JOVANA GEC and DUSAN STOJANOVIC

Tue, December 12, 2023

Predrag Vostinic, 48, says he became a democracy activist by necessity — his way of pushing back against the rising authoritarianism, government corruption and organized crime gripping the Balkan nation. Since May, a grassroots movement he founded in the central city of Kraljevo has joined weekly protests against the government of President Aleksandar Vucic, part of a wider movement.

He and other members of the group faced threats in the streets and on social media. Other government opponents, in Kraljevo and elsewhere, have been sidelined at work or sacked from their jobs in state-run companies, he said.

Still, he said, it’s worth it: “You become sort of a public voice for people.”

Pro-Western Serbs like Vostinic hoped the EU would act as a counterweight, drawing Serbia back to a more democratic path. Instead, Brussels has held back, as Serbia diverted from the EU's stated values, activists say.

“This is one of the reasons why EU’s losing credibility and why the pro-European part of the Serbian society is in a defensive position, because there is nothing to defend," said Vladimir Medjak, deputy head of the European Movement in Serbia and a former member of the EU membership negotiation team.

Even before Vucic came to power in 2012, Serbia was slow to complete the reforms needed to qualify as an EU candidate, such as ensuring the rule of law and a market economy that could integrate with the bloc. And in recent years, after declaring EU membership a strategic goal, it has instead sought stronger ties with Russia and China.

STRUGGLE FOR DEMOCRACY

Serbia’s struggle for democracy began with the fall of Communism in the late 1980s and the wars that followed the violent breakup of the former Yugoslavia. Strongman Slobodan Milosevic’s warmongering in the 1990s turned Serbia into an international pariah, while NATO bombed the country in 1999 to stop the war in the breakaway province of Kosovo.

Milosevic was ousted in 2000 by pro-democracy parties openly backed by the West, setting the stage for reintegration into the international community and the start of democratic reform.

“It wasn’t good enough … but you still had a country where things started to resemble European standards,” said Dragan Djilas, a former mayor of Belgrade who is now one of the leaders of a pro-European coalition that is challenging Vucic’s Serbian Progressive Party in parliamentary and local elections on Dec. 17.

“We had free elections, we had the possibility of change (of power) in elections … No one threatened you for thinking differently and no one blackmailed you,” he said. “Today’s Serbia ... would not even be allowed to become a candidate for EU membership.”

Public support in Serbia for joining the EU stands at about 40%. Under the circumstances, pro-democracy activists say, that counts as a success.

EU DEALS CAUTIOUSLY WITH SERBIA

The EU’s enthusiasm for enlarging the bloc waned after 2013, when Serbia’s neighbor Croatia became the newest country to join. The EU had accepted 13 new member states since 2004, most of them in Central and Eastern Europe and needing substantial injections of financial support. The prospect of taking in additional members who would be a drain on the EU budget was hardly enticing.

And then there was Kosovo, which declared independence from Serbia in 2008. The move was not recognized by Belgrade — nor by some EU member countries with separatist movements of their own, such as Spain, or with close ties to Serbia, such as Cyprus and Greece. The wars of the 1990s had subsided, but Serbia’s unresolved final borders left a huge question mark over its suitability to join the EU.

The EU paid lip service to further enlargement with regular membership updates but made little response as Vucic steadily took over the levers of power in Serbia. Over the years, he and his authorities installed loyalists in key government positions, including the military and secret service, and imposed control over the mainstream media while stepping up pressure on dissent.

“Problem is that all this happened during the EU’s watch,” Medjak said.

With war raging in Ukraine, analysts say the EU has been careful not to push Serbia further away, even as Belgrade refused to join Western sanctions against Moscow. The U.S. and EU have worked closely with Vucic to try to reach a deal in Kosovo, where tensions at the border have threatened regional stability.

ANTI-DEMOCRATIC TIDE RISES

Vucic dismisses criticism that his government has curbed democratic freedoms while allowing corruption and organized crime to run rampant. Pro-government tabloids and state-run media, such as the broadcaster RTS, give scant coverage to the opposition, while dozens of rights groups have faced investigations into their finances.

Vucic regularly blasts Djilas and other opposition leaders as enemies of the state and “thieves” who are taking instructions from Western embassies. Mainstream pro-government media give them no opportunity to respond to the allegations.

During the wars of the 1990s, Vucic was an extreme nationalist who supported Milosevic’s aggressive policies toward non-Serbs. After Milosevic fell, Vucic reinvented himself as a pro-European, helping to found the Serbian Progressive Party in 2009 and pledging to take the country into the EU.

He never delivered on his promises.

Since 2014, Serbia has dropped down the international rankings on democracy. Reporters Without Borders says journalists are threatened by political pressure, while Transparency International ranks Serbia below most countries in the region when it comes to fighting corruption.

In recent years, Serbia's ruling party has "steadily eroded political rights and civil liberties, putting pressure on independent media, the political opposition, and civil society organizations," said the monitoring group Freedom House in its most recent report.

Serbia’s Ministry for European Integration did not grant an interview to the AP, citing the upcoming elections. EU officials also declined to comment.

While activists lament the stagnation of its EU membership bid, Serbia recently received a strong vote of confidence from Italy’s far-right premier, Giorgia Meloni.

Flanked by Vucic, Meloni praised his statesmanship, saying, “Europe isn’t a club who decides who is and who is not European.’’

A CHALLENGE TO SERBIA'S PRESIDENT

In recent months, Vucic has faced a new challenge to his authority. In May, 19 people, many of them children, were killed in two back-to-back mass shootings. The attacks shocked the public, galvanizing protests against a climate of fear and intolerance promoted by the ruling elite.

As he has done in the past when he felt he was losing his grip on power, Vucic called snap parliamentary and local elections for dozens of Serbian towns and cities, including Belgrade.

In response, the protesters formed their own electoral coalition, fielding candidates across the country. Vucic himself is not a candidate this time, but the opposition has hopes of denting his authority by taking control of some local councils.

Political activist Vostinic, who braved pressure from the ruling party in Kraljevo to lead protests there, said Serbia’s society had taken a wrong turn, allowing “people with bad intentions to fill in the gap.”

The EU, he said, is no longer an ally in defending its own values but has focused on economic and other interests, more concerned about countering Russia and China.

Public disappointment is such that “we who support the respect of European values are starting to feel uneasy," Vostinic said.

Opposition leader Djilas is even harsher, saying that “EU politicians largely are allies of Aleksandar Vucic.”

“As a student, my dream was Serbia as a part of Europe, of the European Union,” he said. “I have to admit that now the dream is sometimes turning into a nightmare.”

___

AP writer Frances D’Emilio contributed from Rome.

____

This story, supported by the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, is part of an ongoing Associated Press series covering threats to democracy in Europe.

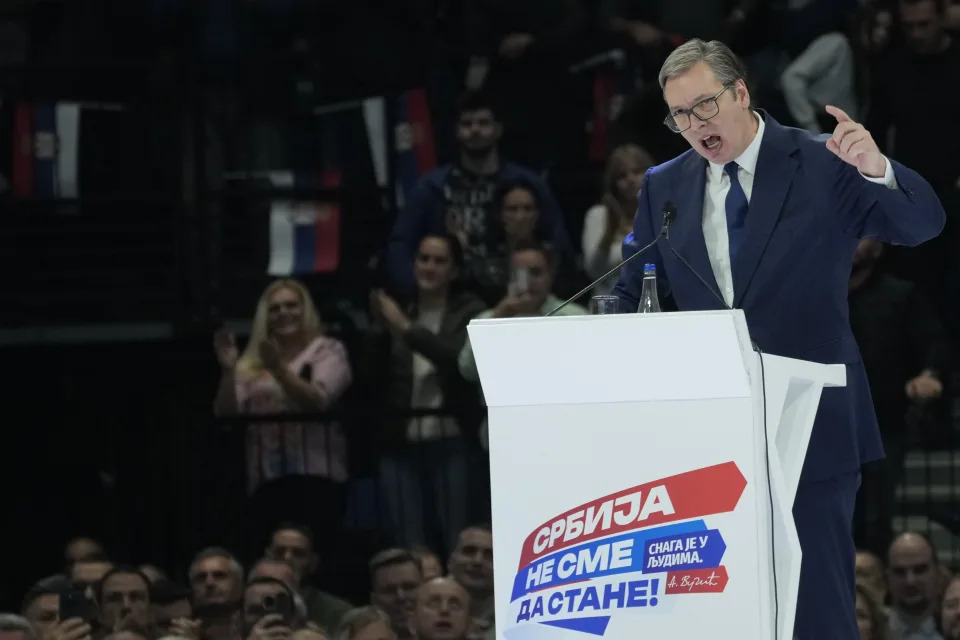

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic speaks during a pre-election rally of his ruling Serbian Progressive Party in Belgrade, Serbia, Saturday, Dec. 2, 2023. When Serbia formally opened membership negotiations with the European Union, back in 2014, it was a moment of hope for pro-Western Serbs, eager to set their troubled country on an irreversible path to democratization. Those days are long gone. Now, they feel betrayed, both by the government and the EU.