(by Ralph Solecki, published 1971)

AISC January 2017 Newsletter Page 5

FROM OUR LIBRARY THIS MONTH

http://www.angloiraqi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Anglo-Iraqi-Studies-Centre-newsletter-January-2017.pdf

This book was published by the American anthropologist Professor Ralph Solecki (1917-1988) of Columbia University, who excavated the caves of northern Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan) between 1951 and 1960.

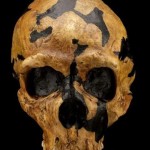

During this time, he found and excavated the Shanidar cave in northern Iraq, which is famed for the fossilized remains of early humans (neanderthals) found there.

Solecki found many fossilized remains of neanderthals, who were buried with their flowers, and this is why he named his book “The First Flower People”. These neanderthals had

lived in the area around 40,000 years ago, and later researches suggested even earlier than this, long beforethe birth of civilisation in Mesopotamia and the world.

In 1957, Solecki and his team of anthropologists recovered the fossilised remains of 10 individuals from tens of thousands of years ago.

This was considered a grand find in the history of human evolution;Solecki’s findings indicated that these early humans may have practised early medicine and ritual burial.

Solecki is pictured here in northern Iraq, with a Kurdish assistant, during

his excavations of the area. Also pictured is Shanidar Cave, the place of Solecki’s findings.

Search Resul

Web results

SHANIDAR: The First Flower People

The last decade has done much to restore Neanderthal man to the ranks of humanity -- a benign good fellow who may have become extinct, may or may not have been a sub-race of Homo sapiens, and so on, but at least from the evidence seems to have possessed the ""full gamut of human feelings, from belligerence to love and compassion."" The extraordinary finds of Solecki at Shanidar Cave in Iraq enhance this image. A paleobotanist examining the soil residue in an area where Neanderthal skeletons were found (the first in this part of the world) revealed the startling fact that a variety of flowers were found also; from their distribution and position the implication was that they had been laid there deliberately as a funeral offering. Thus the First Flower People of Solecki's subtitle. The story of the dig at Shanidar and its rich repository of remains is told in this short excellent work, scholarly in its approach and modest in the presentation. The cave, a large shelter that has been occupied on and off over a period of 100,000 years, makes a fascinating raise en scene. For while Solecki and his colleagues were digging, the cave was occupied by families of Kurds who take shelter for a few months of the year along with their horses, goats, dogs, and chickens. The interactions of the two groups are not without their comic value but on the whole the Kurds remain mysterious -- Solecki sounds almost like a 19th century writer describing these wild mountain people living in isolated valleys, fierce, brave, etc. Indeed the fascinating counterpoint of modern Kurd and ancient Neanderthal runs through the book as a subtle background theme. In the end it would seem that the mystery of the modern Kurd is only mildly surpassed by the long dead inhabitants of that same terrain.

The Shanidar IV ‘Flower Burial’: a Re-evaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual

Jeffrey D. Sommer

Cambridge Archaeological Journal / Volume 9 / Issue 01 / April 1999, pp 127 - 129

DOI: 10.1017/S0959774300015249, Published online: 14 October 2009

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0959774300015249

https://afanporsaber.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/The-Shanidar-IV-%E2%80%98flower-burial%E2%80%99-a-re-evaluation-of-neanderthal-burial-ritual.pdf

The Bioarchaeology of Care

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310771734_Tilley_L_2012_The_bioarchaeology_of_care

Abstract:

In archaeology, human skeletal remains are often dealt with separately from their social context. However, by taking a biocultural approach to reconstruct both biological identity and sociocultural context, the discipline of bioarchaeology can be used to diminish this divide concerning the human body and can provide important perspectives on human behaviours. One such behaviour is caregiving, and this paper explores the ability of bioarchaeology to identify evidence of human caregiving from human remains. Tilley’s (2012) four-stage “bioarchaeology of care” methodology is reviewed as a framework for future researchers to follow. The capacity of bioarchaeology to interpret caregiving behaviour using theories of biocultural evolution and identity of the body is also explored. Although there still exists some limitations, by modeling Tilley’s (2012) methods, drawing upon social theory, and using individual case studies to make inferences about populations, bioarchaeology can provide an interdisciplinary, unique, and critical perspective on human caregiving. Keywords: Bioarchaeology; Paleopathology; Caregiving; Disability; Biocultural Approach.

Neandertal Man the Hunter: A History of Neandertal Subsistence

vis-à-vis: Explorations in Anthropology, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 58–80.

vav.library.utoronto.ca

This article © 2010 Elspeth Ready

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada license.

ELSPETH READY, Department of Anthropology, Trent University

New investigations at Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan. Antiquity: A Review of World Archaeology. (2015) PDFhttps://afanporsaber.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/The-Shanidar-IV-%E2%80%98flower-burial%E2%80%99-a-re-evaluation-of-neanderthal-burial-ritual.pdf

BOOK

This now outdated and out-of-print book is a must-read for those not only interested in the Shanidar Neanderthals, but also in the process and even adventure of palaeoanthropological discovery. Interestingly, Ralph Solecki ended up in Iraq only because he couldn't get into Yemen, his originally intended location for surveying. This book brilliantly and engagingly details how he went about prospecting for early human sites, how he came to suspect the Shanidar cave's potential and his many discoveries therein. It also includes fascinating details such as the fact that families of local Iraqi Kurds were still living in the cave when they started excavating it, and their relationships and attitudes towards each other -- and towards the dynamite the archaeological team was using! Shanidar became a very significant Neanderthal site because of the so-called "flower burial": the Neanderthal known as Shanidar IV was discovered in a location rich in flower pollen; it was therefore claimed that this Neanderthal was buried with flowers, meaning that they were involved in ritual and emotion which had hitherto been seen as exclusively a Homo sapiens trait. As Solecki writes: "With the finding of flowers in association with Neanderthals, we are brought suddenly to the realization that the universality of mankind and the love of beauty go beyond the boundary of our own species." This is a complicated and now very controversial claim, with others arguing that the pollen was introduced by rodents, as there are many burrows in the sediment. (Keep an eye on the on-going analyses of Professor Graeme Barker's team.)

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310771734_Tilley_L_2012_The_bioarchaeology_of_care

Abstract:

In archaeology, human skeletal remains are often dealt with separately from their social context. However, by taking a biocultural approach to reconstruct both biological identity and sociocultural context, the discipline of bioarchaeology can be used to diminish this divide concerning the human body and can provide important perspectives on human behaviours. One such behaviour is caregiving, and this paper explores the ability of bioarchaeology to identify evidence of human caregiving from human remains. Tilley’s (2012) four-stage “bioarchaeology of care” methodology is reviewed as a framework for future researchers to follow. The capacity of bioarchaeology to interpret caregiving behaviour using theories of biocultural evolution and identity of the body is also explored. Although there still exists some limitations, by modeling Tilley’s (2012) methods, drawing upon social theory, and using individual case studies to make inferences about populations, bioarchaeology can provide an interdisciplinary, unique, and critical perspective on human caregiving. Keywords: Bioarchaeology; Paleopathology; Caregiving; Disability; Biocultural Approach.

Tilley 2015 Theory and Practice in the Bioarchaeology of Care - Overview and chapter abstracts.pdf

Building a Bioarchaeology of Care

'Bioarchaeology of care' is a formal framework for analyzing cases of past caregiving in a contextualized and systematic manner. In bioarchaeology, health-related care is inferred from evidence in human remains that indicate survival with a disabling pathology when the individual would likely not have reached the actual age at death without care. Caregiving practices can potentially reveal a society's norms, values and beliefs. Additionally, caregiving can provide insights into societal knowledge, skills and experiences as well as political, economic, social and environmental variables. Despite its potential for providing a window into such aspects of past behavior, caregiving has been neglected as a topic for archaeological research. To alleviate this problem the Index of Care was created as an on-line instrument supporting application of a bioarchaeology of care methodology. Building a Bioarchaeology of Care consists of perspectives from three continents for developing theory and practice into a cohesive framework. Presenters will discuss the possibilities and pitfalls for Index of Care use, explore approaches for integrating care analysis in other areas of archaeology (e.g. mummification literature in context of caregiving), identify new directions for research, and propose strategies for communicating findings and stimulating debate.

Neandertal Man the Hunter: A History of Neandertal Subsistence

vis-à-vis: Explorations in Anthropology, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 58–80.

vav.library.utoronto.ca

This article © 2010 Elspeth Ready

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada license.

ELSPETH READY, Department of Anthropology, Trent University

ABSTRACT

The history of Neandertals has been examined by a number of researchers who

highlight how historical biases have impacted popular and scientific perceptions

of Neandertals. Consequently, the history of Neandertals is relevant to current

debates about their relationship to modern humans. However, histories of

Neandertal research to date have focused on changes in beliefs regarding the

Neandertals’ relationship to modern humans and correlated shifts in perceptions

of their intelligence and anatomy. The development of ideas about Neandertal

subsistence has generally not been discussed. This paper intends to correct this

oversight. Through an historical overview of Neandertal subsistence research,

this paper suggests that ideas about Neandertal subsistence have been affected

by historical trends not only within archaeology, but also in anthropological and

evolutionary theory.

The history of Neandertals has been examined by a number of researchers who

highlight how historical biases have impacted popular and scientific perceptions

of Neandertals. Consequently, the history of Neandertals is relevant to current

debates about their relationship to modern humans. However, histories of

Neandertal research to date have focused on changes in beliefs regarding the

Neandertals’ relationship to modern humans and correlated shifts in perceptions

of their intelligence and anatomy. The development of ideas about Neandertal

subsistence has generally not been discussed. This paper intends to correct this

oversight. Through an historical overview of Neandertal subsistence research,

this paper suggests that ideas about Neandertal subsistence have been affected

by historical trends not only within archaeology, but also in anthropological and

evolutionary theory.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295932234_New_investigations_at_Shanidar_Cave_Iraqi_Kurdistan

Schematic cross section of the Solecki excavation, showing his major cultural layers, the key radiocarbon dates and the relative positions of the Neanderthals (reproduced with kind permission of Ralph Solecki)

The eastern extension of the Solecki trench in 1960, where most of the Neanderthal remains were found; this area is the main focus of the new excavations (reproduced with kind permission of Ralph Solecki).

General view of the excavation area, looking east, showing the locations mentioned in the text; scales: 2m and 0.5m (photograph by G. Barker).

A variety of burins and (bottom right) an endscraper from the sediments of Baradostian age (illustration by T. Reynolds).

The human right tibia and fibula in articulation with ankle bones near Solecki's Shanidar V Neanderthal skeletal material and probably part of the same group; scale: 8cm (photograph by G. Barker).

https://www.cambridge.org › core › journals › antiquity › article › new-nean...

by E Pomeroy - 2020 Feb 18, 2020 - DOI: https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.207; Published online by Cambridge ... site following Ralph Solecki's mid twentieth-century discovery of ... Solecki argued that some of these individuals had died in rockfalls ... close to the 'flower burial' location—the first articulated Neanderthal ... Solecki, R.S. 1971.

Neanderthal medicine? - eScholarship.org

AbstractIn 1856, a skeleton was found in a cave in the Neanderthal valley near Düsseldorf, Germany.

After a long discussion, whether these bones would belong to a recent human being suffering from a disease, i.e. rachitis, it became accepted at the end of the nineteenth century, that, together with numerous similar remains from France and Belgium, these bones belong to a different species, Homo neanderthalensis. Neanderthals belong to a branch of the human evolutionary tree; they evolved from Homo heidelbergensis and lived during the ice ages in Western Europe, the

middle East and West Siberia. Neanderthals got extinct about 40,000 years ago. The Neanderthal remains from the Neanderthal valley belong to an approximately 40 year old male, who suffered from numerous injuries and illnesses during lifetime such as a broken ulna and meningitis, which he apparently survived. This probably shows that he could only survive, because his group took

care of him [1]. There a numerous examples from the Shanidar cave in northern Iraq, that have been excavated between 1950 and 1960 by Ralph Solecki, showing similar signs of diseases or injuries [2]. Shanidar I was a male of about 40-50 years. He was handicaped since childhood or

early adulthood and died by a rock fall. His skull showed a deformation of the orbita due to crushing injury, most probably causing blindness of the left eye. His right arm was completely atrophied, either due to amputation or an extreme osteomyelitis years before his death. Two hearths were found in the vicinity of the skeleton, i.e., he probably watched the fire. An atypical abrasion of the teeth, indicating the use for heavy chewing (for example leather, like Inuit people did until recent times), shows that he made himself useful around the hearth. Shanidar III was

wounded by a spear in his chest, which stuck in his ribs. He survived at least two weeks, because the gouge in his bone had started to heal [2,3]. The most interesting remain in terms of “medicine” is Shanidar IV, the “flower burial”. Earth probes around the skeleton revealed pollen of plants, such as horse tail (German: Schachtelhalm), senecio (Kreuzkraut), hollyhock (Malve),cornflower (Kornblume), grape hyazinth (Traubenhyazinthe), and yarrow (Schafgarbe), plants

that are used as medical plants since ancient and medieval times until today [2]. There is increasing evidence that Neanderthals might have used these plants as medical plants by data from the El Sidrón cave in Spain (about 50000 years go) [4]. Analysis of the calculus of an adult Neanderthal revealed that this individual ate a range of cooked carbohydrates. The organic

compounds azulene and coumarin were found, consistent with yarrow and camomile. The authors propose that “the Neanderthal occupants of El Sidrón, …..had a sophisticated knowledge of their natural surroundings, and were able to recognize both the nutritional and the medicinal value of

certain plants. Although the extent of their botanical knowledge and their ability to self-medicate must of course remain open to speculation…”

Today, there is strong archaeological evidence that Neanderthals were real human beings that took care of each other. Their skeletal remains clearly show that they were able to treat even severe injuries and illnesses and that they used medical plants.

References

[1] Spikins PA, Rutherford HE, Needham AP. From homininity to humanity: Compassion

from the earliest archaics to modern humans. Time Mind 2010;3:303–26.

doi:10.2752/175169610X12754030955977.

[2] Solecki RS. Shanidar, the first flower people. 1st ed. Knopf; 1971.

Smithsonian Collections Blog

Highlighting the hidden treasures from over 2 million collections

Tuesday, June 18, 2019

Discovering Culture in the Shanidar Cave Neanderthals

Often, Neanderthals are thought of as a robust and brutish distant relative of modern humans. With their stout features and receding foreheads, the similarities between them and us seem scant at first, but in fact important parallels exist.

Shanidar I excavation photo, 1957 [1].

Between 1957 and 1960, a total of nine Neanderthal individuals were recovered by archaeologist Ralph S. Solecki and local laborers in Shanidar Cave, Iraq. Fragments of lower leg bones of a tenth Neanderthal individual, an infant, have also been found, mixed in with the Shanidar animal fossil remains in the Smithsonian collections. These discoveries date to the Mousterian era at approximately 100,000 to 35,000 years ago. Neanderthals looked different from modern humans and through the 1950s had erroneously been thought to be less evolved, yet both species engaged in complex social behaviors, including care for sick or infirm individuals and symbolic beliefs.

Culture is a phenomenon found in all human societies and behaviors similar to what we would consider cultural in modern humans were carried out by Neanderthals. For example, like humans, Neanderthals learned to create tools and ornaments made of stone and bone [2]. During the excavations of Shanidar Cave, hearths or firepits were unearthed, which may offer insight into the life habits of Neanderthals. Neanderthals had the capacity to start and maintain fires, and many of the hearths appear to have been strategically built against stones to give off reflective heat [2, 3]. The size of the hearths suggests that some were for communal use and others were reserved for smaller groups, possibly families [3]. Based on this evidence, some scientists believe that like modern humans Neanderthals formed groups and bonds among each other and very likely gathered around the hearths for meals and other activities that point to social practices [3].

Illustration of the hearths excavated at Shanidar Cave,

circa 1957-1960 [1].

Mortuary practices, or behaviors associated with the treatment of the dead, are frequently an index of complex cultural practices. In archaeology, mortuary practices are one way to learn about cultural beliefs. In 1960, Ralph Solecki uncovered a male Neanderthal, aged approximately 40 years at time of death, during the fourth excavation season at Shanidar Cave. The individual, Shanidar IV, was found 7.5 meters below the modern cave floor in damp, brown, sandy soil. This soil was looser than what the excavators had previously encountered and indicated a burial. Shanidar IV was positioned on his left side with head placed towards the south. [4, 5, 9]. Through analysis of the Shanidar IV Neanderthal burial, specifically the soil samples collected during excavation, archaeologists like Ralph Solecki believed that the Shanidar IV skeleton may have been an intentional Neanderthal burial.

Shanidar IV was found on its side in a bent position [1].

In 1975, a palynologist, or a scientist who studies pollen, Arlette Leroi-Gourhan published information regarding the soil samples taken from Shanidar Cave [6]. The samples showed tree pollen that could have blown into the cave by wind, but other samples contained pollen from at least eight species of small, brightly colored flowers that were relatives of hollyhock, yellow flowering groundsel, bachelor’s button, and grape hyacinth, all found today growing around the surrounding hillsides [6]. While this theory has been disputed by later scholars, Leroi-Gourhan suggested that the flower pollen was not brought into the cave by the wind or animals, but perhaps by the Neanderthals for a funerary ritual. The presence of Malvaceaes – a large, singular flower covered in spikes—seemed to suggest that the Neanderthals living at the cave at the time had wandered in search of the flower to place within the grave. This interpretation pointed toward higher cognitive ability within Neanderthals, according to Ralph Solecki [4, 5].

Malvaceae was one of the flower families found

in the soil sample taken from around Shanidar IV [1].

Other anthropologists, who reasoned that Neanderthals were not using flowers in funerary practices, disagreed with Ralph Solecki’s interpretation of Shanidar IV. These interpretations stated that wind was able to carry the pollen through the large mouth of the cave [7]. Additionally, rodent species found in the cave are known to burrow and store plant materials, including flowers. These rodents might have been responsible for some of the deposition of the pollen found near Shanidar IV [8]. The pollen samples collected from the burial pit also included tiny fragments of wood and pollen grains of evergreens such as fir, suggesting to some researchers that tree boughs could have been brought to the burial site in addition to clusters of colorful flowers (6). The debate on whether the pollen samples found from around Shanidar IV are indicative of intentional funerary practices or whether the pollen came into the cave through other means continues today. If funerary, this has implications for how Neanderthals and even our own ancestors interacted with and interpreted the world around them.

Due to the extreme rarity of paleontological and archaeological evidence relating to human ancestors living tens of thousands of years ago, our comprehension about the human

lineage is often limited. Therefore, the wealth of archaeological evidence accompanying the Neanderthal remains at Shanidar Cave uncovered by Ralph and Rose Solecki has fundamentally shaped how we understand Neanderthals and our knowledge about the past. Two important goals of archaeologists like the Soleckis are to attempt to give those who lived in the past a voice and for others to have access to this information. These excavations and the Soleckis’ work have inspired new excavations at Shanidar Cave, which will broaden our understanding of how people occupying this cave adapted to their environment [10, 11]. Moreover, the Ralph S. and Rose L. Solecki Papers and Artifacts Project is processing the professional papers and cataloging the artifact collections of the Soleckis, including material from the Shanidar Cave excavations, in order to make them more accessible to researchers as well as the public.

Ralph S. and Rose L. Solecki papers - contents · SOVA

To learn more about the Ralph S. and Rose L. Solecki Papers and Artifacts Project, check out previous Solecki Project Smithsonian Collections Blog posts. Also, explore the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program’s Snapshot in Time about Shanidar Cave. The Ralph S. and Rose L. Solecki Papers and Artifacts Project was made possible by two grants from the Smithsonian Institution’s Collections Care and Preservation Fund.Viridiana Garcia and Kayla Kubehl, Interns, Spring 2019

Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History

Sources

[1] The Ralph S. and Rose L. Solecki papers, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

[2] Matt Cartmill, Kaye Brown, and Fred H. Smith, The Human Lineage. (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

[3] Ralph S. Solecki. “Living Floors in the Middle Palaeolithic Deposits at Shanidar Cave, Northern Iraq.” Unpublished, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

[4] Ralph S. Solecki, 1975. “Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal burial in Northern Iraq.” Science 190 (4217), pp. 880-881.

[5] Ralph S. Solecki, Shanidar: The First Flower People (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971).

[6] Arlette Leroi-Gourhan, 1975. “The flowers found with Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal burial in Iraq.” Science 190 (4214), pp. 562-564.

[7] Robert H. Gargett et al., 1989. “Grave shortcomings: The evidence for Neanderthal burial.” Current Anthropology 30 (2), 157-190.

[8] Jeffrey D. Sommer, 1999. “The Shanidar IV ‘Flower Burial’: A re-evaluation of Neanderthal burial ritual.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 9 (1), pp. 127-129.

[9] Ralph S. Solecki, Shanidar, The First Flower People (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971).

[10] Tim Reynolds, William Boismier, Lucy Farr, Chris Hunt, Dlshad Abdulmutalb and Graeme Barker, 2015. “New investigations at Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan.” Antiquity: A Review of World Archaeology vol. 89, no. 348

[11] Elizabeth Culotta, 2019. “New remains discovered at site of famous Neanderthal ‘flower burial’” Science, doi:10.1126/science.aaw7586

Search Results

Web resul

by E Pomeroy - 2017 - Cited by 20 - Related articles

Excavations led by Ralph Solecki from 1951 to 1960 at Shanidar Cave in the Zagros ... radiocarbon date from charcoal associated with Shanidar 1 (Solecki, 1971). ... The first is whether the material can be confidently identified as Neanderthal. ... distinguishing between published data on Neanderthals, Late Pleistocene H.

Julian E Reade

JR Anderson

Prehistoric Archaeology,

Kurdish Studies,

Archaeological Heritage Management

Report on prospects for archaeological work at Shanidar and elsewhere in Iraqi Kurdistan, 2009.

plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets

(Shanidar III, Iraq; Spy I and II, Belgium)

https://www.pnas.org/content/108/2/486

Amanda G. Henrya,b,1, Alison S. Brooksa

, and Dolores R. Pipernob,c,1a

Department of Anthropology, Center for Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology, Washington, DC 20052; b Archaeobiology Laboratory, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013-7012; and c Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Box 2072 Balboa, Panama Contributed by Dolores R. Piperno, November 12, 2010 (sent for review July 7, 2010)

Health-related care for the Neanderthal Shanidar 1

http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n2558/pdf/article07.pdf

LAURA KENT

Abstract

The bioarchaeology of care methodology is used to identify health-related care for prehistoric hominids using the skeletal indications of survival with a disability or debilitating disease that would have resulted in death if care was not given. This model involves four stages and was applied to the Neanderthal Shanidar 1 in order to evaluate the type of care possibly received by the individual and what this caregiving behaviour suggests about Neanderthal culture and behaviour. The skeletal remains of Shanidar 1 represents an adult male of advanced age who suffered from a number of debilitating pathologies that would have affected his ability to survive and contribute to his social group. Shanidar 1 required health-related care in the form of direct support and accommodation of a different role within the social group in order to survive to his age at death. The survival of Shanidar 1 to old age implies Neanderthals were capable of changing their behaviour in order to care for and accommodate injured members of their social group. This evidence of health-related care for Shanidar 1 suggests Neanderthals had a greater level of behavioural flexibility and social complexity than previously believed.

First ‘flower people’: Neanderthal grave is sign of elaborate funerals

Rhys Blakely, Science Correspondent

Tuesday February 18 2020, 12.00pm GMT, The Times

The discovery of Shanidar Z in Iraqi Kurdistan was the first of its kind in decades

GRAEME BARKER/UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE/PA

The first Neanderthal skeleton to be unearthed in decades promises to settle a debate over whether these ancient cousins of modern humans held sophisticated funeral rituals that made them the first “flower people”.

The remains, thought to be about 70,000 years old, were discovered in Shanidar Cave, in the foothills of Iraqi Kurdistan.

Crucially, the skeleton — called Shanidar Z — appears to have been deliberately buried in a grave-like hollow that also contains plant matter such as pollen.

Cambridge University and Liverpool John Moores University are carrying out tests to discover if the find supports a long-contested theory that Neanderthals held elaborate rites, including burying their dead with flowers.

The Shanidar site was first excavated in the 1950s and 1960s, when the late American

Rhys Blakely, Science Correspondent

Tuesday February 18 2020, 12.00pm GMT, The Times

The discovery of Shanidar Z in Iraqi Kurdistan was the first of its kind in decades

GRAEME BARKER/UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE/PA

The first Neanderthal skeleton to be unearthed in decades promises to settle a debate over whether these ancient cousins of modern humans held sophisticated funeral rituals that made them the first “flower people”.

The remains, thought to be about 70,000 years old, were discovered in Shanidar Cave, in the foothills of Iraqi Kurdistan.

Crucially, the skeleton — called Shanidar Z — appears to have been deliberately buried in a grave-like hollow that also contains plant matter such as pollen.

Cambridge University and Liverpool John Moores University are carrying out tests to discover if the find supports a long-contested theory that Neanderthals held elaborate rites, including burying their dead with flowers.

The Shanidar site was first excavated in the 1950s and 1960s, when the late American

Were the Neandertals Our Ancestors?

On an August day in 1856, in the Neandertal Valley

in northwestern Germany, a workman in a lime-

stone quarry uncovered the bones of what he

thought was a cave bear. He put them aside to show to Johann

Fuhlrott, the local schoolteacher and an enthusiastic natural

historian.

Fuhlrott immediately realized this was something much more

significant than the bones of a bear. The head was about the size

of a man’s, but it was shaped differently, with a low forehead,

bony ridges above the eyes, a large projecting nose, large front

teeth, and a bulge protruding from the back. The body, to judge

from the bones that were recovered, must also have resembled a

man’s, though he would have been shorter and stockier—and far

more powerful—than any normal man. Making the bones even

more significant, Fuhlrott realized, was that they’d been found

amid geological deposits of great antiquity.

The schoolteacher contacted Hermann Schaaflhausen, a pro-

fessor of anatomy at the nearby University of Bonn. He, too,

recognized that the bones were extraordinary: “a natural con-

formation hitherto not known to exist,” as he later described

them. Indeed, what the workman had uncovered, Schaafflhausen

believed, was a new—or rather a very, very old—type of human

Title: Unsolved Mysteries of History: An Eye-Opening Investigation into the

Most Baffling Events of All Time

Author: Paul Aron

ISBN: 0-471-35190-3

Shanidar Cave index

#Shanidar Instagram Posts

Neandertal Burial Practices

Research Paper for Human Prehistory and Anthropology 2013 by Darci Clark

The study of Neandertal (or Neanderthal either is correct) burials has caused much debate in the academic world. The topics under discussion range from whether Neandertals deliberately interred their dead to their possible use of grave offerings and ritual practices, which may or may not have included post-mortem defleshing or cannibalism. An excavation of Neandertal burials in Shanidar Cave, Iraq by Ralph Solecki in 1960 caused controversy when flower pollen was discovered in a burial site. This led Solecki to conclude the occupant, called Shanidar IV, was deliberately interred on a bed of flowers. Although today Solecki’s interpretation has been disregarded, it is a good example of the controversies surrounding the cognitive abilities of Neandertals.

Solecki excavated nine Neandertals at Shanidar Cave between 1951 and 1960. Rock falls in the cave were the probable cause of death for several of the individuals, but others appeared to have been buried deliberately. Evidence of animal remains, hearths and ashes indicated these individuals had occupied the cave before their accidental death or burial at the site. Those that had been killed by the rock falls had only partial skeletal remains while the deliberately buried remains were mostly complete. Seven adults and two infants were unearthed and four of the skeletons had been placed on top of one another. This could indicate one multiple burial or a series of single burials.

These four skeletons, called Shanidar IV, VI, VII, and VIII are the best evidence for deliberate burials at the site. Shanidar VIII was an infant, Shanidar VI and VII were adult females, and Shanidar IV was an adult male. The infant was buried first, followed by the two females placed adjacent to each other, and then finally the adult male. There was also evidence of possible funerary caching at the site in the case of the remains of Shanidar III. Funerary caching is the practice of placing remains in a natural feature, such as a fissure or the back of a cave, without making any modifications to the location.

The excavations at Shanidar grew controversial over the analysis of a routine soil sample. Solecki took six soil samples from the area around Shanidar IV and Shanidar VI in addition to areas where no remains had been found. The analysis was performed by paleobotanist Arlette Leroi-Gourhan several years later. She discovered not only pollen from trees and grasses, but pollen from at least seven species of wild flowers as well. While there were sparse traces of pollen from all parts of the cave, the pollen from the burial area was concentrated in large clusters and was resting in the part of the stamen that contains the pollen. Leroi-Gourhan concluded neither wind, birds, or animals could have deposited the floral pollen in the cave.

The discovery that the remains of a Neandertal had been placed on a bed of flowers was unlike anything archaeologists had ever found in an early burial site. Solecki said of the unprecedented find that “the simplest explanation appears to be that no one had ever thought of looking for pollens in graves.” This led Solecki to conclude that the Shanidar Neandertals were the first “Flower People” who were capable of human feelings by appreciating the beauty of placing flowers on a grave.

Today most researchers have disregarded Solecki’s interpretation of this evidence. Ironically, his own description of the site led to this reversal of thought. Solecki describes numerous rodent holes close to the skeletal remains and his assumption was the “animals must have been looking for the flesh of the dead.” He even mentions that the holes were used to determine the possible location of human remains. Solecki would “plot the number and angle of the rodent holes, because they seemed to be most numerous around human bones, and seemed to zero in on them from different directions.”

The gerbil-like rodent which may have been responsible for these holes, called Meriones persicus, is native to the area around Shanidar. Research on the burrows of a similar species called, Meriones crassus, indicates the rodents may have indeed been responsible for the flower pollen evidence which was found in the cave. Evidence that the Meriones crassus had kept flower heads in its burrows was found, in addition to seeds, leaves, and other plant material. Furthermore, the amount of flower heads that were found could easily account for amount of pollen at the Shanidar burial site. If that is the case, Solecki and Arlette Leroi-Gourhan were mistaken in their analysis that animals could not have been responsible for the pollen in the cave. Coupled with the fact that the Meriones persicus was likely responsible for the flower pollen in the burial, no similar pollen evidence has ever been found at any other location. Regardless of his interpretation of the pollen in the burial site, Solecki’s work at Shanidar is still an important Neandertal discovery due to the number and quality of the remains discovered and the academic controversy which has surrounded it.

Enough evidence has been found at thirty Neandertal excavated sites to indicate they were practicing a number of deliberate mortuary activities.One of those activities is funerary caching, which as mentioned before, involves the disposal of remains in a pre-existing natural location. This practice may have started as a way to keep decaying bodies away from the areas inhabited by the living. Placing remains in naturally protected areas such as caves and fissures could have been done to protect the remains from predators. Moving the remains away from living areas would also have guaranteed predators would not be drawn by the scent of decaying flesh. Funerary caching may have taken place at the excavated sites in Caverna (Grotta) delle Fate, Italy, La Quina, Charente, El Sidrón Cave, Spain, and Krapina, Croatia where numerous skeletal remains were found. Even though the practice of funerary caching is not considered a true burial, its use implies that Neandertals understood the idea that the dead needed to be disposed of in an appropriate place.

There is some evidence that Neandertals practiced cannibalism, also called post-mortem defleshing. At the aforementioned El Sidrón Cave in northern Spain, the remains of twelve bodies have been excavated which may have been murdered then cannibalized by other Neandertals. The remains consisted of three adult males, three adult females, three male adolescents, two children, and one infant. Cannibalism was suspected in this case because the bones had been cut open with stone tools to retrieve the marrow and some skulls had been smashed to remove the brain. The remains also show evidence of skinning and intentional disarticulation, meaning the separation of two bones at the joint. While the evidence is strong for cannibalism at this site, it is important to note that some remains still had the skulls intact. This indicates there may have been another purpose for the post mortem processing other than just nutritional cannibalism.

Additional evidence of possible cannibalism has been found at the Krapina, Croatia site as well. Similar to the remains at El Sidrón Cave, some of the skulls were smashed and bones were intentionally broken to remove the marrow. The bones of these remains were also burned. The remains of twenty-three individuals were discovered at Krapina consisting of fourteen adults, four adolescents, and five infants. Of those remains, only one cranium had cut marks which exhibited evidence of scalping. The Krapina site differed from Shanidar and El Sidrón because it was a natural rock shelter which may have been actually been inhabited. The discovery of Middle Paleolithic tools as well as animal remains offered evidence for habitation.

The subject of Neandertal cannibalism has caused much discussion in academia regarding the purpose of this practice. There seems to be little doubt that some remains were subjected to some kind of soft tissue processing after death. The primary purpose of processing, or defleshing, of the remains may have been for other Neandertals to consume, but it also could have been some type of funerary ritual which developed out of concern for the body. If indeed the purpose of the defleshing was cannibalism, the question remains whether the individuals were intentionally murdered for consumption as suggested by the evidence at El Sidrón Cave. Cannibalistic societies consider it a cult practice in which the brain and bone marrow are consumed to absorb the qualities of another, or to conquer the spirit of an enemy. It seems unlikely that cannibalism would have been considered a normal method of food provision, so the practice of defleshing could have served a spiritual or ritual aspect, in addition to offering a form of sustenance.

The evidence for deliberate burial is strong in several European and Near Eastern sites. Even though the evidence at these sites prove some Neandertals buried their dead, it does not prove that the practice was performed for each death or that it was even performed by all Neandertal groups.Generally, the fact that so many sites with remains have been found intact is strong evidence in itself that the remains were deliberately buried. Without deliberate burial the remains would probably not have survived decay or destruction by predators. Even if Neandertals did not experience our burial process of grieving and honoring the dead, the burial evidence found in such a widespread area definitely shows some motive for deliberate inhumation.

Red ochre has been found in Neandertal graves at La Ferrassie and La Chapelle-aux-Saints in France as well as Spy Cave in Belgium. The meaning or significance of the red ochre is not known but its ritual use could be further evidence of deliberate burial.Red ochre is a natural pigment derived from hematite, and has been found in later Upper Paleolithic burial sites and cave paintings. Intentional inhumations can also be identified by the placement of the remains. Bodies were placed in their graves lying on one side in a flexed position, similar to the fetal position. Those bodies which were deliberately buried were also fully articulated, meaning all the joints were intact.

The graves at several sites, including the aforementioned La Chapelle-aux-Saints, La Ferrassie, and Shanidar IV, VI, VII, and VIII, are generally accepted as deliberate burials. A nearly complete adult skeleton was discovered in a rectangular pit at the entrance to the cave at La Chapelle-aux-Saints. The fact that the pit was rectangular shaped with straight walls and a flat bottom is a strong indication that the pit had been intentionally dug for the grave, since a naturally formed pit would not have those types of features. At La Ferrassie the nearly complete articulated skeletal remains of an adult male and an adult female, plus the remains of three children and one fetus were discovered buried together in a clear cut grave. One of the children, approximately three years old, also had near complete skeletal remains, which is rare because children’s bones are quite delicate and are not usually found intact.

As discussed before, the remains of Shanidar IV, VI, VII, and VIII are the best examples of deliberate burials at Shanidar Cave. The sequential order of the burials, where the child was buried first, followed by the two adult females, and then finally the adult male suggested the remains were interred over a short amount of time. These skeletal remains for all these individuals were articulated as well. Although articulation is an important indicator of intentional burial, by itself it does not offer enough proof. Articulated remains in conjunction with a burial structure or pit, such as those found in La Chapelle-aux-Saints and La Ferrassie, or the presence of grave goods offer the best indicators of intentional burial. Grave goods can consist of stone tools, animal bones, and unique rocks.

The interpretation of grave goods can be difficult because it is impossible to know if the objects were intentionally or accidentally added during the internment. It is entirely possible that tools and animal bones may have been on the cave floor and then fell into the graves when they were filled in. Although strong evidence has been found to substantiate Middle Paleolithic grave goods of Home sapiens at Djebel Qafzeh and Skhul Caves in Israel, no indisputable Neandertal grave goods have been found at this time. One of the best cases for Neandertal grave goods was found at Regourdou Cave in France where the remains of an adult was discovered lying on flat bed of stones and covered with a pile of stones, called a cairn. The cairn was topped with a combination of sand and ash, including bear and deer bones as well as flint tools.This site may represent the only “actual constructed tomb for the Middle Paleolithic” due to the placement of layers atop the body.

Based on the research included here it seems highly likely that at least some Neandertal groups intentionally interred their dead. With evidence for deliberate burials discovered in Europe and the Near East the practice appears to have been widespread, although it may not have always been performed. The compelling early evidence at Shanidar of internments on beds of flowers may have been replaced with the mundane explanation of the Meriones persicus’ storage of flower heads, but the idea that Neandertals may have had some funerary rituals is still very intriguing. The controversy over defleshing and cannibalism will likely continue as more Neandertal grave sites are discovered. The evidence discussed here indicates Neandertals may have practiced both defleshing as some type of funerary ritual as well as cannibalism for spiritual or nutritional purposes. Discoveries of the use of red ochre and possible grave goods only add to the evidence for deliberate burials. Hopefully future excavations will uncover indisputable evidence of true Neandertal burials and offer new insights into the world of one of humankind’s closest relatives.

WORKS CITED

Gibbons, Ann. “Grisly Scene Gives Clues to Neandertal Family Structure.”Science Now. Published December 20, 2010. Accessed July 6, 2013. http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2010/12/grisly-scene-gives-clues-to-nean.html?rss=1.

Jordan, Paul. Neandertal. Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Limited, 1999.

Mellars, Paul. The Neanderthal Legacy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996. Pettit, Paul. The Palaeolithic Origins of Human Burial. New York: Routledge, 2011. Riel-Salvatore, Julien and Geoffrey A. Clark. “Grave Markers: Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic Burials and the Use of Chronotypology in Comtemporary Paleolithic Research.” Current Anthropology, Vol. 42, No. 4, August/October 2001. doi:10.1086/321801. Accessed July 13, 2013, 449-479.

Roebroeks, Will, Mark J. Sier, Trine Kellberg Nielsen, Dimitri De Loecker, Josep Maria Parés, Charles E. S. Arps, and Herman J. Mücher. “Use of Red Ochre by Early Neandertals.”PNAS Vol. 109 No. Published online before print January 23, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112261109. Accessed July 13, 2013. 1889-1894.

Schrenk, Friedemann, and Stephanie Miller. The Neanderthals. Translated by Phyllis G. Jestice. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Solecki, Ralph. Shanidar: The First Flower People. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971. Sommer, Jeffrey D. “The Shanidar IV ‘Flower Burial’: a Reevaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal, Vol. 9, Issue 01. April 1999, 127-129. Accessed July 6, 2013. doi: 10.1017/S0959774300015249.

Trinkaus, Erik. The Shanidar Neandertals. New York: Academic Press, Inc., 1983.

Jordan, Paul. Neandertal. Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Limited, 1999.

Mellars, Paul. The Neanderthal Legacy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996. Pettit, Paul. The Palaeolithic Origins of Human Burial. New York: Routledge, 2011. Riel-Salvatore, Julien and Geoffrey A. Clark. “Grave Markers: Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic Burials and the Use of Chronotypology in Comtemporary Paleolithic Research.” Current Anthropology, Vol. 42, No. 4, August/October 2001. doi:10.1086/321801. Accessed July 13, 2013, 449-479.

Roebroeks, Will, Mark J. Sier, Trine Kellberg Nielsen, Dimitri De Loecker, Josep Maria Parés, Charles E. S. Arps, and Herman J. Mücher. “Use of Red Ochre by Early Neandertals.”PNAS Vol. 109 No. Published online before print January 23, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112261109. Accessed July 13, 2013. 1889-1894.

Schrenk, Friedemann, and Stephanie Miller. The Neanderthals. Translated by Phyllis G. Jestice. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Solecki, Ralph. Shanidar: The First Flower People. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971. Sommer, Jeffrey D. “The Shanidar IV ‘Flower Burial’: a Reevaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal, Vol. 9, Issue 01. April 1999, 127-129. Accessed July 6, 2013. doi: 10.1017/S0959774300015249.

Trinkaus, Erik. The Shanidar Neandertals. New York: Academic Press, Inc., 1983.

PALEOLITHIC AGE IN IRAN

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/paleolithic-age

Introduction.

The Paleolithic or ‘Old Stone Age’ begins with the first stone tools some 2.5million years ago in Africa (Gowlett 1992, p. 350),and it ends with the Neolithic or ‘New Stone Age,’ essentially at the beginnings of agriculture. The Paleolithic is conventionally divided into Lower, Middle, Upper, and Terminal or Epi-Paleolithic periods. The Paleolithic is known almost exclusively from lithic artifacts—stone tools, classified in conventional ways into types that are diagnostic of the various periods. There is virtually no information about the perishable tools and devices made of wood, fiber, or skins that may have been in use. Layers in archeological sites typically contain quantities of lithics, bones of animals that were hunted and consumed, and the ash from domestic fires. Paleolithic sites in Iran are known primarily from caves and rock shelters in the central Zagros mountains along with a few sites on the Caspian Sea coast and scattered sites on the desert plateau.

Lower Paleolithic. Found in Africa, the eastern Mediterranean and Europe, the Lower Paleolithic is known for two distinctive tool traditions. The first has hand axes and choppers, along with relatively crude flakes struck from flint or quartzite cores. Such tools are thought to have been made by Homo erectus, an archaic form of human that preceded the Neanderthals. The hallmark tool of the Lower Paleolithic, the hand axe, is virtually unknown east of the Euphrates, whereas west of that river it is commonly found. Iran may belong to a second Lower Paleolithic tradition that extends across eastern Asia and is known for its choppers, chopping tools, and crude flakes (Movius, 1969).

Barda Balka, a site in the Chemchemal (Čamčamāl) valley of the western Zagros, in present-day Iraq, had a mix of choppers, flint flakes and a few small hand axes. Based on geology, the site is thought to date to the end of the last interglacial (older than 100,000 years ago), a relatively warm period when there were elephants and rhinos, as well as sheep, goats, and onagers, on the landscape (Braidwood and Howe, 1960; Wright and Howe, 1951). A few hand axes have turned up on the surface in Iran (Braidwood, 1960), but none has come from a secure archeological context, and it is possible that they may be Middle Paleolithic in date, as suggested by the occasional presence of hand axes in Middle Paleolithic tool assemblages. Other sites with possible Lower Paleolithic material, but not hand axes, have been reported from the Central Zagros (Biglari et al., 2000), Azerbaijan (Sadek-Kooros, 1974, 1976), Fārs (Rosenberg, 1988, p. 452), Khorasan (Ariai and Thibault, 1975-77), and Baluchistan (Hume, 1976). Sites as old as 800,000 years have been discovered in Central Asia, suggesting that occurrences of similar age may be found in Iran (Davis and Ranov, 1999).

Middle Paleolithic-Mousterian. Middle Paleolithic sites are known from the Taurus mountains (Minzoni-Deroche, 1993), the Zagros mountains (see below), Uzbekistan (Movius, 1953), several sites in Central Asia, one of which is dated to 200,000 years ago (Davis and Ranov, 1999: p.191), and Afghanistan (Dupree and Davis, 1972). Despite the limited extent of investigations in Iran, there are many Middle Paleolithic sites, although few have been excavated and published in full. In the Levant, the Middle Paleolithic extends back more than 200,000 years and terminates 40,000 years ago. The true age of the Mousterian in the Zagros is not known, although carbon from Kunji Cave gave a radiocarbon date of greater than 40,000 years (Hole and Flannery, 1967a). While we cannot be certain when the Middle Paleolithic began in Iran, we know that it ended before 30,000 years ago with the appearance of the Baradostian Upper Paleolithic. Much has been made of the distinctive technical characteristics of the stone tools of the Zagros Mousterian (Baumler and Speth, 1993; Dibble and Holdaway, 1993; Skinner, 1965; Smith, 1986), as compared with those of the Levant or Europe. “The main distinctions include the much lower frequencies of Levallois [a technique of flaking the flint (Dibble and Bar-Yosef, 1995)] in the Zagros and an almost total emphasis on double [two-edged] and convergent [two-sided] scraper forms there instead of the transverse [broad-bladed] and déjeté [obliquely angled] forms” (which are found in the Levant; Dibble and Holdaway, 1993, p. 91).

Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan is the most important site in the region (Solecki, 1963) owing to the remains of numerous Neanderthals, some of whom were crushed by rockfalls in this earthquake-prone region. One apparent burial, in sediments containing flower pollen, is the subject of a book (Leroi-Gourhan, 1975; Solecki, 1960 and 1971; Stewart, 1963). The Middle Paleolithic of Shanidar closely resembles that found at Hazer Merd cave near Solaymāniya (Garrod, 1930) and several sites in Iran. No Neanderthal skeletal remains have yet been found in any of the Iranian caves. The best-known sites are Warwasi (Dibble and Holdaway, 1993) and Bisotun (Coon, 1951; Dibble, 1984), near Kermānšāh, and Kunji Cave and Gar Arjeneh (Ḡār-e Arjena) near Ḵorramābād (Baumler and Speth, 1993; Hole and Flannery, 1967a). The cave of Ghar-i Khar (Ḡār-e Ḵar) near Bisotun holds promise of being as important as Shanidar, but it has not yet been fully excavated (Smith 1986, p. 18). Apart from these sites, numerous other similar occurrences are known, but few have seen even small test excavations, and these have simply added similar material (Biglari, 2001; Biglari and Heydari, 2001; Roustaei et al., 2002).

All of the excavated sites have yielded lithics, animal bones, and fireplace ash, but no other types of artifacts, such as might have been made of bone or wood. The Middle Paleolithic occurred during periods of profound climate change, yet there are no indications that habits changed, implying that people occupied these mountain regions only during the warmer periods. The sites inform more on the presence of people and their hunting habits than on other particulars of their life style.

Upper Paleolithic-Baradostian. There was a technological transformation or evolution between the Middle and Upper Paleolithic. Rather than a lithic industry based on flakes, now there is an increasing emphasis on blades (elongate and regularly shaped flakes) and in time a gradual reduction in their size (Hole and Flannery, 1967a; Olszewski, 1993a). More important than the shape of the flakes is that now they are used to make a new array of specialized tools, including scrapers, gravers, and narrow points that were probably hafted on spears or arrows. Significant innovations also include the use of bone for awls, and flat stones for grinding ochre pigments and plant foods. Unlike Europe, here there is no evidence at this time for “art,” although the use of pigments implies deliberate coloring of bodies or artifacts.

The Baradostian is the Zagros variety of the Eurasian Upper Paleolithic. First described by Ralph Solecki (Solecki, 1958), it has subsequently been found in Iran in Warwasi (Olszewski, 1993a), Ghar-i Khar (Smith 1986, p. 27), Gar Arjeneh (Hole and Flannery, 1967a), and Yafteh (Yafta) Cave. Surveys in the Holaylān valley (Smith, 1986, no. 1452; p. 27), Lorestan (Roustaei et al., 2002), and Khuzestan (Wright, 1979) indicate that there are many more small caves and shelters in the central Zagros. Beyond the Zagros there are surface indications of Upper Paleolithic around the now dry playa Lake Tašk in Fārs province (Krinsley, 1970, no. 8314; p. 224). Rosenberg reports finding 24 sites in Marv Dašt, one of which, Eškāft-e Gāvi, has Mousterian as well as early and late Baradostian indications (Rosenberg, 1988: p. 455).Another reported surface occurrence of Upper Paleolithic is at Šekaft-e Ḡad-e Barm-e Šur on Lake Maharlu, near Shiraz (Piperno, 1974). The numerous occurrences of Upper Paleolithic lithics on the plateau as well as in the Zagros implies that the distribution of people was wider and their adaptation more varied than in the Middle Paleolithic.

The excavated sites give few clues to significant differences in adaptation from the Middle Paleolithic, perhaps because the sites are functionally similar— hunting camps rather than residential. On the other hand, the same animals were being hunted, albeit with new and evolving tool types that give the Upper Paleolithic the appearance of being more diverse and specialized.

The latest part of the Upper Paleolithic occurred during the Late Glacial Maximum (LGM), when the mountains were permanently covered with snow, so that one should expect there to be gaps or discontinuities in settlement. Weather during the late Pleistocene was always colder than today, but there were periods when it cycled between moderate and frigid. Neanderthals as well as the Upper Paleolithic people had to adapt to these changes, either through developing efficient shelters or by migrating to warmer places. If they migrated, then the sites we find in Iran must often have been relatively short-term camps of hunters who made only brief forays into the mountains during the warm periods.

One of the questions driving research is to find sites that hold evidence of a transition from Middle to Upper Paleolithic, a question stimulated by an interest in the origins of modern Homo sapiens and the disappearance of Neanderthals. Was there a biological evolution from Neanderthal to modern people, or was there a replacement of Neanderthals? So far, the data in archeological sites have not been adequate to answer this question (Bar-Yosef, 1998; Smith, 1986, p. 25). The actual dates for the duration of the Baradostian are not known, despite radiocarbon determinations from both Yafteh and Shanidar caves. The first series of dates for the early Baradostian from Yafteh Cave, run on carbon, gave an estimate of 32-38,000 years ago (Hole and Flannery, 1967b), but recent analyses on charred bone, using the more accurate AMS (accelerator mass spectrometry) method, determined an age of 30-32,000 years, while bone collagen yielded dates of only 22-23,000 years ago. One might argue for either set of dates as being correct. The older dates correspond well with dates for comparable lithics in the Levant and Europe, and leave less room for a temporal gap between the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, as suggested for Shanidar (Solecki, 1963, p. 188). On the other hand, Warwasi, Ghar-i Khar, and Gar Arjeneh lack any stratigraphic break between Middle and Upper Paleolithic, as one would expect if some 10-20,000 years separated them. Adjusting the Middle Paleolithic forward in time does not seem possible in view of radiocarbon dates of greater than 40,000 years from Kunji Cave.

If the early Baradostian is as late as 22,000, it is in the midst of the LGM, when it seems unlikely that the Zagros supported much human activity (van Zeist and Bottema, 1977). An argument for an even later date for the end of the Baradostian is that it appears to develop into the Zarzian, a final Paleolithic industry. Again, there is no apparent stratigraphic break between the Baradostian and Zarzian at the three sites where it has been excavated and reported.

Terminal Paleolithic-Zarzian. The terminal Paleolithic in western Iran is known as the Zarzian, after the cave of Zarzi in Iraqi Kurdistan (Garrod, 1930). The hallmark of the Zarzian is small blades (microlithics), many of which in the latest Zarzian are chipped into geometric forms such as triangles and trapezoids (Hole and Flannery, 1967b; Wahida, 1981). The reduction in size of tools that started in the early Baradostian reached its climax with the Zarzian, and this change required the development of the single platform core from which the little blades were struck (Hildebrand, 1996).

Radiocarbon dates from Shanidar and Palegawra, also in Iraqi Kurdistan, indicate a Zarzian presence by 17,000 years ago, and it is generally assumed that it lasted until the advent of the Neolithic about 10,000 years ago. This date range would allow for settlement of the Zagros in the millennia after the LGM when conditions improved sufficiently to allow the spread of vegetation back into the higher elevations. This date does, however, imply a considerable gap with the Baradostian, even if we use the latest dates for that industry. Shanidar Cave was abandoned during the LGM, as were sites inIranian Paleolithic northern Afghanistan and Central Asia, and a similar hiatus may have occurred in Iran (Davis and Ranov, 1999; Smith, 1986, p. 28), although stratification in the sites does not show it (Olszewski, 1993b; Hole, 1967, no. 7737).

With climatic amelioration throughout the world following the LGM, there were opportunities for the movement of people out of warmer zones into the mountains, making use of camps outside caves and shelters. The primary Zarzian sites are Ghar-i Khar, Gar Arjeneh, and Pa Sangar, where small bands of hunters observed game on the plain below and brought the meat back to eat. A number of other caves are known in the Holaylān valley, along with open-air sites (Mortensen, 1974a, b, 1975). Situated at a lower elevation, Holaylān may have been a cool or winter season camping area.

Based on scant information from the excavated sites of Pa Sangar, Palegawra, Zarzi, and Shanidar, there was little change in hunting practices from previous periods in that goats and onager were still the main quarry. However, there was an increased emphasis on small game, including partridge and duck, as well as freshwater crabs, clams, turtles, and, for the first time, fish. At both Zarzi and Shanidar excavators found quantities of land snails among the Zarzian debris. Flannery characterized this diversity as the broad spectrum revolution, in which the range of species hunted was greatly expanded from previous periods (Flannery, 1969). Mary Stiner attributes the diversity, in part, to dietary stress, which forced people to collect smaller animals, because the larger ones were no longer available either through over-hunting or environmental changes (Stiner, 1993). In the absence of human skeletons from this period, we cannot assess how humans may have been affected. At Palegawra we have the first indication of domesticated dog (Turnbull 1974). It would be interesting to know whether people were eating much plant food during the Zarzian, presaging an agricultural diet, as occurred in the Levant.

There are few Neolithic artifacts from these sites apart from bone awls. At Pa Sangar, two large saltwater scallop shells lay side by side, and bits of red ochre were also recovered (Hole, 1987).

Beyond the Zagros, lithics attributed to the Epipaleolithic, but not specifically Zarzian, have been reported from a number of places in southern Iran. Lithics at rockshelters on the shore of Lake Maharlu near Shiraz were reported by Henry Field (Field, 1939, p. 445). In the Marv Dasht valley, Rosenberg found a handful of sites with Iranian Paleolithic geometric microliths that he attributes to the Zarzian or a variant of it (Rosenberg, 1988, p. 458). Surveys on the Izeh (Iḏa), Dasht-i Gol (Dašt-e Gol), and Iveh (Iva) plains have also revealed a number of sites with microlithic blades but apparently not geometrics, leaving open whether these are early Neolithic or Zarzian (Smith, 1986, p. 31; Wright, 1979).

Two sites along the southern Caspian coast have stone tools resembling those of the Terminal Paleolithic. The Caspian region, along the Māzandarān plain, was probably attractive to people because of its mild climate and rich resources, but there is no archeological evidence of their presence before the Terminal Paleolithic. Belt (Ḡār-e Kamarband; Coon, 1951, 1952, 1957), and Ali Tappeh (ʿAli Tappa) I (McBurney, 1968) have lithics similar to the Zarzian. During the Pleistocene, the Caspian Sea was at a higher level than today, and Ali Tappeh was just above its shoreline. As the sea receded, Belt and Hotu became accessible and were occupied. People living along the coast took advantage of the resources of the sea, the coastal marshes, and the mountain slopes. The fauna show an interesting change. Early there is a predominance of gazelle and seal, with some ox and deer, but later gazelle predominate, with some goat or sheep (McBurney, 1968). One may speculate that an environmental change led to the shift in diet. These sites give hints of the potential of the region for further exploration and excavation using modern methods.

The Terminal Paleolithic took place during a period of rising temperatures until about 13,000 BCE, when the region suffered a rapid reversal to near glacial conditions (the Younger Dryas period)—a shock that must have decimated many populations. Perhaps because people abandoned the Zagros during this time, there is no site that gives convincing evidence of continuity with the proto-Neolithic cultures that follow. In the eastern Mediterranean, agriculture began just after the Younger Dryas climate had shifted into one even more agreeable than today’s, but it was a thousand years or more before agriculture reached the Zagros (Hole, 1998).

This review has highlighted the dearth of solid information. Iran has immense geographic variability, but our knowledge of the Paleolithic comes largely from the Zagros mountain zone. We need investigations of the plateau and desert regions, especially around the playa lakes that formed during wetter periods. The southern coast, with its potential for a maritime adaptation focused on sea mammals and fish holds much Iranian Paleolithic promise for all periods. We also need accurate determinations of ages using modern techniques, and finally we need an accurate assessment of climate changes and their effects on the humans and other species. With new focused field research, Iran holds the promise of yielding substantial new discoveries of all periods.

Bibliography:

A. Ariai and C. Thibauld, “Nouvelles précisions а propos de l’outillage pakolithique ancien sur galets du Khorassan (Iran),” Paléorient 3, 1975-77, pp. 101-8.

O. Bar-Yosef, “On the Nature of Transitions: The Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution,” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 8, 1998, pp. 141-63.

M. F. Baumler and J. D. Speth, “A Middle Paleolithic Assemblage from Kunji Cave, Iran,” in Olszewski and Dibble, eds., 1993, pp. 1-74.

F. Biglari, “Recent Finds of Paleolithic Period from Bisitun, Central Western Zagros Mountains (in Persian with English abstract),” Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History 28, 2001, pp. 50-60.

F. Biglari and S. Heydari, “Do-Ashkaft: a Recently Discovered Mousterian Cave Site in the Kermanshah Plain, Iran,” Antiquity 75, 2001, pp. 487-88.

F. Biglari, G. Nokandeh, and S. Heydari, “A Recent Find of a Possible Lower Palaeolithic Assemblage from the Foothills of the Zagros Mountains,” Antiquity 174, 2000, pp. 749-50.

R. J. Braidwood, “Seeking the World’s First Farmers in Persian Kurdistan,” Illustrated London News 237, 1960, pp. 695-97.

R. J. Braidwood and B. Howe, Prehistoric Investigations in Iraqi Kurdistan, Chicago, 1960.

C. S. Coon, Cave Explorations in Iran 1949,Museum Monographs, Philadelphia, 1951.

Idem, “Excavations in Hotu Cave, Iran, 1951.

A Preliminary Report (with sections on the artifacts by L. B. Dupree and the human skeletal remains by J. L. Angel),” in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96, 1952, pp. 231-69.

Idem, The Seven Caves. Archaeological Explorations in the Middle East, New York, 1957.

R. S. David and V. A. Ranov, “Recent Work on the Paleolithic of Central Asia,” Evolutionary Anthropology 8, 1999, pp. 186-93.

H. L. Dibble, “The Mousterian Industry from Bisitun Cave (Iran),” Pakorient 18, 1984, pp. 23-34.

H. L. Dibble and O. Bar-Yosef, The Definition and Interpretation of Levallois Technology,Madison, Wis., 1995.

H. L. Dibble and S. J. Holdaway, “The Middle Paleolithic Industries of Warwasi,” The Paleolithic Prehistory of the Zagros-Taurus,in Olszewski and Dibble, eds., 1993, pp. 75-100.

L. Dupree and R. S. Davis, “The Lithic and Bone Specimens from Aq Kupruk and Darra-i-Kur,” in Prehistoric Research in Afghanistan (1959-1966), ed. L. Dupree, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 62, pt. 4, Philadelphia, 1972, pp. 14-32.

H. Field, Contributions to the Anthropology of Iran, Field Museum of Natural History, Anthropological Series29, 2 vols., Chicago, 1939.

K. V. Flannery, “Origins and Ecological Effects of Early Domestication in Iran and the Near East,” in The Domestication of Plants and Animals,ed. Peter J. Ucko, London, 1969, pp. 73-100.

D. A. E. Garrod, “The Palaeolithic of Southern Kurdistan: Excavations in the Caves of Iranian Paleolithic Zarzi and Hazar Merd,” Bulletin of the American School of Prehistoric Research 6, 1930, pp. 8-43.

J. Gowlett, “Tools - The Palaeolithic Record,” in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, ed. Steve Jones, Robert Martin, and David Pilbeam, Cambridge, 1992, pp. 350-60.

E. Hildebrand, “Changes in Methods and Techniques of Blade Production During the Epipalaeolithic and Early Neolithic in the Eastern Fertile Crescent,” in Neolithic Chipped Stone Industries of the Fertile Crescent, and Their Contemporaries in Adjacent Regions, Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence, and Environment3, ed. S. K. Kozlowski and H. G. K. Gebel, Berlin, 1996, pp. 193-206.

F. Hole, The Archaeology of Western Iran, Washington, D.C., 1987.

Idem, “The Spread of Agriculture to the Eastern Arc of the Fertile Crescent: Food for the Herders,” in The Origins of Agriculture and Crop Domestication. The Harland Symposium, ed. A. B. Damania et al., Aleppo, Syria, 1998, pp. 83-92.

F. Hole and K. V. Flannery, “The Prehistory of Southwestern Iran: a Preliminary Report,” Proceedings of the Prehistory Society 33, 1967, pp. 147-206.

G. W. Hume, The Ladizian: an Industry of the Asian Chopper-Chopping Tool Complex in Iranian Baluchistan, Philadelphia, 1976.

A. Leroi-Gourhan, “The Flowers Found with Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Burial in Iraq,” Science 190, 1975, pp. 562-64.

C. B. M. McBurney, “The Cave of Ali Tappeh and the Epi-Palaeolithic in N. E. Iran,” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 34, 1968, pp. 385-411.

A. Minzoni-Deroche, “Middle and Upper Paleolithic in the Taurus-Zagros Region,” in Olszewski and Dibble, eds., 1993, pp. 147-58.

P. Mortensen, “A Survey of Early Prehistoric Sites in the Holailan Valley in Lorestan,” Proceedings of the Second Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, Tehran, 1974, pp. 34-52.

Idem, “A Survey of Prehistoric Settlements in Northern Luristan,” Acta Archaeologica 45, 1974, pp. 1-47.

Idem, “Survey and Soundings in the Holailan Valley 1974,” in Proceedings of the IIIrd Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, Tehran, 1975, pp. 1-12.

H. L. Movius, Jr., “The Mousterian Cave of Teshik-Tash, Southeastern Uzbekistan, Central Asia,” Bulletin, American School of Prehistoric Research 17, 1953, pp. 11-71.

H. L. Movius, “Lower Paleolithic archaeology in Southern Asia and the Far East,” in Early Man in the Far East, ed. W. L. Howells, New York, 1969, pp. 17-81.

D. I. Olszewski, “The Late Baradostian Occupation at Warwasi Rockshelter, Iran,” in Olszewski and Dibble, eds., 1993, pp. 187-206.

Idem, “The Zarzian Occupation at Warwasi Rockshelter, Iran,” in Olszewski and Dibble, eds., 1993, pp. 207-36.

Idem and Harold L. Dibble, eds., The Paleolithic Prehistory of the Zagros-Taurus, Philadelphia, 1993.

M. Piperno, “Upper Palaeolithic Caves in Southern Iran: Preliminary Report,” East and West 24, 1974, pp. 9-13.

M. Rosenberg, “Paleolithic Settlement Patterns in the Marv Dasht, Fars Province, Iran,” Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1988.

K. Roustaei, F. Biglari, S. Heydari, and H. Vahdati, “Recent Research on the Paleolithic of Lurestan, West Central Iran,” Antiquity 76, 2002, pp. 19-20.

H. Sadek-Kooros, “Palaeolithic Cultures in Iran,” in Proceedings of the IInd Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, Tehran, ed. F. Bagherzadeh, Tehran, 1974, pp. 53-65.

Idem, “Early Hominid Traces in East Azerbaijan,” in Proceedings of the IVth Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran,ed. F. Bagherzadeh, Tehran, 1976, pp. 1-10.

J. Skinner, “The Flake Industries of Southwest Asia: A Typological Study,” Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1965.

P. E. L. Smith, Palaeolithic Archaeology in Iran, Philadelphia, 1986.

R. S. Solecki, “The Baradostian Industry and the Upper Paleolithic in the Near East,” Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1958.

Idem, “Three Adult Neanderthal Skeletons from Shanidar Cave, Northern Iraq,” in Smithsonian Report for 1959 (Publication 4414), Washington, D.C., 1960, pp. 603-35.

Idem, Shanidar: The First Flower People, New York, 1971.

T. D. Stewart, “Shanidar Skeletons IV and VI,” Sumer 19, 1963, pp. 8-26.

M. C. Stiner, “Small Animal Exploitation and its Relation to Hunting, Scavenging, and Gathering in the Italian Mousterian,” in Hunting and Animal Exploitation in the Later Palaeolithic and Mesolithic of Eurasia, Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 4, ed. G. L. Peterkin, H. M. Bricker, and P. Mellars, Washington, D.C., 1993, pp. 107-26.

P. F. Turnbull and C. A. Reed, “The Fauna from the Terminal Pleistocene of Palegawra Cave, a Zarzian Occupation Site in Northeastern Iraq,” Fieldiana: Anthropology 63, 1974, pp. 81-146.

W. van Zeist and S. Bottema, “Palynological Investigations in Western Iran,” Palaeohistoria 19, 1977, pp. 19-85.

G. Wahida, “The Re-Excavation of Zarzi,” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 47, 1981, pp. 19-40.

July 28, 2008

(Frank Hole)

Originally Published: July 28, 2008