Myanmar’s generals have finally produced the ballot box they have been promising since their 2021 coup. After five years of civil war, mass displacement of entire towns and villages and systematic repression across the country, the junta has staged the first part of what it calls a return to democratic rule.

However, as was reported by the Hindustan Times across the 1,640km border with India - the world’s largest democracy - what appears to be unfolding on election day, Sunday December 28, looks less like an election than a carefully managed performance; one designed to legitimise continued military control while excluding any genuine or effective political competition.

It is a play being staged without many of the actors though, as across junta-held parts of the country, polling stations opened to sparse crowds. In some locations, officials and journalists have reportedly outnumbered voters, reports say. This is a striking contrast to the long queues seen in the last nationwide election in 2020. That was a vote the military annulled before overthrowing the elected government and arresting its leaders the following year.

Under cover of COVID and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the generals have spent the intervening years insisting that a new election would restore stability. What is unfolding on the ground, however, bears little resemblance to that narrative.

The sham in action

As is, Myanmar, a nation of around 50mn, remains fractured by conflict, with large swathes of territory outside the military’s control. Voting is not taking place in rebel-held areas, in effect disenfranchising tens of millions of citizens. Even in cities such as Yangon and Mandalay, where polling stations are open, the atmosphere was largely subdued and tightly policed, the Hindustan Times says.

Added to this, the most popular political force in the country is absent altogether. Aung San Suu Kyi, the former civilian leader and enduring symbol of Myanmar’s democratic movement, remains behind bars and ageing. Now 80-years-old and from time to time reported as being in ill-health, her party, which won a landslide victory in 2020, has been dissolved and barred from contesting the vote. In its place, a field of military-aligned ‘parties’ and approved candidates are competing in a process widely criticised as being rigged from the outset.

As a result, international reaction has been scathing. Human rights groups, Western governments and the United Nations have all dismissed the election as a sham. Think Tank at the European Parliament ran a piece earlier in the month to this end, titled in part “Myanmar: Towards a 'sham' election”.

Efforts to shame the junta’s sweeping restrictions on free speech, assembly and the press, in addition to the ongoing imprisonment of thousands of political opponents is well known.

To this end, the only real beneficiary of the process is the Union Solidarity and Development Party, a pro-military vehicle widely seen as a civilian façade for continued martial rule. Victory for the party will - not would - allow the generals to claim constitutional legitimacy without surrendering real power, thus for Myanmar’s military leadership, the election is not a risk but an insurance policy.

Continued trade with regional partners

On the ground in Myanmar, the junta has long argued that restoring order must come before political freedoms. Yet, as its regional neighbours and the wider world know, it was the coup itself that plunged the country into chaos. Many leaders in the region though opt to turn a blind eye and have to some extent chosen to ignore the internal crisis and oppression of the populace in order to maintain business and trade ties.

These include China, a long time partner pushing the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor under the Belt and Road Initiative and Thailand for whom cross-border commerce includes agricultural products and consumer goods. India too, as well as Singapore and to a lesser extent Malaysia and Indonesia continue to trade with the junta. This is despite the fact that within Myanmar’s borders, air strikes on civilian areas and village burnings coupled to mass arrests continue and have become routine. More than 1mn people have been displaced and humanitarian needs continue to rise. This was only exacerbated by the magnitude 7.7, March 28 earthquake in the region which killed over 3,600.

In this context, the ‘election’ looks less like a step towards any form of effective stability and peace and more like an attempt to rewrite the historical and political narrative - with the tacit help of trade partners across South and Southeast Asia.

By pointing to ballot boxes and polling stations, the generals hope to persuade the wider world to accept the status-quo as it is recognised by China, Thailand India et al, albeit without looking too closely.

For many living in Myanmar, with nowhere else to go, however, staying away from the polls is the only form of protest still open to them.

How Myanmar's junta-run vote works, and why it might not

Yangon (Myanmar) (AFP) – Myanmar's junta presides over elections starting on Sunday, advertising the vote as a return to democratic normality five years after it mounted a coup that triggered civil war.

Issued on: 27/12/2025 - RFI

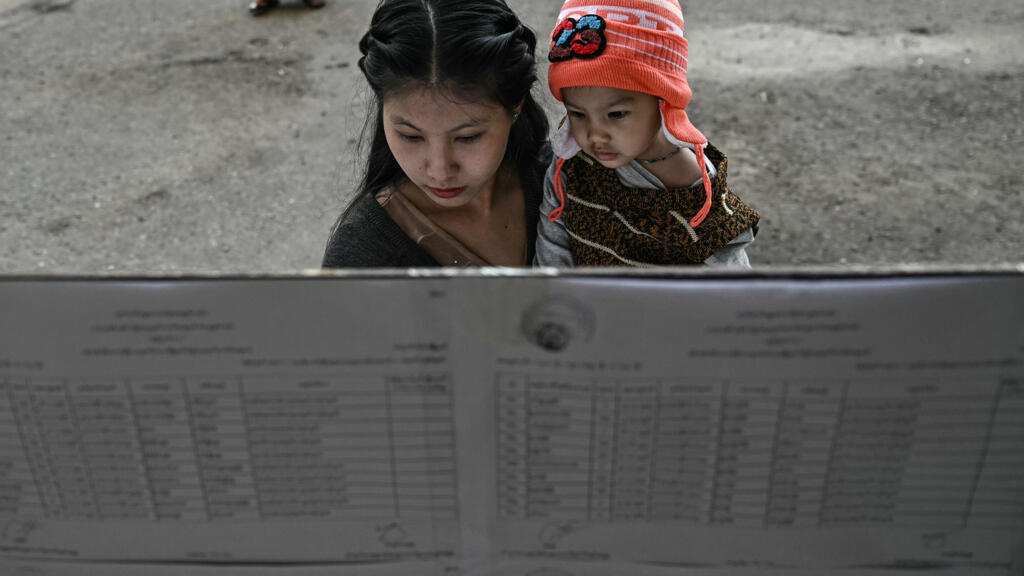

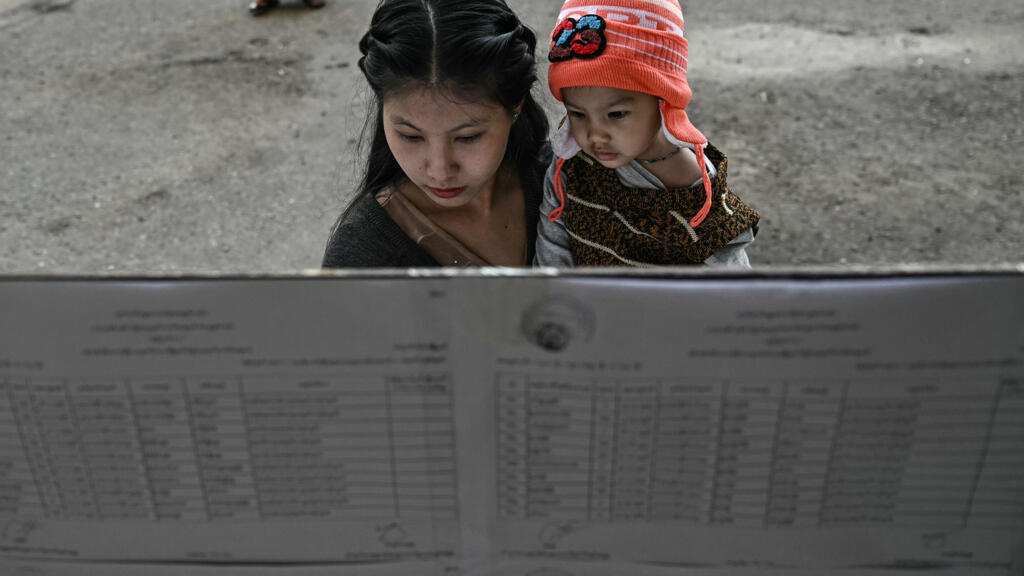

Myanmar's general elections have been widely slated as a charade to rebrand military rule © Lillian SUWANRUMPHA / AFP/File

The vote has been widely slated as a charade to rebrand the rule of the military, which voided the results of the last elections in 2020, alleging massive voter fraud.

Here are some key questions surrounding the heavily restricted polls:

- Who is running? -

The pro-military Union Solidarity and Development Party is by far the biggest participant, providing more than a fifth of all candidates, according to the Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL).

Former democratic leader Aung San Suu Kyi and her massively popular National League for Democracy party, which won a landslide in the last vote, are not taking part.

After the 2021 coup, Suu Kyi was jailed on charges rights groups say were politically motivated.

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners advocacy group, some 22,000 political prisoners are languishing in junta jails.

The National League for Democracy and most of the parties that took part in the 2020 vote have been dissolved. ANFREL says organisations that won 90 percent of seats then will not be on Sunday's ballot.

Polling is taking place in three phases spread over a month, using new electronic voting machines which do not allow write-in candidates or spoiled ballots.

Who can and cannot vote?

Myanmar's civil war has seen the military lose swathes of the country to rebel forces -- a mix of pro-democracy guerillas and ethnic minority armies which have long resisted central rule -- and the vote will not take place in the areas they control.

A military-run census last year admitted it could not collect data from an estimated 19 million of the country's 50 million-odd inhabitants, citing "security constraints".

Amid the conflict, authorities have cancelled voting in 65 of the 330 elected seats of the lower house -- nearly one in five of the total.

More than one million stateless Rohingya refugees, who fled a military crackdown beginning in 2017 and now live in exile in Bangladesh, will also have no say.

How is a winner decided?

Seats in parliament will be allocated under a combined first-past-the-post and proportional representation system which ANFREL says heavily favours larger parties.

The criteria to register as a nationwide party able to contest seats in multiple areas have been tightened, according to the Asian election watchdog, and only six of the 57 parties standing have qualified.

Results are expected in late January.

Regardless of the outcome of the vote, a military-drafted constitution dictates a quarter of parliamentary seats be reserved for the armed forces.

The lower house, upper house, and military members each elect a vice president from among their ranks, and the combined parliament votes on which of the three will be elevated to president.

What happened in the run-up?

Myanmar's military-drafted constitution dictates a quarter of parliamentary seats be reserved for the armed forces © NHAC NGUYEN / AFP

ANFREL says the Union Election Commission overseeing the vote is an organ of the Myanmar military, rather than an independent body.

The head of the commission, Than Soe, was installed after Suu Kyi's government was toppled and is subject to an EU travel ban and sanctions for "undermining democracy" in Myanmar.

Social media sites including Facebook, Instagram and X have all been blocked since the coup, curtailing the spread of information.

The junta has introduced stark legislation punishing public protest or criticism of the poll with up to a decade behind bars, pursuing more than 200 people for prosecution under the new law.

Cases have been brought over private Facebook messages, flash mob protests scattering anti-election leaflets, and vandalism of candidate placards.

Myanmar has invited international monitors to witness the poll, but few countries have answered.

On Friday, state media reported a monitoring delegation had arrived from Belarus -- a country that has been ruled since 1994 by strongman President Alexander Lukashenko, who put down pro-democracy protests six years ago.

© 2025 AFP

Myanmar junta stages election after five years of civil war

Yangon (Myanmar) (AFP) – Voters trickled to Myanmar's heavily restricted polls on Sunday, with the ruling junta touting the exercise as a return to democracy five years after it ousted the last elected government and triggered a civil war.

Issued on: 27/12/2025 - RFI

The pro-military Union Solidarity and Development Party is widely expected to emerge as the largest bloc © Lillian SUWANRUMPHA / AFP

Former civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi remains jailed, while her hugely popular party has been dissolved and was not taking part.

Campaigners, Western diplomats and the United Nations' rights chief have all condemned the phased month-long vote, citing a ballot stacked with military allies and a stark crackdown on dissent.

The pro-military Union Solidarity and Development Party is widely expected to emerge as the largest bloc, in what critics say would be a rebranding of martial rule.

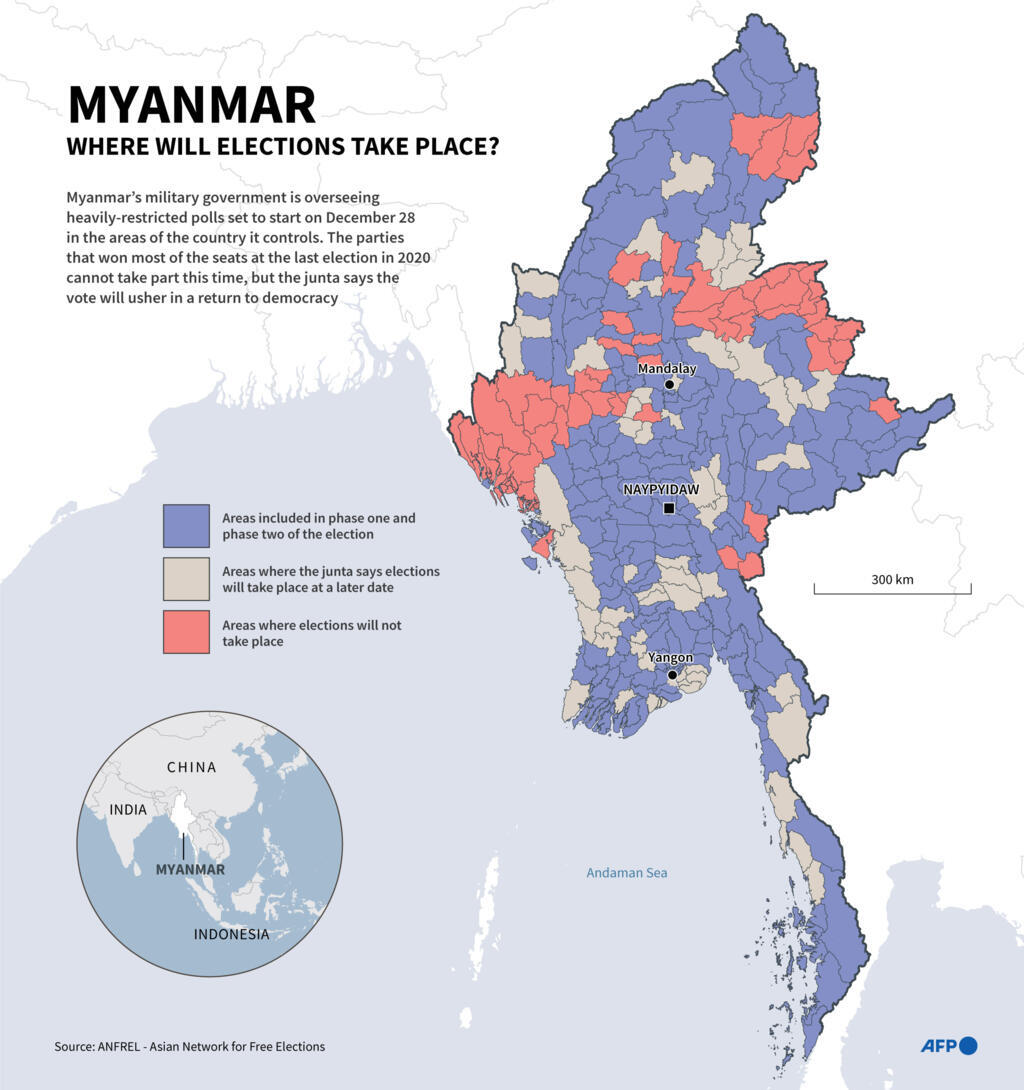

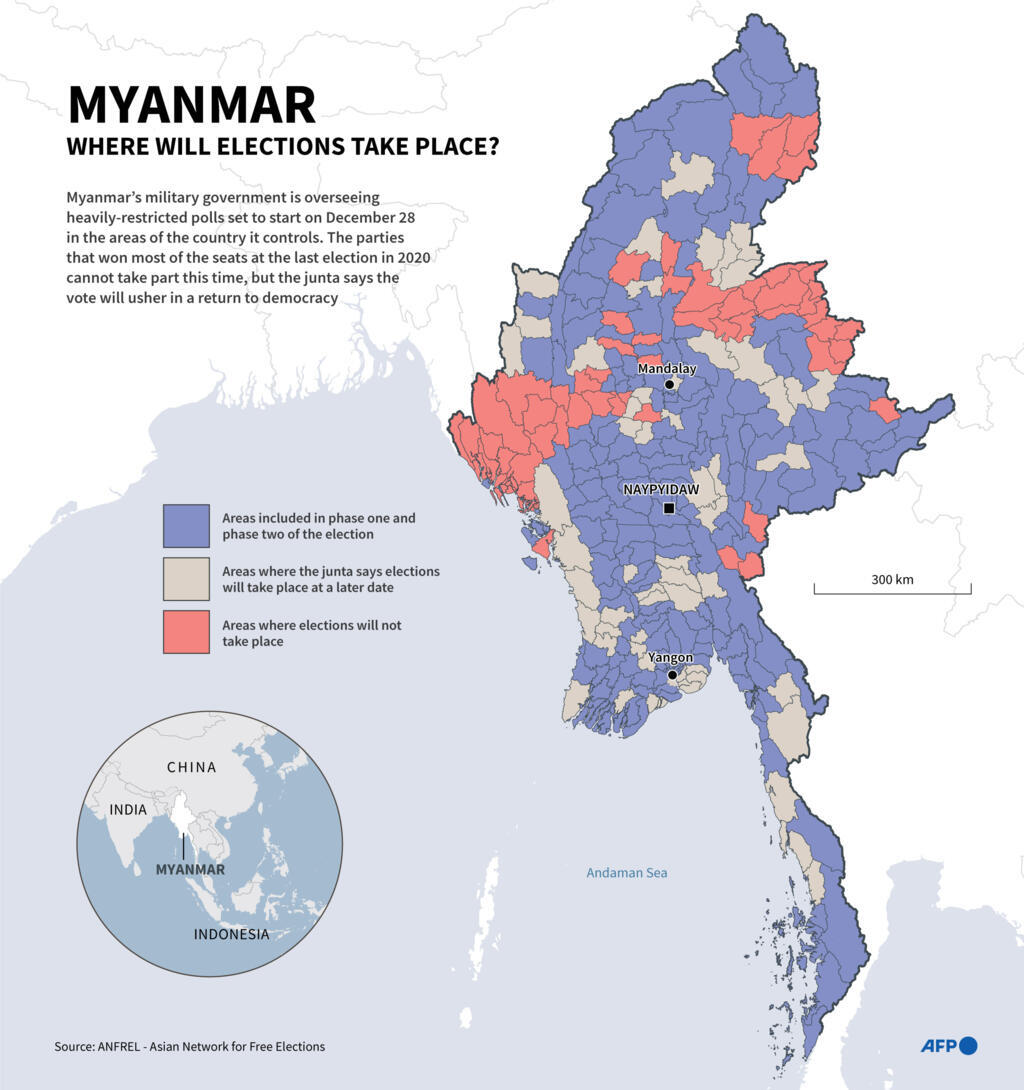

Myanmar: where will elections take place © Nicholas SHEARMAN / AFP

Myanmar: where will elections take place © Nicholas SHEARMAN / AFP

"We guarantee it to be a free and fair election," junta chief Min Aung Hlaing told reporters after casting his ballot in the capital Naypyidaw.

"It's organised by the military, we can't let our name be tarnished."

The Southeast Asian nation of around 50 million people is riven by civil war and there will be no voting in areas controlled by rebel factions that have risen up to challenge military rule.

While opposition factions threatened to attack the election, there were no reports of violence against polling day activities by the time voting ended at 4:00 pm (0930 GMT).

Limited turnout

Snaking queues of voters formed for the previous election in 2020, which the military declared void a few months later when it ousted Aung San Suu Kyi and seized power.

But when a polling station near her vacant home closed on Sunday, only around 470 of its roughly 1,700 registered voters had cast ballots, an election official said -- a turnout of less than 28 percent.

Its first voter, Bo Saw, 63, said the election "will bring the best for the country".

"The first priority should be restoring a safe and peaceful situation," he told AFP.

At a downtown Yangon station near the gleaming Sule Pagoda -- the site of huge pro-democracy protests after the 2021 coup -- 45-year-old Swe Maw dismissed international criticism.

"There are always people who like and dislike," he said at a polling station that later reported a turnout of below 37 percent.

The Southeast Asian nation of around 50 million is riven by civil war and there will be no voting in areas controlled by rebel factions © Lillian SUWANRUMPHA / AFP

The run-up saw none of the feverish public rallies that Aung San Suu Kyi once commanded, and the junta has waged a withering pre-vote offensive to claw back territory.

"I don't think this election will change or improve the political situation in this country," said 23-year-old Hman Thit, displaced by the post-coup conflict.

"I think the air strikes and atrocities on our hometowns will continue," he said in a rebel-held area of Pekon township in Shan state.

The run-up to the election saw none of the feverish public rallies that former civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi once commanded © Lillian SUWANRUMPHA / AFP

The military ruled Myanmar for most of its post-independence history, before a 10-year interlude saw a civilian government take the reins in a burst of optimism and reform.

However, Min Aung Hlaing snatched power in a coup, alleging widespread voter fraud, after Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy party trounced pro-military opponents in the 2020 elections.

The military put down pro-democracy protests and many activists quit the cities to fight as guerrillas alongside ethnic minority armies that have long held sway in Myanmar's fringes.

There is no official death toll for Myanmar's civil war and estimates vary widely, but global conflict monitoring group ACLED tallies media reports of violence and estimates that 90,000 people have been killed on all sides since the coup.

Aung San Suu Kyi is serving a 27-year sentence on charges that rights groups dismiss as politically motivated.

"I don't think she would consider these elections to be meaningful in any way," her son Kim Aris said from his home in Britain.

Vote 'disruption' banned

Most parties from the 2020 vote, including Aung San Suu Kyi's, have since been dissolved.

The Asian Network for Free Elections says 90 percent of the seats in the previous election went to organisations that did not appear on Sunday's ballots.

New electronic voting machines did not allow write-in candidates or spoiled ballots.

A voter shows an inked finger after casting a ballot © NHAC NGUYEN / AFP

The junta is pursuing prosecutions against more than 200 people for violating draconian legislation forbidding "disruption" of the poll, including protest or criticism.

The United Nations in Myanmar said it was "critical that the future of Myanmar is determined through a free, fair, inclusive and credible process that reflects the will of its people".

The second round of polling will take place in two weeks before the third and final round on January 25, but the junta has acknowledged that elections cannot happen in almost one in five lower house constituencies.

© 2025 AFP

Myanmar: where will elections take place © Nicholas SHEARMAN / AFP

Myanmar: where will elections take place © Nicholas SHEARMAN / AFP