Enhancing the safety and efficacy of drone flights in polar regions

Scientists devise onboard particle counters that enable real-time detection of icing conditions by drones

IMAGE:

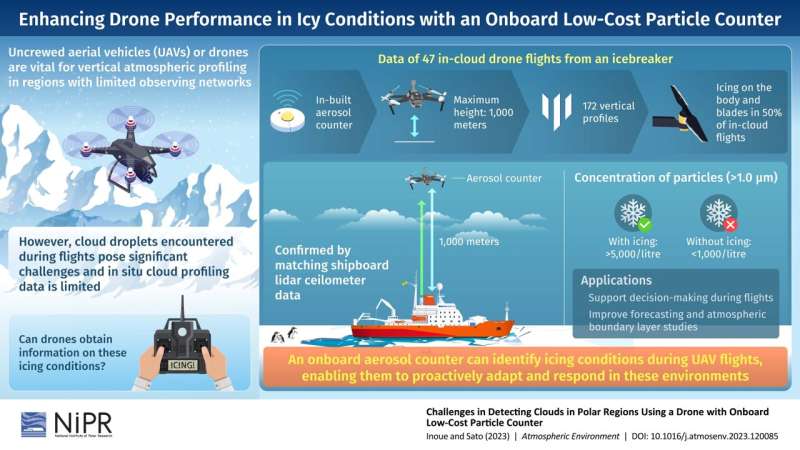

AN ONBOARD AEROSOL COUNTER CAN IDENTIFY ICING CONDITIONS DURING DRONE FLIGHTS, ENABLING THEM TO ADAPT AND RESPOND IN THESE EXTREME ENVIRONMENTS

view moreCREDIT: @ JUN INOUE FROM NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF POLAR RESEARCH, JAPAN

Collecting accurate weather data in remote and challenging environments like the polar regions and mountains can be extremely difficult. These areas often lack the infrastructure and resources needed for traditional weather stations, and the harsh weather conditions can make it dangerous for humans to access and maintain these stations.

Drones can navigate these challenging terrains, gather data, and transmit it to researchers, making them an indispensable tool for addressing these data gaps. Unfortunately, in-cloud flights still pose a challenge, with icing from supercooled cloud droplets that can damage vital drone components, rendering them inoperable.

To solve this problem, Drs. Jun Inoue and Kazutoshi Sato from the National Institute of Polar Research, Japan, came together to devise a creative solution: they integrated onboard aerosol counters into a group of drones used during the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition of 2022/2023. The study was made available online on 16 September 2023 and is set to be published in Volume 314 of Atmospheric Environment on 1 December 2023.The scientists used the aerosol counters, which are typically used to measure the concentration of particles in the air, to detect the presence of clouds during drone flights.

"Under usual conditions in our expedition, we typically observe concentrations of fewer than a thousand particles per liter," explained Dr. Jun Inoue. "However, when we encounter icing conditions, we see concentrations of 5,000 particles per liter or even higher." This change enables the drones to promptly detect and respond to hazardous conditions in real-time.

During meteorological vertical profiling, which involves the information of atmospheric conditions at different altitudes, the drones do not need to travel far horizontally, making it easier to decide when to descend in icing conditions. The aerosol counter plays a pivotal role in this scenario, as it empowers drone operators to make informed decisions promptly.

To further confirm the reliability of this method, the scientists compared the counters’ observations with data collected from a shipboard lidar ceilometer. The ceilometer provides critical information about cloud properties, such as their height and whether they consist of water or ice. The authors examined the attenuated backscatter coefficient, which indicates how light bounces off the clouds, and were able to establish a clear connection between the increased particle counts detected by the aerosol counter based on 47 in-cloud flights and the presence of supercooled liquid clouds.

The counters successfully detect icing conditions among half of the in-cloud flights, which reached heights of approximately 1,000 meters above the sea level. This information helped the drones avoid flying through dangerous icing conditions.

Drones can be a valuable tool for studying the atmosphere, especially in places like the polar regions, and these findings can improve our understanding of clouds and weather. “With continued innovation and collaboration, drones can revolutionize meteorological research, ultimately benefiting our comprehension of clouds, weather, and their broader implications," Dr. Inoue concludes.

###

About National Institute of Polar Research, Japan

Founded in 1973, the National Institute of Polar Research (NIPR) is an inter-university research institute that conducts comprehensive scientific research and observations in the polar regions. NIPR is one of the four institutes constituting the Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS) and engages in comprehensive research via observation stations in the Arctic and Antarctica. It strives to promote polar science by soliciting collaboration research projects publicly, as well as by providing samples, materials, and information. NIPR plays a special role as the only institute in Japan that comprehensively pursues observations and research efforts in both the Antarctic and Arctic regions.

Website: https://www.nipr.ac.jp/english/index.html

About Associate Professor Jun Inoue from National Institute of Polar Research, Japan

Dr. Jun Inoue obtained his master’s and PhD degrees from Hokkaido University, Japan, in 1999 and 2001, respectively. He currently serves as an Associate Professor at the National Institute of Polar Research. His research interests lie in the fields of atmospheric and hydrosphere science, particularly in the Arctic and Antarctic regions. He has published over 100 papers on these topics and has received awards from the Japan Meteorological Society on three occasions.

About the Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS)

ROIS is a parent organization of four national institutes (National Institute of Polar Research, National Institute of Informatics, the Institute of Statistical Mathematics and National Institute of Genetics) and the Joint Support-Center for Data Science Research. It is ROIS's mission to promote integrated, cutting-edge research that goes beyond the barriers of these institutions, in addition to facilitating their research activities, as members of inter-university research institutes.

JOURNAL

Atmospheric Environment

ARTICLE TITLE

Challenges in Detecting Clouds in Polar Regions Using a Drone with Onboard Low-Cost Particle Counter

Enhancing the safety and efficacy of drone flights in polar regions

Collecting accurate weather data in remote and challenging environments like the polar regions and mountains can be extremely difficult. These areas often lack the infrastructure and resources needed for traditional weather stations, and the harsh weather conditions can make it dangerous for humans to access and maintain these stations.

Drones can navigate these challenging terrains, gather data, and transmit it to researchers, making them an indispensable tool for addressing these data gaps. Unfortunately, in-cloud flights still pose a challenge, with icing from supercooled cloud droplets that can damage vital drone components, rendering them inoperable.

To solve this problem, Drs. Jun Inoue and Kazutoshi Sato from the National Institute of Polar Research, Japan, came together to devise a creative solution: they integrated onboard aerosol counters into a group of drones used during the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition of 2022/2023.

The study is published in Atmospheric Environment.The scientists used the aerosol counters, which are typically used to measure the concentration of particles in the air, to detect the presence of clouds during drone flights.

"Under usual conditions in our expedition, we typically observe concentrations of fewer than a thousand particles per liter," explained Dr. Jun Inoue. "However, when we encounter icing conditions, we see concentrations of 5,000 particles per liter or even higher." This change enables the drones to promptly detect and respond to hazardous conditions in real-time.

During meteorological vertical profiling, which involves the information of atmospheric conditions at different altitudes, the drones do not need to travel far horizontally, making it easier to decide when to descend in icing conditions. The aerosol counter plays a pivotal role in this scenario, as it empowers drone operators to make informed decisions promptly.

To further confirm the reliability of this method, the scientists compared the counters' observations with data collected from a shipboard lidar ceilometer. The ceilometer provides critical information about cloud properties, such as their height and whether they consist of water or ice.

The authors examined the attenuated backscatter coefficient, which indicates how light bounces off the clouds, and were able to establish a clear connection between the increased particle counts detected by the aerosol counter based on 47 in-cloud flights and the presence of supercooled liquid clouds.

The counters successfully detect icing conditions among half of the in-cloud flights, which reached heights of approximately 1,000 meters above the sea level. This information helped the drones avoid flying through dangerous icing conditions.

Drones can be a valuable tool for studying the atmosphere, especially in places like the polar regions, and these findings can improve our understanding of clouds and weather. "With continued innovation and collaboration, drones can revolutionize meteorological research, ultimately benefiting our comprehension of clouds, weather, and their broader implications," Dr. Inoue concludes.

More information: Jun Inoue et al, Challenges in Detecting Clouds in Polar Regions Using a Drone with Onboard Low-Cost Particle Counter, Atmospheric Environment (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.120085

Journal information: Atmospheric Environment

Provided by Research Organization of Information and SystemSeveral findings that could enable drones to de-ice their wings automatically