“All is quiet, but it's not a good time to visit”: How anti-Semitic protests changed the lives of Dagestani Jews

LONG READ

Maria Alexeeva

17 November 2023

On November 14, the Russian Interior Ministry put on the wanted list the administrator of the Utro Dagestan Telegram channel, which had been calling for anti-Semitic riots in the republic. On October 29, a mob stormed Makhachkala airport looking for “Israeli refugees.” The authorities of Dagestan declared the riots “planned from the outside” and assured there was no anti-Semitism in the republic. Meanwhile, social media are rife with calls to stop renting apartments to Yahudi (the Arabic for “Jews”), and Dagestanis living in Israel are afraid to visit their relatives back home. Oded Forer, chair of the Knesset’s Immigration, Absorption, and Diaspora Affairs Committee has appealed to the Jewish community of Dagestan to leave for Israel. The Insider's correspondent traveled to Derbent, formerly home to the largest diaspora of Mountain Jews in the North Caucasus, and spoke with locals to find out how they live among the republic's mostly Muslim population and how the conflict in Israel is changing their lives.

CONTENT

“They're fighting for the Zionists!”

“We'd rather make do without flights than see something horrible happen”

“We're reasonable people and normally live in peace”

“Palestine, we stand with you!”

“How can you call for their expulsion? They're ours!”

RU

“They're fighting for the Zionists!”

The house on Sadovaya Street in the highland village of Nyugdi in Derbent District is empty. The neighbors haven't seen its owner, Livi Sadiyaev, 58, or his wife in days. His car service center in the neighboring village of Bilidzhi is also closed. The Sadiyaevs, who are Mountain Jews, left when Dagestanis essentially declared open season on the Jewish population.

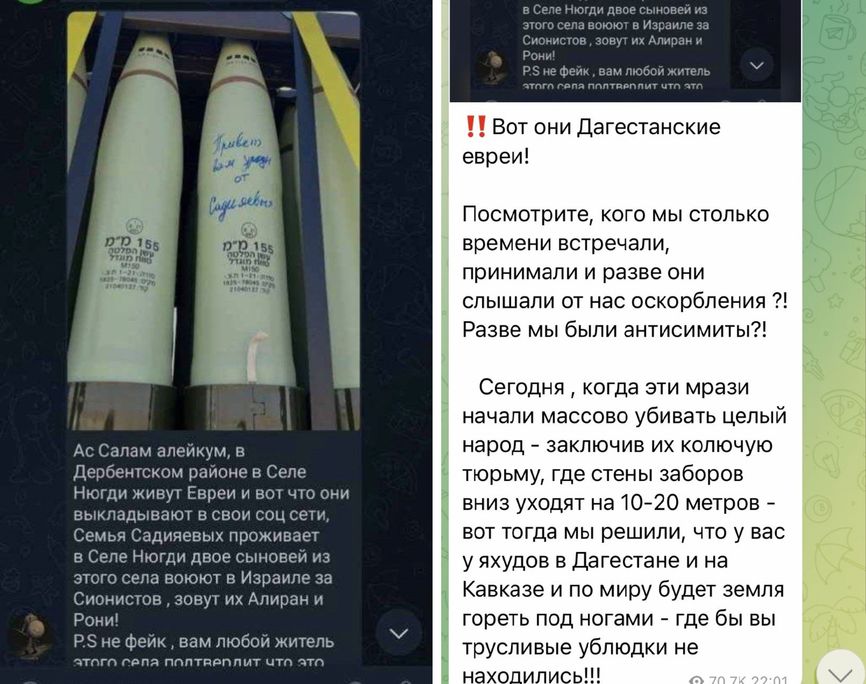

“The Sadiyaev family lives in the village of Nyugdi, and two sons from this village are in Israel, fighting for the Zionists; their names are Aliran and Roni! It's not a hoax!” Such a post appeared in the Utro Dagestan Telegram channel, followed by calls for the persecution of Yahudi or “Zionists.” The channel was soon blocked, but the post went viral on other social networks, ruining the peaceful life of a family that had resided in Nyugdi for decades.

The hatred was triggered by a photo of a rocket taken by one of Livi's sons, who is fighting in the Israel Defense Forces against Hamas. On it, he wrote: “This is for you freaks, from the Sadiyaevs.” According to the neighbors, the father shared the photo with his acquaintances, expressing his approval. Both the image and his comment ended up on social media. Users in the comments began calling to “avenge the Palestinians.” The police secured Livi's house, and a video of Livi apologizing appeared on social media:

“I realize my mistakes and apologize to the Derbent District, Derbent, and all of Dagestan.”

“He who comes to us with a sword will die by the sword,” the village of Nyugdi, Sadovaya Street

The Sadiyaevs were one of the few remaining Jewish families in Nyugdi, historically a settlement of Mountain Jews. A strip of such communities is stretched across the modern southern Dagestan and northern Azerbaijan. Today Nyugdi has a predominantly Muslim population of just over 2,000 people, but in the 19th century, 68 of Nyugdi's 74 households were Jewish. In the 1990s, most of the Jews left Nyugdi for Israel, including Livi Sadiyaev's sons Eliran and Roni. Livi and his wife stayed, but no one can tell if it's safe for them to return to their home.

“Livi's a fool to have done that, of course. Why would he share it? He knows it was an emotional gesture. What's happened makes me very sad,” says Sabina (name changed), a resident of Nyugdi.

We’re standing outside the village council building, which was once a synagogue. Despite the recent renovation in 2009, the building looks as though it was about to fall apart. The village also has a functioning mosque and an Armenian church, but the Armenians are all gone, so the church is just a tourist attraction.

Police stopped patrolling Sadovaya Street after Livi Sadiyaev left

The shop assistants near the former synagogue speak Azerbaijani, as the village is about 20 kilometers from the border with Azerbaijan. Sabina, my interviewee, is Lezgin. According to Livi's neighbors, ethnic diversity was always key to preventing sectarian conflicts in the village.

“This is Livi's homeland,” says Sabina. “He was born here, studied, and performed with a band, singing songs of Mountain Jews. He fought in Afghanistan in the 1980s and then went into business and agriculture. How's he supposed to move now?”

“My heart goes out to him. He let his emotions get the better of him,” says local farmer Islam. “I myself have a son in the Russian army, fighting in the SVO [special military operation] for a year and a half. My heart hurts every day, so Livi’s probably does too. But not everyone is so understanding! The post came about when there was a rally at the airport, when passions were flying high, and our youth mostly supports Palestine. Now it seems things have changed for good.”

Nyugdi

For now, all is quiet in Nyugdi. Locals are harvesting persimmons and pomegranates and hope there will be no more unrest. Still, the air is filled with tension: the neighbors refuse to discuss the recent events, in stark contrast to Dagestanis’ habitual openness and loquacity. The shell photo, the harassment of the family, and the pogrom at the airport came as a shock to many, both in the village and in Derbent, which is now home to the largest community of Mountain Jews in the North Caucasus.

“We'd rather make do without flights than see something horrible happen”

“I don't think any Jews left Derbent after the pogrom at the airport. On the contrary, I believe people started coming back when the fighting in Israel broke out – if only to sit it out. Everyone is welcome,» says Vera, a hotel manager from Derbent. “We’ve got nothing to fight about. We've all lived here for a long time.”

I meet Vera at “Grisha's House,” a local landmark. Now a restaurant and art space, in the 20th century this building was owned by a famous Derbent businessman and philanthropist of Jewish origin. Dates, business meetings, underhanded deals – all sorts of things took place at “Grisha's House”.

Jews began to settle in Derbent in the 19th century, and its central district was soon even dubbed the Jewish Quarter. The area wasn't considered the most prestigious, but it wasn't the worst either. Armenians and Russians lived closer to the sea, says Vera. In 1917, Derbent had 11 synagogues, but the Soviet government later closed all of them, except for the now-active Kele-Numaz.

“Grisha's House” used to be the heart of Derbent

The pogroms at Makhachkala airport scared tourists away from Derbent, but not for long, according to employees of several hotels, including Vera’s. About one-third of her hotel's guests canceled reservations after Oct. 29. However, just a week later, new reservations started to come through.

The pogroms at Makhachkala airport scared tourists away from Derbent, but not for long

The storming of the airport “surprised and perplexed” Vera. Most of our interviewees described their emotions similarly. Vera didn’t realize the scale of what was happening until the barrage of calls from her concerned relatives and friends in Moscow, Baku, and Israel. They were offering her to leave Derbent and come stay with them, but she refused. She fears that moving will only add to her anxiety.

“Where's it easy now? This is my home. Not only Jews have a good reason to worry but also Christians, Muslims, and atheists. All reasonable people. Luckily, people are mostly reasonable around here. I know everyone,” the woman says. She’s lived in Dagestan all her life, but her daughter and son left, like many local Jews, and are now studying in Israel.

In their calls to search for Jews at the airport, the authors of the Utro Dagestan Telegram channel, which coordinated the protests, clarified that they were targeting refugees from Israel and not locals of Jewish origin. But Vera and many other Jewish community members were not reassured by this.

The rally outside the airport terminal in Makhachkala, October 29

Photo by Ramazan Rashidov / TASS / dpa / picture alliance

“They said they were against Zionists, Israelis, and not against us local Jews – but we have children and relatives in Israel!” the woman exclaims. “Maybe it's a good thing that flights from Tel Aviv have been canceled? Because a lot of people come to visit. Children come to check on their parents and vice versa. We have large families, five or six kids each, and then there are also nephews, brothers, and sisters. We'd rather make do without flights than see something horrible happen!”

The riot at the airport was not the first, but rather the last in the series of anti-Semitic protests in the North Caucasus. On the same day, a spontaneous rally in support of Palestine and against Israel was held in Makhachkala. In Nalchik, unknown individuals set fire to a Jewish center under construction and wrote “Death to Yahudi” on the building. On Saturday, October 28, a few dozen residents of Khasavyurt came to the Flamingo Hotel and demanded proof there were no Jews in the hotel, tossing stones at the building. A rally demanding to keep out “Jewish refugees” was also held in Cherkessk.

Derbent managed to avoid riots. All our interviewees are sure their city is too tolerant and peaceful for any kind of pogroms.

Derbent's “Jewish Quarter”

They interpret what happened as a one-time outburst of hatred triggered by some external influence, but no one knows what caused it in the first place. The topic makes everyone uneasy.

“We're reasonable people and normally live in peace”

“No, no, no! Neither I nor the head of the community will tell you anything about it today! Makhachkala told us to keep our heads down and our mouths shut,” said a representative of Derbent's Jewish community when asked how the storming of the airport had affected the lives of local Jews. He said the order “to avoid speculation” came from Moscow, where the community's chair and chief rabbi headed shortly after the riots. A couple of minutes later, Ilya (name changed) agreed to talk on condition of anonymity.

We meet him at the old Jewish cemetery in Derbent. The cemetery is more than 240 years old, Ilya says, and almost every local Jew has relatives buried here. “My mother is buried in Israel, but my father is buried here, and so is my grandmother, who raised me,” Ilya shares. “And I'm not leaving.”

A cemetery visitor and a worker lay tiles at a Jewish cemetery in Derbent

However, Ilya urges his relatives not to visit Dagestan for the time being. He has six children, five of whom are in Israel. They visit their father regularly – or rather, they did before the airport pogrom. The last ones to arrive in September were his daughter and grandson, who left a day before the pogrom.

“I told them all: sit tight, don't even think of coming! Let's wait till things get back to normal.”

Ilya urges his relatives not to visit Dagestan for the time being

Ilya doesn’t believe any Israelis will go to Russia to sit out the shelling, even if the war in the Gaza Strip drags on.

“Trust me, no Jew will ever come to Dagestan or Russia for love or money! I sometimes talk to my children and brothers and invite them to stay, but they always say Moscow will never be as good as Israel. We’re indeed preserving an entire state today. Even with the war going on, we'll keep it. All the more so considering the war’s not all over Israel.”

Israel's ambassador to Russia has urged Israelis not to visit the North Caucasus until Russian authorities declare it safe to do so. So far, there have been no such assurances, though the leadership of Dagestan is trying its best to show the absence of the problem. Ilya also insists there’s no threat to Jews in Dagestan, that “the head of the republic and Vladimir Putin have everything under control and everything will be nice and quiet, without any chaos.”

Stickers in support of Palestine in Derbent

“Local Jews sometimes marry non-Jews: Dargins, Avars, Lezgins. One of my sons, who lives in Moscow, has an Avar wife. I remember him coming to me and saying: ‘Dad, I really like her!’ What was I to do?” explains my interviewee. “Maybe that's why we reasonable people normally live in peace. We need to show humanity in some matters, not dogmatism.”

At the same time, about 70% of Derbent's Jews are religious, Ilya claims. As he recalls, once upon a time dozens of young men and girls in Derbent gathered to study Torah. Today young people are less “preoccupied” with religious issues. «To be religious, you have to read it all, study it all! Ilya shows a book wrapped in a black cover that he brought with him. This is the Torah: Mountain Jews wrap holy books in a double cloth cover. Unlike in other Jewish communities, it’s against their tradition to touch the books with bare hands.

Cemetery workers who are installing a tombstone on a nearby grave overhear our conversation with Ilya. One of them chips in to answer my question about the spread of radical Islam among Dagestani youth:

“They listen to some preachers online and then teach us how to pray. They teach old people to pray, can you imagine that? They think they are better Muslims than we are! Our society has always been very tolerant, in a good sense. But they're hardliners. They don't listen to us. As they say, it's not our tradition. We've never had anything like this before.”

“Caliphate” and “Islamic Caliphate” graffiti appear on buildings, fences, and transformers in and outside Makhachkala

His buddy also mentions religious arguments with the younger generation:

“My neighbor's grandson says to me: ‘You should pray more as you absolve yourself of your sins with every prayer!’ And I say: ‘So why do you sin so much that you have to pray all the time?’”

Ilya and the cemetery workers explain the events at the airport as a “foreign invasion,” agreeing with the head of the republic, Sergey Melikov. My interviewees believe the authorities should reach out to radical youth to avoid repeating the situation.

“Do they engage with young people? Are there any initiatives?”

“Well... the other day Vladimir Putin held a meeting with representatives of all confessions,” Ilya says after a pause. As if correcting himself, he continues: “In fact, Russia’s never had a president like him, believe me. Even under the Romanovs, there was no such order and such authority in Russia as there is now!”

Both the community leadership and the Dagestani government delicately deny the existence of any inter-confessional enmity, either in the past or at present. Officially, there’s no anti-Semitism in Derbent, and the events at the airport were an isolated incident. But the synagogue in Derbent closed its doors for 10 days for security reasons “because a lot of people come there to pray,” my interviewee explained.

Officially, there’s no anti-Semitism in Derbent, and the events at the airport were an isolated incident

Kele-Numaz Synagogue in Derbent

We say goodbye to Ilya late at night. Lastly, I ask him if he felt personally threatened after the events at the airport. He is evasive. “Thank God, we were lucky here in Derbent, and the riots didn't spill over. Dargins, Lezgins live with us; we are one. We hang out and drink tea; we visit each other. For me, they’re neighbors first of all, and whether they are Avar or Lezgin Muslim doesn't matter to me. We have 36 nationalities here, and we’re all like brothers.”

However, local taxi drivers have trouble fitting into the picture of universal friendship that Ilya, Vera, and other Derbent interviewees so diligently painted for me: “I'm sick of the Jews! They sully Russia. They sully the entire world. Local, non-local, whatever. They're getting cocky. We saved them in the Great Patriotic War, 20 million died, and now they’ve turned against Russia. They’re helping the Banderites!” rants Abdulnasir, a 60-year-old taxi driver. He doesn’t seem to remember that Jews died on WWII battlefields alongside representatives of other nationalities, even though the Jewish cemetery in Derbent has a huge monument in memory of the Jews killed during the war.

A WWII memorial in Derbent to honor the fallen Jews

In another taxi, from Derbent to Makhachkala, driver Ali argues with the other passenger about anti-Jewish sanctions: “I’ve deleted Yandex Taxi altogether, because all of the team is Jewish, and they support this war,” Ali explains. He’s 20 or so, a Kaspiysk native, and a supporter of Palestine. He recalls that he was at the airport on the day of the pogrom, to “support the brothers.” But he wouldn't go into the terminal building. “I pick up passengers there. I know there are cameras everywhere, and I don't want any trouble.”

The closer you get to Makhachkala, the more cars have stickers in support of Palestine

Police cars are whizzing by with sirens blaring. Law enforcers were deployed in Makhachkala and on the roads leading to the Dagestani capital because the day before, Telegram channels started posting calls for a pro-Palestinian and anti-Israeli rally in the city center. “Traffic cops are everywhere now, even in places where we haven't seen any in a while. Policemen are patrolling the entrances and exits of villages in Khasavyurt and Kizilyurt districts, and there are even more in the towns,” warns a Dagestani pro-Palestinian Telegram channel.

“Palestine, we stand with you!”

We drive to Makhachkala via Kaspiysk, where “a lot of young people sympathize with the Palestinians,” Ali tells me. It was from Kaspiysk and Buynaksk, he said, that most of the participants in the October 29 airport rally arrived. Occasionally, we are overtaken by cars with “Palestine, we stand with you!” stickers. At a traffic circle near the airport, someone stretched a huge Palestinian flag.

On the morning of the rally, anti-Israeli stickers and posters appeared in Makhachkala, calling to boycott Israeli products, not to rent apartments or houses to “Jewish refugees,” and to refuse them service in restaurants and taxis. “All of you are witnesses to how Palestine has sheltered them and the gratitude it has received,” said a publication on a now-blocked Telegram channel. “Today Palestinian children are dying at their hands, and tomorrow it could affect our people.”

One of the pro-Palestinian stickers appeared outside a synagogue despite the building being guarded 24 hours a day by the police. Like in Derbent, the synagogue in Makhachkala has also been closed.

On the evening of November 5, police from all over Dagestan were summoned to Magomed Yaragsky Street, the projected location of the rally: 20 cars per 300 meters, and that's not taking into account the cars and police vans parked in the alleys.

Police officers near Magomed Yaragsky Street

Since Telegram channels had been summoning locals to the protest for several days, the law enforcers had spared no effort in preparing. But other than police officers, no one came, unlike the airport, which was flooded with protesters in less than a couple hours.

Police officers stop and inspect cars on Magomed Yaragsky Street on November 5

“Attended by thousands of law enforcers, the rally for Palestine and in support of the detainees at Makhachkala airport turned out to be a success,” joked social media users on the next day.

“How can you call for their expulsion? They're ours!”

The taxi driver Ali, his passenger, and the elderly driver from Derbent were the only Dagestanis I met who spoke out harshly against both the Israelis and the local Jews. All other Muslims, both young and old, called the actions of the rioters stupid.

“They ruined their own airport. To what end? How does this help the Palestinians?” wonders shawarma chef Aziz. His shop window features a sticker in support of Palestine. But he’s sure Dagestani Jews can't be held responsible for Israel's operation. “They’ve lived here for many years. Their ancestors lived here. This is their homeland too, not Israel, so how can you call for their expulsion? They’re ours! No one’s ever oppressed them here,» Aziz says, and I lose count of the number of times someone said there's no anti-Semitism in Dagestan.

A poster in support of Palestine in a courtyard on Gamidov Avenue, Makhachkala

In reality, there have been episodes in the history of the North Caucasus when intolerance towards local Jews drove them from their homes.

There have been episodes in the history of the North Caucasus when intolerance towards local Jews drove them from their homes

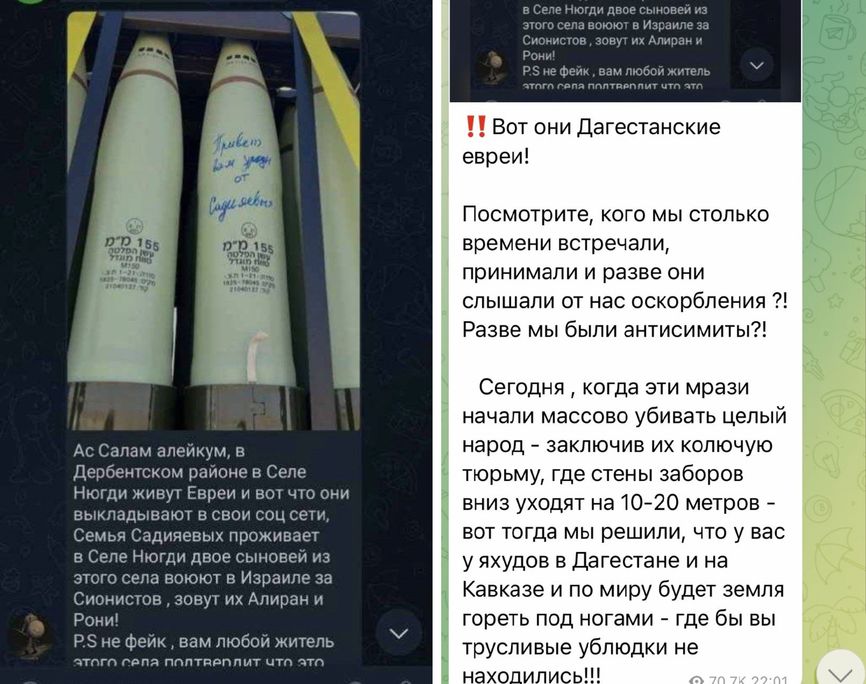

Thus, Jewish communities in Grozny, Nalchik, Kizlyar, and other Russian strongholds emerged after Mountain Jews had to leave some villages, where a surge of intolerance towards non-Muslims during the Caucasian War triggered pogroms and reprisals. On the whole, the Jews of the imperial North Caucasus fared much better than their counterparts throughout Russia. Derbent was the only city in the empire where the authorities disregarded the decree on the Pale of Settlement.

The first Russian-Jewish school in Derbent (1904)

Outbursts of anti-Semitism occurred under Soviet rule as well. In 1926, there was a Jewish pogrom in Makhachkala, initiated by rumors that Mountain Jews had allegedly killed a Muslim child for ritual purposes. The pogroms spread to several settlements, including even tolerant, ethnically diverse Derbent. A similar story happened in the 1960s when a “blood libel” almost led to riots in Buynaksk. Pogroms were then avoided.

In the 1990s, many Jews left the Caucasus and moved to Israel. Their motivation wasn’t purely economic: during the Chechen wars, there were cases of kidnapping for ransom throughout the North Caucasus, including in Makhachkala and Buynaksk. “It's the least risky to kidnap a Jew as there’s no tukhum (clan) behind them. Jews are afraid to complain to anyone and will give up their homes and all their property acquired over several generations without a word, just to preserve the life of a loved one,” the Naslediye portal quoted a Dagestani official as saying in 2001.

In recent years, there have been almost no anti-Jewish protests in Dagestan, except for rare cases of domestic anti-Semitism. But in 2013, Rabbi Ovadya Isakov of the Derbent synagogue survived an assassination attempt. An unidentified man shot him five times at night, and the rabbi was hospitalized in serious condition. Russia's Investigative Committee concluded that the attack could have been linked to Isakov's religious activities. Russia's Chief Rabbi Berl Lazar blamed the jihadist underground for the attack.

Be that as it may, Isakov didn’t leave Dagestan and still holds his position. After the events at Makhachkala airport, he said the situation in the region was complicated and that people were scared. Moreover, he doesn’t feel safe and doesn’t rule out the need to evacuate Jews from Dagestan if this kind of unrest continues. All my interviewees, however, believe this will not be the case and hope they’ll be able to stay in their home region.

On November 14, the Russian Interior Ministry put on the wanted list the administrator of the Utro Dagestan Telegram channel, which had been calling for anti-Semitic riots in the republic. On October 29, a mob stormed Makhachkala airport looking for “Israeli refugees.” The authorities of Dagestan declared the riots “planned from the outside” and assured there was no anti-Semitism in the republic. Meanwhile, social media are rife with calls to stop renting apartments to Yahudi (the Arabic for “Jews”), and Dagestanis living in Israel are afraid to visit their relatives back home. Oded Forer, chair of the Knesset’s Immigration, Absorption, and Diaspora Affairs Committee has appealed to the Jewish community of Dagestan to leave for Israel. The Insider's correspondent traveled to Derbent, formerly home to the largest diaspora of Mountain Jews in the North Caucasus, and spoke with locals to find out how they live among the republic's mostly Muslim population and how the conflict in Israel is changing their lives.

CONTENT

“They're fighting for the Zionists!”

“We'd rather make do without flights than see something horrible happen”

“We're reasonable people and normally live in peace”

“Palestine, we stand with you!”

“How can you call for their expulsion? They're ours!”

RU

“They're fighting for the Zionists!”

The house on Sadovaya Street in the highland village of Nyugdi in Derbent District is empty. The neighbors haven't seen its owner, Livi Sadiyaev, 58, or his wife in days. His car service center in the neighboring village of Bilidzhi is also closed. The Sadiyaevs, who are Mountain Jews, left when Dagestanis essentially declared open season on the Jewish population.

“The Sadiyaev family lives in the village of Nyugdi, and two sons from this village are in Israel, fighting for the Zionists; their names are Aliran and Roni! It's not a hoax!” Such a post appeared in the Utro Dagestan Telegram channel, followed by calls for the persecution of Yahudi or “Zionists.” The channel was soon blocked, but the post went viral on other social networks, ruining the peaceful life of a family that had resided in Nyugdi for decades.

The hatred was triggered by a photo of a rocket taken by one of Livi's sons, who is fighting in the Israel Defense Forces against Hamas. On it, he wrote: “This is for you freaks, from the Sadiyaevs.” According to the neighbors, the father shared the photo with his acquaintances, expressing his approval. Both the image and his comment ended up on social media. Users in the comments began calling to “avenge the Palestinians.” The police secured Livi's house, and a video of Livi apologizing appeared on social media:

“I realize my mistakes and apologize to the Derbent District, Derbent, and all of Dagestan.”

“He who comes to us with a sword will die by the sword,” the village of Nyugdi, Sadovaya Street

The Sadiyaevs were one of the few remaining Jewish families in Nyugdi, historically a settlement of Mountain Jews. A strip of such communities is stretched across the modern southern Dagestan and northern Azerbaijan. Today Nyugdi has a predominantly Muslim population of just over 2,000 people, but in the 19th century, 68 of Nyugdi's 74 households were Jewish. In the 1990s, most of the Jews left Nyugdi for Israel, including Livi Sadiyaev's sons Eliran and Roni. Livi and his wife stayed, but no one can tell if it's safe for them to return to their home.

“Livi's a fool to have done that, of course. Why would he share it? He knows it was an emotional gesture. What's happened makes me very sad,” says Sabina (name changed), a resident of Nyugdi.

We’re standing outside the village council building, which was once a synagogue. Despite the recent renovation in 2009, the building looks as though it was about to fall apart. The village also has a functioning mosque and an Armenian church, but the Armenians are all gone, so the church is just a tourist attraction.

Police stopped patrolling Sadovaya Street after Livi Sadiyaev left

The shop assistants near the former synagogue speak Azerbaijani, as the village is about 20 kilometers from the border with Azerbaijan. Sabina, my interviewee, is Lezgin. According to Livi's neighbors, ethnic diversity was always key to preventing sectarian conflicts in the village.

“This is Livi's homeland,” says Sabina. “He was born here, studied, and performed with a band, singing songs of Mountain Jews. He fought in Afghanistan in the 1980s and then went into business and agriculture. How's he supposed to move now?”

“My heart goes out to him. He let his emotions get the better of him,” says local farmer Islam. “I myself have a son in the Russian army, fighting in the SVO [special military operation] for a year and a half. My heart hurts every day, so Livi’s probably does too. But not everyone is so understanding! The post came about when there was a rally at the airport, when passions were flying high, and our youth mostly supports Palestine. Now it seems things have changed for good.”

Nyugdi

For now, all is quiet in Nyugdi. Locals are harvesting persimmons and pomegranates and hope there will be no more unrest. Still, the air is filled with tension: the neighbors refuse to discuss the recent events, in stark contrast to Dagestanis’ habitual openness and loquacity. The shell photo, the harassment of the family, and the pogrom at the airport came as a shock to many, both in the village and in Derbent, which is now home to the largest community of Mountain Jews in the North Caucasus.

“We'd rather make do without flights than see something horrible happen”

“I don't think any Jews left Derbent after the pogrom at the airport. On the contrary, I believe people started coming back when the fighting in Israel broke out – if only to sit it out. Everyone is welcome,» says Vera, a hotel manager from Derbent. “We’ve got nothing to fight about. We've all lived here for a long time.”

I meet Vera at “Grisha's House,” a local landmark. Now a restaurant and art space, in the 20th century this building was owned by a famous Derbent businessman and philanthropist of Jewish origin. Dates, business meetings, underhanded deals – all sorts of things took place at “Grisha's House”.

Jews began to settle in Derbent in the 19th century, and its central district was soon even dubbed the Jewish Quarter. The area wasn't considered the most prestigious, but it wasn't the worst either. Armenians and Russians lived closer to the sea, says Vera. In 1917, Derbent had 11 synagogues, but the Soviet government later closed all of them, except for the now-active Kele-Numaz.

“Grisha's House” used to be the heart of Derbent

The pogroms at Makhachkala airport scared tourists away from Derbent, but not for long, according to employees of several hotels, including Vera’s. About one-third of her hotel's guests canceled reservations after Oct. 29. However, just a week later, new reservations started to come through.

The pogroms at Makhachkala airport scared tourists away from Derbent, but not for long

The storming of the airport “surprised and perplexed” Vera. Most of our interviewees described their emotions similarly. Vera didn’t realize the scale of what was happening until the barrage of calls from her concerned relatives and friends in Moscow, Baku, and Israel. They were offering her to leave Derbent and come stay with them, but she refused. She fears that moving will only add to her anxiety.

“Where's it easy now? This is my home. Not only Jews have a good reason to worry but also Christians, Muslims, and atheists. All reasonable people. Luckily, people are mostly reasonable around here. I know everyone,” the woman says. She’s lived in Dagestan all her life, but her daughter and son left, like many local Jews, and are now studying in Israel.

In their calls to search for Jews at the airport, the authors of the Utro Dagestan Telegram channel, which coordinated the protests, clarified that they were targeting refugees from Israel and not locals of Jewish origin. But Vera and many other Jewish community members were not reassured by this.

The rally outside the airport terminal in Makhachkala, October 29

Photo by Ramazan Rashidov / TASS / dpa / picture alliance

“They said they were against Zionists, Israelis, and not against us local Jews – but we have children and relatives in Israel!” the woman exclaims. “Maybe it's a good thing that flights from Tel Aviv have been canceled? Because a lot of people come to visit. Children come to check on their parents and vice versa. We have large families, five or six kids each, and then there are also nephews, brothers, and sisters. We'd rather make do without flights than see something horrible happen!”

The riot at the airport was not the first, but rather the last in the series of anti-Semitic protests in the North Caucasus. On the same day, a spontaneous rally in support of Palestine and against Israel was held in Makhachkala. In Nalchik, unknown individuals set fire to a Jewish center under construction and wrote “Death to Yahudi” on the building. On Saturday, October 28, a few dozen residents of Khasavyurt came to the Flamingo Hotel and demanded proof there were no Jews in the hotel, tossing stones at the building. A rally demanding to keep out “Jewish refugees” was also held in Cherkessk.

Derbent managed to avoid riots. All our interviewees are sure their city is too tolerant and peaceful for any kind of pogroms.

Derbent's “Jewish Quarter”

They interpret what happened as a one-time outburst of hatred triggered by some external influence, but no one knows what caused it in the first place. The topic makes everyone uneasy.

“We're reasonable people and normally live in peace”

“No, no, no! Neither I nor the head of the community will tell you anything about it today! Makhachkala told us to keep our heads down and our mouths shut,” said a representative of Derbent's Jewish community when asked how the storming of the airport had affected the lives of local Jews. He said the order “to avoid speculation” came from Moscow, where the community's chair and chief rabbi headed shortly after the riots. A couple of minutes later, Ilya (name changed) agreed to talk on condition of anonymity.

We meet him at the old Jewish cemetery in Derbent. The cemetery is more than 240 years old, Ilya says, and almost every local Jew has relatives buried here. “My mother is buried in Israel, but my father is buried here, and so is my grandmother, who raised me,” Ilya shares. “And I'm not leaving.”

A cemetery visitor and a worker lay tiles at a Jewish cemetery in Derbent

However, Ilya urges his relatives not to visit Dagestan for the time being. He has six children, five of whom are in Israel. They visit their father regularly – or rather, they did before the airport pogrom. The last ones to arrive in September were his daughter and grandson, who left a day before the pogrom.

“I told them all: sit tight, don't even think of coming! Let's wait till things get back to normal.”

Ilya urges his relatives not to visit Dagestan for the time being

Ilya doesn’t believe any Israelis will go to Russia to sit out the shelling, even if the war in the Gaza Strip drags on.

“Trust me, no Jew will ever come to Dagestan or Russia for love or money! I sometimes talk to my children and brothers and invite them to stay, but they always say Moscow will never be as good as Israel. We’re indeed preserving an entire state today. Even with the war going on, we'll keep it. All the more so considering the war’s not all over Israel.”

Israel's ambassador to Russia has urged Israelis not to visit the North Caucasus until Russian authorities declare it safe to do so. So far, there have been no such assurances, though the leadership of Dagestan is trying its best to show the absence of the problem. Ilya also insists there’s no threat to Jews in Dagestan, that “the head of the republic and Vladimir Putin have everything under control and everything will be nice and quiet, without any chaos.”

Stickers in support of Palestine in Derbent

“Local Jews sometimes marry non-Jews: Dargins, Avars, Lezgins. One of my sons, who lives in Moscow, has an Avar wife. I remember him coming to me and saying: ‘Dad, I really like her!’ What was I to do?” explains my interviewee. “Maybe that's why we reasonable people normally live in peace. We need to show humanity in some matters, not dogmatism.”

At the same time, about 70% of Derbent's Jews are religious, Ilya claims. As he recalls, once upon a time dozens of young men and girls in Derbent gathered to study Torah. Today young people are less “preoccupied” with religious issues. «To be religious, you have to read it all, study it all! Ilya shows a book wrapped in a black cover that he brought with him. This is the Torah: Mountain Jews wrap holy books in a double cloth cover. Unlike in other Jewish communities, it’s against their tradition to touch the books with bare hands.

Cemetery workers who are installing a tombstone on a nearby grave overhear our conversation with Ilya. One of them chips in to answer my question about the spread of radical Islam among Dagestani youth:

“They listen to some preachers online and then teach us how to pray. They teach old people to pray, can you imagine that? They think they are better Muslims than we are! Our society has always been very tolerant, in a good sense. But they're hardliners. They don't listen to us. As they say, it's not our tradition. We've never had anything like this before.”

“Caliphate” and “Islamic Caliphate” graffiti appear on buildings, fences, and transformers in and outside Makhachkala

His buddy also mentions religious arguments with the younger generation:

“My neighbor's grandson says to me: ‘You should pray more as you absolve yourself of your sins with every prayer!’ And I say: ‘So why do you sin so much that you have to pray all the time?’”

Ilya and the cemetery workers explain the events at the airport as a “foreign invasion,” agreeing with the head of the republic, Sergey Melikov. My interviewees believe the authorities should reach out to radical youth to avoid repeating the situation.

“Do they engage with young people? Are there any initiatives?”

“Well... the other day Vladimir Putin held a meeting with representatives of all confessions,” Ilya says after a pause. As if correcting himself, he continues: “In fact, Russia’s never had a president like him, believe me. Even under the Romanovs, there was no such order and such authority in Russia as there is now!”

Both the community leadership and the Dagestani government delicately deny the existence of any inter-confessional enmity, either in the past or at present. Officially, there’s no anti-Semitism in Derbent, and the events at the airport were an isolated incident. But the synagogue in Derbent closed its doors for 10 days for security reasons “because a lot of people come there to pray,” my interviewee explained.

Officially, there’s no anti-Semitism in Derbent, and the events at the airport were an isolated incident

Kele-Numaz Synagogue in Derbent

We say goodbye to Ilya late at night. Lastly, I ask him if he felt personally threatened after the events at the airport. He is evasive. “Thank God, we were lucky here in Derbent, and the riots didn't spill over. Dargins, Lezgins live with us; we are one. We hang out and drink tea; we visit each other. For me, they’re neighbors first of all, and whether they are Avar or Lezgin Muslim doesn't matter to me. We have 36 nationalities here, and we’re all like brothers.”

However, local taxi drivers have trouble fitting into the picture of universal friendship that Ilya, Vera, and other Derbent interviewees so diligently painted for me: “I'm sick of the Jews! They sully Russia. They sully the entire world. Local, non-local, whatever. They're getting cocky. We saved them in the Great Patriotic War, 20 million died, and now they’ve turned against Russia. They’re helping the Banderites!” rants Abdulnasir, a 60-year-old taxi driver. He doesn’t seem to remember that Jews died on WWII battlefields alongside representatives of other nationalities, even though the Jewish cemetery in Derbent has a huge monument in memory of the Jews killed during the war.

A WWII memorial in Derbent to honor the fallen Jews

In another taxi, from Derbent to Makhachkala, driver Ali argues with the other passenger about anti-Jewish sanctions: “I’ve deleted Yandex Taxi altogether, because all of the team is Jewish, and they support this war,” Ali explains. He’s 20 or so, a Kaspiysk native, and a supporter of Palestine. He recalls that he was at the airport on the day of the pogrom, to “support the brothers.” But he wouldn't go into the terminal building. “I pick up passengers there. I know there are cameras everywhere, and I don't want any trouble.”

The closer you get to Makhachkala, the more cars have stickers in support of Palestine

Police cars are whizzing by with sirens blaring. Law enforcers were deployed in Makhachkala and on the roads leading to the Dagestani capital because the day before, Telegram channels started posting calls for a pro-Palestinian and anti-Israeli rally in the city center. “Traffic cops are everywhere now, even in places where we haven't seen any in a while. Policemen are patrolling the entrances and exits of villages in Khasavyurt and Kizilyurt districts, and there are even more in the towns,” warns a Dagestani pro-Palestinian Telegram channel.

“Palestine, we stand with you!”

We drive to Makhachkala via Kaspiysk, where “a lot of young people sympathize with the Palestinians,” Ali tells me. It was from Kaspiysk and Buynaksk, he said, that most of the participants in the October 29 airport rally arrived. Occasionally, we are overtaken by cars with “Palestine, we stand with you!” stickers. At a traffic circle near the airport, someone stretched a huge Palestinian flag.

On the morning of the rally, anti-Israeli stickers and posters appeared in Makhachkala, calling to boycott Israeli products, not to rent apartments or houses to “Jewish refugees,” and to refuse them service in restaurants and taxis. “All of you are witnesses to how Palestine has sheltered them and the gratitude it has received,” said a publication on a now-blocked Telegram channel. “Today Palestinian children are dying at their hands, and tomorrow it could affect our people.”

One of the pro-Palestinian stickers appeared outside a synagogue despite the building being guarded 24 hours a day by the police. Like in Derbent, the synagogue in Makhachkala has also been closed.

On the evening of November 5, police from all over Dagestan were summoned to Magomed Yaragsky Street, the projected location of the rally: 20 cars per 300 meters, and that's not taking into account the cars and police vans parked in the alleys.

Police officers near Magomed Yaragsky Street

Since Telegram channels had been summoning locals to the protest for several days, the law enforcers had spared no effort in preparing. But other than police officers, no one came, unlike the airport, which was flooded with protesters in less than a couple hours.

Police officers stop and inspect cars on Magomed Yaragsky Street on November 5

“Attended by thousands of law enforcers, the rally for Palestine and in support of the detainees at Makhachkala airport turned out to be a success,” joked social media users on the next day.

“How can you call for their expulsion? They're ours!”

The taxi driver Ali, his passenger, and the elderly driver from Derbent were the only Dagestanis I met who spoke out harshly against both the Israelis and the local Jews. All other Muslims, both young and old, called the actions of the rioters stupid.

“They ruined their own airport. To what end? How does this help the Palestinians?” wonders shawarma chef Aziz. His shop window features a sticker in support of Palestine. But he’s sure Dagestani Jews can't be held responsible for Israel's operation. “They’ve lived here for many years. Their ancestors lived here. This is their homeland too, not Israel, so how can you call for their expulsion? They’re ours! No one’s ever oppressed them here,» Aziz says, and I lose count of the number of times someone said there's no anti-Semitism in Dagestan.

A poster in support of Palestine in a courtyard on Gamidov Avenue, Makhachkala

In reality, there have been episodes in the history of the North Caucasus when intolerance towards local Jews drove them from their homes.

There have been episodes in the history of the North Caucasus when intolerance towards local Jews drove them from their homes

Thus, Jewish communities in Grozny, Nalchik, Kizlyar, and other Russian strongholds emerged after Mountain Jews had to leave some villages, where a surge of intolerance towards non-Muslims during the Caucasian War triggered pogroms and reprisals. On the whole, the Jews of the imperial North Caucasus fared much better than their counterparts throughout Russia. Derbent was the only city in the empire where the authorities disregarded the decree on the Pale of Settlement.

The first Russian-Jewish school in Derbent (1904)

Outbursts of anti-Semitism occurred under Soviet rule as well. In 1926, there was a Jewish pogrom in Makhachkala, initiated by rumors that Mountain Jews had allegedly killed a Muslim child for ritual purposes. The pogroms spread to several settlements, including even tolerant, ethnically diverse Derbent. A similar story happened in the 1960s when a “blood libel” almost led to riots in Buynaksk. Pogroms were then avoided.

In the 1990s, many Jews left the Caucasus and moved to Israel. Their motivation wasn’t purely economic: during the Chechen wars, there were cases of kidnapping for ransom throughout the North Caucasus, including in Makhachkala and Buynaksk. “It's the least risky to kidnap a Jew as there’s no tukhum (clan) behind them. Jews are afraid to complain to anyone and will give up their homes and all their property acquired over several generations without a word, just to preserve the life of a loved one,” the Naslediye portal quoted a Dagestani official as saying in 2001.

In recent years, there have been almost no anti-Jewish protests in Dagestan, except for rare cases of domestic anti-Semitism. But in 2013, Rabbi Ovadya Isakov of the Derbent synagogue survived an assassination attempt. An unidentified man shot him five times at night, and the rabbi was hospitalized in serious condition. Russia's Investigative Committee concluded that the attack could have been linked to Isakov's religious activities. Russia's Chief Rabbi Berl Lazar blamed the jihadist underground for the attack.

Be that as it may, Isakov didn’t leave Dagestan and still holds his position. After the events at Makhachkala airport, he said the situation in the region was complicated and that people were scared. Moreover, he doesn’t feel safe and doesn’t rule out the need to evacuate Jews from Dagestan if this kind of unrest continues. All my interviewees, however, believe this will not be the case and hope they’ll be able to stay in their home region.

A launch event for the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) in May 2022 ahead of the Quad summit in Tokyo (Adam Schultz/Official White House Photo)

A launch event for the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) in May 2022 ahead of the Quad summit in Tokyo (Adam Schultz/Official White House Photo)