Lessons of the Peloponnesian War

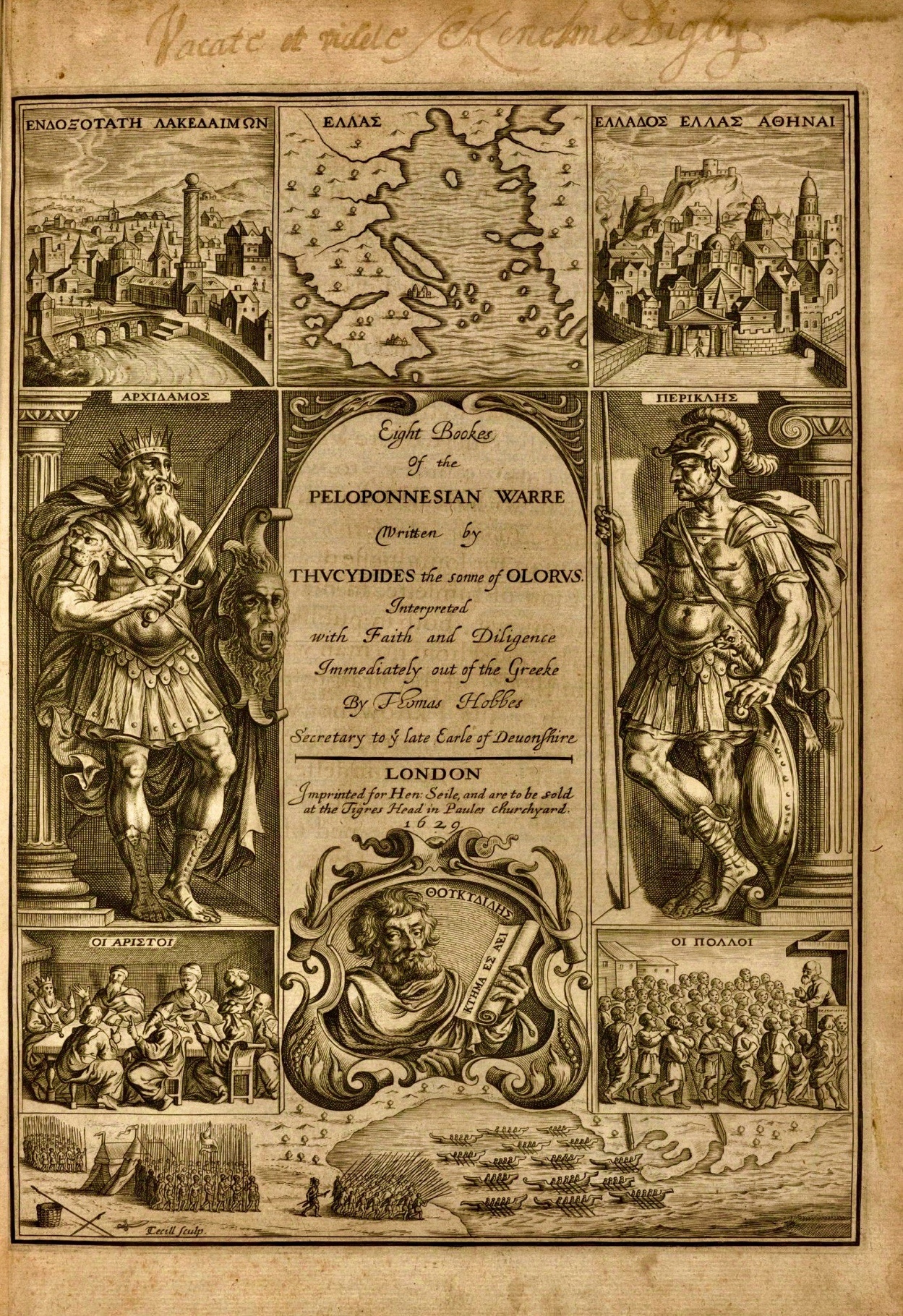

Title: Eight Bookes of the Peloponnesian Warre written by Thucydides. Interpreted by Thomas Hobbes. London, 1629. Houghton Library, Harvard. Public Domain

The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides is an awesome story about the ancient Greeks. But the story is more than a war report. It opens the doors into the nature of the Greeks, their culture, their greatness, and fatal weakness — their conviction each was better than the rest, each polis (city-state) thinking itself the Olympic champion in a perpetual Hellenic struggle. And in the case of the two most powerful poleis, Athens and Sparta, if they could not rule the other, they would stay fiercely independent. But in war they became barbarians — and worse. All or nothing. They fought persistently, with vigor, courage, brutality, to the last man.

This was real tragedy written all over the Greek world. That’s why the theater was so fundamental to the Greeks. The tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides fought the Greeks’ greatest intellectual and spiritual battles. The tragic poets desperately tried to make the Greeks rethink their killer impulse. Sophocles and Euripides never ceased reminding them they were one people worshipping the same gods, kept together by the same divine traditions. And Aeschylus, probably because of the Persian invasion of Greece, always reminded them that it was better to die on one’s feet than live on one’s knees. Yes, freedom was the message of Aeschylus and Greek tragedy. But the Peloponnesian War blurred tragedy and freedom. In fact the Peloponnesian War brought tragedy nearly to an end since the conflict itself became the new tragedy. Could the carnage of the war be explained as a result of the Spartans’ fear of Athenians’ growing power? Thucydides was certain of that. But it was the Spartan ambassador Melesippos who predicted that the Peloponnesian War would bring nothing but grief to the Greek people.

In some twenty-seven years, the Athenians and the Peloponnesians devastated Greece proper, the Greek poleis of Ionia (Asia Minor), the islands of the Aegean and Ionian Sea, and Sicily. They also practiced biological warfare with their persistent burning and destroying of each other’s land and crops. Moreover, they slaughtered each other by the thousands, enslaved and sold their women and children by the thousands, brought barbarians to their politics and warfare — and the Spartans and the Peloponnesians made the Persians, the Greeks’ ancient enemies, their pay masters. Indeed, it was the Athenian general Alcibiades who urged Persian leaders to keep funding Greeks killing Greeks.

Clearly, the Peloponnesian War was the beginning of the end of Greek political freedom. With Athens prostate in 404 BCE, the dream of a united Hellas remained a dream for another sixty-eight years until 336 BCE when Alexander the Great brought all Greeks under his command to fight the Persians. But by that time, not merely Athens but Sparta and Thebes and Argos — the greatest of Greek poleis — were exhausted. War, particularly their nearly ceaseless fratricidal conflicts, had sapped their military and political power. No wonder that the Greek historians Polybius and Plutarch, one living in the second century BCE and the other during the second century of our era, spanning between them four centuries of Roman domination of Greece, did not hate Rome. They knew that Rome extinguished Greek political independence and freedom. But they also had studied the history of the Peloponnesian War. Rome was the enemy, but Rome had stopped the endless antagonisms and often bloody civil wars. Polybius was quite loyal to Rome.

Yet the fifth century BCE, the last 27 years of which were disrupted by the Peloponnesian War, was so much a century of original creation in political theory, democracy, medicine, architecture, science, tragedy, theater, sculpture, art, literature, history, and Greek culture in general, that, despite the Peloponnesian War’s devastation, the Greeks were preeminent in Europe for nearly another 800 years down to the making of Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century of our era.

War and light

Plato and Aristotle, center, in the School of Athens by Raphael, 1511. Public Domain

Plato and Aristotle flourished in the fourth century BCE, the century after the end of the Peloponnesian War. But the overall achievements of the fifth century were of such magnitude that even the ferocity of the Peloponnesian War was probably subsumed into that greatness. The fifth century was a phenomenon so unique in Greek and global history that the English classical scholar Peter Levi rightly saw it as “an explosion of light which affected everything and still does so today [1980]. Europe is the result and Greece is the key.”[1]

The light (from craftsmanship, science, technology, art, and architecture and theater) reflects honest efforts of the Greeks to set their civilization on more solid foundations. But the darkness of the Peloponnesian War clouded, to some degree, that light.

The Peloponnesian War was like angry Poseidon threatening to sink the country under the waters of the Mediterranean. Xenophon, who gave us the narrative of the carnage of the last seven years of the Peloponnesian War, was a pupil, like Plato, of Socrates, an Athenian patriot and moral philosopher that fought in the war defending Athens. In fact Socrates was the only elected citizen in the Athenian Assembly in 406 BCE who dared to vote against killing the ten generals because they failed to prevent the drowning of several Athenian sailors after a victorious naval engagement with Sparta near Lesbos. This was also the year, 406 BCE, that the Athenians had turned with vengeance, for the second time, against Alcibiades, Socrates’ beloved pupil.

Democracy as usual, aristocracy, monarchy

Xenophon and Plato loved Socrates. They also loved a united Hellas. Their writings constitute a great documentary evidence of the Hellenic light that exploded in Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. They wrote about nearly everything. Yet Plato’s Republic, the political masterpiece of Greece’s greatest moral philosopher, and Xenophon’s Cyropaideia, a historical novel, have something in common. They are the direct consequence of the Peloponnesian War. They searched for alternatives to the failing democratic institutions of Athens that put Socrates to death. They are also trying to expand Greek political theory so that the Greeks could build a unified Hellas. Plato created an ideal polis that filled the gaps of human imperfection and corruption in a democracy. The best, the aristoi, are the aristocratic rulers in Plato’s Republic, not the average citizen of a Greek democratic polis, all too often tempted to overstep the bounds of justice and public interest. Xenophon’s Cyropaideia took the founder of the Persian Empire, Cyrus the Great, and made him the ideal ruler of a vast country. Both Plato and Xenophon witnessed firsthand the catastrophic effects of the Peloponnesian War. They were angry and bitter with the unwillingness and inability of the Greeks to form a Hellenic state. The Republic and Cyropaideia end instability in the Greek world, one with a polis governed by men who love wisdom, philosophers, and the other with a virtuous, compassionate, and just ruler. Plato and Xenophon were not enemies of democracy. They were enemies of the disintegrating forces in the Greek world that made war inevitable. Their proposals were designed not as models but as inspiration to expand the theoretical political horizon of the Greeks beyond the self-destructive confines of the jealous polis. After all, the Athenians, the Spartans, the Corinthians, the Thebans and the Macedonians were convinced they were the very best of the Greek people that had to rule the rest of the Greeks. Set on that narrow path, they could not see their enemies.

The Persian invasion of Greece caught most of them by surprise. And while the Athenians, Spartans, Plataeans and some other Greeks defeated the Persians, the Thebans joined the Persians against the Greeks. With the Republic and Cyropaideia, Plato and Xenophon sounded the alarm bells that Greece had to rethink its political life, or it would lose its freedom. Plato was a moral philosopher who, naturally, concluded that men of ethical standards and deep knowledge, men like him, would provide a more secure future for the Greek people. And Xenophon used his military experience and understanding of the Persians to suggest that, perhaps, the Greeks had to modify and subordinate the political independence of the polis to a broad Hellenic interest – a unified Hellas — that included the interest and security of all Greeks.

Greece in 2024

Modern Greece includes most Greeks, but the country is neither unified nor independent. The loss of Greek freedom to the Romans in 146 BCE, the Christianization of Hellas in the fourth century and after, the occupation of the country by Mongol Turks in 1453, and Western influence after the liberation of Greece in the 1820s by Greeks themselves, are forces shaping the future of Greece.

The German occupation of Greece, April 1941-October 1944, nearly annihilated the country. And because America embraced the defeated Germans for the Cold War against the Soviet Union / Russia, Greece never received the war reparations from Germany. This was an additional blow to the destruction of the country from the civil war in Greece, 1945-1949, cooked by Germany and England. The German debt and reparations owned to Greece are approximately one trillion euros. If Greece had those substantial funds, the country would have avoided the humiliating debt that, starting in 2010, during the Obama administration, all but made the country a colony of Germany, the European Union and the United States. And because the US is still fighting its Cold War against Russia, it probably forced the governments in Greece to do the bidding of its archenemy, Turkey.

This unpatriotic policy, due to external influences on the government in Athens, has weakened the imported democracy in Greece, which is completely undemocratic. The Prime Minister acts like a monarch, nay a tyrant. Turkey keeps humiliating Greece and Greece, doing the bidding of US / NATO, keeps deceiving its citizens with propaganda while sending defeatist messages to Turkey and the world.

Is anybody reading Thucydides?

This is opening the appetite of Turkey, especially after the US in 1974 made its invasion of Cyprus possible. What the US and NATO fail to understand is that Cyprus is a Greek island, extremely ancient with sophisticated Greek civilization. Britain prevented the union of Cyprus to Greece. In fact, England brought Turkey back to Cyprus and urged it to launch its vicious 1955 pogrom against 85,000 Greeks of Istanbul. Like the Peloponnesian War, this story has consequences. Greeks don’t forget their friends and their enemies. NATO’s blindness for ephemeral if ill chosen priorities is bound to backfire. You cannot keep historical enemies in the same house. The house will collapse. In other words, Turkey does not belong in NATO, Europe or any other civilized conclave or organization. Europeans and Americans, at least their educated elites, know that Turks have enslaved Europeans, including Greeks, for centuries. They have been employing genocide and atrocities as conventional weapons to terrorize the non-Turks. So why has the US recruited them for their holy war against Russia? Don’t they know the Turks have no friends outside the Islamic world? The Turks besides would not fight Russians because the Russians defeated then repeatedly in the past. But aside from that, supporting Turkey you tell the Greeks you are against them. But the Greeks gave the US and Europe science, technology, architecture, law, democracy, in short, civilization.

So, neither Greece, in its modern resurrection, nor Europe, nor the US have learned anything from Thucydides. Perhaps, the Peloponnesian War just happened? Of course, not. Sparta, like America in 2024, went to war because it feared the rising power of Athens. Similarly, the US must feel uncomfortable with a strong Russia, a giant of a country recovering from the disbanding of its empire. However, the US ignores the fallout of the Peloponnesian War at its own peril. In fact, the peril is already threatening the country from within. Former President Trump, who should be in prison for his January 6, 2021 effort to overthrow the government, is running for president, again! But the administration of President Biden ignored Trump and focused on fighting Russia through Ukraine. Moreover, Biden is funding Israel in its deadly wars against Palestine and Lebanon and Iran. This folly may bring Trump to power, a calamity for democracy, the American people, the natural world, and possibly the planet.

NOTES

1. Peter Levi, Atlas of the Greek World (New York: Facts on File, 1980), p. 10. ↑