LONG READ

[By Mikael Lind, Wolfgang Lehmacher, Sandra Haraldson, Ernst Hoestra, Boris Kriuk, Richard van der Meulen, and Mark Scheerlinck]

Introduction: When Traditional Approaches Fall Short

Transport and logistics have always hinged on seamless coordination. Moving goods from point A to point B involves a complex web of actors, including shippers, freight forwarders, carriers, terminal operators, port authorities, customs officials, warehouse operators, and first-mile and last-mile delivery providers. Cargo is typically handed over in nodes from one controlling party to another. It is in these nodes that changes can be applied to the trajectory of the cargo. This requires collaboration. Traditionally, each participant has managed their role in isolation, sharing information only when necessary, primarily through bilateral channels.

This model has sustained the industry for decades, yet it increasingly reveals its limitations. In today’s volatile and interconnected world, where disruptions have shifted from exceptions to expectations, fragmented and linear information flows create blind spots, delays, inefficiencies, and fragility.

The solution transcends mere technological upgrades; it demands a fundamental reimagining of how we organize and interpret vast, disparate streams of supply chain data. Rather than scattered exchanges, what’s needed is a collaborative data-sharing regime that imposes order upon chaos, delivering shared visibility and situational awareness across the entire ecosystem. Such a framework empowers actors not just to be informed, but to act decisively, converting raw data into strategic insight. The result: enhanced coordination, resilience, and performance.

This is an ambition that the Virtual Watch Tower (VWT), a multi-stakeholder community co-creating a digital, federated architecture and solution as a public good, pursues in its approach to data sharing for better disruption and carbon footprint management.

The Inherent Limits of Traditional Data Sharing

In the traditional landscape, data exchanges are direct and narrowly focused, typically confined to transactions between two actors. A shipper updates a carrier. A carrier informs a forwarder. A terminal operator alerts a trucking company. Each communication serves immediate operational needs, with a transactional brevity that sacrifices holistic understanding.

This approach bears three critical shortcomings:

- Fragmentation: Each participant sees only a sliver of the entire operation, isolated snapshots rather than a cohesive panorama.

- Inefficiency: Data is redundantly transmitted across numerous bilateral links, leading to duplication and discrepancies.

- Latency: In the face of natural disasters, strikes, congestion, system outages, or geopolitical shocks, actors struggle to access timely and comprehensive data, hampering coordinated responses.

The consequence is a fragmented patchwork of data streams, leaving stakeholders “starving for data but lacking insight.”

Embracing a Collaborative Data Sharing Regime

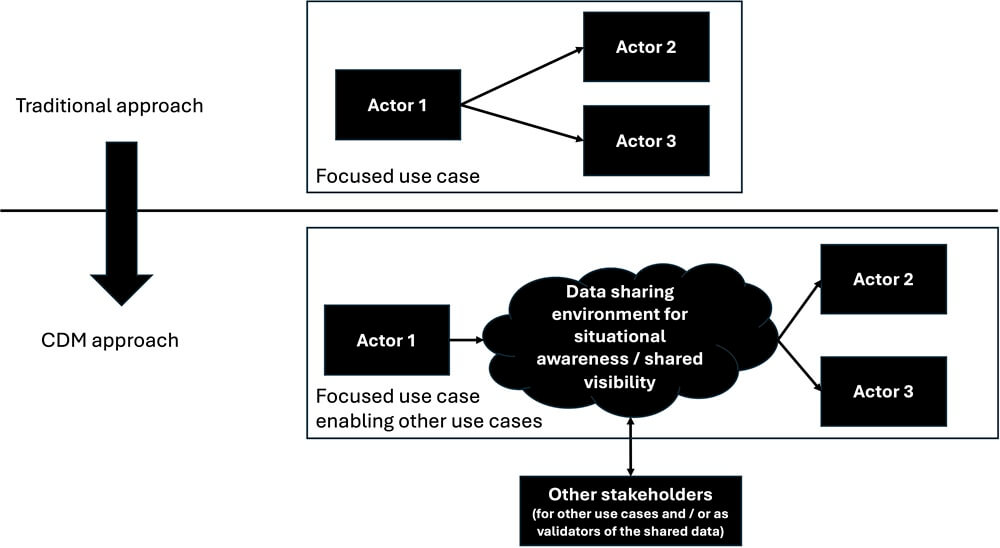

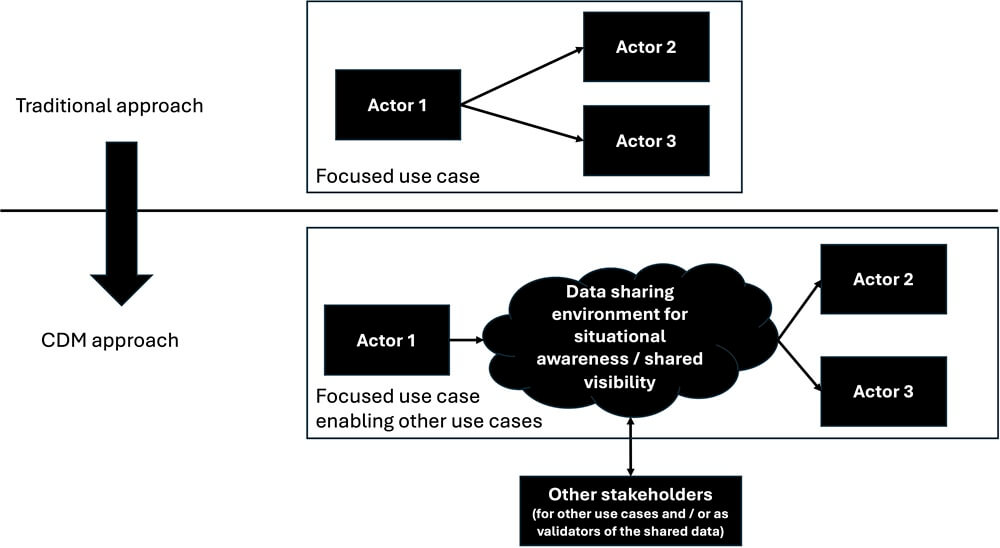

A transformative alternative lies in a Collaborative Decision-Making (CDM) approach. Instead of Actor #1 transmitting updates separately to Actors #2 and #3, data enters a shared, trusted pool accessible to all authorized participants (Figure 1). This shift from bilateral exchanges to an ecosystem-wide platform enables real-time shared visibility.

Figure 1: Fundamentals on Data Sharing: From bilateral to ecosystem-based data exchanges

This methodological leap unlocks profound benefits:

- Unified situational awareness: Everyone views the same data, smoothing misalignments and fostering shared understanding.

- Scalability: Data is shared once and consumed by many, eliminating inefficiencies.

- Resilience: Early detection and coordinated response to disruptions become routine.

- Trust and sovereignty: Each actor maintains control over their data, dictating access within an interoperable and fair framework.

In essence, collaboration brings clarity and meaning to the raw data flowing through supply chains.

A Four-Layer Framework to Bring Order and Insight

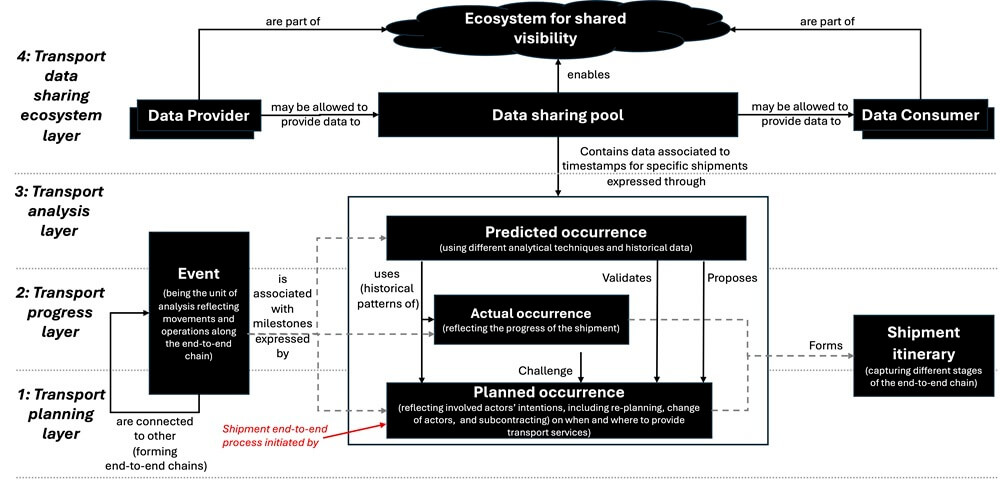

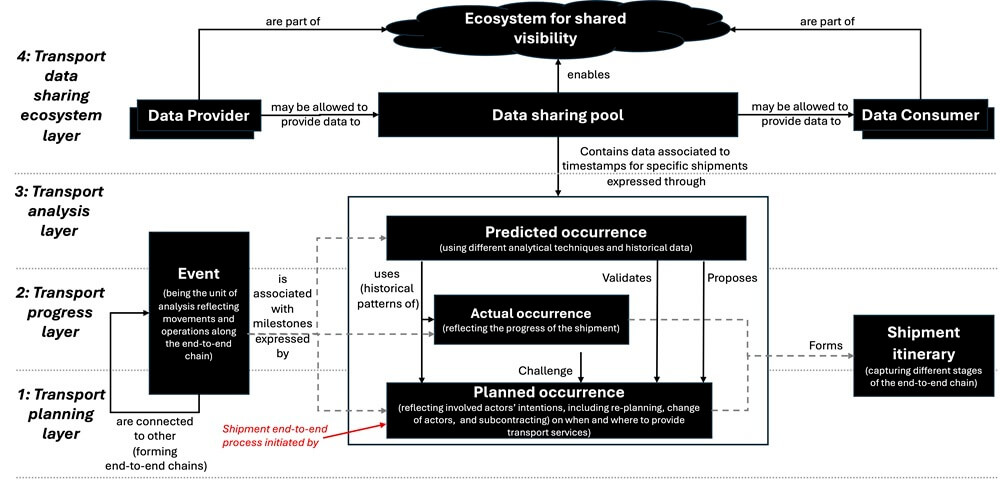

At the core of this new regime is a systematic model (Figure 2) that organizes fragmented information into three interlocking layers, which are wrapped within a fourth evolutionary layer that enables secure and trusted ecosystem-wide data sharing. Each layer enriches data with context and purpose, turning raw signals into orchestrated decisions.

This framework relies on establishing common semantics at each layer, ensuring that data shared between planning, progress, and analysis is coherent and interpretable by every actor. Only with agreed-upon definitions and structures can insights be generated and acted upon reliably across the supply chain.

Figure 2: Layered data sharing framework

1. Transport Planning Layer – Sharing Intentions

The planning layer looks forward. It captures actors’ intentions, the planned container movements, vessel unloading, and truck dispatches, offering a dynamic view of expected operations. Shared plans enable proactive coordination: for example, a delay of a ship leads to a new plan and prompts terminal berth reallocation and trucking schedule adjustments. The value of the shared plans also depends on standardized representations of intentions and schedules.

2. Transport Progress Layer – Documenting What Has Happened

This layer logs real-time data, including timestamps of events such as “container loaded,” “vessel departed,” or “truck arrived at gate.” Leveraging Internet-of-Things (IoT) sensors and system signals, it constructs a reliable, shared timeline, replacing isolated updates with a common factual record. Documenting events requires agreed-upon event codes and timestamp formats.

3. Transport Analysis Layer – Illuminating Insights

Here, analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) synthesize data from planning and progress layers to simulate deviations, estimate delays, forecast arrivals, and even compute emissions. This layer distils streams of raw data into actionable insights, offering foresight, risk awareness, and performance metrics that anchor decision-making. Helpful analytical insights arise from consistently formatted and meaningful raw data.

4. Transport Data Sharing Ecosystem Layer – Wrapping and Enabling Across Layers

Surrounding and enabling these three layers is the data sharing ecosystem itself. This outer layer ensures that data flows securely, transparently, and with trust throughout the entire network. It enforces access controls and sovereignty policies, allowing each participant to determine who sees what, while supporting seamless interoperability and fairness. A trusted sharing environment must enforce semantic consistency as a basis for interoperability.

This ecosystem is not merely a container but a living framework that facilitates collaboration across planning, progress, and analysis, amplifying the value created within each layer and fostering resilient, coordinated supply chain networks.

Due to this systemic approach, the integrity of data management also enables a fully controlled Return Cycle, which, based on current Producer Responsibility rules, should be considered a major additional benefit.

How the Layers Synchronize: From Fragmentation to Elegance

Imagine a container moving from a factory in Asia to a warehouse in Europe:

- The planning layer captures the intended shipping schedule.

- As the shipment proceeds, the progress layer records the container’s loading onto a vessel and subsequent real-world events.

- The analysis layer continuously compares the shipping plan against actual progress, predicts delays, recalculates arrival times, and updates emissions estimates.

Throughout this cycle, the data sharing ecosystem secures and governs the data flow to the port, trucking company, and other parties downstream , ensuring that access and usage rights are respected while enabling authorized actors to consume and engage with the same accurate and timely information.

This orchestration transforms once fragmented, reactive data into a continuous, coherent, and actionable stream.

Trust Reinforced by Data Sovereignty

Fear of losing control has long stifled data sharing. This regime addresses such concerns head-on: sovereignty is preserved. Each actor defines what to share, with whom, and under which conditions, supported by distributed platforms such as federated systems and blockchain.

No single entity dominates; instead, information is structured and shared across the ecosystem with embedded permissions. Trust flourishes when fairness and transparency underpin data governance.

Why Action Is More Urgent Than Ever

Today’s supply chains generate unprecedented data volumes. Every scan, movement, and transaction emits digital signals. Yet without structure, this mass merely manifests as noise.

Simultaneously, global volatility, from pandemics to geopolitical tensions and climate events, demands swift, coordinated reactions. The solution IS NOT more data, but smarter, better-organized data.

The four-layer framework provides a roadmap, turning disjointed signals into shared understanding and transforming data chaos into resilient coordination.

Aligning Incentives for Sustainable Data Sharing

Incentives must align across participants for this model to succeed. The logical starting point is the shipper, whose inputs, like shipment itineraries and booking details, anchor the shared structure.

Operators, terminals, and carriers then contribute data as part of service fulfilment. This reciprocity creates mutual value: clarity generated by others enhances each actor’s operations.

Over time, structured data-sharing will evolve from a competitive advantage to an industry imperative.

Conclusion: From Data Fragmentation to Meaningful Coordination

The logistics sector has historically amassed an abundance of data but suffered from a paucity of shared understanding. Traditional fragmented approaches yield isolated signals that obscure the bigger picture.

What is required goes beyond technology: a fundamentally new way to structure, interpret, and act on existing data.

The collaborative four-layer model achieves this by:

- Aligning plans: sharing intentions.

- Anchoring progress: documenting reality.

- Extracting meaning: illuminating insight.

- Enabling trust: facilitating secure, sovereign data sharing across the ecosystem.

Together, these layers weave disconnected updates into a shared narrative, trusted and actionable by all participants.

A vital first step is cultivating shared situational awareness. Structured data enables actors to perceive the broader ecosystem and receive early alerts about emerging disruptions, such as delays, capacity shortages, or congestion, empowering proactive responses.

However, structure alone is insufficient. The value emerges when visibility translates into action: rebooking when capacity tightens, alternative routing amid congestion, and emissions calculators to align disruption management with sustainability goals. These services transform awareness into resilience.

The message is unequivocal: collaboration is not optional; it is essential—a vision lived by VWT. Only through collective order, insight, and trust can supply chains transcend fragmented data to achieve meaningful coordination, moving from reactive firefighting toward proactive, resilient logistics. By moving data towards a public good, VWT translates data-sharing into a solution that benefits all.

About the authors

Mikael Lind is the world’s first (adjunct) Professor of Maritime Informatics engaged at Chalmers and Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE). He is a well-known expert frequently published in international trade press, is co-editor of the first two books on Maritime Informatics and is co-editor of the book Maritime Decarbonization.

Wolfgang Lehmacher is a global supply chain logistics expert, partner at Anchor Group. The former director at the World Economic Forum, and CEO Emeritus of GeoPost Intercontinental, is an advisory board member of The Logistics and Supply Chain Management Society, ambassador F&L, and advisor Global:SF and RISE. He contributes to the knowledge base of Maritime Informatics and co-editor of the book Maritime Decarbonization.

Sandra Haraldson is Senior Researcher at Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE) and has driven several initiatives on digital collaboration, multi-business innovation, and sustainable transport hubs, such as the concept of Collaborative Decision Making (e.g. PortCDM, RailwayCDM, RRTCDM) enabling parties in transport ecosystems to become coordinated and synchronised by digital data sharing.

Ernst Hoestra is the CEO of Erasmus Enterprise, has 25 years of senior leadership experience at companies including TNT, Pitney Bowes, and Cycleon (now ReBound Logistics), where his team introduced game changing technology to facilitate global returns management processes. He is also an investor, advisor, board member, and lecturer in innovation, strategy, and entrepreneurship.

Boris Kriuk is Chief of AI at Strevio Limited, head of R&D at Sparcus Technologies Research Group, as an active member of Computer Vision Foundation, Association of Computing Machinery, honoured associate member at London Journal Press and Speaker at Computer Graphics Society, he has years of experience in AI for Logistics and Supply Chain research and innovation.

Richard van der Meulen is a global supply chain thought leader with 20+ years in international trade and logistics. As Vice President at Infor Nexus, he advances AI-powered cloud solutions and industry-wide collaboration. A frequent keynote speaker and strategist, he champions data sharing to enable resilient, digitally connected supply chains.

Mark Scheerlinck is co-founder of Chasqee BV, a young IT company creating innovative solutions for supply chain visibility and orchestration. As 4th generation in the port of Antwerp, with extensive experience in managing, creating and M&A of maritime supply chain companies, the practical experience is combined with vision and IT. A broad network in supply chain and ample experience as a speaker in EU context complement the drive to innovate.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.