Trump urged Zelenskiy to cut a deal with Putin or risk facing destruction, FT reports

Reuters

Sun, October 19, 2025

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskiy meets with U.S. President Donald Trump (not pictured) over lunch in the Cabinet Room at the White House in Washington, D.C., U.S., October 17, 2025. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

(Reuters) -U.S. President Donald Trump urged Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy to accept Russia's terms for ending the war between Russia and Ukraine in a White House meeting on Friday, warning that President Vladimir Putin threatened to "destroy" Ukraine if it didn't comply, the Financial Times reported on Sunday.

During the meeting, Trump insisted Zelenskiy surrender the entire eastern Donbas region to Russia, repeatedly echoing talking points the Russian president had made in their call a day earlier, the newspaper said, citing people familiar with the matter.

Ukraine ultimately managed to swing Trump back to endorsing a freeze of the current front lines, the FT said. Trump said after the meeting that the two sides should stop the war at the battle line; Zelenskiy said that was an important point.

The White House did not immediately respond to a Reuters request for comment on the FT report.

Zelenskiy arrived at the White House on Friday looking for weapons to keep fighting his country's war, but met an American president who appeared more intent on brokering a peace deal.

In Thursday's call with Trump, Putin had offered some small areas of the two southern frontline regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia in exchange for the much larger parts of the Donbas now under Ukrainian control, the FT report added.

That is less than his original 2024 demand for Kyiv to cede the entirety of Donbas plus Kherson and Zaporizhzhia in the south, an area of nearly 20,000 square km.

Zelenskiy's spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for comment sent outside business hours on whether Trump had pressured Zelenskiy to accept peace on Russia's terms.

Trump and Putin agreed on Thursday to hold a second summit on the war in Ukraine within the next two weeks, provisionally in Budapest, following an August 15 meeting in Alaska that failed to produce a breakthrough.

(Reporting by Anusha Shah in Bengaluru; editing by Philippa Fletcher)

Trump’s Private Blow-Up With Zelensky Revealed

Sun, October 19, 2025

Win McNamee / Getty Images

Another meeting between President Donald Trump and President Volodymyr Zelensky has reportedly ended with a fiery shouting match—this time behind closed doors.

Trump was pressuring his Ukrainian counterpart to accept Russia’s terms for a ceasefire during an explosive White House meeting on Friday, according to the Financial Times, reportedly telling Zelensky that Russia would “destroy” Ukraine if he didn’t agree.

Multiple sources told the outlet that the meeting—where Zelensky was hoping, but ultimately failed, to secure long-range Tomahawk cruise missiles—quickly descended into a “shouting match” with “cursing all the time.”

Donald Trump hosted President Zelensky at the White House this summer to discuss a peace deal between Russia and Ukraine. / Alex Wong / Getty Images

According to sources, the scene resembled that of Zelensky’s infamous Oval Office visit in February, where he was was berated by Vice President JD Vance for not voicing enough thanks for U.S. help in the war against Russia, before a shouting match ensued.

Zelensky was also accused of being “disrespectful” to the U.S. for not wearing a suit and tie and was reportedly all but forced out of the White House.

This time, Trump demanded that Zelensky surrender the entire Donbas region to Russian President Vladimir Putin, sources said.

European officials told the Financial Times that Trump repeated many of Putin’s talking points “verbatim” during the meeting, telling Zelensky he was losing the war and that “If [Putin] wants it, he will destroy you.”

The outlet reported that “Zelenskyy was very negative” after the meeting, according to one official, and that European leaders were “not optimistic but pragmatic with planning next steps.”

The tense encounter came after Trump reportedly spoke with Putin by phone and seemingly welcomed the Russian dictator back in his good graces.

On Truth Social, the dictator-curious Trump wrote Putin congratulated him on the “Great Accomplishment of Peace in the Middle East,” and suggested that his “Success in the Middle East will help in our negotiation in attaining an end to the War with Russia/Ukraine.”

He added that “High Level Advisors” from the United States and Russia would meet next week at an as-yet-undisclosed location, and that he would then meet personally with Putin in Budapest, Hungary, “to see if we can bring this ‘inglorious’ War, between Russia and Ukraine, to an end.”

Trump rolled out the red carper for Russian President Vladimir Putin in Anchorage, Alaska, in August. / Contributor / Getty Images

Ironically, the talks are set to take place in the same city where Russia once signed an agreement promising it would never invade Ukraine.

When asked who chose to hold the meeting in Budapest, a location with great historical significance to both Russia and Ukraine, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt simply told HuffPost, “Your mom did.”

The Daily Beast has reached out to the White House for comment.

Trump says he expects Putin to keep some Ukrainian land in latest U-turn: ‘I mean, he’s won certain property’

John Bowden

Sun, October 19, 2025

Donald Trump told a Fox anchor that he expected Ukraine to make territorial concessions in any peace agreement his administration could potentially orchestrate between Kyiv and Moscow to bring the nearly four-year war between Russia and Ukraine to an end.

In an interview that aired on Sunday Morning Futures with Maria Bartiromo, the U.S. president indicated that under the terms of a deal authored by the White House, Russia would likely be allowed to retain territory it has occupied since February of 2022.

Trump spoke with Russia’s Vladimir Putin by phone for two hours on Thursday, then met the following day with Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House where all public signs of the tension between the two men which had erupted at a meeting this spring had vanished. Privately, however, the Financial Times reported on Sunday that the conversation between Trump and Zelensky repeatedly devolved into a “shouting match” with the U.S. president warning his counterpart that Russia would “destroy” his country if he didn’t accept territorial concessions.

On Sunday, Bartiromo asked Trump whether he’d gotten a sense from Putin during that conversation that he was “open to ending this war without taking significant property from Ukraine?”

Cutting in, Trump responded, “I did, I did.” But his answer shifted as the Fox host finished her question and asked whether Putin would return Ukrainian territory.

Donald Trump told Fox News that Ukraine would likely need to recognize Russian territorial gains in a ceasefire (Sunday Morning Futures)

“Well, he's gonna take something. I mean, they fought and, he, uh, he has a lot of property. I mean, you know ... he's won certain property,” Trump said, before sarcastically quipping: “You know, we’re the only country that goes in, wins a war and then leaves.”

This is a sharp departure from the aggressive rhetoric the U.S. president was pushing in late September, when he was urging Ukraine to continue fighting until it had regained all of its lost territory. Ukraine hasn’t signalled a willingness to recognize Russian claims to the Crimean and Donbas regions, including the cities of Donetsk and Mariupol.

As peace talks with Russia stalled over the summer, Trump hardened his stance against Moscow and seemed to be coming around to an assumption that many in Washington’s foreign policy establishment have held since 2022 — that Vladimir Putin isn’t interested in peace without significant further Ukrainian concessions beyond what has played out on the battlefield. In the past week, however, Trump has renewed his efforts aimed at securing a peace agreement as he has become emboldened by the shaky truce struck by the White House between Israel on Gaza. On Sunday, that ceasefire seemed to be wavering as both sides traded accusations of violations.

In September, Trump wrote that Ukraine could “take back their country in its original form and, who knows, maybe even go further than that!” in a Truth Social posting. In other statements, he signaled interest in mounting further pressure on Moscow, including through a congressional sanctions package or the sale of further arms such as Tomahawk cruise missiles to Ukraine.

The Tomahawk, much sought after by Mr Zelensky, has a range of about 1,600km (995 miles) but experts warned that it could take years to provide the equipment and training necessary for Ukraine to use them effectively. The Ukrainian leader made the request to Trump during his visit to the White House on Friday; Zelensky sees further U.S. military aid including the delivery of new weapons systems as the most effective course of action for putting pressure on Russia to return to the negotiating table.

“Yeah, I might tell him [Putin], if the war is not settled, we may very well do it. We may not, but we may do it,” the president said earlier in October. “Do they want to have Tomahawks going in their direction? I don’t think so.”

He backed off that latter idea after threats from Russia and his conversation with Putin on Thursday, and with his latest statement will likely leave many in Washington wondering whether his position truly evolved at all. Putin called the issue a red line for U.S.-Russia relations, while his close ally Aleksandr Lukashenko, president of Belarus, warned it would risk “nuclear war” in Europe.

After his conversation with the Russian leader Trump also agreed to meet with Putin in Budapest on an undisclosed upcoming date.

After Zelenskyy meeting, Trump says Ukraine, Russia should declare victory

Sat, October 18, 2025

Washington — After his meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy at the White House Friday, President Trump said both Russia and Ukraine should declare victory and "let history decide!"

Zelenskyy told reporters after the meeting that he and Mr. Trump decided not to publicly discuss whether the U.S. will provide long-range weapons, including Tomahawks, citing the "escalation" that could bring in Russia's war on Ukraine. Zelenskyy's comment came mere hours after Mr. Trump expressed openness to trading U.S. Tomahawks for Ukrainian drones.

"We decided that we don't speak about it because nobody wants — the United States doesn't want escalation," Zelenskyy said.

Mr. Trump said in a Truth Social post Friday that his meeting with the Ukrainian leader was "very interesting, and cordial."

He continued, "I told him, as I likewise strongly suggested to President Putin, that it is time to stop the killing, and make a DEAL! Enough blood has been shed, with property lines being defined by War and Guts. They should stop where they are. Let both claim Victory, let History decide!"

Mr. Trump's meeting with Zelenskyy took place a day after the president spoke by phone with Russian President Vladimir Putin and then announced that he and Putin would meet soon in Budapest.

The president expressed some reservations about reducing the number of Tomahawks that the U.S. possesses, though long-range weapons were expected to be a major point of discussion for Mr. Trump and Zelenskyy.

"Tomahawks are a big deal," Mr. Trump told reporters during the meeting with his Cabinet and Zelenskyy. "But one thing I have to say, we want Tomahawks, also. We don't want to be giving away things that we need to protect our country."

"Hopefully, we'll be able to get the war over without thinking about Tomahawks. I think we're fairly close to that," Mr. Trump said.

Advertisement

After Zelenskyy suggested Ukraine might give the U.S. Ukrainian drones in exchange for the Tomahawk missiles, a reporter asked Mr. Trump if it was a trade that interested him.

"We are, yeah," the president responded. "They make a very good drone," he replied.

Zelenskyy and Mr. Trump shook hands when the Ukrainian president arrived at the White House, and a reporter asked the president if he believes he can persuade Putin to end the war. "Yup," Mr. Trump responded.

In their meeting, Mr. Trump was seated across from Zelenskyy, who wore a military-style jacket for the occasion. Mr. Trump complimented him, saying, "I think he looks beautiful in his jacket."

"It's an honor to be with a very strong leader, a man who has been through a lot," Mr. Trump said in the meeting, adding he thinks they're making "great progress" in ending the war.

Advertisement

Zelenskyy congratulated Mr. Trump on the "successful ceasefire" in the Middle East, but he added that he thinks Putin is "not ready" to end the war with Ukraine.

Mr. Trump brought up the possibility that Zelenskyy could join his upcoming meeting with Putin in Budapest, but then added that the meetings "may be separated." A date has not yet been set for Mr. Trump's meeting with the Russian leader.

A reporter asked the president if he's concerned Putin may just be trying to buy more time with the Budapest meeting. "Yeah, I am," Mr. Trump said. "But you know, I've been played all my life by the best of them. And I came out really well. So, it's possible, yeah."

Mr. Trump had previously said the Tomahawks would be a "new step of aggression" in the Russia-Ukraine war. They'd enable Ukraine to strike deep within Russia.

"I might say 'Look: if this war is not going to get settled, I'm going to send the Tomahawks,'" Mr. Trump told reporters earlier this week. "We may not, but we may do it."

The last time the U.S. and Ukrainian presidents met in person was in late September, on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly in New York. Mr. Trump and Zelenskyy spoke twice over the weekend, on Saturday and Sunday, ahead of Mr. Trump's whirlwind Middle East trip to mark the Israel-Hamas peace deal.

Russia has given no indication it wants to end the war. And Ukrainian authorities said there had been another large-scale Russian strike hours before Mr. Trump spoke with Putin on the phone.

"The massive overnight strike — launched hours before the conversation between Putin and President Trump — exposes Moscow's real attitude toward peace," Ukrainian ambassador to the U.S. Olga Stefanishyna said in a statement Thursday. "While discussions about ending the war continue, Russia once again chose missiles over dialogue, turning this attack into a direct blow to ongoing peace efforts led by President Trump."

Mr. Trump in recent months has expressed frustration with Putin over the failure to end the war, though on a separate front, first lady Melania Trump said last week that she has worked with the Russian leader's team to return Ukrainian children to their families. Mr. Trump said the first lady took up that initiative on her own.

U.S. and Russian advisers will be meeting next week in a location that hasn't been disclosed yet ahead of the anticipated Trump-Putin meeting. The president indicated that initial meetings leading up to the meeting with the Russian leader would be led by Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

DPA

Mon, October 20, 2025

US President Donald Trump (L) welcomes Ukrainian President Vladamir Zelensky ahead of their meeting at the White House. Andrew Leyden/ZUMA Press Wire/dpa

US President Donald Trump on Sunday said he thinks Ukraine and Russia should freeze the front line and end the conflict, which would include dividing the eastern Donbas region as a result.

"We think that what they should do is just stop at the lines where they are - the battle lines...go home, stop killing people, and be done," he told reporters aboard the presidential aircraft Air Force One.

When asked whether Trump told Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky that he should cede the Donbas to Russia, Trump said, "No. We never discussed it."

Zelensky met with Trump in Washington on Friday.

The Financial Times, citing unnamed sources, reported that Trump had allegedly urged Zelensky during their meeting on Friday to give up the entire Donbas to end the war.

Such a move would allow Russian President Vladimir Putin to achieve one of his key objectives in the war that Putin started in February 2022.

Stop now, negotiate later

Trump said he thought some 78% of the land had already been "taken by Russia," adding that he wants a halt on the battlefield and the two sides should deal with the details later.

"The rest is very tough to negotiate." Asked what he thought should be done with the Donbas region, Trump said "Let it be cut the way it is. It's cut up right now."

"They can negotiate something later on down the line."

Trump made his comments on his return flight from Florida to Washington.

Before 2014, the industrial region of Donbas had a population of approximately 6.5 million and was the core of Ukraine's heavy industry, rich in coal and iron. However, many mines and factories were already outdated at that time.

Trump pushed Zelenskyy in vulgar 'shouting match' to cede land or be 'destroyed': report

Alexander Willis

October 19, 2025

U.S. President Donald Trump meets with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy during the 80th United Nations General Assembly, in New York City, New York, U.S., September 23, 2025. (REUTERS/Al Drago)

In a private meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on Friday, President Donald Trump urged him to concede a significant amount of territory to Russia or face destruction, a meeting that devolved into a “shouting match” with Trump “cursing all the time,” according to insiders who spoke with the Financial Times in its report Sunday.

“If [Putin] wants it, he will destroy you,” Trump reportedly told Zelenskyy in the closed-door meeting, according to who the Financial Times described as a “European official with knowledge of the meeting,” speaking with the outlet on the condition of anonymity.

According to the insiders who spoke with the Financial Times, Trump “threw Ukraine’s maps of the battlefield” during the tense meeting, urging Zelenskyy to surrender parts of the eastern Donbas region which still remain under Ukrainian control. The concession Trump proposed would be in exchange for Russia ceding small regions near the southern and southeastern Ukrainian cities of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, respectively – the former now under Ukrainian control and the latter under Russian control.

But for some Ukrainian officials, surrendering the Donbas region was a nonstarter.

“To give [the Donbas] to Russia without a fight is unacceptable for Ukrainian society, and [Russian President Vladimir] Putin knows that,” said Oleksandr Merezhko, who chairs the Ukrainian parliament’s foreign affairs committee, speaking with the Financial Times.

An unnamed official told the outlet that Zelenskyy was “very negative” following the meeting, while noting that European leaders were “not optimistic but pragmatic with planning next step

Zelenskyy Says He’s ‘Ready’ To Meet Trump, Putin In Budapest For Peace Talks

President Donald Trump participates in a bilateral meeting with Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City, Tuesday, September 23, 2025. (Official White House Photo by Daniel Torok)

October 20, 2025

By RFE RL

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that he’s “ready” to sit down for peace talks in Budapest as he expressed doubts about Russian President Vladimir Putin’s willingness to end the more than three-year-long war in Ukraine.

“I’m not sure that Putin is ready just [yet] to finish this war,” Zelenskyy said during a pre-taped interview with NBC that aired on October 19. “I think that maybe he wants to come back with aggression.”

The Ukrainian president said that he believes Putin prefers to postpone “real peace negotiations” and is reluctant to meet with him because that would require agreeing to specific positions and potential concessions to end the war.

Zelenskyy then called for added pressure on the Russian leader, saying that Putin is “afraid of sanctions” and secondary sanctions that would squeeze the Russian economy.

The comments come after US President Donald Trump welcomed Zelenskyy to Washington on October 17 to discuss future peace negotiations.

Zelenskyy arrived for his third meeting at the White House this year prepared to discuss a potential arms deal in which Ukraine would supply the US military with drone technologies in return for long-range Tomahawk missiles, but Trump appeared to have cooled to the idea of providing Ukraine with the weapons.

Instead, the US president urged Russia and Ukraine to immediately cease fighting, saying enough blood had been shed, and announced he plans to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin in Budapest in the coming weeks. No date has been set for the summit.

During his interview with NBC, Zelenskyy reiterated his openness to engage in bilateral or trilateral peace talks with the United States and Russia at the table.

He also said that fighting on the battlefield should stop along the current contact line between Russian and Ukrainian forces and a cease-fire should be in place to begin peace talks.

“If we want to stop this war and go to peace negotiations,” Zelenskyy said, “we need to stay where we stay and not give something additional to Putin because he wants it.”

What Comes Next As Negotiators Eye A Summit In Budapest?

The Washington Post reported on October 18 that Putin demanded that Kyiv surrender full control of the Donetsk region, a strategically vital area of eastern Ukraine that is partially occupied by Moscow, as a condition for ending the war during an October 16 phone call with Trump.

Trump has not publicly commented on Putin’s demand and appeared not to endorse it in his public statement after meeting with Zelenskyy at the White House.

“They should stop where they are. Let both claim Victory, let History decide!” Trump wrote on social media on October 17.

The Financial Times, citing people familiar with the matter, on October 19 reported that Trump told Zelenskyy during their White House meeting to accept Russia’s terms for ending the war, including ceding of the Donetsk region.

According to the report, Trump warned Zelenskyy that Putin had threatened to “destroy” Ukraine if it didn’t agree. The White House has not commented on the FT report.

Territorial concessions are expected to be part of any eventual peace deal for Ukraine, but it’s uncertain what Putin might agree to — or what Kyiv could legally offer. Ukraine’s constitution mandates a nationwide referendum to approve any change to the country’s territory, a vote that cannot be held under the martial law imposed since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

A key reason for Zelenskyy’s trip to Washington was the possibility of Ukraine receiving Tomahawk missiles, which are capable of hitting targets at a distance of up to 2,500 kilometers.

Trump appeared to have considered sending Tomahawks to Kyiv for weeks as he grew increasingly frustrated over Putin’s refusal to negotiate an end to the war but then appeared to rule out the possibility — at least for now — after his call with the Russian president.

Zelenskyy claimed that issue of Tomahawk missiles is “very sensitive for the Russians” and that Putin is “afraid that the United States will deliver [them] to Ukraine” because it would allow Kyiv to strike strategic military sites and infrastructure that could derail Russia’s war effort.

“It’s good that President Trump didn’t say ‘no,’ but for today, he didn’t say ‘yes.’” Zelenskyy said.

Ahead of the potential summit in Budapest, US and Russian officials will reportedly be planning more lower-level meetings in advance than had taken place in preparation for the Alaska meeting between Trump and Putin in August.

What Is the Latest From Ukraine?

Ukrainian drones attacked a gas plant on October 19 in Russia’s Orenburg, the largest facility of its kind in the world, and forced it to suspend its intake of gas from nearby Kazakhstan, according to the Central Asian country’s energy ministry.

This marks the first reported strike on the plant, which forms part of the Orenburg gas chemical complex that is operated by the state energy giant Gazprom and handles intake from both the Orenburg oil and gas field and Kazakhstan’s Karachaganak field.

An oil refinery in the Samara-region city of Novokuibyshevsk, nearly 1,000 kilometers from the front line, was also hit by Ukrainian drone strikes, according to Ukraine’s General Staff.

“There has been an increase both in the range and in the accuracy of our long-range sanctions against Russia,” Zelenskyy said in a video address, referring to the recent strikes. “Practically every day or two, Russian oil refineries are being hit. And this contributes to bringing Russia back to reality.”

In recent months, Kyiv has intensified its attacks on Russia’s energy infrastructure, which appear to be causing fuel shortages and price increases inside Russia.

The oil depot in Novokuibyshevsk was also hit last month, with Ukraine’s General Staff reporting substantial damage to its infrastructure at the time.

Meanwhile, Kharkiv, Sumy, and Zaporizhzhya were among the cities hit by guided bombs dropped by Russian jets late on October 18, according to Ukraine’s air defense forces.

Russian drones were also reported over the Chernihiv and Dnipropetrovsk regions. Ten people were injured in Dnipropetrovsk region, local authorities on the morning of October 19, while an energy facility was hit in Chernihiv region, causing a power outage for around 17,000 residents in the north of the country.

Russian forces on October 19 launched a massive strike on a coal mine in the Dnipropetrovsk region, the company and the regional press service of DTEK reported. The exact nature of the attack was not immediately described.

“On the eve of the start of the heating season, the enemy again hit the Ukrainian energy sector. During the attack, 192 employees of the mine were underground,” the mining company said in a statement, later adding that all workers were rescued without serious injuries.

Russia’s relentless nighttime strikes often focus on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, aiming to cut off heating and electricity for civilians as winter approaches in a bid to undermine morale.

RFE/RL journalists report the news in 21 countries where a free press is banned by the government or not fully established.

Ukraine’s credibility crisis: corruption perception still haunts economic recovery

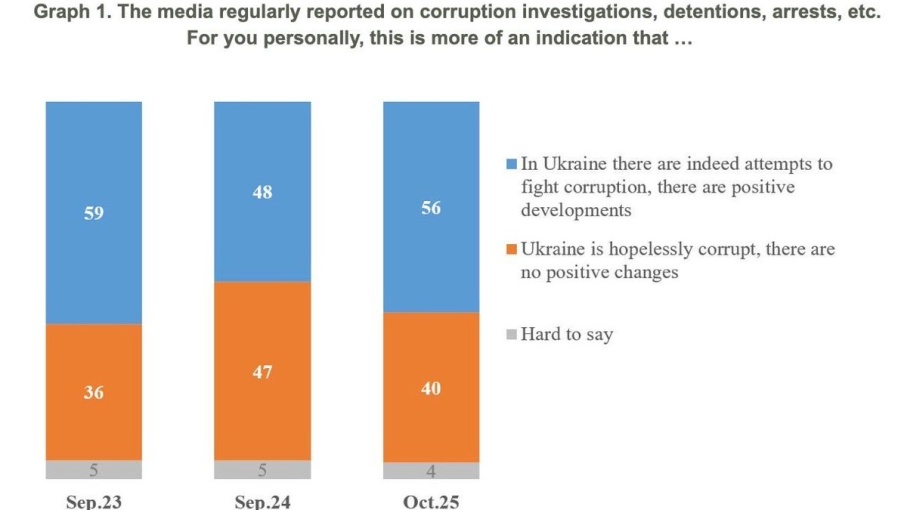

Despite an active reform narrative and growing international engagement, corruption remains the biggest drag on Ukraine’s economic credibility. A recent survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) found that 40% of Ukrainians still believe their country is “hopelessly corrupt,” down only slightly from 47% last year, according to Kyrylo Shevchenko, former Governor of the National Bank of Ukraine.

Shifting in perceptions on corruption are one of the core challenges facing Bankova (Ukraine’s equivalent of the Kremlin) and Ukraine’s reconstruction. On paper reforms have yet to translate into systemic change.

“Every dollar of aid is turned into a political risk,” says Shevchenko. “Until corruption is tackled systemically, the Ukrainian economy will keep bleeding credibility faster than it rebuilds.”

And perceived corruption has undermined US support for Bankova. As part of the emergency $61bn aid package released last April, a line item for some $25mn to cover auditing costs was included to check that US support was not being stolen.

A team of US accountants were sent to Ukraine earlier this year to check the books. And Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy further undermined confidence after he tried to ram through a controversial law that gives unlimited power to the General Prosecutor that civil rights groups say will gut Ukraine’s anti-corruption reforms on July 22. The passage of the law sparked the first anti-government protests since the war with Russia began and Bankova was forced to rapidly back off and return the autonomy of the anti-corruption organs with another law within days.

Nevertheless, over the past year Ukraine has made some progress, says Shevchenko. The High Anti-Corruption Court (ACC)) has issued several high-profile rulings, and digital public procurement tools like ProZorro have improved transparency in some areas. Yet enforcement remains patchy, elite impunity persists, and corruption continues to shape everything from wartime logistics to reconstruction contracts, according to Shevchenko.

The gap between Western expectations and domestic implementation is growing harder to ignore. “Corruption continues to drain investments, block EU integration, and erode donor confidence,” he said. While Ukraine was granted EU candidate status in 2022, Brussels has repeatedly flagged insufficient progress on judicial independence, rule of law, and the de-oligarchizing agenda.

Even among Ukrainians, belief in reform is fragile. The same KIIS survey shows that nearly half the country doubts real change is happening, suggesting that years of unfulfilled promises and high-profile scandals have left a deep institutional scar.

“Public trust remains fragile, with only some improvements,” Shevchenko notes. “Talk of reform is not enough. Delivery is everything.”

The stakes could not be higher. The EU is finalising a multi-year €50bn aid package, while the International Monetary Fund is reviewing a $15.6bn Extended Fund Facility (EFF). Donors increasingly condition their support on measurable anti-corruption benchmarks, including independent audits and personnel reform in the judiciary, customs, and security services.

According to observers, the rationale for Law 21414 that would have gutted the anti-corruption bodies and put corruption investigations under the direct control of the General Prosecutor, a Zelenskiy appointee, was investigations by National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) were focusing on people inside Bankova’s inner circle that the president wanted to head off.

The law was suspended, but according to reports, the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU), which is also under Zelenskiy’s direct control, continued to pressure NABU offices with investigations and inspections.

Meanwhile, investor interest remains cautious. Ukraine is viewed as a high-risk frontier market, despite post-war rebuilding opportunities in energy, logistics, and defence-related industries. But without legal protections and institutional clarity, few are willing to commit long-term capital.

“Donornomics only works when credibility compounds,” Shevchenko said. “Ukraine needs a corruption-proof recovery—not just for the sake of its partners, but for the future of its own citizens.”

Until that happens, Ukraine’s economy will remain suspended between Western lifelines and domestic gridlock. Reform will need to outpace scepticism—for both markets and the millions of Ukrainians still waiting for real change.

Ukraine, European Leaders Anxiously Eye Trump-Putin Summit After White House Meeting – Analysis

Russia's President Vladimir Putin with US President Donald Trump.

October 19, 2025

RFE RL

By Zoriana Stepanenko and Reid Standish

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy came to Washington hoping to get a commitment on new weapons, but instead met an American president newly intent on brokering a peace deal to end the more than three-year war in Ukraine.

Zelenskyy left his October 17 meeting with US President Donald Trump withoutreceiving much-sought Tomahawk cruise missiles. He now finds himself preparing for a new phase of US-led diplomacy as American and Russian officials lay the groundwork for a potential agreement at an upcoming summit between Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Budapest.

“Let both claim Victory, let History decide!” Trump wrote on social media after his meeting with Zelenskyy, saying he had told both leaders this week that “it is time to stop the killing, and make a DEAL!”

After the meeting, which Zelenskyy described as productive, the Ukrainian president spoke by phone with European leaders — including European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, Finland’s president, and the prime ministers of Britain, Italy, Norway, and Poland — and said he was counting on Trump to pressure Putin “to stop this war.”

The European leaders reaffirmed their support for Kyiv on the call and said that they will continue work on developing a peace plan for Ukraine, as well as options to increase pressure on Moscow through sanctions and the use of frozen Russian state assets.

“The most important thing now is to protect as many lives as possible, ensure security for Ukraine, and strengthen us all in Europe. This is precisely what we are working towards,” Zelenskyy later said about the call on his Telegram channel.

But analysts and Ukrainian lawmakers told RFE/RL that the lack of a commitment on Tomahawk missiles, another summit between Putin and Trump, and the US president’s apparent softening rhetoric towards Putin after spending weeks threatening sanctions and potential weapons deliveries has raised anxiety levels in Kyiv.

While Volodymyr Dubovyk, associate professor of international relations at Odesa University, told RFE/RL that Trump’s softening tone towards Ukraine compared to earlier meetings with Zelenskyy this year reflects a “positive dynamic,” others do not share his optimism.

“I am surprised to hear that my colleagues have high hopes for this season of negotiations,” Solomiia Bobrovska, a Ukrainian lawmaker who sits on the parliament’s National Security Committee, told RFE/RL, referring to the White House meeting and a summit slated for the coming weeks in Budapest.

“If we can shift Trump’s complacency for Russia even a millimeter away and closer towards Ukraine, then that is will be good,” she added.

From Tomahawks To A Summit In Hungary

A similar unease is shared by Oleksandr Sushko, the executive director of the Kyiv-based International Renaissance Foundation.

“Trump appears to be only partially on [Ukraine’s] side,” he told RFE/RL. “Therefore, it is very important to remain sober and restrained here.”

In the weeks leading up to his meeting with Zelenskyy, Trump had mused about sending Kyiv Tomahawk missiles as he appeared to sour on Putin over his refusal to negotiate a deal to end the war.

A key reason for Zelenskyy’s hastily organized trip to Washington was the possibility of Ukraine receiving the missiles, which are capable of hitting targets at a distance of up to 2,500 kilometers.

But an October 16 phone call between Putin and Trump, which occurred while the Ukrainian president was in transit to the United States, changed that with a future meeting between the two leaders set for the coming weeks in the Hungarian capital.

At a press conference after his White House meeting, Zelenskyy was asked about the missiles and what he had been told by US officials.

“We want [them] very much… we need them,” he said. “Nobody canceled this dialogue, this topic.”

Later, Trump reiterated that he wants the United States to hold on to its weaponry. “We want Tomahawks also. We don’t want to be giving away things that we need to protect our country,” he said.

Zelenskyy also said he is open to bilateral or trilateral talks to end the war.

“I don’t rule out that [long-range weapons] will be used someday, but [they] will definitely not be used in the coming weeks,” Viktor Shlinchak, chairman of the board of the Institute of World Politics, told RFE/RL.

All Eyes On Budapest

Trump’s decision to organize another high-profile summit with Putin has somewhat changed the calculus for Kyiv, Heorhiy Chizhov, head of the Kyiv-based Center for Promoting Reforms, told RFE/RL.

“[Trump] thinks he can win, that he can get Putin to the negotiating table,” Chizhov said.

Asked by a reporter on October 17 if he thinks Putin is trying to buy time, Trump replied that he has been “played” all his life by “the best of them,” but said he thinks Putin wants to make a deal.

According to Russian foreign-policy advisor Yury Ushakov, Putin had warned Trump that allowing Ukraine to purchase the Tomahawks “won’t change the situation on the battlefield but would cause substantial damage to the relationship between our countries.”

US officials are reportedly planning more lower-level meetings with their Russian counterparts than had taken place ahead of the Alaska meeting between Trump and Putin in August.

The American side will be led by Secretary of State Marco Rubio instead of special envoy Steve Witkoff, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Trump has so far been cautious about ratcheting up pressure on Putin, but his administration also expanded intelligence sharing with Ukraine to help it strike targets inside Russia and imposed steep tariffs on one of Moscow’s top trading partners, India, over its purchases of Russian oil.

In early October, the Trump administration also sanctioned Serbia’s largest oil and gas supplier, which is majority-owned by Russian state energy giant Gazprom.

Russian officials also appear to be preparing their own offerings to present to the US side in talks.

Kirill Dmitriev, the head of Russia’s sovereign wealth fund, revived the idea of building a tunnel under the Bering Sea to connect Russia and the United States though Alaska and suggested that Elon Musk’s Boring Company build it.

Reid Standish is RFE/RL’s China Global Affairs correspondent based in Prague and author of the China In Eurasia briefing. He focuses on Chinese foreign policy in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and has reported extensively about China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Beijing’s internment camps in Xinjiang. Prior to joining RFE/RL, Reid was an editor at Foreign Policy magazine and its Moscow correspondent. He has also written for The Atlantic and The Washington Post.

RFE RL

RFE/RL journalists report the news in 21 countries where a free press is banned by the government or not fully established.

Hungary offers Putin safe passage for Budapest summit despite ICC arrest warrant

Preparations for organising the planned summit between US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin are progressing at full speed, Prime Minister Viktor Orban told state media on October 17, state news agency MTI writes. Despite the International Criminal Court's arrest warrant against Putin, Hungarian authorities have stated the Russian president will face no legal risk during the visit.

Orban told Kossuth Radio that Marc Rubio and his Russian peer will aim to settle any remaining unresolved matters in the coming week, and then the two leaders can meet in Budapest a week later, he said. The prime minister confirmed had held phone talks with President Putin to discuss the upcoming meeting, while Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto discussed details with US Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau and Sergei Lavrov.

The prime minister said there had been "no real alternative" to Budapest as the venue for the meeting, noting that Hungary was "the only pro-peace country in Europe" and that it was Budapest that advocated keeping diplomatic channels open.

He said the upcoming summit was "not about Hungary, but about peace", describing it as a major diplomatic achievement that Budapest had been selected to host such a high-level event.

The EU had already spent €180bn on the war, and ending the conflict could "double or triple" Hungary's economic growth. The temporary inconveniences caused by hosting the summit were therefore "worth it", he said, adding that "nothing is as profitable as peace".

"If they were looking for a secure place in terms of peace and things will be in order technically, they will not be surprised by any political events, so they were looking for a predictable environment, then Budapest seems like a logical choice," he said.

The prime minister said he was told by Trump on October 16, that a meeting of the US secretary of state and the Russian Foreign Minister was on the agenda.

When asked about picking Hungary as the location, Trump said at a joint press conference with Ukraine's leader on October 17, that "Hungary has a leader we like. "We love Viktor Orban, he loves him, I love him," referring to Putin.

The US president said Budapest was chosen as the venue because Hungary is "a safe country, very well run," and "free from many of the problems other countries face," and that Orban would be "a very good host."

When asked why Hungary remains reliant on Russian energy despite US pressure on other countries, Trump said Hungary's dependence stems from its "special situation" as a landlocked country that relies on a single oil pipeline.

Trump's White House aides were not that cordial to US media. When HuffPost asked who suggested Budapest for the venue, given that Russia promised not to invade Ukraine in the 1994 Budapest memorandum, Karoline Leavitt responded, "Your mum did."

By October 19, more details emerged from the Friday meeting between the US President and the Ukrainian leader. The Financial Times reports that Donald Trump has urged Volodymyr Zelensky to accept Russia's conditions and has reportedly pressed Zelensky to hand over the entire eastern Donbas region to Russia. Trump reiterated several arguments similar to those made by Putin in a phone conversation the previous day, financial website Portfolio.hu recalls.

The Financial Times said Putin, during his October 16 with Trump, offered to cede small parts of the southern Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions in exchange for the much larger Donbas territories currently under Ukrainian control. This represents a scaled-back version of Moscow's 2024 demand for Kyiv to surrender all of Donbas as well as Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, a total area of roughly 20,000 sqkm.

In an interview with NBC News' Meet the Press, the Ukrainian leader said he is prepared to attend the planned peace talks in Budapest and called on Donald Trump to adopt a tougher approach towards Russia. The Ukrainian leader described Putin as a "terrorist" but expressed readiness for direct talks, saying, "If we really want just and lasting peace, we need both sides." Zelensky also reaffirmed that Ukraine would not cede additional territory, insisting peace talks must be held "not under missiles, not under drones."

In spite of an International Criminal Court arrest warrant against Russian President Vladimir Putin, Hungary will not detain him during his planned visit, Hungary's chief diplomat said.

Szijjarto stated that the Hungarian government guarantees Putin unhindered entry and exit from Hungary and will ensure the success of his negotiations. He emphasised that no consultation with other parties is required, as Hungary is a sovereign state.

The EU ban on Russian air traffic could complicate and prolong Putin's trip to Budapest. Because security rules require him to travel on the Russian presidential plane, Putin would need special clearance to cross EU or NATO airspace to come to Budapest.

Likely routes could involve detours through Turkey, Bulgaria and Serbia, or through Turkey, Greece and Montenegro, as overflight through Ukraine or Poland is seen as impossible, BBC writes.

Speaking to MK.ru, Russian security expert Alexander Kotz suggested a route crossing the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Serbia, possibly via Bosnia-Herzegovina, as the safest option for Putin.

According to EU officials, member states may individually grant overflight or landing permission to Putin if he chooses not to travel through Ukraine or via a Balkan detour. Politico noted that under EU sanctions law, national authorities can make exceptions to the Russian airspace restrictions if such flights are deemed necessary for humanitarian or compatible purposes.

Local media, citing security experts say Budapest has had experience hosting high-profile events, but the summit poses unprecedented security challenges.

Preparations for the summit are underway in Budapest. The operation involves Hungarian police, counter-terrorism units, armed forces, cyber experts, and the US and Russian security services. Preparatory talks begin this week, and the capital will face road closures and transport disruptions during the summit.

The official venue is yet to be announced, with multiple locations under consideration.

WAIT, WHAT?!

Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko has opened the door to direct dialogue with Kyiv as part of negotiations to end Russia’s war in Ukraine, as he launches a diplomatic drive to break the republic’s isolation and total dependence on Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The head of Belarus' State Security Committee (KGB), Ivan Tertel, told state television on October 19 that his agency is prepared to engage with Ukraine “to find a consensus” and prevent further escalation.

“Our president works as much as possible in order to stabilise the situation in the region,” Tertel said, referring to Lukashenko, the country’s long-serving and internationally ostracised leader. “And we’ve managed to balance the interests of the parties in this extremely complicated situation with a tendency towards escalation.”

“I am convinced that only via quiet and calm negotiations, by looking for a compromise, we will be able to resolve this situation,” Tertel added, pointedly noting that “a lot depends on the Ukrainian side”.

The call for talks comes after Minsk sent letters to various EU member states offering to open a dialogue last week. Belarus is bidding for better relations with the EU after making notable progress in improving ties with the Trump administration, according to diplomatic sources cited by Reuters.

The diplomatic olive branches come after ties with the US have dramatically improved in recent months. US mediation was instrumental in bringing off a number of political prisoner releases. The most high profile are the release of 16 prisoners, including Sergey Tikhanovsky (Siarhei Tsikhanouskiy), the husband of Belarusian opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya (Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya), in June following a US-brokered pardon after envoy Keith Kellogg met with Lukashenko in Minsk. Another 52 prisoners were released in September after more US mediation. However, some 1,300 people remain in jail, according to human rights groups.

Nevertheless Belarus remains a key ally of Moscow and Lukashenko is a frequent visitor. Belarus has also hosted Russian military assets since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 including Russian missiles and nuclear weapons.

Kyiv has not officially responded to the offer.

Lukashenko walks a rhetorical tightrope

Earlier this month, Lukashenko lashed out at Ukraine’s refusal to negotiate with Moscow, warning that “Ukraine may cease to exist as a state” unless President Volodymyr Zelenskiy “sits down, negotiates, and acts urgently”.

At the same time Lukashenko has offered to host a potential bilateral or trilateral meeting between Putin, Zelenskiy and US President Donald Trump – an offer that Bankova has rejected out of hand.

Since the 2020 presidential election — widely condemned by the EU and US as fraudulent — Belarus has faced heavy sanctions and pariah status among democratic nations. The situation worsened after Belarus allowed Russian forces to use its territory to launch part of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

According to Reuters, Belarusian diplomats recently met with European officials. One European diplomat confirmed a meeting with former Belarusian Deputy Foreign Minister Yuri Ambrazevich, who reportedly suggested Belarus could be included in wider talks about European security architecture, Reuters reports.

Washington has taken the lead in the rapprochement, brokering several political prisoners released from Belarusian jails. In return, the Trump administration agreed to lift some sanctions on the Belarusian state airline, Belavia that will allow Minsk to buy US-made plane parts again.

Trump’s envoy, retired General Keith Kellogg, later confirmed that the aim of the renewed dialogue was “to ensure lines of communication” with Putin.

“The goal is not to rehabilitate Lukashenko, but to widen the channels through which we can pressure Moscow,” a US official familiar with the talks said privately, Reuters reports.

Despite these diplomatic stirrings, Belarus remains deeply entwined with Moscow’s strategic ambitions. Last month, Russia and Belarus conducted the joint quadrennial Zapad-2025 military exercises – a show of military strength, involving an estimated 100,000 troops in exercises to simulate a conflict with Nato forces.

“Belarus may be testing the waters to become a ‘neutral’ channel for negotiation—without ever actually changing sides,” one analyst said, reports The Kyiv Independent.

Tertel’s comments on Belarus One come just days after Belarusian diplomats were seen stepping up contact with EU envoys amid renewed speculation over a potential Russia-US summit in Budapest.

The Transparency Doctrine: How Democracies Learned To Pre-Bunk War – Analysis

"Little Green Men" soldiers in Crimea. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

October 20, 2025

By Aritra Banerjee

In 2014, when “little green men” appeared in Crimea, the world was caught off-guard. Russia’s denials, obfuscations, and media manipulation muddied the waters long enough to make annexation a fait accompli. Eight years later, in the winter of 2021-22, the same state prepared for another incursion — but this time, its opponent’s information playbook had changed.

Throughout January and February 2022, Washington and London released an extraordinary series of intelligence assessments detailing Russia’s build-up, likely pretexts, and even fake videos that Moscow intended to stage. The world knew the war was coming before it began. What seemed like a radical breach of intelligence culture — governments revealing secrets rather than guarding them — was a calculated act of strategic communication.

As Jānis Sārts, Director of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence (StratCom COE) in Riga, explained, the decision aimed “to alert the world and to make it more complicated for Russia to stage the pretext for war.” In effect, NATO allies decided to foretell the lie before it could be told.

From Secrecy to Strategic Disclosure

For decades, intelligence orthodoxy treated information as something to protect, not deploy. Secrecy implied control; revelation implied risk. But in the era of hybrid warfare, ambiguity itself became a weapon. Adversaries like Russia learned to operate in the grey zone — manipulating half-truths, manufacturing confusion, and eroding trust faster than democracies could verify facts.

By 2017, after Russian interference in the U.S. and European elections, NATO’s StratCom community had begun to rethink that equation. Sārts recalls testifying before the U.S. Senate that year, urging a new mindset: “In 21st-century information warfare, the traditional approach to intelligence — briefing leaders but keeping information classified — no longer works.”

That intellectual shift drew from the work of Dr Neville Bolt, Founder and Director of the Sympodium Institute for Strategic Communications, following two decades as Director of the King’s Centre for Strategic Communications (KCSC) and Reader in Strategic Communications at King’s College London.

Dr Bolt, who also serves as Editor-in-Chief of Defence Strategic Communications — NATO’s peer-reviewed academic journal — argues that strategic communication is not a collection of messaging tools but a “mindset — a way of understanding the world where politics now takes place inside the information environment.”

The Western intelligence community finally operationalised that theory in early 2022. Controlled transparency replaced quiet briefing. Truth became an instrument of manoeuvre.

Pre-Bunking in Action

Between late 2021 and mid-February 2022, the U.S. and U.K. issued near-daily warnings: Russia would stage atrocities, fabricate videos, or provoke border incidents. Each statement forced the Kremlin to rewrite its script in real time. When the invasion began on 24 February, Moscow’s justification — “genocide in Donbas” — looked hastily improvised and conspicuously hollow.

The pre-bunking strategy achieved three immediate effects:It stripped Russia of surprise. Every possible false flag had been publicised in advance.

It compressed global interpretation time. By the time Russian state television rolled out its storyline, audiences were already inoculated.

It accelerated alliance cohesion. Western capitals coalesced around a single, pre-validated narrative of aggression.

The risks were real. With limited evidence they could reveal, U.S. officials endured hostile questioning at press briefings. Yet that discomfort was a price worth paying. As Sārts observed, “It looked uncomfortable, but it worked.” The Kremlin’s vaunted information dominance failed at the opening whistle.

Information Timing, Audience Trust, Strategic Effect

Strategic communication often fails because it treats words as content rather than manoeuvre. Timing is the first variable: pre-bunking succeeds only when disclosure precedes the adversary’s narrative window. Audience trust is the second: the public must already believe the communicator’s integrity for transparency to carry weight. Strategic effect is the third: the goal is not merely to inform but to alter the adversary’s cost-benefit calculus.

In February 2022 all three aligned. By telling uncomfortable truths early, democracies generated cognitive shock in Moscow, narrative compression among Western audiences, and strategic synchronisation among allies. The manoeuvre turned openness into deterrence.

Russia’s Message Creep

Contrast this clarity with Russia’s performance. As Professor Bolt points out in another context, “mission creep breeds message creep.” The same pathology that undermined Western narratives in Afghanistan—constantly shifting goals—afflicted Russia’s information war. Its justifications shifted from protecting Russian speakers to denazification, then to resisting NATO expansion, then to fighting Western decadence. Each revision diluted credibility.

Worse, the Kremlin’s top-down propaganda machine proved incapable of adaptation. Its secrecy culture, once an advantage, trapped it in its own echo chamber. Deprived of honest feedback, the regime doubled down on delusion. In the language of StratCom, it lost the feedback loop that sustains narrative authority.

Ukraine’s Real-Time Counter-Narrative

If the U.S. and U.K. supplied intelligence, Ukraine supplied authenticity. Within hours of the invasion, President Volodymyr Zelensky recorded a short video outside his office: “We are here.” No polished lighting, no staging — just defiance. It cut through the fog of war faster than any press release could.

Sārts calls this the “humanisation of the war.” Ukrainians turned strategic communication into a whole-of-society effort. Every citizen with a smartphone became a sensor, witness, and messenger. Symbols emerged organically — the Snake Island defiance, the sunflower-seed grandmother, the blue-and-yellow memes that flooded timelines.

While Russia’s state-run television pushed sterile narratives, Ukraine’s lived imagery made its story emotionally incontestable. Each viral clip was a micro-pre-bunking act: reality broadcast before distortion could take root.

Leadership as Narrative Architecture

In Neville Bolt’s typology, strategic communication operates through words, images, and actions — but the action of leadership unites them all. Zelensky’s leadership was both message and medium. By staying in Kyiv, refusing evacuation, and addressing parliaments directly, he aligned policy, posture, and persona into a single story of resistance.

Even his informality — fatigue clothes, smartphone videos — served as semiotics of authenticity. It made Western leaders’ rehearsed statements look sterile. In contrast, Vladimir Putin’s long tables and pre-recorded meetings became symbols of isolation and paranoia. Both men performed strategy through imagery; only one resonated.

Pre-Bunking Beyond Europe

The logic of controlled transparency has wider relevance. Democracies in the Indo-Pacific face similar grey-zone pressures — from territorial incursions and cyber intrusions to information warfare that blurs peace and conflict.

For India, which operates in a complex information battlespace involving China and Pakistan, selective disclosure can serve as an instrument of deterrence. Early, credible publication of satellite data, intelligence summaries, or diplomatic assessments can pre-empt adversarial narratives during border crises or disinformation spikes.

The challenge is cultural as much as procedural. Bureaucracies accustomed to secrecy must learn to calibrate revelation. Public trust, already fragile, must be maintained by accuracy and consistency. Pre-bunking works only when audiences believe both the messenger and the motive.

Japan’s communication around the Fukushima disaster in 2011, for instance, demonstrated the cost of hesitation: delayed transparency eroded public trust for years. Conversely, New Zealand’s proactive crisis communication model — factual, timely, empathetic — shows how openness reinforces authority. The EurAsian takeaway: transparency, managed well, is power.

Toward a Doctrine of Strategic Openness

If democracies are to institutionalise what succeeded in 2022, they need doctrine. A national StratCom framework for “strategic openness” would set:Thresholds for disclosure — when classified information serves deterrence more than secrecy.

Inter-agency coordination — linking intelligence, defence, diplomacy, and media spokespeople.

Temporal sequencing — how early warnings transition into crisis communication without fatigue.

Ethical guardrails — ensuring truth, not propaganda, underpins disclosure.

Such doctrine would turn episodic success into sustained capability. It would also answer critics who fear that openness endangers sources: managed transparency is not recklessness; it is risk management for narrative dominance.

The Information Deterrent

Strategic communication’s power lies not in volume but in velocity and coherence. The 2022 pre-bunking campaign demonstrated that information, timed correctly, can alter the strategic environment before the first shot is fired.

In that sense, pre-bunking is deterrence by narration. It denies the enemy plausible stories, constrains their manoeuvre, and rallies allies faster than conventional diplomacy. It also reclaims moral ground: democracies no longer have to choose between truth and security — the two can reinforce each other.

Neville Bolt reminds us that every action, even inaction, communicates. By choosing to speak early, democracies finally acted strategically within the information environment rather than outside it.

The Age of Strategic Truth

The Cold War prized secrecy as power; the information age prizes credibility. In a battlespace where deception is constant and attention is scarce, truth — timely, contextual, and deliberate — becomes an instrument of statecraft.

For NATO in 2022, that truth denied Russia its narrative initiative. For democracies elsewhere, it offers a template: communicate first, communicate honestly, and communicate with purpose.

Transparency will not end wars, but it can shape how they begin — and, sometimes, prevent them from starting at all.

Aritra Banerjee is a Contributing Editor, South Asia at Eurasia Review with a focus on Defence, Strategic Affairs, and Indo-Pacific geopolitics. He is also the co-author of The Indian Navy @75: Reminiscing the Voyage. Having spent his formative years in the United States before returning to India, he brings a global perspective combined with on-the-ground insight to his reporting. He holds a Master's in International Relations, Security & Strategy from O.P. Jindal Global University, a Bachelor's in Mass Media from the University of Mumbai, and Professional Education in Strategic Communications from King's College London (King's Institute for Applied Security Studies).