Do you really want a man in his sixties running the country?

Neal Umphred

May 16, 2019 ·

https://medium.com/tell-it-like-it-was/wild-in-the-streets-as-prescient-sociopolitical-satire-730a2fa7d561

Max Frost doing a benefit concert in the 1968 American International Pictures’

movie Wild in the Streets. (Photo: personal collection)

JACK WEINBERG DEFINED THE SIXTIES: In November 1964, he did an interview for The San Francisco Chronicle about the Free Speech Movement. According to Weinberg, the reporter was making him angry with his line of inquiry: “It seemed to me his questions were implying that we were being directed behind the scenes by Communists or some other sinister group. I told him we had a saying in the movement that we don’t trust anybody over 30. It was a way of telling the guy to back off, that nobody was pulling our strings.”

The phrase “We don’t trust anybody over 30” was an overnight sensation. (In modern parlance, it went viral.)

That was 1964 and there is a good chance that he knew exactly the kind of effect that it would have on young people around the country (although he denies it). He might not have had a clue that it would also have an effect on non-political movers and shakers in Hollywood with a bent for sociopolitical satire. At least one movie seems to have used those six words as the basis for its plot — Wild in the Streets.

Black humor is a sub-genre of comedy in which laughter arises from cynicism.

This article is a follow-up to “The Return Of Max Frost & The Troopers” (2014) and looks at American International Pictures’ Wild in the Streets. For this article, I pulled a DVD from the library and watched it for the first time in more than twenty years.

I review the sociopolitical aspects of the script forty years later and ask a few questions. I found some real accuracy and some possible prescience along with a lot of nonsense.

The plot revolves around a hip, young, flippant pop star being elected President of the United States and turning the country’s political and social conventions on their head. The movie’s script was based on the short story “The Day It All Happened, Baby!” by Robert Thom, originally published in the December 1966 issue of Esquire magazine. Thom expanded the story to a movie script.

JACK WEINBERG DEFINED THE SIXTIES: In November 1964, he did an interview for The San Francisco Chronicle about the Free Speech Movement. According to Weinberg, the reporter was making him angry with his line of inquiry: “It seemed to me his questions were implying that we were being directed behind the scenes by Communists or some other sinister group. I told him we had a saying in the movement that we don’t trust anybody over 30. It was a way of telling the guy to back off, that nobody was pulling our strings.”

The phrase “We don’t trust anybody over 30” was an overnight sensation. (In modern parlance, it went viral.)

That was 1964 and there is a good chance that he knew exactly the kind of effect that it would have on young people around the country (although he denies it). He might not have had a clue that it would also have an effect on non-political movers and shakers in Hollywood with a bent for sociopolitical satire. At least one movie seems to have used those six words as the basis for its plot — Wild in the Streets.

Black humor is a sub-genre of comedy in which laughter arises from cynicism.

This article is a follow-up to “The Return Of Max Frost & The Troopers” (2014) and looks at American International Pictures’ Wild in the Streets. For this article, I pulled a DVD from the library and watched it for the first time in more than twenty years.

I review the sociopolitical aspects of the script forty years later and ask a few questions. I found some real accuracy and some possible prescience along with a lot of nonsense.

The plot revolves around a hip, young, flippant pop star being elected President of the United States and turning the country’s political and social conventions on their head. The movie’s script was based on the short story “The Day It All Happened, Baby!” by Robert Thom, originally published in the December 1966 issue of Esquire magazine. Thom expanded the story to a movie script.

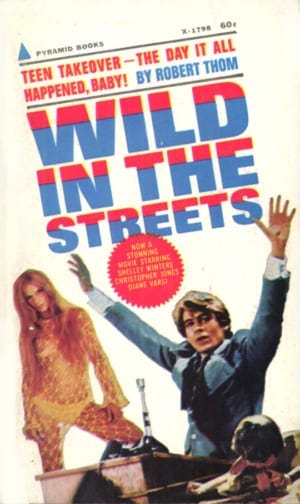

Robert Thom eventually expanded his movie script into a novel version of Wild in the Streets, which was published as a tie-in with the movie as a paperback original. This is the US edition from Pyramid Books. (Photo: personal collection)

A b-movie as sociopolitical satire

When I picked up Wild in the Streets from the library, I assumed that my reaction would be one of dismissal: it was just another B-movie with an absurd plot intended to get teenagers to part with their allowances.

My actual reaction was different: I was impressed by the basic intelligence of the script and its politically and socially savvy observations and its humor, which ranged from sophomoric to ironic to dark.

Sure, it’s a B-movie, so the acting of star Christopher Jones as Max Frost (formerly Max Flatow) and his acolytes/band members is less than stellar, and Shelley Winters as Max’s mother Mrs. Flatow is so over-the-top as to be beyond caricature. But they are ably supported by co-star Hal Holbrook and the rest of the cast, notably veterans Ed Begley, Millie Perkins, and Kevin Coughlin.

Wild in the Streets attracted several cameo appearances by such non-actor celebrities as entertainment columnist Army Archerd, attorney Melvin Belli, author Pamela Mason, and journalist Walter Winchell. Record industry mover-and-shaker Dick Clark plays a radio broadcaster.

The movie featured guest appearances by Dick Clark, Billy Mumy, Bobby Sherman, Peter Tork, and Barry Williams.

There were also some fresh faces making early appearances: the teenaged Max was played by Barry Williams years before anyone had conceived of The Brady Bunch. An uncredited Bobby Sherman plays a journalist who briefly interviews President Frost. Bill Mumy appears as an unidentified child.

Monkee Peter Tork is part of a crowd scene when he bumps up against Shelley Winters at a stage entrance as the onlookers chant, “We want Max!” And the film marked the screen début of Richard Pryor.

A b-movie as sociopolitical satire

When I picked up Wild in the Streets from the library, I assumed that my reaction would be one of dismissal: it was just another B-movie with an absurd plot intended to get teenagers to part with their allowances.

My actual reaction was different: I was impressed by the basic intelligence of the script and its politically and socially savvy observations and its humor, which ranged from sophomoric to ironic to dark.

Sure, it’s a B-movie, so the acting of star Christopher Jones as Max Frost (formerly Max Flatow) and his acolytes/band members is less than stellar, and Shelley Winters as Max’s mother Mrs. Flatow is so over-the-top as to be beyond caricature. But they are ably supported by co-star Hal Holbrook and the rest of the cast, notably veterans Ed Begley, Millie Perkins, and Kevin Coughlin.

Wild in the Streets attracted several cameo appearances by such non-actor celebrities as entertainment columnist Army Archerd, attorney Melvin Belli, author Pamela Mason, and journalist Walter Winchell. Record industry mover-and-shaker Dick Clark plays a radio broadcaster.

The movie featured guest appearances by Dick Clark, Billy Mumy, Bobby Sherman, Peter Tork, and Barry Williams.

There were also some fresh faces making early appearances: the teenaged Max was played by Barry Williams years before anyone had conceived of The Brady Bunch. An uncredited Bobby Sherman plays a journalist who briefly interviews President Frost. Bill Mumy appears as an unidentified child.

Monkee Peter Tork is part of a crowd scene when he bumps up against Shelley Winters at a stage entrance as the onlookers chant, “We want Max!” And the film marked the screen début of Richard Pryor.

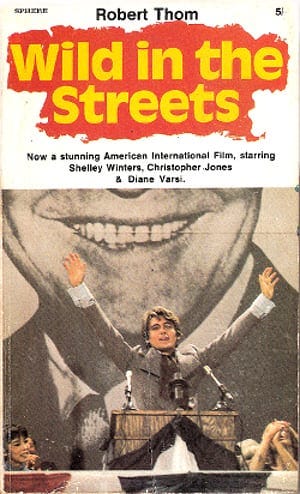

The UK edition from Sphere Books has a different cover, which I find much more effective than the Pyramid book form the US. (Photo: personal collection)

A b-movie with an absurd plot

Here is an outline of the movie’s plot:

A. Enormously popular rock star Max Frost is approached by Senator Johnny Fergus, who attempts to enlist him in getting the youth vote to support his Presidential bid.

B. Frost agrees to support Fergus if the Senator will get a bill passed to lower the voting age to 14.

C. The bill is passed and Frost turns the tables on Fergus and runs for President himself and is subsequently elected by the newly enfranchised voters.

D. President Frost enacts a series of laws that penalize those over the age of 35 and turns the country into a youth-oriented, somewhat “liberal” utopia.

E. Mayhem does not ensue.

That’s the movie in a nutshell. Casting and directing and production aside, it was the politics of the film that caught my attention forty-six years later. (Believe it or not, Wild in the Streets was nominated for an Academy Award for Film Editing but lost to the Steve McQueen vehicle Bullitt.)

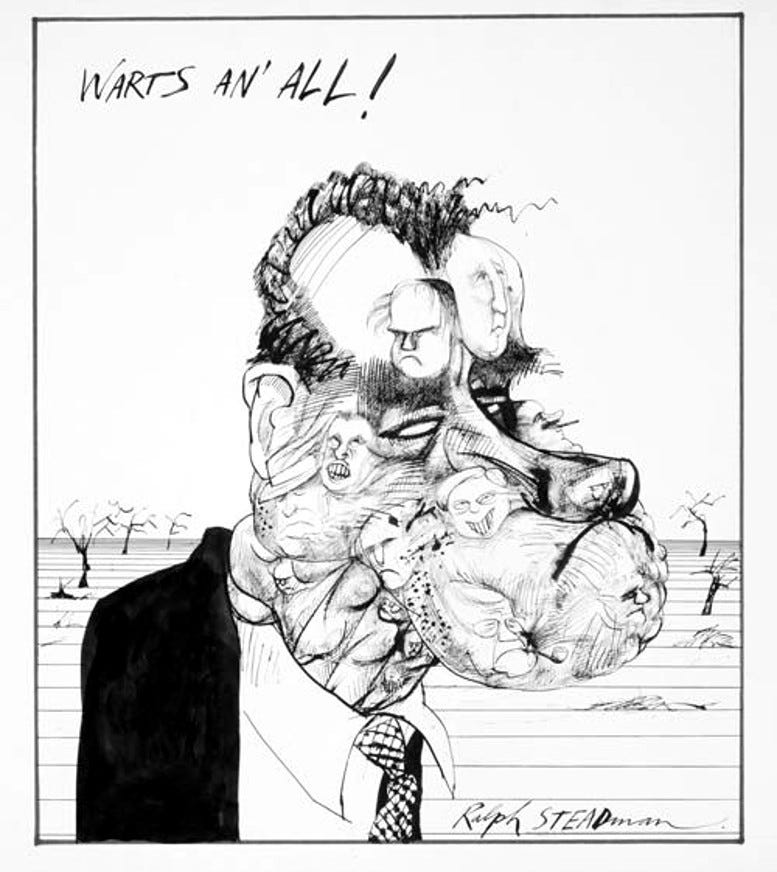

Ralph Steadman’s brutal caricature of Nixon, a politician considered unelectable at the time that Wild in the Streets was being made in 1967. Little did we know what the immediate future had in store for us. (Image: Ralph Steadman Art Collection)

Firing on demonstrators was unthinkable!

Wild in the Streets was somewhat prescient in 1968 in foreseeing that certain political and social movements would continue and even escalate. (Not an impossible act of foreseeing then.) For example, a peek into the near future is the big demonstration that occurs in Washington with a crowd of more than 3,000,000! In 1968, no political demonstration had reached much more than 100,000.

This would change with the Moratorium March on Washington on November 15, 1969, that drew more than 500,000 people to protest President Nixon’s bombing of Southeast Asia.

(Any oldsters reading this article whose consciousness and memory survived the era might recall that Tricky Dick had been elected in 1968 because he hinted at a “secret plan” to end the war. This plan included bombing Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand.)

Let the old world make believe it’s blind and deaf and dumb, but nothing can change the shape of things to come.

At the movie’s fictional demonstration, a television newsman notes the building intensity in the crowd and in the police and guardsmen: “The military and police are helpless unless directed to fire on the crowd — and that seems unthinkable.”

Now, cops beating black civil rights demonstrators in the South was nothing new in 1967–1968. But cops firing into a crowd of mostly white people was unheard of!

That would change: on May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard opened fire in concert and on orders on student demonstrators at an anti-war rally on the campus grounds of Kent State University. Four were murdered — but that’s another story.

(Wild in the Streets was produced well in advance of the police riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on August 28, 1968. There, police officers were witnessed, photographed, and filmed beating demonstrators, observers, and even members of the media!)

Rising up angry in the sky

After the newsman makes his “unthinkable” statement, individual police officers open fire with their handguns, killing several people. In a somewhat jarring juxtaposition, this scene of murder at the hands of those hired to “serve and protect” is followed by the movie’s musical high point, Max performing “Shape of Things to Come” with the following lyrics:

There’s a new sun rising up angry in the sky.

and there’s a new voice saying, “We’re not afraid to die!”

Let the old world make believe it’s blind and deaf and dumb,

but nothing can change the shape of things to come.

There are changes lying ahead in every road

and there are new thoughts ready and waiting to explode.

When tomorrow is today, the bells may toll for some,

but nothing can change the shape of things to come.

The future’s coming in now, sweet and strong.

Ain’t no one gonna hold it back for long.

There are new dreams crowding out old realities.

There’s revolution sweeping in like a fresh new breeze.

Let the old world make believe it’s blind and deaf and dumb,

but nothing can change the shape of things to come.

Firing on demonstrators was unthinkable!

Wild in the Streets was somewhat prescient in 1968 in foreseeing that certain political and social movements would continue and even escalate. (Not an impossible act of foreseeing then.) For example, a peek into the near future is the big demonstration that occurs in Washington with a crowd of more than 3,000,000! In 1968, no political demonstration had reached much more than 100,000.

This would change with the Moratorium March on Washington on November 15, 1969, that drew more than 500,000 people to protest President Nixon’s bombing of Southeast Asia.

(Any oldsters reading this article whose consciousness and memory survived the era might recall that Tricky Dick had been elected in 1968 because he hinted at a “secret plan” to end the war. This plan included bombing Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand.)

Let the old world make believe it’s blind and deaf and dumb, but nothing can change the shape of things to come.

At the movie’s fictional demonstration, a television newsman notes the building intensity in the crowd and in the police and guardsmen: “The military and police are helpless unless directed to fire on the crowd — and that seems unthinkable.”

Now, cops beating black civil rights demonstrators in the South was nothing new in 1967–1968. But cops firing into a crowd of mostly white people was unheard of!

That would change: on May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard opened fire in concert and on orders on student demonstrators at an anti-war rally on the campus grounds of Kent State University. Four were murdered — but that’s another story.

(Wild in the Streets was produced well in advance of the police riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on August 28, 1968. There, police officers were witnessed, photographed, and filmed beating demonstrators, observers, and even members of the media!)

Rising up angry in the sky

After the newsman makes his “unthinkable” statement, individual police officers open fire with their handguns, killing several people. In a somewhat jarring juxtaposition, this scene of murder at the hands of those hired to “serve and protect” is followed by the movie’s musical high point, Max performing “Shape of Things to Come” with the following lyrics:

There’s a new sun rising up angry in the sky.

and there’s a new voice saying, “We’re not afraid to die!”

Let the old world make believe it’s blind and deaf and dumb,

but nothing can change the shape of things to come.

There are changes lying ahead in every road

and there are new thoughts ready and waiting to explode.

When tomorrow is today, the bells may toll for some,

but nothing can change the shape of things to come.

The future’s coming in now, sweet and strong.

Ain’t no one gonna hold it back for long.

There are new dreams crowding out old realities.

There’s revolution sweeping in like a fresh new breeze.

Let the old world make believe it’s blind and deaf and dumb,

but nothing can change the shape of things to come.

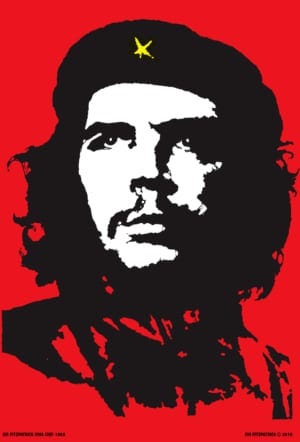

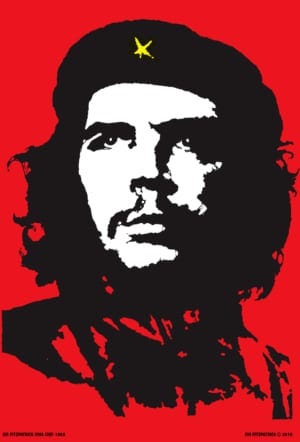

Jim Fitzpatrick’s portrait of Che Guevara from 1968 became one of the biggest selling posters of the era. (Image: Jim Fitzpatrick website)

We chose Che over James Dean

Throughout the movie, those teens that experience emancipation from their parents and their social strictures all act alike — like James Dean wannabes. And while posters of the ’50s teen idol appear on the walls of at least one kid’s room, few ‘militant’ teens in the US with any sense of militancy in the ’60s were enthralled by Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause image or any other such icon from the previous decade. You were far more likely to find posters of Che Guevara on the walls of politically hip kids.

Surprisingly — and I say that even fifty years after the movie was made — Senator Fergus drunkenly exclaims, “We pour napalm on our own men!” That is not so astounding a statement today: we also sprayed our own troops with Agent Orange and used experimental, mind-warping drugs on them. But it was all but sacrilege to say such a thing in 1968!

Certainly, no member of the military, the government, or the media acknowledged these horrors.

“Nixon would sure look dumb with long hair. Reagan would look worse!”

By the late ’60s, the counterculture was divided: one portion turned increasingly militant through its awareness of the real politics of America. The other all but turned its back on politics, real or otherwise, believing it a futile field in which to make any meaningful change. They adopted Timothy Leary’s slogan, “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” (Leary’s statement was a kind of call-to-arms, not the turn to the apathy that has prevailed in younger Americans ever since they were given the right to vote in 1972.)

One of Max’s underlings states that “We could raid the FBI,” a claim that was absurd in 1968 but is now a part of our recent past. Had personal computers existed then as they do now, hacking the secrets of the FBI, CIA, NSA, etc., would have probably been an ongoing occurrence.

Max’s Mom (Shelley Winters) toking up with a small water pipe in her hippie gear. (Photo: personal collection)

Turn on and tune in against your will

President Frost decides to dose the water supply of DC with LSD. When the acid-dosed Senate convenes, the behavior of the tripping Senators looks remarkably like the behavior of men just back from a 6-martini lunch. The movie’s attempt at giving the viewer an idea of the psychedelic effects being experienced is to simply put a monochromatic wash of color over the film. It is among the least convincing moments of psychedelia ever put to film, even for a B-movie. But you get the point.

Continually wanting to enjoy the good graces (and other benefits more tangible) of her son’s success, Max’s mother embraces the new generation, donning appropriate hippie garb, at least as Hollywood saw it. When we first see Shelley Winters in her ‘earth mother’ persona, I thought she looked like a Halloween costume manufacturer’s idea of a Mama Cass outfit!

She also undergoes LSD therapy!

It’s absurd and funny and scary and pathetic.

In France, the movie was given a new title: Les Troupes de la Colere (“The Troops of Anger”). The movie also was promoted with a very different image on the posters, playing up the music angle with a red, white, and blue guitar with the “power fist” at the top of the neck. (Image: Film Art Gallery)

A longhaired Rep*blican candidate

In one of the movie’s sillier uses of irony, Max Frost is pursued by the Rep*blican Party to run for President! Despite the distaste that he and his mates have for the GOP, they accept, if only because it cuts through the necessity of starting a political party from scratch.

While discussing the party, one band member remarks, “Nixon would sure look dumb with long hair. Ronald Reagan would look worse.”

This is both funny and another display of foresight: few took California Governor Reagan seriously as presidential timber in 1968. Even many Rep*blicans considered him a rightwing extremist at the time.

(I was just becoming politically aware in 1968. I was a junior in high school, turning 17 that year, and considering the possibility of being drafted even as a college student if the war got any crazier. I remember left-of-center comrades praying that the Rep*blicans were loony enough to nominate Reagan, as he was almost certainly unelectable in 1968. They believed that if he moved on his extremist positions in the ’60s, he would precipitate the revolution so many believed was coming eventually.

“Do you really want a man in his sixties running the country?”

Ten years later, the GOP had moved so far to the right that Reagan could be touted as a moderate, a candidate who could bridge the growing chasm between hardline conservatives and everyone else. Still a reactionary, the older Reagan was more inclined to use his Libertarian-leaning philosophies to assist the wealthy elite economically rather than punish the working class opposition politically.)

In a line that probably sums up the spirit of the movie better than any other, Max asks rhetorically, “Do you really want a man in his 60s running the country?”

While this was probably intended merely as satire, it is not a wholly unfounded question: few in American politics dare question the acceptance of age as indicative of responsibility and awareness. This despite the incompetent and despicable performances of many elected officials over the age of 50 throughout our history.

Once it is announced that Max Frost will be running as the Rep*blican candidate for President, his mother transitions from Earth Mother to Moral Majority Mother. In fact, Shelley Winters’ affectations and vocal mannerisms combined with her new apparel call to mind Margaret Thatcher, then waiting in the wings to take command of the British government and instigate a reign of austerity that nearly wrecked England’s economy.

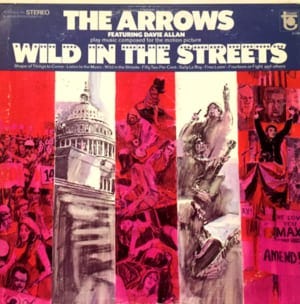

Not to miss out on a chance to sell a few records, Tower issued two albums titled Wild in the Streets. The album on top is the original soundtrack album features Davie Allan & the Arrows under various guises. The album below is Davie Allan playing new guitar licks to tracks recorded for the soundtrack album. (Photos: personal collection)

Echoes of MLK and RFK

In his first State of the Union address, President Frost is not as satirical as it probably seemed in 1968. That is until he announces his plan for Americans over the age of 30, which is when the humor darkens deeply.

By now, his former political mentor Senator Fergus realizes the monster that he has created and draws a gun on the Senate floor in a feeble attempt to assassinate the new Executive.

Here we get an echo of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy. These were both recent events and fresh wounds to moviegoers in late 1968 and early ’69 when the film was making the rounds of theaters and drive-ins.

When the President’s new plans are put into motion, citizens over the age of 35 are placed into “rehabilitation camps,” a term carefully coined to avoid using the Nazi’s concentration camps for Jews and other undesirables and the American relocation camps for Japanese origin during WWII.

In a subtly funny scene, the initial inmates are seen being shipped to Camp Paradise (ho ho) in what looks like a giant Volkswagen bus, the quintessential hippie vehicle!

The inmates are force-fed LSD on what I would assume to be a regular basis, just as any patient in a facility for the mentally ill is placed on a regular regimen of psychotropic drugs today. They are stripped of the clothing that marks their personality and forced to wear a unisex robe, depriving them of a smidgen of individuality and self-respect.

Scenes of the inhabitants of Camp Paradise in their park environment have the old folk singing childlike ditties and dancing ring-around-the-rosy. I assume this was a mockery of the often silly play that hippies were seen playing in Golden Gate Park, often while tripping. (These scenes would not be out of place as a depiction of the Eloi in George Pal’s movie version of H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine. Made in 1960, this was one of the best-produced and realized science fiction movies of the pre-Space Odyssey era.)

More dark humor: in the movie, Hawaii is the only state not to support Max in the election. Consequently, the island populace is punished by being given a “lethal overdose of STP.” Those Hawaiians who survive are left in a non-functioning state that I could easily associate with the term acid casualties, then being bandied about by trippers and non-trippers alike.

(STP was an extraordinarily powerful hallucinogen that provided a very short but a very intense trip. It caused many bummers and never caught on with the Leary Generation. Plus the concept of permanent brain damage due to LSD was disproven decades ago. But permanent emotional damage to those who were already emotionally fragile is another story.)

Extreme left as extreme right

In another of the film’s accurate sociopolitical observations on behavior, the young Americans that assume political power behave just like every other group with the same power! This includes a black-garbed (think ‘Nazi SS’) secret police for rounding up stray over 35-year old citizens who are simply trying to live outside the law and the restrictions of the dominant social beliefs and ethics of the mass culture (think ‘hippies’).

When this goon squad arrests Max’s mother, she attempts to resist arrest by claiming to be young. The squad leader then assails her with the best double-entendre of the movie: “You are the biggest mother of them all!”

In a later scene, Max drops off a young girl for babysitting and the child is dressed in black, calling forth memories of the Hitler Youth movement of the 1920s (der Hitlerjugend).

The Frost administration does have some redeeming features and positive goals, including the return of all troops stationed around the world, thus ending US imperialism, and feeding the hungry of the world with excess American grain, a plan that has been bandied about in real life for decades with little success. (Even if it does undercut the principles of American cutthroat capitalism.)

Political satire or black humor?

Referring back to this title and its reference to political and social satire and black comedy, let’s ask some questions:

Does Wild in the Streets work as satire? Yes, absolutely! While some of it was sophomoric even in 1968 and is even more dated in 2017, some satiric aspects of it have taken on whole new meanings in the years since its release.

Is Wild in the Streets a black comedy? The definition of a black comedy (or dark comedy) is “a comic work that employs black humor, which is humor that makes light of the otherwise serious subject. The term black humor was coined by Surrealist majordomo and theoretician André Breton in 1935 to designate a sub-genre of comedy and satire in which laughter arises from cynicism and skepticism, often relying on topics such as death.” Wild In The Streets certainly has elements of black humor and therefore aspects of a black comedy.

This is a poster for the 1980 presidential election between incumbent Jimmy Carter and former California Governor Ronald Reagan. The small inset photo quotes Ronny Raygun’s famous quip about peaceful protestors, “If it takes a bloodbath, let’s get it over with. No more appeasement.” (Photo: personal collection)

Marx Brothers brand Molotov cocktails!

To bring this article to a conclusion, I am turning to another external source and the opinions of another critic, Charles A. Cassidy Jr in Video Hound’s Groovy Movies — Far-Out Films Of The Psychedelic Era (page 310):

“Viewers may be put off by the ambiguous conclusion, but American International Pictures put this package together with an adroit mixture of dark humor, good music performed by the principals, and the deft use of docudrama footage of ’60s demonstrations and marches on Washington. Campy psychedelia, the downfall of so many groovy movies, is saved for the concert scenes.

The real money shots here are the lampoons of both youth culture and ageism, flung around like Marx Brothers Molotov cocktails. The hip script by Robert Thom persuasively directs the don’t-trust-anyone-over-thirty argument at Fergus, Mrs. Flatow, and other gray-haired, starched, war-stirring, and scotch-swilling Establishment figures, but he doesn’t let the youth movement off easily either.”

Videohound’s Groovy Movies: Far-Out Films of the Psychedelic Era by Irv Slifkin is a fun read with lots of interesting recommendations to movies most of us have never heard of! Slifkin gets to cover a lot of genres because the publishers rather loosely interpret the “Psychedelic Era” as being just about anything from the ’60s. (Photo: personal collection)

Reassessing reality after fifty years

Given the gutting of the American public education system by Rep*blican Congresses over the past thirty-plus years and the growing apathy by those who graduate from that system (voting by Americans ages 18–30 is negligible), maybe we Sixties Survivors need to reassess consensual reality after fifty years.

I posted a complementary part to this article there. “Paying Attention to Conservative Thought in Film, Music, Literature, and Other Lowlife Pursuits” deals with a review of the movie Wild in the Streets that appeared on a conservative website that I stumbled over during my research for the main article above. Should this be of interest, click on over and give it a read.

This article originally appeared on the Rather Rare Records site as “On Wild in the Streets as Political and Social Satire” on May 16, 2017. I eliminated more than a thousand words from that piece and added a few new illustrations.

Maybe we need to modify Weinberg’s exhortation, “We don’t trust anyone under 30!”

(Photo: personal collection)

FEATURED IMAGE: The photo at the top of this page is Max Frost (Christopher Jones) on stage with members of his band Sally LeRoi (Diane Varsi) on keyboards and Billy Cage (Kevin Coughlin) on bass. They are doing a benefit concert for candidate Johnny Fergus (Hal Holbrook). This photo is an 8 x 10-inch black and white publicity still handed out for promotional purposes in 1968.

Postscript

At no time in the movie Wild in the Streets is Max’s band referred to as the Troopers. In fact, Sidewalk/Tower Records used the name Max Frost & the Troopers on tracks recorded and released on earlier soundtrack albums! There never was a group with that name and the tracks credited to them—including the entire album Shapes of Things to Come—feature an assortment of musicians, including Davie Allan. (Maybe.)

___________________________________________________________________

Thanks for reading! Below are links to a pair of articles that are essential to knowing what the Tell It Like It Was publication here on Medium is all about — mostly rock & roll music of the ’50s and ’60s.

Introduction to “Tell It Like It Was”

Excitations and good vibrations about the music of the ’60s

medium.com

Introduction to “The Toppermost of the Poppermost”

All about all of the articles about all of the #1 records of the ‘60s

medium.com

Tell It Like It Was

Articles, essays, conversations, and reviews of music and records from the ’60s and beyond.

Follow

Politics

60s Rock

Counterculture

Wild In The Streets

Movies

WRITTEN BY

Neal Umphred

Follow

Mystical Virgo and pragmatic liberal likes long walks alone in the rain at night with an umbrella and flask of 10-year-old Laphroaig.

FEATURED IMAGE: The photo at the top of this page is Max Frost (Christopher Jones) on stage with members of his band Sally LeRoi (Diane Varsi) on keyboards and Billy Cage (Kevin Coughlin) on bass. They are doing a benefit concert for candidate Johnny Fergus (Hal Holbrook). This photo is an 8 x 10-inch black and white publicity still handed out for promotional purposes in 1968.

Postscript

At no time in the movie Wild in the Streets is Max’s band referred to as the Troopers. In fact, Sidewalk/Tower Records used the name Max Frost & the Troopers on tracks recorded and released on earlier soundtrack albums! There never was a group with that name and the tracks credited to them—including the entire album Shapes of Things to Come—feature an assortment of musicians, including Davie Allan. (Maybe.)

___________________________________________________________________

Thanks for reading! Below are links to a pair of articles that are essential to knowing what the Tell It Like It Was publication here on Medium is all about — mostly rock & roll music of the ’50s and ’60s.

Introduction to “Tell It Like It Was”

Excitations and good vibrations about the music of the ’60s

medium.com

Introduction to “The Toppermost of the Poppermost”

All about all of the articles about all of the #1 records of the ‘60s

medium.com

Tell It Like It Was

Articles, essays, conversations, and reviews of music and records from the ’60s and beyond.

Follow

Politics

60s Rock

Counterculture

Wild In The Streets

Movies

WRITTEN BY

Neal Umphred

Follow

Mystical Virgo and pragmatic liberal likes long walks alone in the rain at night with an umbrella and flask of 10-year-old Laphroaig.