GREEN CAPITALI$M

The missing 45%: The role of circularity within climate disclosure

There needs to be more consistency when it comes to how circularity metrics are expressed as part of corporate climate disclosures. Image via Shutterstock

ESG disclosure is rising in priority among corporate sustainability agendas — just look at the number of jobs available on LinkedIn. Simultaneously, it’s becoming more well-known that transitioning to a circular economy — pursuing economic activities that minimize waste and regenerate nature — is critical in eliminating the 45 percent of emissions that arise from how products are made, used and discarded. What is lacking is standardized measurement and disclosure about how companies are using circular initiatives to combat the impacts of climate change.

For each company pursuing circular strategies, the vocabulary differs. A closer evaluation of companies’ public reporting around their circularity efforts shows that how companies strategize for circularity, measure progress and report on the impact delivered is ad hoc and inconsistent. Research shows that companies’ definitions of what makes a "circular economy" varies significantly: Phillips sees a circular economy as keeping products, parts, and materials at their highest utility and value as they circulate between customers, while its competitor LG describes a circular economy as "eco-friendly social contribution programs aimed at establishing a healthy future."

The result? Conflicting and incomparable data about measurable circularity progress. With companies largely determining their own metrics and successes, achieving circularity becomes a self-serving effort. Any disclosure towards this end would fail to capture accurate circularity-related risks and opportunities facing companies.

When we think about optimizing the role of corporate environmental disclosure, we turn to the acronym soup of ESG standards and frameworks. Do ESG scores effectively measure climate progress? Likely not. But they do accelerate environmental data collection, a crucial first step in decarbonizing our economies. However, a survey of leading ESG reporting standards and organizations shows that circular economy topics rarely make an appearance in the questionnaires, frameworks or guidance of such organizations.

Let’s take corporate reports to CDP as an example. Companies can use their CDP disclosure to convey how circularity fits within their climate-related risks and opportunities, Scope 3 calculation approaches and supply chain engagement strategies, while aiming to tie such disclosure to business priorities. But the method in which they do differs. Considering Scope 3 disclosures, for instance, companies’ emissions calculations approaches vary from conducting life-cycle assessments, multiplying product weight by emissions factors or citing estimations based on scientific literature or independent calculations.

Managing and recapturing waste is a critical component of circularity strategies. But "waste" within CDP Scope 3 disclosure, even among similar companies, could imply anything from discarded paper to hazardous materials, and rarely do companies clarify these classifications.

How do you hold companies accountable for tackling those 45 percent of emissions related to making and disposing products, if there is no comprehensive guidance on what is expected of them?

As the space of ESG disclosure evolves, circularity should move away from being an aspiration listed on the company’s website to being a core framework for measuring its comprehensive climate progress.

The focus of reporting organizations such as CDP has been to encourage companies to provide transparency around a set of key environmental metrics, while allowing them the flexibility to also report on environmental topics relevant to them. But most reporting organizations do not yet encourage companies to consider the relevance or materiality of a circular economy to their business model. Nor do they require clarity about how companies’ circularity initiatives tie to their emissions reduction targets, overarching environmental goals or business priorities.

CDP acknowledges the role of "circular thinking" in addressing the climate crisis within its 2021-25 strategy, but given the spikes in interest around circularity, that strategy seems out of sync.

Beyond reporting organizations, measuring corporate performance on circularity has drawn interest from several circularity-related nonprofits and those within academia. Yet, research has shown that there are currently no uniform or scalable approaches from nonprofits in the circularity space that support or encourage the inclusion of circularity information within ESG disclosure.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s (EMF) tools — Circulytics and Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) — are among the leading options available to companies that offer a company-level assessment on circularity progress. However, there is no guidance or incentive for companies to publicly disclose on the assessment they receive from EMF or on the corresponding measures the company is taking to improve its performance.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development’s Circular Transition Indicators (CTI) provides companies with a framework for decision-making around circularity as well as identifying strategies in communicating with stakeholders and value chain partners. While WBCSD’s work is the most far-reaching effort so far, the framework and the self-assessment tool largely target companies receiving inquiries from value chain partners. Therefore, a limited number of companies see an incentive to incorporate the framework within their external reporting strategies.

Yes, a lot of companies use their independent sustainability reports to outline their approach and progress towards circularity, and many might do so consistently each year. So, credit where credit’s due. However, a closer look at these reports shows that there is minimal commentary about the decision-making that went into picking a company’s circularity initiatives. How was it decided which products should be kept "in the loop" vs. phased out? Is landfilling being completely avoided or simply delayed?

Questions such as these are important because researchers have observed that increasing material circularity doesn’t necessarily lead to decreasing environmental impact, as it could shift emissions and create new hotspots that could lead to large shifts of the environmental burden instead of mitigating it. Rarely do companies’ sustainability reports touch on addressing such rebound effects of circularity initiatives.

Additionally, creating a circular economy means more than ensuring products are recyclable. Creating a circular economy also means redesigning products to eliminate waste, transitioning to innovative business models focused on reuse, creating better jobs and preventing biodiversity loss. Reporting only on how recyclable a company’s products are is a missed opportunity for showcasing the widespread benefits of circular initiatives to a business.

Each player in the reporting landscape has work to do, but it might be helpful to do this work together. Initiatives for collecting circularity data by nonprofits such as EMF and WBCSD have been promising. ESG reporting organizations can benefit from partnering with such circularity experts, to ensure their current questionnaires and standards accurately capture how circularity is helping companies combat climate change.

As for the companies implementing circularity initiatives, data collection about the comprehensive impacts that circularity can have on a business should be at the top of the sustainability manager’s to-do list. But such disclosure cannot exist as a standalone report. If companies are looking to improve their circularity disclosure, the goal should be to leverage existing reporting mechanisms to include data on how robust the company’s circularity strategy is and how closely it integrates with sustainability and business priorities.

As the space of ESG disclosure evolves, circularity should move away from being an aspiration listed on the company’s website to being a core framework for measuring its comprehensive climate progress.

"The circular economy is needed to get to net-zero emissions"

Ellen MacArthur | Leave a comment

Designers and brands must go beyond recycling and focus on making bigger, systems-level changes to help the world move to a circular economy and ultimately reach its net-zero goals, says Ellen MacArthur.

Today, we use the equivalent of 1.6 Earths a year to provide the resources we use and absorb our waste. This means it takes the planet one year and eight months to regenerate what we use in a single year.

Much like running up financial debts, which can result in bankruptcy, when we draw down too much stock from our natural environment without ensuring and encouraging its recovery, we run the risk of local, regional and eventually global ecosystem collapse. The circular economy is a way to solve this by decoupling economic growth from the consumption of finite resources.

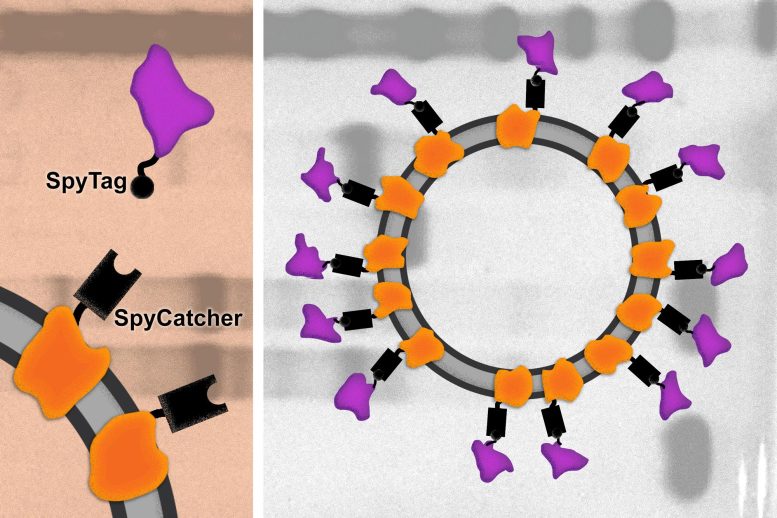

It's about redesigning products, services and the way our businesses work to shift our whole economy from one that is locked into a take-make-waste system to one that eliminates waste, circulates products and materials, and regenerates nature.

Designers must go way beyond simply rethinking how they make individual products

The circular economy gives us a framework that can help to solve our biggest global challenges at the same time. And the last two years have seen circular design and innovation rapidly increasing, pretty much everywhere.

Around the world, we are seeing more and more businesses use the circular economy to change the way they work and tackle the root causes of climate change, biodiversity loss, waste and pollution.

However, to drive action forward, it is crucial that we focus upstream to prevent waste before it is created. Designers must go way beyond simply rethinking how they make individual products and consider the entire system that surrounds them.

This includes the business models, the ways in which customers access products and what happens to those products when we have finished with them, so we can keep the materials in the system for as long as possible.

The opportunities are clear and renewed ambition levels from 2021 are positive but shifting the system is a challenge. We need scale and we need it quickly.

Some very strong examples of designers and big companies innovating for a circular future are featured in the Ellen MacArthur Foundation's recent study, which focused on rethinking business models for a thriving fashion industry.

Innovation continues to ramp up as the world seeks solutions to plastic pollution

Research revealed that by maximising the potential of economic and environmental impacts, circular business models in sectors such as rental, resale, remake and repair have the potential to claim 23 per cent of the global fashion market by 2030 and grasp a $700 billion opportunity.

The study cites tangible examples of how businesses such as [luxury resale platform] The RealReal and Rent the Runway (RTR), among many others, are innovating to embrace circular models.

In other industries, we are seeing refurbished electronics as a growing space. This January, Back Market – a Paris-based business that refurbishes iPhones – was valued at $5.7 billion, making it France's most valuable startup.

Innovation continues to ramp up as the world seeks solutions to plastic pollution. But invariably, this market faces a lot of its own barriers. Efforts concentrating on downstream solutions such as recycling are undoubtedly a necessary component.

But we need to ensure that we eliminate all problematic and unnecessary plastic items, innovate to ensure that the plastics we do need are reusable, recyclable or compostable, and circulate all the plastic items we use to keep them in the economy and out of the environment.

The circular economy is needed to get to net-zero emissions. While 55 per cent of emissions can be tackled by the transition to renewable energy, the remaining 45 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions come from the way we make and use products and food, and manage land.

To deliver the climate and biodiversity benefits of a circular economy, businesses and governments must work together to change the system, and this means redesigning the way we make and use products and food. This shift will give us the power to not only reduce waste, pollution and greenhouse gas emissions but also to grow prosperity, jobs, and resilience.

We are continuing to witness an abundance of positive circular innovation centred at tackling climate change – not least UK-based Winnow, which works to reduce food waste through data and now saves 61,000 tonnes of carbon emissions per year. Our next steps must be to ensure that continuing innovation is supported and enabled to accelerate and scale.

We need to work together to create a system that allows us all to make better choices

Transitioning to the circular economy requires all stakeholders across systems to play their part. The role of all businesses, regardless of size, is vital if we are to find new, circular ways of creating, delivering and capturing value that also benefits society and the environment. No one can say how long this transformation will take, but what we can say is that it is already well underway.

We need businesses and governments to work together to create a system that allows us all to make better choices, choices that are part of the solution to global challenges rather than part of the problem.

Ellen MacArthur is a former round-the-world sailor, who retired from yachting to launch the Ellen MacArthur Foundation in 2010. Dedicated to accelerating the shift towards a circular economy, the charity has partnered with some of the biggest brands in the world and published a number of influential reports on plastic pollution and textile waste, alongside practical guides on how to design products and garments in a more circular way.