances necessitate the establishment of an integrated Indian military space command, similar to the US Space Force, which would enable focused military R&D in the space domain as well as streamlined coordination with scientific organisations like ISRO and the country’s growing space startup ecosystem.

Conclusion: The Success of Make in India Hinges on Innovation

Despite recent political and economic upheavals, the US has served as the dominant global military power since the post-World War II era. This has been largely due to its culture of developing innovative technologies, as exemplified by the X-37B initiative. To achieve its ambitious goal of “Make in India” in the defence sector, India must lead with military research and development (R&D). By analysing the precedents set by the United States in this area, identifying relevant case studies, and incorporating suitable elements into its military strategy promptly, India can make significant progress toward this objective. China’s growing military and space capabilities through initiatives such as Shenlong, coupled with its willingness to supply these technologies to Pakistan as witnessed during Operation Sindoor, should impart a further sense of urgency to the cause.

Source: This article was published by the Observer Research Foundation.

Observer Research Foundation

ORF was established on 5 September 1990 as a private, not for profit, ’think tank’ to influence public policy formulation. The Foundation brought together, for the first time, leading Indian economists and policymakers to present An Agenda for Economic Reforms in India. The idea was to help develop a consensus in favour of economic reforms.

No comments:

Post a Comment