South Carolina Targets Free Speech in Its Attempt to Limit Abortion Access

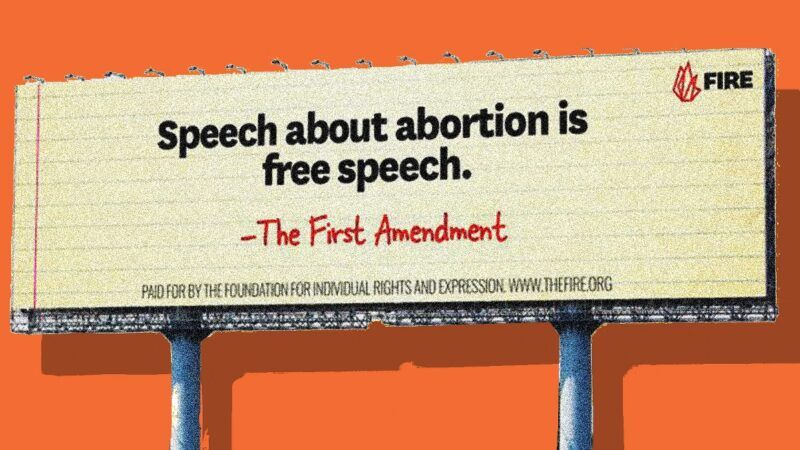

Billboards remind state residents that controversial speech enjoys First Amendment protection.

One challenge prohibitionists face is that not everybody supports their prohibitions. Many people under their nominal authority want access to what's forbidden, no matter what the law says.

Aware that the procedure remains available elsewhere, South Carolina lawmakers seeking a near-complete ban on abortion propose to forbid speech about terminating pregnancies to prevent residents of the Palmetto State from learning of such services. The recently rebooted Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) is reminding `them that speech that politicians don't like is not only the best speech but is also protected by the First Amendment.

"Speech about abortion is free speech–The First Amendment," reads the advertisements placed across South Carolina in "a six-figure billboard campaign" by FIRE, which recently adopted a new name and expanded its scope beyond academia to embrace broad civil liberties advocacy.

The billboards are going up in Charleston, Columbia, Greenville, and Myrtle Beach as South Carolina lawmakers debate not just new restrictions on abortion in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, but also restrictions on informing women about how to terminate pregnancies beyond the law's reach. Ambitious and almost certainly unconstitutional proposed legislation would prohibit "providing information to a pregnant woman, or someone seeking information on behalf of a pregnant woman, by telephone, internet, or any other mode of communication regarding self-administered abortions or the means to obtain an abortion, knowing that the information will be used, or is reasonably likely to be used, for an abortion." Violation of the law would be a felony, punishable by up to 25 years in prison depending on the specific offense.

The proposed censorship of abortion information comes as state legislators consider tighter restrictions in the wake of Dobbs. Language now being debated would ban all abortions, except for those necessary to preserve the life and health of the mother. Even some anti-abortion lawmakers find that too restrictive and are holding out for the inclusion of exceptions for abortions in the case of rape or incest.

Whatever the final form, though, tighter restrictions on abortion are likely to send some women looking for abortion-inducing drugs, or for information on traveling out of state to end pregnancies. Preventing such end runs is the goal of the companion bill banning information "regarding self-administered abortions or the means to obtain an abortion." The language was clearly inspired by model legislation crafted by the National Right to Life Committee as "a robust enforcement mechanism" to ensure that state-level abortion bans are effective. That model has already been dismissed by legal experts as almost certainly unconstitutional.

"In Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), the Supreme Court struck down a state law that prohibited encouraging or prompting an abortion by the sale or circulation of any publication," First Amendment lawyer Robert Corn-Revere noted last month for Reason. "The Court held the First Amendment protects such speech. It observed that, just as Virginia lacked constitutional authority to prevent its residents from traveling to New York to obtain abortions, it could not, 'under the guise of exercising internal police powers, bar a citizen of another State from disseminating information about an activity that is legal in that State.'"

Even as they consider a ban on speech that might help women end their pregnancies, many South Carolina lawmakers seem to understand that the project is a non-starter, destined to perish in the courts after the inevitable challenge.

"[Sen. Richard] Cash's bill has received a lot of attention since he introduced it June 28, shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned nearly 50 years of precedent on abortion rights and left the legality for state lawmakers to decide," reports the Post and Courier, which notes significant opposition even among pro-life lawmakers. "But it's not expected to get any traction.

So, if the censorship bill is not expected to pass, why is FIRE making a fuss? Well, legislators have a history of surprising people by enacting legislation that observers consider ridiculous, but which become law despite all predictions and common sense. Right now, youth shooting teams and publications are awaiting the outcome of lawsuits against the state of California over a broadly written law that bans "marketing" guns to minors but encompasses speech about policy and shooting sports.

"A gun magazine publisher, for instance—or a gun advocacy group that publishes a magazine—would likely be covered as a 'firearm industry member,' because it was formed to advocate for use or ownership of guns, might endorse specific products in product reviews, and might carry advertising for guns," UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh cautioned in testimony before the legislation passed.

Holding the line now is a good policy so that somebody doesn't have to risk a felony conviction in the future in order to wage an after-the-fact legal battle. Complacency is just a bad idea when liberty is at stake.

Plus, the debate over the censorship measure is an opportunity to remind Palmetto State residents that there are alternatives to obeying restrictive laws. Discussions of free speech about abortion can quickly turn into conversations about the content of that speech, pointing women towards out-of-state clinics and resources like Plan C, maintained by the National Women's Health Network, which offers advice for getting mail-order abortion pills. That is, an attempt to muzzle speech becomes a means of amplifying the targeted speech to reach a wider audience.

Fundamentally, though, whatever your opinion of abortion or other controversial issues, frustrating control freaks' efforts to muzzle the sharing of information should be something we can all get behind.

"These proposals are a chilling attempt to stifle free speech in South Carolina," points out FIRE Legal Director Will Creeley. "Whether you agree with abortion or not is irrelevant. You have the right to talk about it."

Interestingly, South Carolina lawmakers' efforts to tighten abortion restrictions may falter based on the state's own constitutional protections. On August 17, the South Carolina Supreme Court temporarily blocked enforcement of a 2021 law limiting abortions that went into effect with the Dobbs decision.

"At this preliminary stage, we are unable to determine with finality the constitutionality of the Act under our state's constitutional prohibition against unreasonable invasions of privacy," the court unanimously ruled.

Abortion may or may not stay legal in South Carolina, but the state's residents are destined to a vigorous and very informative conversation about the issue, and about speech itself.