Venezuela Is Not About Drugs Or Migration: It Is Trump’s ‘Ukraine Moment’ – OpEd

By M.K. Bhadrakumar

The Pentagon has deployed special operations aircraft, troops and equipment to the Caribbean region near Venezuela, The Wall Street Journal and other media reported on December 23. A significant force amassed in Puerto Rico, which has traditionally served as critical hub for refuelling, resupply and surveillance operations.

The 27th Special Operations Wing and the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment deployed in the Caribbean specialise in supporting high-risk infiltration and extraction missions and providing close air support while the Army Rangers are tasked with seizing airfields and protecting special operations units such as Delta Force during precision kill or capture missions.

A satellite photo released this week by the Chinese private aerospace intelligence firm Mizar Vision showed the US Air Force F-35 fleet. The roughly 20 combat jets include a mix of F-35As and US Marine Corps F-35Bs. The deployments suggest forces are being pre-positioned for potential action.

The Trump administration is disregarding the vehemence of world opinion against any violation of Venezuela’s sovereignty, which was truly reflected in the UN Security Council meeting last week to discuss the increased US military presence in the Caribbean Sea and the enforcement of a de facto maritime blockade of Venezuela.

The Trump administration has read the tea leaves that neither Russia nor China will offer Venezuela anything beyond rhetoric to counter any US aggression. The Russian foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova at a press briefing on Thursday sought to show restraint to “prevent the events from sliding towards a destructive scenario,” while voicing support for Caracas.

As for China, despite being South America’s top trading partner and although a regime change in Caracas would certainly hurt China’s vital interests, Beijing is wary of falling into a geopolitical trap.

Both Moscow and Beijing keep the larger context of US global power projection in view. For Russia, the US role in the coming year or two becomes very crucial for reaching a durable settlement in Ukraine. As for China, the matrix is more complicated.

In December, Beijing issued yet another Policy Paper on Latin America and the Carribean, third in a series, projecting an affirmative agenda for an institutionalised, expanded, and elevated relationship with LAC countries, reflecting China’s growing engagement with the Western Hemisphere and its increasingly comprehensive approach affirming China’s intent to continue building an alternative world order. This needs explaining.

The recent National Security Strategy document issued by the White House does not designate China as the greatest threat to the US, but it nonetheless states that the US government will maintain a military capable of deterring Chinese ambitions on Taiwan by military means. Put differently, it sent mixed signals to China.

On the one hand, the US appears to downgrade competition with China but on the other hand, the Trump administration has not made any significant steps to indicate disengagement in Asia.

Again, on the one hand, there is a colossal recklessness in Trump’s China policy by imposing tariffs on China which has a powerful economy that is capable of harsh retaliation; he has also approved a huge arms sale worth around $11 billion to Taiwan, which includes advanced rocket launchers, self-propelled howitzers and a variety of missiles — a deal that, according to Taiwan’s defence ministry, helps the island in “rapidly building robust deterrence capabilities”.

On the other hand, there is also a stupefying obsequiousness on the part of President Trump, as the bragging of a ‘G2’, exports of advanced chips to China and a permissiveness to allow Tik-Tok to stay open on favourable terms, etc. would signify.

Beijing fears that Washington might be trying to lure it into a false sense of security with its rhetoric and an ostensible geopolitical shift, so it remains cautious.

However, Beijing cannot but factor in the ‘big picture’ as well, which is that Trump is pushing the Americas toward a zero-sum geo-economic order in which the US expects the world to recognise what is being tested here — a blatantly coercive attempt to reorder the region’s resources and financial alignment.

The region’s heavyweights – Brazil and Mexico – stand in open opposition. President Lula da Silva of Brazil warned that an armed intervention would be a “humanitarian catastrophe” and a “dangerous precedent for the world.” Similarly, Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum has offered to mediate, seeking to prevent a return to the era of “gunboat diplomacy.”

This tension threatens to transform the South American continent into a theatre of the New Cold War. Specifically, Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves, and it has utilised them to build a financial fortress in partnership with Beijing. Under the “Loans-for-Oil” model, China injected over $60 billion into Venezuela while the latter paid this debt not in dollars, but in physical barrels of crude.

Through a naval blockade, the US is attempting to dismantle this deal and the non-dollar payment system built around it. It is another story that Washington may also be trying to pressure global prices and squeeze petro-rivals like Russia and Iran.

What is often overlooked is that the US’ current conflict with Venezuela — like Ukraine or Taiwan problems — did not come out of nowhere. To understand the current conflict, we need to go beyond the geopolitics of oil or libertarian political philosophy or drug trafficking.

Things began changing when an anti-American shift began to be noticed in Caracas during Barack Obama’s presidency when most Republicans with a strong political base among Venezuelan migrants and their descendants in Florida — an important political constituency for Trump, by the way — began sensing that Venezuela was on a path to become a strongly anti-American country and a centre of influence for China, among others, in the region.

Nicolas Maduro’s rise to power only reinforced this belief. Suffice to say, neither drug trafficking nor migration can explain the current deterioration in US’ attitude. Only 10-20% of illegal substances smuggled into the US actually come from Venezuela; main migration routes do not even run through Venezuela.

The threat perception is primarily about Maduro’s anti-American stance, as well as his growing cooperation with Iran, Russia, and China. Things have come to a point that the only option left to Washington is to use military force — somewhat like the Kremlin’s 22nd February moment in 2022.

What emboldens the Trump administration is a clear shift in the Western Hemisphere, a continent that had been painted in red in political maps for much of the past two decades. Left-wing forces have not won a single presidential election in Latin America this year. Conservative ideas and policy priorities are gaining ground. Trump has encouraged this trend and in turn feels elated that one after another, those who admire, flatter and even emulate him are being elected.

Another factor is the collapse of Venezuela. The paradox is that traditional definitions of left and right are becoming outdated. If Venezuela is far from socialism, El Salvador is far from pure capitalism. In both cases, the state is operating under a form of kleptocratic, rent-seeking authoritarianism.

That said, while the overthrow of Maduro government is Trump’s stated goal, he is also apprehensive — and, rightly so — that a military confrontation may spiral out of control and that failure may stick to him just as the withdrawal from Afghanistan stuck to Joe Biden. Trump’s best hope was that Maduro would simply roll over.

But Maduro isn’t obliging. And Venezuela is 2.75 times bigger than Vietnam, and more than half of its landmass is covered by forests. Suffice to say, the Kremlin’s advice was empathetic when it made an extraordinary personal appeal to Trump:

“Russia expects the President of the United States Donald Trump to demonstrate his signature sense of pragmatism and reason for finding mutually acceptable solutions in keeping with the international law and norms.”

But then, geopolitics is hard ball and at times it becomes necessary to unleash the dogs of war. Which was what the Kremlin did in Ukraine, after all.

M.K. Bhadrakumar

M.K. Bhadrakumar is a former Indian diplomat.

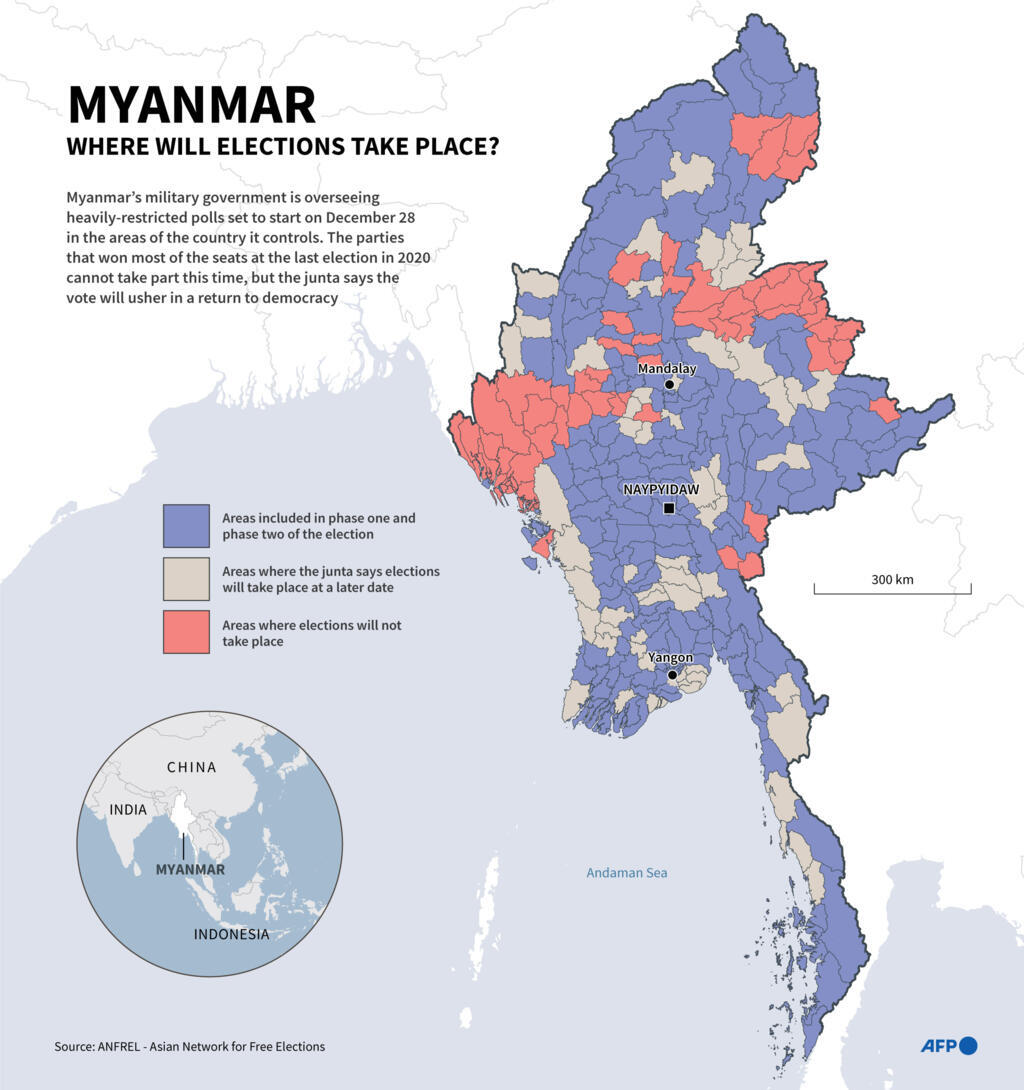

Myanmar: where will elections take place © Nicholas SHEARMAN / AFP

Myanmar: where will elections take place © Nicholas SHEARMAN / AFP