The future of the Left in India will be decided by the ability of the movement to rebuild and deepen its links with the working people.

MA Baby

Updated on: 12 December 2025

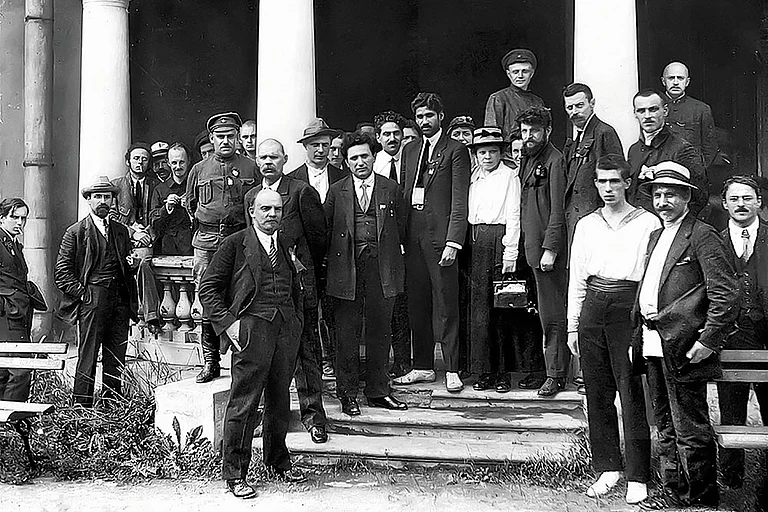

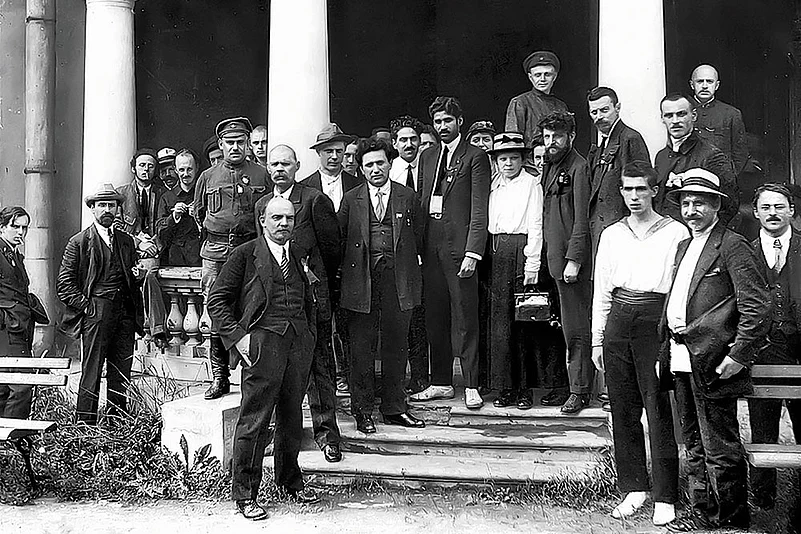

A Historic Gathering: Delegates to the second congress of the Comintern at the Uritsky Palace in Petrograd, including M.N. Roy, Vladimir Lenin, Maxim Gorky and Nikolai Bukharin

Summary of this article

The Left in India has endured for a century because it is rooted in the struggles, dignity and aspirations of workers and peasants.

Left ideas in India were not foreign imports but emerged organically from indigenous egalitarian traditions and early radical thought.

Communists played a decisive role in the freedom movement through organised mass struggles, trade unions, peasant uprisings and cultural platforms.

A hundred years is long enough for political currents to appear and disappear. Parties have risen on slogans and vanished in silence. What has endured in India, despite repression, distortions and political headwinds, is the Left movement. It has endured because it has always belonged to the working people of this country; to their labour, their dignity, and their dreams of a society free from exploitation. From the earliest murmurings of radical thought during anti-colonial resistance to the mass struggles of peasants and workers, from the severe blows of state repression to the experience of forming governments that delivered transformative reforms, the Left has left an indelible mark on modern India. The history of the Left is not parallel to the history of the nation, but it is rather interwoven with it.

The popular misconception that Left ideas were imported from abroad collapses the moment we revisit our own history with honesty. For example, in 1836, even before Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels joined the ‘League of the Just’, Vaikunda Swamikal, a social reformer who lived near the present day Marthandam (part of the erstwhile Travancore) started a utopian socialist movement called ‘Samathwa Samajam’. This is just one example. In fact, an investigation into the history of most societies and civilisations will reveal many examples of historical, mythological or intertwined narratives of a just and egalitarian society.

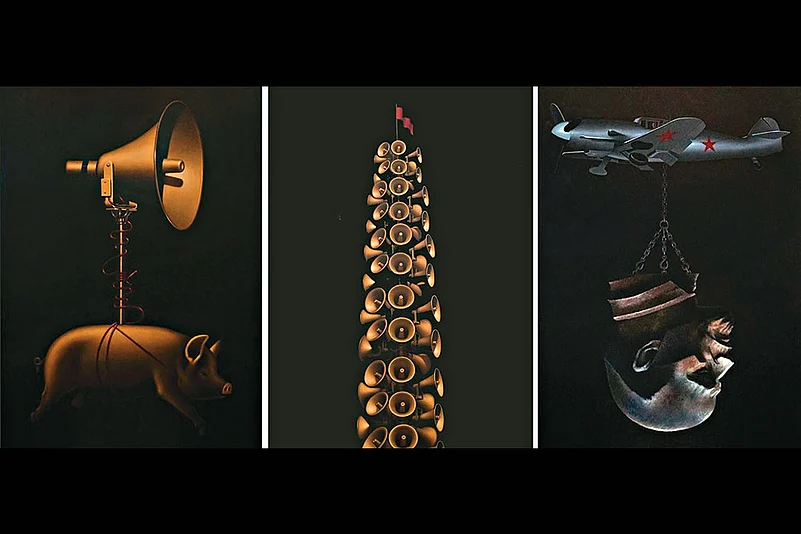

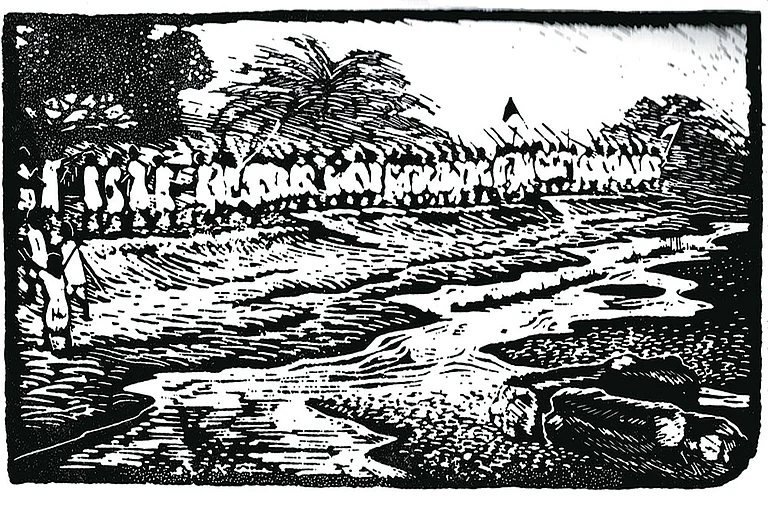

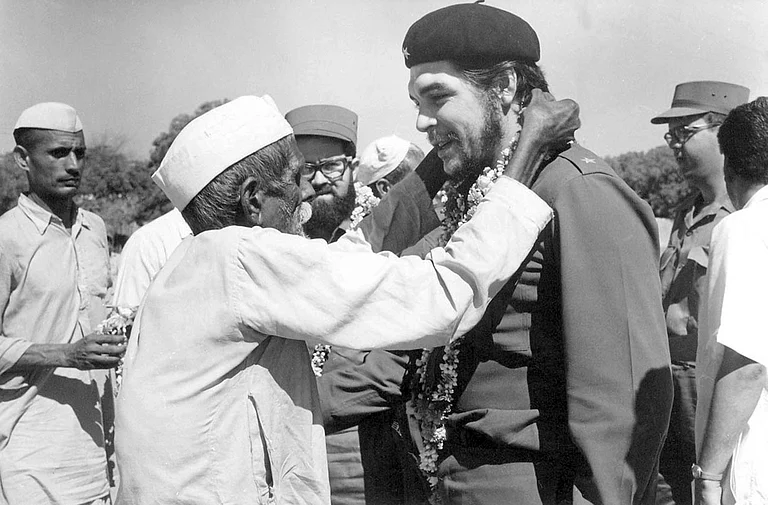

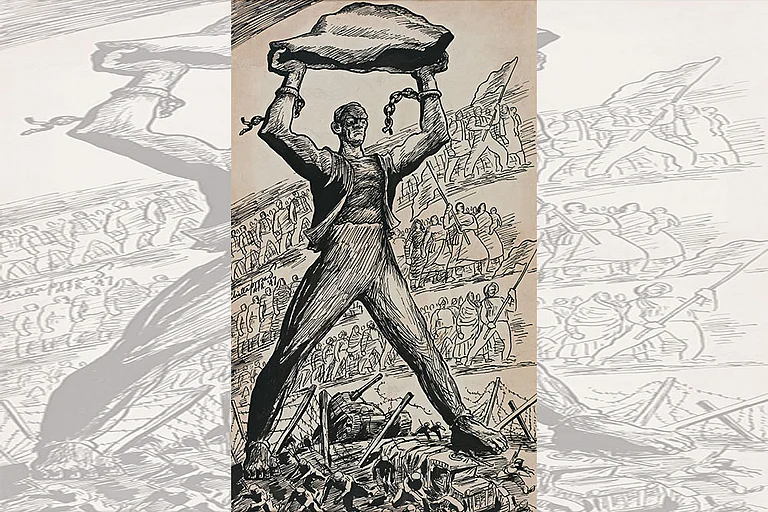

Images Against Darkness: 100 Years Of The Indian Communist Movement And The Culture Of Rebellion, In Photos

The 1905 Russian Revolution electrified the world, but India already had its own revolutionary impulses. The Anushilan Samiti in Bengal and the Ghadar Party in North America reflected an uncompromising resistance to colonial rule and a belief that freedom cannot be begged, it has to be seized. The Ghadarites, many of whom later became communists, carried the message that national liberation was inseparable from social liberation.

The October Revolution of 1917 provided inspiration, but not instruction. India’s young radicals were searching for tools to interpret the exploitation they experienced and witnessed in mills, plantations and villages. This search culminated in the formation of the Communist Party of India at Tashkent in 1920—five years before the party was organised publicly in Kanpur in 1925. The first Secretary of the Party, Mohammad Shafiq, symbolised a simple truth that the Left in India arose not from seminar rooms or drawing rooms, but from intense anti-colonial, anti-imperialist struggle.

Long before the Congress adopted the slogan of Poorna Swaraj in 1929, Hasrat Mohani, a communist, put forward the demand in 1921 at the Ahmedabad session of the AICC along with Swami Kumaranand, a peasant leader. The formation of the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC) in 1920, and later organisations such as the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, the All India Kisan Sabha, the All India Students’ Federation and the Progressive Writers’ Association, turned radical thought into organised mass movements. Workers, peasants, women, students, youth, cultural activists and writers, all found in the Left a political home that combined the struggle for independence with the struggle for social transformation.

One of the final nails on the coffin of the morale of British rule in India was delivered by the sailors of the Royal Indian Navy uprising in 1946. It resulted in an insurrection by over 10,000 sailors and received massive support from the civilians and even police forces of the country. This mutiny was a loud message to the British that Indian soldiers will no longer aid or become a tool for the exploitation of their own people. It must not be forgotten that the sailors were proudly flying the Red Flag of the Communist Party on their ships (along with those of the Congress and the Muslim League flags) during the rebellion.

Crores On Strike: Bharat Bandh Disrupts Services Across India

Mass Struggles That Redefined India

What distinguishes the Left’s contribution to the freedom movement is not rhetoric but sacrifice. The communists led united struggles of workers and peasants that shook the pillars of colonial rule and feudal power. The Tebhaga movement in Bengal demanded two-thirds of the produce for the tiller. The Telangana struggle was carried forward by countless ordinary villagers, including women leaders like Mallu Swarajyam, and it confronted the nexus of feudal lords and the Nizam’s private militia. In the princely state of Travancore, the Punnapra-Vayalar uprising challenged autocratic rule. Each struggle was met with brutal repression. Yet each of them created a new political consciousness: that the land belongs to those who cultivate it, wealth belongs to those who produce it, and democracy means nothing without dignity.

Across the country, peasant movements asserted themselves in different contexts with shared aspirations. In Malabar, the struggles against Jenmi landlordism built the foundation of the Kisan Sabha. In Thane district, Adivasi struggles after 1947 challenged debt bondage and land dispossession under the leadership of the Sabha. P. Sundarayya, who would later lead the Communist Party of India (Marxist) as its General Secretary, dedicated his life organising poor peasants and farm workers, and towards the study of agrarian relations throughout undivided Andhra. In Tamil Nadu, G. Veeraiyan and others organised agricultural labourers against caste-linked exploitation and violence. The agrarian movement in Thanjavur was built by the CPI(M) and its mass/class organisations. This movement was intricately linked with the anti-caste struggle and over time, it gained so much strength that even the very idea of an agricultural union existing irked the landlords so much that they organised a gruesome massacre in the Keezhvenmani village, killing 44 Dalits, the majority of whom were women and children.

Kunwar Mohammad Ashraf (1903-1962): The Gandhi-ite Communist

Similarly, it was the CPI(M) and progressive class organisations that led a relentless struggle to get justice for the survivors of Vachathi state violence. These movements struck at the most deep-rooted structures of Indian society including but not limited to caste hierarchy, patriarchy and the culture of unpaid, invisible, unrecognised labour. In this sense, the Left did not wait for independence to begin fighting for social transformation. The battle for social equality was already underway in the fields and factories much before 1947. The Draft Platform for Action, 1930 was the first attempt towards preparing a programme for the party. This document recognised the ruthless abolition of the caste system along with agrarian revolution and overthrow of British rule as a necessity to achieve the complete social, economic, cultural and legal emancipation of all workers.

The years immediately after independence were marked by severe repression of the communists. The Telangana struggle was crushed with horrendous state repression. Leaders and cadres were jailed, forced to go underground, or killed in fake encounters. A distorted narrative was created to paint the Left as a threat to the nation precisely because the Left was demanding that land and power be returned to the people. Yet the repression did not erode the movement. Instead, it solidified the understanding that political democracy without economic democracy is hollow.

The turning point in parliamentary recognition came in 1957 when Kerala elected the first Communist government through the ballot. Land reforms, education reforms and democratic decentralisation fundamentally altered the social landscape of the state. The 1957 experiment proved that the Communists can govern, not just agitate; and govern in ways that expand people’s rights, not restrict them.

In later decades, Left governments deepened that legacy. In West Bengal, Operation Barga secured tenancy rights for millions of sharecroppers and laid the groundwork for rural poverty reduction. The panchayat system that empowered local democracy emerged in West Bengal and Kerala long before it was recognised in the Constitution in 1992. In Tripura, land redistribution ensured that two-thirds of land went to a tribal population that formed one-third of the state. These should be seen as parts of a coherent model of development in which human welfare is not an afterthought, but the starting point.

These experiences speak volumes about why Kerala continues to repose confidence in the Left, electing it twice in succession, something that has been unprecedented in the state’s political history. When governments deliver social justice in real terms, people do not forget.

Whenever India has been threatened by authoritarianism, the Left has taken an unmistakable stand. During the Emergency, when many parties compromised or justified excesses, we who opposed it paid a heavy price, but still refused to surrender constitutional and democratic rights. In the decades since, the Left has been the most consistent force against communal polarisation. It recognised much earlier than others that communal politics is inseparable from economic inequality, a divided society is easier to exploit.

What's Left Of The Left: The Thin Red Line In J&K

The crises India faces are the outcome of policies that prioritise private profit over public good and division over unity. A different future is possible—one based on secularism, equality, dignity of labour and democratic rights.

The CPI(M) warned in its 23rd Party Congress about the rise of the communal-corporate nexus which is an alliance of reactionary social forces and big capital. Today, as public assets are being handed over to private monopolies and dissent is being increasingly criminalised, that warning reads not like a precise description of current reality.

Whenever labour rights, public sector enterprises or natural resources have been threatened, the working class with the Left at the forefront has fought back , whether it is to prevent the sale of strategic Public Sector Units or to resist anti-worker labour codes. The one-year-long farmers’ movement on the borders of Delhi, which forced the repeal of three farm laws, saw active, consistent and disciplined participation from peasant organisations like the All India Kisan Sabha and other democratic and Left forces. The Kisan Long March in Maharashtra, where thousands of poor peasants walked peacefully with red flags, became a symbol of how democratic mobilisation can achieve what electoral arithmetic cannot.

Why the Left Matters Even More Today

There is a popular trend to judge political relevance solely by election results. But the Left’s history in India shows that the yardstick for us has always been larger: the strength of our links with working people, our ability to organise struggles, and our capacity to offer an alternative vision. Even in a period when the Left’s electoral strength is seeing unprecedented setbacks, its ideological and organisational presence continues to shape resistance movements across the country.

The recent achievements of the Extreme Poverty Eradication Programme launched in Kerala show that it was a policy initiative grounded in the conviction that no human being should live without dignity. It does not mean that Kerala is free of poverty, but the achievements of this programme are a significant step in that direction.

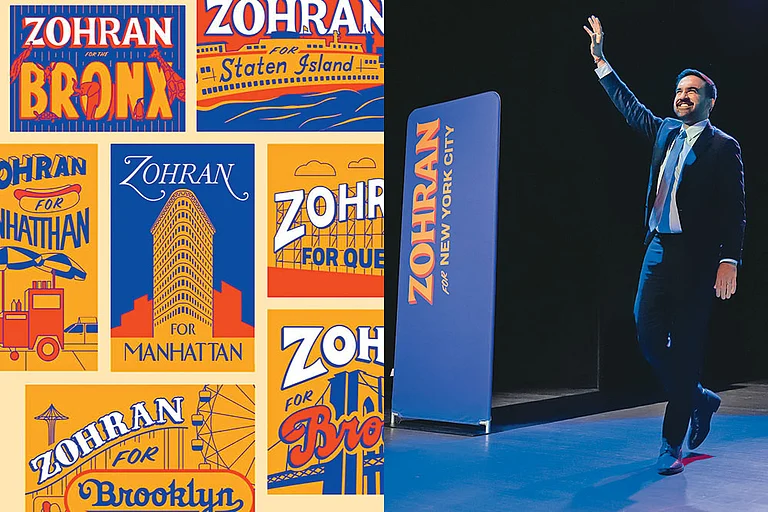

It is this orientation that explains the renewed interest among young people in progressive politics worldwide. Against the rise of the far-Right forces, the youth are also marching behind the new faces of the Left and progressive forces in their countries to challenge inequality, corporate power and racism. The examples of Anura Kumara Dissanayake, Catherine Conolly, Zohran Mamdani, and countless other unnamed organisers and forces, speak volumes about this renewed interest. India is not an exception to this global churn.

Dhoom Macha Le: How Zohran Mamdani’s NYC Mayoral Victory Challenges Authoritarian Trends

The Next 100 Years

The Left movement in India has completed more than a century, but its task is far from finished. It has fought for generations of workers, peasants, women, students and marginalised communities; not for the sake of abstract ideals, but for concrete improvements in their lives and in the society as a whole. The future of the Left will be decided by the ability of the movement to rebuild and deepen its living links with the working people and other toiling masses.

Applying the scientific understanding of Marxism-Leninism in the concrete conditions of India is pertinent to achieve the above. As Young Comrade Lenin once mentioned, “We do not regard Marx’s theory as something completed and inviolable; on the contrary, we are convinced that it has only laid the foundation stone of the science which socialists must develop in all directions if they wish to keep pace with life. We think that an independent elaboration of Marx’s theory is especially essential for Russian socialists; for this theory provides only general guiding principles, which, in particular, are applied in England differently than in France, in France differently than in Germany, and in Germany differently than in Russia. We shall therefore gladly afford space in our paper for articles on theoretical questions and we invite all comrades openly to discuss controversial points.” (Collected Works of Lenin, Vol. IV, pp. 211-212).

The crises India faces are the outcome of policies that prioritise private profit over public good and division over unity. A different future is possible—one based on secularism, equality, dignity of labour and democratic rights. For that to become a reality, the Left is not just relevant but indispensable. The struggles of the past 100-plus years have immensely contributed towards shaping the democratic foundations of India. The next 100 years must complete the unfinished task of revolutionary social transformation.

(Views expressed are personal)

https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/

M.A. Baby is General Secretary, Communist Party of India (Marxist)

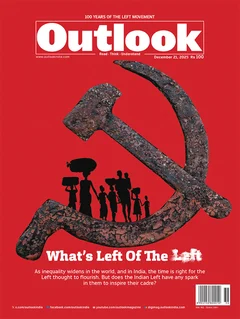

This article appeared as 'We Shall Overcome' in Outlook’s December 21, 2025, issue as 'What's Left of the Left' which explores the challenging crossroads the Left finds itself at and how they need to adapt. And perhaps it will do so.