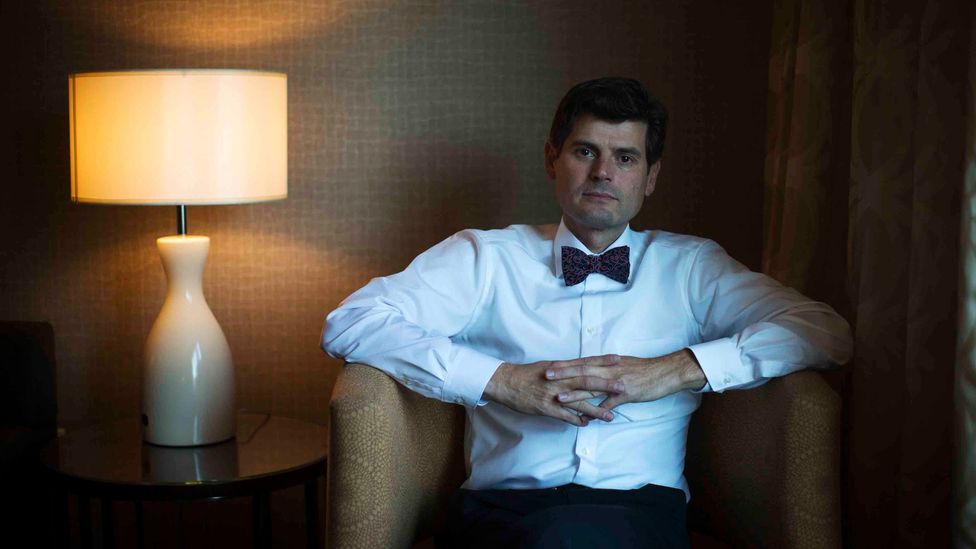

Tariq Ali

Notebooks: 1936-47 by Victor Serge

translated by Mitchell Abidor and Richard Greeman.

NYRB, 651 pp., £17.99, April 2019, 978 1 68137 270 9

Mexico city, 6 July 1946. Victor Serge had a year to live. He had spent the morning, as he sometimes did, with Trotsky’s widow, Natalia Sedova. They had been writing a joint memoir of Trotsky; in it Natalia recalls her husband pacing up and down in his study at Coyoacán, engaged in heated imaginary conversation with old dead Bolsheviks, arguing about Stalin, and how and why they had been defeated by him. Serge noted that Sedova wasn’t looking well:

What gnaws at her in reality is an immense bereavement, infinitely greater than that of Lev Davidovich, which only finished her off. It is grief for an era and an uncountable crowd. And since I’m probably the only person to truly share this with her, our discussions are precious to us, but I nevertheless avoid touching on the numberless dead. Despite us, they rise up: the tomb of a generation is always present. This time ... we recalled Osip Emilievich Mandelstam, who died in prison.

Serge also recalls an evening in Moscow around 1930, when Mandelstam had seemed nervous and uneasy. Serge asked him what was wrong. Mandelstam replied: ‘It’s that you’re a Marxist.’ Serge understood. ‘When I showed him a volume of photos of Paris by night, the strain between us quickly evaporated.’ On another occasion, he ‘stupidly attempted to commit suicide by throwing himself out of too low a window’. In 1935, the year before Serge was expelled from the Soviet Union, Mandelstam jotted down a few satirical lines about how all of them, ‘unpersons’ by this point, might be remembered:

NYRB, 651 pp., £17.99, April 2019, 978 1 68137 270 9

Mexico city, 6 July 1946. Victor Serge had a year to live. He had spent the morning, as he sometimes did, with Trotsky’s widow, Natalia Sedova. They had been writing a joint memoir of Trotsky; in it Natalia recalls her husband pacing up and down in his study at Coyoacán, engaged in heated imaginary conversation with old dead Bolsheviks, arguing about Stalin, and how and why they had been defeated by him. Serge noted that Sedova wasn’t looking well:

What gnaws at her in reality is an immense bereavement, infinitely greater than that of Lev Davidovich, which only finished her off. It is grief for an era and an uncountable crowd. And since I’m probably the only person to truly share this with her, our discussions are precious to us, but I nevertheless avoid touching on the numberless dead. Despite us, they rise up: the tomb of a generation is always present. This time ... we recalled Osip Emilievich Mandelstam, who died in prison.

Serge also recalls an evening in Moscow around 1930, when Mandelstam had seemed nervous and uneasy. Serge asked him what was wrong. Mandelstam replied: ‘It’s that you’re a Marxist.’ Serge understood. ‘When I showed him a volume of photos of Paris by night, the strain between us quickly evaporated.’ On another occasion, he ‘stupidly attempted to commit suicide by throwing himself out of too low a window’. In 1935, the year before Serge was expelled from the Soviet Union, Mandelstam jotted down a few satirical lines about how all of them, ‘unpersons’ by this point, might be remembered:

What street’s this one?

– ‘This is Mandelstam Street.

His disposition wasn’t “party-line”

Or “sweet as a flower”.

That’s why this street –

Or, rather, sewer

Or possibly slum –

Has been named after

Osip Mandelstam.’

As a writer Serge has often been compared – foolishly, I think – to Koestler, Silone, Orwell, Camus. But he’s so much better. Liberalism, despite a few clumsy attempts, has not been able to appropriate him. Serge knew better than most how to interpret and record the hopes, fears and defeats that marked a political life dedicated to resistance and revolution. His life spanned the First World War, the Russian Revolution and its aftermath, the triumph and defeat of Mussolini and Hitler, the rise of Franco. These Notebooks, which include some recently discovered material, cover the last decade of his life.

Much has been written about Serge’s life, first and foremost in his own Memoirs of a Revolutionary. Susan Weissman provided a meticulous account in Victor Serge: A Political Biography, published in 2001. Born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich in Brussels in 1890, Serge was the son of poverty-stricken intellectuals who had fled tsarist Russia. The family name itself was suspect. One of his relatives, Nikolai Kibalchich, a chemist by training, had built the bomb that killed Alexander II in 1881. Along with other members of the underground anarchist group which had planned and carried out the assassination – including Sophia Perovskaya, whose father, the governor general of St Petersburg, was responsible for the tsar’s travel and security arrangements – Kibalchich was hanged. But he was celebrated after the revolution and commemorated as a rocket pioneer on Soviet stamps of the 1960s.

In his late teens, Serge, like Kibalchich, was attracted to radical anarchism. After moving to Paris, he joined the Bonnot Gang, a courageous but nutty group intent on committing violent acts, including bank robberies. After one confrontation, Serge was arrested, taken to the prison of La Santé and made an offer. If he gave an account of the group’s leaders he would be rewarded and released. He refused, and was given a five-year prison sentence for conspiracy. On his release in 1917 he went to Barcelona, which is where he was when the news came of revolution in Russia. In Spain, factory workers and trade unionists rejoiced, and a Workers’ Committee was set up to prepare for a revolutionary general strike. Serge noted that in France too an ‘intensely alive electric current was crossing from the trenches to the factories, the same violent hopes were coming to birth’. Militias were organised by workers in Barcelona and unions opened discussions with the Catalan liberal bourgeoisie, with the aim of getting rid of the monarchy – but the movement, isolated geographically and politically, was defeated.

Serge decided it was time for a visit to his ancestral homeland. It wasn’t easy: it took him a year and a half. First, he went back to Paris, where he visited the Russian military HQ on the avenue Rapp, whose officers were now all ‘good republicans’. They were polite, but couldn’t help him. Soldiers from the Russian Expeditionary Force based at the military camp of La Courtine had demanded immediate repatriation to Russia, but the French refused to allow it – and the soldiers mutinied, only to be crushed by French artillery fire. Serge was eventually sent to Russia as part of a prisoner exchange, and arrived in Petrograd in January 1919. Hunger and typhus gripped the city. When he went to the party headquarters to join up, the local commissar for foreign affairs asked: ‘What are they saying about us abroad?’ ‘They’re saying that Bolshevism equals banditry,’ Serge said. ‘There’s something in that,’ the commissar replied. ‘You’ll see for yourself.’ Serge’s Year One of the Russian Revolution conveys the mood of this period brilliantly. Hope and despair mingle in its pages.Revolutionary movements depend on hope. When they’re successful, their supporters can see the path to liberation and happiness, a glimpse of the imagined future. But the transition to that future, always difficult and far removed from these ideals, poses serious problems for many revolutionaries. Some of them despair and sink into political apathy, moral indifference, navel-gazing. A minority continue to insist that if the means bear little or no relationship to the ends, the means will become the ends. They write or say this in public and are silenced or punished for it. Serge belonged to this group. He refused to put down his pen or moderate his opinions. He was lucky that it didn’t cost him his life. For most of the 1920s Serge worked for the Comintern, his Soviet passport of the civil war period describing him as ‘General Staff/Red Army’, and he wrote in support of Lenin’s complaints about the growing bureaucratisation of the party and the ‘Great Russian chauvinism’ that sidelined Georgia and other nations.

After Lenin’s death, he became a supporter of the Trotsky-led Left Opposition, and in 1933 was sent into internal exile in Orenburg, near the Kazakh border. L’Affaire Victor Serge caused a scandal in Paris, where he was known to the French left as a great defender of the Soviet Union. André Gide interceded on his behalf and Romain Rolland spoke directly to Stalin, who released Serge in 1936, authorising his expulsion from the Soviet Union. Serge, along with his first wife and children, went into exile again, first to Belgium and then to France. The NKVD gave him a receipt for the manuscript they confiscated, a book about prewar France to be called ‘Les Hommes perdus’, but all attempts to track it down during the Gorbachev and Yeltsin periods failed. He had never again, Serge said, had time to reread and edit his writing. The other books were rushed, written in instalments with Stendhalian energy, and sent to far-off publishers.

Many of his comrades were exterminated following the show trials, which he later called the ‘midnight of the century’. What shook Serge and Trotsky, with whom he began to correspond after his expulsion, were the ‘confessions’, which appropriated the language and methods of the Spanish Inquisition. Zinoviev, one of Lenin’s closest comrades, with whom Serge had worked at the Comintern in the early 1920s, ‘confessed’ thus: ‘My defective Bolshevism became transformed into anti-Bolshevism, and through Trotskyism I arrived at fascism. Trotskyism is a variety of fascism and Zinovievism is a variety of Trotskyism.’ (The inquisitors of the 18th century were better writers. Compare: ‘I am a satellite and disciple of Satan. For a long time I was a porter at the gate of hell, but several years ago, with 11 of my companions, I began to lay waste the kingdom of the Franks. As we were ordered, we destroyed the corn, the wine and all the other fruits produced by the earth for the use of man.’) One of the few non-communists to defend the trials was Joseph Davies, the US ambassador to the Soviet Union, who claimed to find the confessions persuasive. Serge regarded them as a consequence of the insistence that party decisions had to be supported whether ‘right or wrong’. For him, the result was an ‘abdication of consciences in the face of a party that had lost its soul’.Many of the survivors of the Bolshevik movement, tired and forlorn, resigned themselves to passive support of the measures taken by Stalin, even when they were irrational and unjustifiable. European fascism was seen as the main enemy. Had Trotsky not warned endlessly in 1931-32 that the birth of fascism and the growing support for it in Germany necessitated a united front of all anti-fascists, especially communists and social democrats? (Later, in December 1938, Trotsky predicted what would follow: ‘It is possible to imagine without difficulty what awaits the Jews at the mere outbreak of the future world war. But even without war the next development of world reaction signifies with certainty the physical extermination of the Jews.’) Serge agreed that fascism had to be defeated however high the cost, but he parted company with many others on the left (Brecht, Benjamin et al) when they insisted that a political truce with Stalin was necessary if that battle was to be won. For Serge this was impossible. Within weeks of his arrival in the West in 1936, he began writing articles and pamphlets denouncing the Moscow trials. Alas, at the time of the Popular Front in France, criticism of Stalin was taboo. Most of Serge’s exposés, based on intimate knowledge of the defendants, were unpublishable, and he was forced to earn his living as a proofreader for the same socialist newspapers that rejected his articles.

Trotsky remained his mentor and friend. Serge loved him despite all their disagreements and translated his essays into French with great enthusiasm and care, improving them along the way. Serge remembers Trotsky hopping off his armoured train during a brief stopover in Moscow in the early 1920s, rushing straight to the translation office of the Comintern, and depositing a hurriedly knocked off 300-page ‘pamphlet’ on Serge’s desk. ‘Must be translated quickly. My response to the slanders of the German social democracy.’ Title? ‘Terrorism and Communism.’ Serge recognised very early that, no matter where Trotsky’s journey ended, he would never become a person of the type mocked by Hegel, someone who would collapse and ‘fall like empty husks’ once his ‘mission in history’ was over. Serge himself was no different.

Stalin’s agents, led by the ever reliable NKVD killer Leonid Eitingon, finally caught up with Trotsky in Mexico City in August 1940. By then, Germany had invaded France and Serge was trying to leave the country. He and his son managed to get places on the last boat to leave Marseille. The long, exhausting sea journey that ended, months later, in Mexico City provided ample time for writing. The Notebooks contain vivid descriptions of the coastline as the freighter full of refugees skirted the North African coast and headed in the direction of Martinique. André Breton was on board; so was Claude Lévi-Strauss. Both were wonderful raconteurs. There are caustic pen portraits of French and Soviet writers and politicians, and descriptions of other passengers. The forward section is ‘densely populated but maintains a chic tone because of a group of filmmakers and well-dressed emigrants with cash who put on airs as if they were at a café on the Left Bank’; the Bretons and Lams lounge on the upper deck, as Jacqueline Lamba, Breton’s wife, ‘sunbathes almost completely nude and scorns the universe which, by ignoring her, vexes her’. Dr S, a French colon and member of the Tunisian Grand Council, is anxious to show Serge something hidden in his cabin:

He unveils a small painting, in fact quite lovely, a recumbent woman dressed in warm blues: it’s a Manet, the portrait of the painter’s wife, dated 1873, bought in Algiers second-hand for ‘five hundred francs, can you imagine!’ Five hundred francs, five thousand, or five million, I don’t give a damn, but to save a painting, to take joy in this, to save a moment of its soul at the moment when the great ship ‘Civilisation’ risks sinking to the bottom with all its Sistines and its Curie laboratories is good, Doctor, is splendid! We drink a glass of cognac – almost friends.

There are interesting conversations with a cultured Viennese bourgeois, who introduces himself as a banker and is on his way to a new life in Brazil. He looks at Serge expectantly. ‘I’m a friend of Mr Trotsky,’ Serge says. To his amusement, the banker tries to conceal his disappointment.

Serge arrived in Mexico City a year or so after Trotsky’s assassination. Observing the war from his remote exile, he wrote in his Notebooks on the anniversary of the revolution: ‘Gloomy anniversary of October. Leningrad and Moscow besieged, Rostov lost, Crimea invaded. How distant am I, despite myself, from the Russian nightmare. And for the first time, I try to imagine it as in some way abstract. Otherwise it would be intolerable.’ Serge himself was soon under attack. As his Notebooks show, the local press, by then under Russian influence, refused to publish his pieces, and a meeting at which he attempted to speak was attacked by Communist Party goons and one of his friends badly injured.

On 15 May 1946, a year before his death, he suffered what may have been a mild heart attack. ‘I was suddenly seized by one of those oppressive dizzy spells that have been striking me very frequently of late, and which weaken me to a distressing extent,’ he wrote in his Notebooks. ‘My heart starts to beat strongly and unevenly, a psychological anxiety ... in the upper chest, more to the left it seems to me, and when it’s really bad I feel such a buzzing vertigo mounting to my head that I fear falling, that remaining upright is becoming impossible.’ He goes on:

The idea of the proximity of death, appearing more clearly than in other recent similar circumstances, causes me no fright, no fear, and isn’t even a real hindrance in my daily activities. The hindrance is physical and great: I am afraid of wandering at random, not knowing whether the dizziness will appear unexpectedly. I feel myself to be in a state of readiness, ready to leave, to disappear simply. Not without effort, I tried to attain and thought I had attained this state of calm readiness at the internal prison of the GPU in Moscow in 1933, when I envisioned my execution. Today I think that at the time I believed I had attained it more than I attained it in truth, and I succeeded in achieving a calm more apparent, more superficial than profound.

Now, whether from the wearing down of life or from a more assured serenity (with its deep-down dose of despair), my readiness is more sure. Enough, in any case, that I do not feel any obsessive anxiety and have not lost the taste for anything I love: those close to me, life, ideas and work ...

A sensual attachment to life, even in its details, its dailiness, a ceaseless curiosity about the earth and ideas.

The wish to see better days, or at least the beginning of better days.

The frustration at being interrupted in the middle of my activity, with a matured mind, a personality filled with detritus but somewhat purified. The disagreeableness of not holding out until some form of victory in the long combat.

Despite personal setbacks and political defeats, Serge never renounced or denounced the revolution. In her introduction to a reissue of his finest novel, The Case of Comrade Tulayev, Susan Sontag tried to enlist him in the ranks of ‘anti-communists’. Whatever else, he was never that. He defended the historical validity of the Russian Revolution until the end of his life; he accepted that the ‘germs of Stalinism’ were present from the start, but insisted that there were ‘many other germs as well’. His painter son, Vlady Kibalchich, whom I met a number of times in Mexico City and who was very close to his father, was firm on this point. Serge was a heretic who remained on the left, never a Cold War renegade who sang the virtues of capitalism or colonialism. Had he done so, many avenues would have opened up for him in the West. His books would have been published and liberal magazines would have competed to get hold of his essays. There would have been no shortage of funds. He might have lived longer. As it was, he was largely dependent on handouts from fans in New York, where Dwight and Nancy Macdonald were especially generous despite their differences.

Serge died in a taxi in Mexico City on the way to see his son. He was 56. His jacket was frayed. His shoes had holes in them. His unidentified body was lying on a slab in the police station where his son found him. He had left a poem:

A night filled with stars, a darkness filled with you:

So that I could love you I had to understand this world

And before I could understand the world, I had to love you.

In his writing, Serge dealt with the street tumults and upheavals of his own time and place, at times excited and inspired, at others repelled by the loud march of history. He was a chronicler and analyst of defeats, of historical regression and its causes, of the fearful shadows of unfettered power. The Notebooks are a treasure chest. The form itself is peculiarly (if not exclusively) French, even if the two most famous examples were written in German and Italian. Marx’s Grundrisse, seven notebooks of self-clarifications developing his ideas and earlier work, was posthumously published in Moscow in 1939 and 1941. Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, written in an Italian fascist prison between 1929 and 1935, contain essays on the state, civil society, the role of intellectuals, Fordism, Italian history and more. Written in an elliptical style to deceive the prison censors, they had a huge influence on political and cultural debates on almost every continent in the mid-20th century. These were exceptions. In most notebooks, elements of a personal diary are present, if not dominant, and such carnets may be intended for publication. Reflections on history, art, philosophy, literature, politics and sexuality are not uncommon. In Serge’s case there is an additional element: a summary of a life foretold, a warning to future generations (don’t repeat our mistakes), a last will and testament. A balance sheet.

More than half the contents of the new edition were first published in 1952 by Julliard. For unknown reasons, Serge’s widow, Laurette Séjourné, insisted that no unpublished material existed. I asked Richard Greeman, his principal translator and founder of the Victor Serge Foundation, what the story was. Séjourné, he explained,had them in her possession but kept them hidden. She denied this to me, to Susan Weissman and even to Serge’s daughter, Jeannine, when directly asked if she had any papers of Serge’s. However, after her death they ended up in her personal archive, where somebody noticed them and brought them to the attention of [the Mexican academic] Claudio Albertani (to whom Laurette also denied having any Serge papers), and he was able to photocopy them and eventually publish a complete French version of the Carnets.

When Weissman finally managed to interview her, Séjourné said: ‘Why do you want to write his biography? He was nothing.’

Rereading The Case of Comrade Tulayev, written during Serge’s time in Mexico, I was reminded of Eisenstein’s imagery in Ivan the Terrible – the novel has much to teach us in these bad times. It tells the story of the Soviet purges, starting with the assassination of Sergei Kirov in Leningrad. An apolitical citizen with a revolver kills a senior party official. Others pay the price: men and women of Serge’s political generation, some of whom were his friends and relations. He returned to this theme in his last novel, Unforgiving Years, a bleak, pessimistic, lyrical, frightening book, devoid of hope. Set during the Second World War, it was first published in France in 1971 and then in English in 2008 by NYRB Classics, which is gradually publishing Serge’s complete works. The two need to be read in tandem. Many of the characters in the later novel are dazed and demoralised Soviet intelligence agents in Paris. One of them is based on a real-life agent codenamed Ludwig, Ignace Reiss, who said that ‘in times like these it is easier to die than to live.’

When I read The Case of Comrade Tulayev for the first time, in the 1970s, I was struck by Serge’s surprisingly realist, if not sympathetic, assessment of Stalin. In the Notebooks, there is an explanation of sorts, given in answer to a question posed by the French-Polish novelist Jean Malaquais: ‘And Stalin, you think, wasn’t a traitor? To have massacred Lenin’s party, made the Russian Revolution what it’s become, is that not treason?’ Serge replies:

In polemical terms, perhaps ... But I don’t like polemical terms that do violence to the truth. In my blocked novel I think I presented an accurate psychological portrait of Stalin. He didn’t break faith, he changed, and history marched on: he bears the heavy burden of a mediocre and powerful personality. He believes in his mission: he sees himself as the saviour of a revolution threatened by ideologues, the idealistic and the unrealistic (recall Napoleon’s contempt for the ideologues). He fought them as he could, with his inferiority complex, his jealousies, his terror of men superior to him and whom he couldn’t understand. He cast them from his saviour’s path by the only methods he had at his disposal: terror and lies, the methods of a limited intelligence governed by suspicion and placed at the service of an immense vitality.

He made himself and circumstances made him the leader, the symbolic figure of a vast new formation of parvenus of the revolution; headstrong, tough, unscrupulous, clutching on to power, living in fear and panic and claiming to embody the victorious revolution. In reality, they incarnated a new phenomenon that socialist theory never predicted: the totalitarian economic state, one of too weak a culture to allow individual freedom, and thus fated for state-directed thought. Directed thought means at one and the same time absolute confidence in oneself, material confidence, and fear of oneself, awareness of one’s own weakness.Isaac Deutscher, with whom Serge should be but never is compared, held a similar view (as did Sartre, whose Les Temps modernes published a selection of the Notebooks after the war). Deutscher, though, went further. A generation younger than Serge, he was born in Chrzanó in 1907 to a strongly rabbinical household. He joined the Polish Communist Party around 1927, but was horrified by the ultra-sectarian position on fascism espoused by Stalin and won over by Trotsky’s writings on how it should be combated. After being expelled by the Polish CP he became involved with Polish supporters of the Left Opposition. When Trotsky decided to found a Fourth International both Serge and Deutscher were opposed, feeling the timing was wrong. Serge predicted it would lead to a proliferation of squabbling sects, and the Polish delegation to the Founding Conference outside Paris in 1938 read out a statement by Deutscher arguing that in forming the Fourth International the Trotskyists would be isolated from currents inside the communist parties in their own countries. Deutscher moved to London, where he began to write in flawless English, often compared to Conrad’s. In a country without a strong communist party posing a real political threat, Deutscher was able to get a temporary job at the Economist and later wrote for the Observer – even if Isaiah Berlin made sure he was denied a teaching post at Sussex. Serge didn’t have his luck.

Curiously, Deutscher’s magisterial three-volume biography of Trotsky doesn’t mention The Life and Death of Leon Trotsky, which Serge wrote with Natalia Sedova. Of the two men, Deutscher, who died in 1967, was always more aware of the contradictions and weaknesses of Stalinism, while Serge tended to overestimate its hold. It was clear that Soviet expansion into Eastern Europe would even in the medium term weaken the system, inside and outside the Soviet Union. The workers’ uprising in East Berlin in 1953, the Hungarian revolt in 1956, the Polish demonstrations in December that same year and finally the crushing of the Prague Spring in August 1968 marked the end of all hope. Asked when he had decided the system was beyond reform, Solzhenitsyn said: ‘On 21 August 1968.’ He was wrong, but he wasn’t the only one. It was difficult then to imagine Gorbachev, let alone the dismantling of the whole system.

Revolutions elsewhere would never lead to carbon copies of Stalin’s Russia, Deutscher argued, but would accelerate the process of reform in the USSR. Stalin’s 1948 excommunication of Tito, who refused to subordinate the Yugoslav revolution to Moscow’s needs, and Khrushchev’s 1958 breach with Mao, vindicated this analysis. The Twentieth Party Congress in 1956, at which Khrushchev denounced Stalin’s crimes, was followed by a decree ordering the closure of the prison camps. By the time ex-communists took anti-communism as their creed, the Gulag had been gone for almost two decades. When the Soviet Union finally collapsed it was the result of an implosion at the top. The bastard offspring of this process is Putin, in whose muscled and well-oiled figure Father Church embraces and violates Mother Russia. Serge and Deutscher would have had a few things to say about this.