Africa Deindustrializes Due To China’s Overproduction and Trump’s Tariffs

At the close of a year in which Africa’s underlying economic problems continue to worsen, the Johannesburg G20 summit on November 22-23 utterly failed in its mandate to cut the continent’s foreign debt and assure that appropriate climate-finance grants will be available. Nevertheless, even while the world economy’s value chains suffer disfigurement thanks to Donald Trump’s whimsical tariffs, ambitions for Africa’s long-overdue industrialization are regularly articulated based either on copying an East Asian sweatshop-based strategy replete with Special Economic Zones, given the continent’s large, young, desperate workforce; or on adding value to local raw materials.

In both cases, hope is sometimes expressed that, as U.S., British and European Union (EU) aid shrinks and trade barriers rise, the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) economies will come to the rescue, especially because a benign sponsor – Beijing – is standing by, quite capable of reversing current trends.

Writing in early December, Tricontinental research institute leader Vijay Prashad recalled how, “At the 2015 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Johannesburg, South Africa, the Chinese government and fifty African governments discussed the problem of economic development and industrialization. Since 1945, the question of African industrialization has been on the table but has not advanced due to the neocolonial structure that has prevented any serious structural transformation.”

True, colonial-era and immediate post-colonial African dependency relations persisted thanks to Western economies’ power over the continent’s exports, over global commodity markets and over nascent value chains through the fragmentation and extension of corporate production systems. Only a few sites of durable capital accumulation emerged in Africa via productive forces associated with manufacturing.

Prashad explains: “The most industrialized countries on the African continent are South Africa, Morocco, and Egypt, but the entire continent accounts for less than 2% of world manufacturing value added and only about 1% of global trade in manufactures. That is why it was so significant for FOCAC to put industrial policy at the heart of its agenda; its 2015 Johannesburg Declaration affirmed that ‘industrialization is an imperative to ensure Africa’s independent and sustainable development’.”

These are fine aspirations – and they are also expressed regularly in African elite meetings with Western imperial powers, such as in Angola last month when 76 leaders of the EU and African Union met for a major summit aiming to “Strengthen continental and regional economic integration and accelerate Africa’s industrial development.” Yada yada.

In practice, such sentiments tend to be overwhelmed by the capitalist mode of production’s laws of motion; today, especially by the unregulated, increasingly desperate drive for profit and commodity access by Chinese firms. A new book makes that case (with free download here): The Material Geographies of the Belt and Road Initiative, edited by Elia Apostolopoulou, Han Cheng, Jonathan Silver and Alan Wiig.

(For dialectical curiosity, here’s a completely different approach, from a neoliberal podcaster arguing that China’s ‘curse of overproduction’ is not capitalism’s fault but is due to “government’s heavy intervention, weak market mechanisms, and lack of legal frameworks perpetuate inefficiencies, with local governments chasing GDP through subsidies and projects.”)

In a more critical – but nationalistic (and non-solidaristic) – spirit, one of Prashad’s leading allies here in Johannesburg, Irvin Jim of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA), made a heartfelt appeal last month against “the dumping of cars from India and China” whose automakers have increased their market share here by a factor of 25 since 2018.

Hence, insists Jim, “it is about time that we must increase tariffs.” His grievances about massive job losses caused by imports – to be discussed in detail in the next essay – suggest Prashad is not yet attuned to deindustrialization damage done by the Chinese state and its capitalists in recent years. Moreover, at a time the West has shrunk its own (inflation-adjusted) aid-debt-investment packages, the FOCAC commitments made in 2015 – amounting to about $22 per African citizen – were chopped nearly in half by 2024.

Relentless Western abuse of Africa

Of course, Washington should mainly be blamed for the continent’s most current wave of social misery and economic degradation, which in the second half of 2025 contributed to Gen Z social uprisings in Kenya, Tunisia, Morocco, Madagascar, Zambia and Tanzania. The mix of Western economic attacks on Africa and greedy resource grabbing should not disguise how imperial interest at the White House and State Department is waning: Trump last week recalled 15 career-professional U.S. ambassadors from African countries, to be replaced by America-First political hacks.

Exceptions to that disinterest in Africa may arise, such as the Lobito Corridor extraction route for $2 trillion worth of minerals to be spirited out from the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) via an Angolan port. In a ‘peace deal’ earlier this month brokered by Trump between corruption-accused DRC leader Felix Tshisekedi and Rwandan dictator Paul Kagame – one immediately violated – the U.S. president announced he would soon be “sending some of our biggest and greatest companies over to the two countries… we’re going to take out some of the rare earth and take out some of the assets and pay… and everybody’s going to make a lot of money.”

Except the African people and ecologies, yet again victims of what can be termed ‘unequal ecological exchange.’

Already in February, Trump and his ex-South African sidekick Elon Musk had wiped out most U.S. emergency food, medical and climate-related aid to Africa, with a special cut for all South African contracts. Washington’s $64 billion US Agency for International Development was shuttered by Musk, fed “into the wood chipper,” leaving many millions of lives at risk (although some AIDS medicines spending was later revived).

Then came Trump’s devastating tariffs – in February, April and again in August – followed by the September demise of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) which since 2000 had given dozens of African countries duty-free access to U.S. markets. Notwithstanding a deeper context of dependency relations associated with AGOA – for as political economist Rick Rowden points out, “gains were largely due to African exports of petroleum and other minerals, not manufactured goods” – these latter trade-curtailing processes were exceptionally damaging, wiping out 87% of auto exports from South Africa in the first half of 2025.

The World Bank concluded of 2025’s tariff chaos, “industry-level impacts may be significant in global value chain–linked activities, notably, textiles and apparel as well as footwear (Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, and Mauritius) and automotive and components (South Africa)… Loss of the AGOA would sharply reduce exports to the United States. On average, exports would decline by 39% if a nation were suspended from AGOA benefits.”

(A House of Representatives bill may gain support to resume AGOA in 2026 but without the main industrial beneficiary, South Africa, due to Trump’s irrational hostility. Exports of autos, steel, aluminium and many agricultural products to U.S. have collapsed.)

Moreover, other Western sources of demand for African products will also soon decline, according to the World Bank, thanks to Europe’s “new regulatory measures, such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the EU Deforestation Regulation, [which] impose stringent compliance requirements on exporters of cement, metals, and agricultural products” starting in early 2026. The Bank admits both that a “global shift toward ‘friendshoring’ in strategic industries, risks marginalizing African suppliers” – thus undermining its export-led ‘growth’ mantra.

On the class-struggle front, the Bank continues, “The growth of the labor share in national income registered a negative contribution in 2000–19: it declined at an annual rate of 0.1%. This decline reflects the adoption of more capital-intensive technologies, increased participation in global value chains, reduced (relative) bargaining power of workers, and greater market power of large firms in concentrated product markets.”

Too much is being produced, mainly by China

Still, the overarching crisis affecting the world economy, not just Africa’s, can be termed the ‘overaccumulation of capital,’ which Karl Marx had in Das Kapital identified as the core internal problem capitalism faces, due to the tendency to overproduce relative to market size. From that process, we can understand geopolitical tensions much better.

As world-systems sociologist Ho-fung Hung recently suggested, “Today’s intensifying U.S.-China rivalry resembles more the inter-imperial rivalry a century ago driven by the overaccumulation of rising capitalist power – that is China – than the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.”

At the end of 2025, it is abundantly evident that far too much productive capacity exists in China, given limits to the fractured world economy’s ability to mop up the surpluses through various forms of consumption and debt – now at saturation level in many countries.

The excess capacity is experienced in various ways, as capital flows away from durable fixed investment in many settings, and often into extreme financial bubbling due to higher speculative profits. When the crash comes, if the state is sufficiently strong, such credit flows can be reversed, as Evergrande’s 2021-22 collapse in China illustrates (following which the state’s managers of overaccumulated capital self-destructively redirected bank loans to manufacturing again).

Nervousness about the durability of the financialization that inevitably follows overproduction is reflected in the soaring gold price, up from $250/oz 25 years ago to an insane $4500/oz today. There is also new evidence, in many national economies, of fresh swathes of deindustrialization, high levels of unemployment and under-employment, and falling profit rates.

Mostly though, excess capacity is the core signal, as some crucial sectoral examples show:

- global steel output of nearly 1.9 billion tonnes in 2024 contrasted to 2.47 billion tonnes of capacity (i.e., 76% capacity utilization), with a rise of another 10% excess capacity estimated in 2025, to 680 megatonnes;

- in chemicals, Bloomberg News reported earlier this month, “A wave of new Chinese petrochemical plants is raising fears of a deluge of exports that will put pressure on other producing nations that are already struggling with oversupply” due to “seven massive petrochemical hubs… creating a global glut that could swell even further if more planned plants come online” at a time, in 2025, polyethylene output rose 18%;

- China’s annual vehicle production capacity – carrying either internal combustion engine or electric motors – was 55.5 million vehicles/year capacity in 2024, but was only half utilized (just 27.5 million vehicles were produced that year), while in 2025, Chinese output was expected to reach 35 million (still a low capacity utilization), displacing other economy’s sales and leaving the world with increased idle capacity, as global vehicle sales languish at 90 million;

- also in China, “The root cause of the cement sector’s current difficulties lies in the long-standing problem of overcapacity, which has now been amplified by weaker market demand” since 2021 “due to declining property investment and a slowdown in infrastructure construction,” according to the China Building Materials Federation, and

- solar photovoltaic panels generated nearly 600 GW of new power in 2024 – mostly emanating from China – but there was, at that point, more than 1,000 GW of annual manufacturing capacity, and to store the power, lithium-ion batteries were produced at the scale of 2.5 TWh in 2023, but by 2024 there was 3 TWh of capacity and projections of 9 TWh by 2030, at a time demand was expected to rise only to 5 TWh.

(Renewable energy offers a curious form of capitalist ‘excess capacity’ – since this description obviously deserves scare quotes: for the sake of ecological sanity, it is a misnomer. So much more capacity is urgently needed for installation in every corner of the earth, but at an affordable price. And it’s becoming obvious that even mass production in China apparently cannot drive prices down to the point where capitalism can save itself from the climate catastrophe, given this disjuncture.)

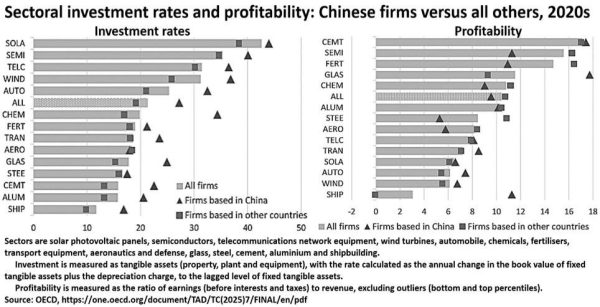

As a result of core sectoral overinvestment, financial bubbling and trade turmoil, world capitalism is currently suffering the worst case of overaccumulation in recorded economic history. In a recent report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the extent of recent overproduction emanating from China is illustrated by comparing investment rates of its firms (and also multinational corporate subsidiaries there) to sites elsewhere. China’s economy takes obvious leadership in ‘new economy’ sectors, amidst an overall investment boom that followed Beijing’s recent redirection of bank lending into manufacturing.

However, whether this investment can be justified by sustained profitability remains to be seen, for as the OECD shows, China’s rates are generally lower overall than in other countries, and especially in several (mainly old-economy) sectors including semiconductors, fertilizers, chemicals, aluminium, steel, and aeronautics and defense.

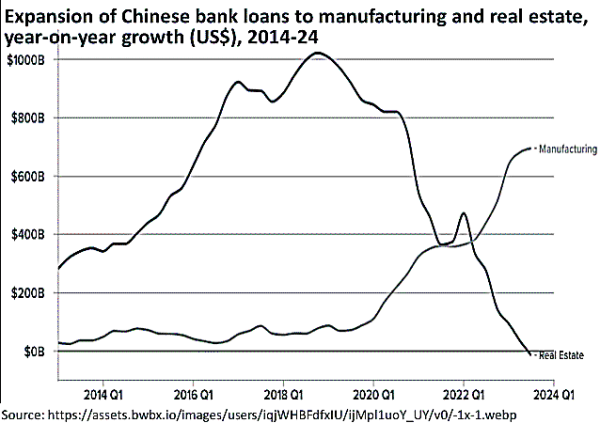

One reason for the overproduction of those goods, is the Chinese state’s ambition and ability to redirect credit flows (often at below-market rates), as can be seen in the year-on-year growth in Beijing’s (centrally-directed) lending to its own firms. This is a revealing case in which public policy amplifies capitalism’s underlying contradictions (the classic ‘pro-cyclical’ bias of neoliberalism). So after the early-2019 year-on-year increases in lending to China’s bubbly real estate sector hit $1 trillion, at the peak of the economy’s chaotic property speculation, then, contributing to the bubble’s burst, loans fell rapidly in 2021, down to no year-on-year growth by early 2024.

In contrast, year-on-year growth in Chinese manufacturing finance rose from steady levels of just $60-90 billion in the 2016-20 period; and suddenly by late 2023 there were $700 billion worth of new manufacturing loans (compared to the year before).

These trends appear to have continued, if the People’s Bank of China statistics are accurate; in September its staff reported that “outstanding medium and long-term loans to the manufacturing sector registered a year-on-year increase of 15.9%. Specifically, outstanding loans to the high-tech manufacturing sector increased by 13.4% year on year.”

Hence in 2024-25, manufacturing output in China has been formidable, growing nearly 6% annually (more than ten times the 0.6% global manufacturing increase in 2024 and three times 2025’s expected increase of 1.9%). The result is a 2025 trade surplus that, for the first time, exceeded $1 trillion.

But it is vital to keep the systemic features in mind, because in this process of serving capitalist global value chains, “China has made large transfers in value through trade and investment to the imperialist bloc,” according to Marxist economist Michael Roberts.

This is obvious enough, but so too have peripheral countries like the DRC made large transfers in value to Chinese capitalism through, first, Congolese workers’ depletion of non-renewable resources that are inadequately compensated (either through royalties or various forms of profit reinvestment), thus depriving current and future generations of natural wealth; second, through massive greenhouse gas emissions whose cost we consider below; and third, through local pollution which in many cases can be extreme. All these features contribute to China’s role as a subimperial power.

Can Chinese-led industrialization save Africa?

How does China address its excessive local investment and untenable trade surpluses? One obvious strategy implemented since the early 2010s is when firms attempt so-called ‘going out’ from their immediate sites of overaccumulation, along the Belt and Road Initiative. This has included the establishment of much stronger connections to African markets, which should in turn permit more African exports.

This process coincides, insists Ho-fung Hung, with “the increasing competition between Chinese capital and U.S. capital worldwide after China started to aggressively export its overaccumulated capital to the rest of the world in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008.”

In contrast, on the optimistic end of the spectrum, Prashad argues, “China’s industrial capacity would be put at the service of Africa’s need for industrialization through the creation of joint ventures, industrial parks, a cooperation fund, and mechanisms for technology and science transfer. Africa-China trade has increased from $10 billion in 2000 to $282 billion in 2023. In 2024, the Chinese government upgraded its relationship with African states to ‘strategic partnerships’, enabling greater cooperation. We now have a test case for whether South-South cooperation can engender sovereign industrialization that breaks with the old patterns of plunder and dependency.”

But on the pessimistic end, there are too many instances of adverse impacts from Chinese capitalism in Africa: deindustrialization through swamping local markets with surpluses (as NUMSA complains), especially as the displacement of Trump’s tariffs; broken promises on Special Economic Zone investments; brazen but unpunished corruption; excessive lending and then sudden cuts in credit lines; and heinous corporate behavior especially in the extractive industries, including extreme ecological damage. Each needs elaboration, in the pages below.

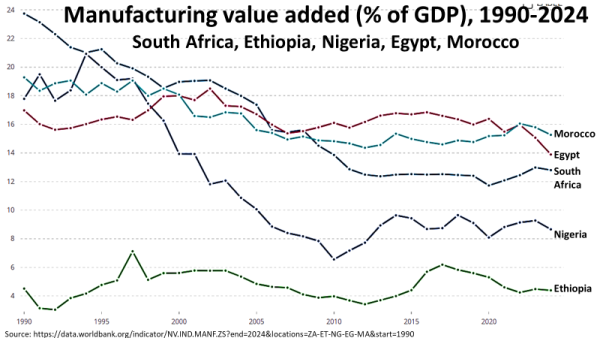

And one test case deserves more consideration: the rapid deindustrialization of South Africa underway in recent months thanks to the ‘dumping’ (i.e. sale at below the cost of production) of Chinese overaccumulated capital, according not only to the government in Pretoria – which in recent months punished imported Chinese steel, tyres, washing machines, and nuts and bolts with new tariffs – but also to NUMSA (which wants the same for cars), although it is ordinarily very pro-China. In South Africa, the manufacturing/GDP ratio was 24% in 1990 and has now sunk to 13%.

Formidable Chinese product competition means the African economies mentioned by Prashad as the continent’s lead industrial production sites, plus the largest in population (Nigeria), have not improved their manufacturing/GDP ratios since that 2015 FOCAC industrialization hype. Most such ratios, like South Africa’s, had already collapsed in the first round of 1990s-era trade liberalization.

The optimal test case that many pointed to during the mid-2010s as Africa’s cutting-edge industrialization site, was Ethiopia, thanks to the sudden emergence of (largely sweatshop) manufacturers mainly in Addis Ababa, whose products benefited from the new train line to the port of Djibouti, built with the assistance of Beijing. As a result of the influx of Chinese firms’ local production of clothing, textiles, footwear and other light-industrial output, Ethiopia’s manufacturing/GDP rose rapidly from 3.4% at the low point in 2012, to 6.2% in 2017.

However, that ratio subsequently fell to 4.3% in the period 2021-24. As the International Monetary Fund explained, “The share of manufactured goods such as textiles, leather and meat product in total exports had grown to 13.5% in Fiscal Year 2018/19, from a small base, but declined sharply thereafter to around 4% in the first nine months of FY2024/25, due to the pandemic, conflict, suspension from AGOA, and foreign exchange shortages that limited availability of intermediate imports.”

Those hard currency shortages led to a major financial crisis in late 2023, when the Addis Ababa regime declared bankruptcy on foreign loans, just days before the country officially joined the BRICS network. As a result of the default, Ethiopia was initially not permitted to become a formal member of the BRICS New Development Bank, for potential hard-currency credit infusions (nearly 80% of that bank’s lending is in the dollar or euro), although it is scheduled to join, at some stage.

Then in mid-2024, a $2.56 billion International Monetary Fund package imposed all the classical Washington Consensus remedies on Ethiopians, including a 50% currency depreciation which was meant to spur manufacturing exports. Indeed a revival of sweatshop exports oriented to Chinese consumer markets apparently began in 2025, and Beijing began talks to potentially convert $5.4 billion of its dollar-denominated loans to Ethiopia into yuan by late 2025, on which a lower interest rate would be paid. Ethiopia was indebted to China for $7.4 billion of its $28 billion foreign debt in late 2023 (with $15.3 billion owed to international financial institutions).

But in Ethiopia, and across Africa more generally, foreign exchange reserves have shrunk due to the vicissitudes of Global North states and multilaterals. For all recipients, aid was cut in 2024 by 9%, and in 2025 by up to 17%. The peak year for Overseas Development Aid to Africa was 2020 at $73 billion, but especially since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, European capitals and London have replaced a great deal of aid for Africa with higher military budgets.

Will Beijing step in? In aggregate, Chinese aid, investment and loans to Africa have also fallen since mid-2010s peaks, which also affected states’ foreign exchange reserves. China’s own new public and publicly-guaranteed loans to Africa collapsed from $32 billion in the peak year of 2016, to $1 billion in 2022. The year-end 2025 African foreign debt of $1.3 trillion includes $182 billion in Beijing’s known public and publicly-guaranteed loans.

China had taken a decision in 2021, AidData researchers remind, to fund 128 rescue loan operations in 22 low-income countries facing debt distress, costing $240 billion. These included five African states – Angola, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania and Kenya – among which low-income borrowers were “typically offered a debt restructuring that involves a grace period or final repayment date extension but no new money, while middle-income countries tend to receive new money – via balance of payments (BOP) support – to avoid or delay default… These operations include many so-called ‘rollovers,’ in which the same short-term loans are extended again and again to refinance maturing debts.”

The 2024 FOCAC did, however, denominate more financial flows in the Chinese currency, which could facilitate trade, alleviate forex shortages, and also lower transactions costs. Yet devils are in the details, for against all the logic argued above, according to the Centre for Global Development (which is generally neoliberal and welcomes Chinese lending):

“Between 2015 and 2021, commercial creditors contributed about a third of all Chinese lending commitments over that period. These commercial lenders overtook policy banks between 2018 and 2021 … [and] are market-oriented, with loans that are more expensive and with shorter maturity than state-owned counterparts. Their need for risk mitigation, usually through Sinosure, raises the financing costs even higher. Over the next five years, a continuation of this trend where Chinese commercial lenders become an ever-larger segment of lending to Africa at non-concessional rates will only heightens the risks of debt distress.”

So the overall trends suggest that China’s extreme overaccumulation of manufacturing this year, as Trump’s tariffs cause chaos at a time of Belt & Road Initiative burn-out, there is no reason to expect FOCAC to, as Prashad hopes, “engender sovereign industrialization that breaks with the old patterns of plunder and dependency.” Africans should prepare for the opposite.

FOCAC’s declining pledges, 2006-24

| FOCAC cycle | Nominal pledge (US$bn) | Inflation-adjusted pledge (2024 US$bn) | Annualized (2024 US$bn/yr) | African population (bn) | Per capita (2024 US$/person/yr) |

| 2006 | 5.0 | 7.78 | 2.59 | 0.952 | 2.72 |

| 2009 | 10.0 | 14.62 | 4.87 | 1.028 | 4.74 |

| 2012 | 20.0 | 27.33 | 9.11 | 1.10 | 8.28 |

| 2015 | 60.0 | 79.41 | 26.47 | 1.220 | 21.69 |

| 2018 | 60.0 | 74.95 | 24.98 | 1.310 | 19.07 |

| 2021 | 40.0 | 46.31 | 15.44 | 1.394 | 11.08 |

| 2024 | 50.7 | 50.70 | 16.90 | 1.495 | 11.31 |

Source: http://www.focac.org/eng/

Also adversely affecting Africa’s hard currency revenues, most energy and mineral commodity markets crashed after their May 2022 peaks (with notable exceptions like gold and, recently, platinum). As a result, across the continent, there is less foreign exchange available to repay debt, especially when exacerbated by the higher interest rates imposed by the U.S. Federal Reserve from 2022-24.

In 2025, Trump’s new tariffs on African exports to the U.S. represented an overall 10% levy in April, followed by higher amounts for many countries in August (e.g. South Africa at 30%). Annual remittances, generally paid by African migrant workers living in countries abroad to their family back home, rose in this period from $66 billion up to $110 billion in 2024, but are not expected to rise further due to rising Western xenophobia.

Are Chinese firms looting Africa?

In this desperate context, Ethiopia’s sweatshop experience could not be termed genuinely ‘sovereign industrialization,’ no doubt Prashad would agree. Nor should any African – or sympathetic observer – tolerate the Chinese-led extractive industry plunder of many economies, resulting not only in extreme ecological damage in general terms, but in a series of specific scandals and social resistance.

As noted above, there are usually three categories to consider, of ecological reparations due to non-renewable resource depletion, greenhouse gas emissions and other forms of localised pollution. Michael Roberts acknowledges, in a helpful essay on environmentalism, “a continual battle by capital to control and lower rising raw material prices as natural resources are depleted and not renewed, adding another factor to the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.”

And in a 2021 co-authored analysis of the ‘Economics of Modern Imperialism’, Roberts argues,

“Colonialism and modern imperialism do not exclude each other. Colonialism is the appropriation of natural resources, military occupation, the direct state control of colonies and the stealing by the imperialist countries of commodities not produced capitalistically. But colonialism contains in itself the germs of modern imperialism. This is the appropriation by capitals in the imperialist countries of the surplus value produced by capitals in the colonies through the trade of the commodities with high technological content produced in the imperialist countries for the capitalistically produced raw materials or industrial goods produced with lower technological content in the dominated countries. The result is unequal exchange, the appropriation of international surplus value through international trade.”

Roberts concludes that the Chinese economy therefore retains a relatively low – and now fast-falling – share of global value chain profits due to unequal exchange processes. The distribution, marketing, financing and research and development departments of Western corporate headquarters squeeze out monies that could otherwise be paid to both Chinese and Congolese laborers and to communities now underpaid for their work in extraction of raw materials, in super-exploitative production systems, and in goods transport.

There are some on the left who object to a critique based in part upon imperial-subimperial collaboration in the looting of Africa. Last year, Prashad’s colleagues at Tricontinental offered a different view of the DRC, based on competition between the Chinese on the one hand; and on the other, Western firms like Swiss-headquartered, London-listed Glencore (whose largest share of its $70 billion capitalization is actually registered on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange) and Canada’s Ivanhoe. Tricontinental authors claim that “Chinese interests therefore lie in keeping mineral and metal processing within the DRC and building an industrial base for the country.”

This counter-intuitive conclusion is based on how, in Tricontinental’s interpretation, “The entry of the Chinese state and private Chinese companies into Africa over the past two decades has provided competition against the Global North countries and their mining companies. This was the first time that these multinational corporations faced direct competition, a shift that provided the space for the Congolese government to amend the mining code in 2018 on more beneficial terms.”

Admitting that, in the process, Chinese firms gained “control of fifteen of the DRC’s seventeen mining complexes,” Tricontinental authors turn to this justification: “In the extractivism debate, the Global North, its eyes set on furthering its own agenda, has fixated on China’s role in the region as the world’s leading consumer of cobalt, nearly 80% of which it uses in its rechargeable battery industry. What is often left out of the discussion, however, is that, as the largest manufacturing country in the world, China uses Congolese minerals and metals to produce goods that are consumed across the globe, including in the DRC and the Global North.”

Indeed this subimperial location within global value chains makes China subject to an unequal ecological exchange critique. For behind the general need for resource extraction and (limited) processing of minerals that goes on in Africa, are scandalous conditions. Without sinking into Sinophobia, it is useful to recall some of the highest-profile cases, because Beijing simply fails to respond to the obvious need to curtail Belt and Road abuse by Chinese firms:

- in the DRC in November, Congo Dongfang International Mining leaked toxic pollution into the Lubumbashi River near the country’s second largest city, while nearby at Kalando, informal miners (75% of whom across the DRC sell their wares to Chinese buyers) suffered at least 50 deaths in a mountainside collapse that compelled the government to ban artisanal copper and cobalt mineral processing, in the wake of non-payment of billions of dollars’ worth of royalties to the government by Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, Ningxia Orient, JiuJiang JinXin and Jiujiang Tanbre smelters – all within Apple’s supply chain – which in turn resulted in a major lawsuit by the Kinshasa regime and by a U.S. public interest agency against the California corporation, and similar non-payment accusations were made by Kinshasa officials against China Molybdenum’s super-exploitative Tenke Fungurume cobalt mine;

- in Zambia’s copperbelt in February, negligence by Sino-Metals Leach and NFC Africa Mining caused a slime-dam break – of 1.5 million tonnes of cyanide- and arsenic-laced sludge – into the Kafue River, resulting in an $80 billion lawsuit by some of the 700,000 affected residents adjacent to Zambia’s main internal waterway and second-largest urban region;

- in the Central African Republic’s mines, there was slave-like human trafficking of Nigerians – who went unpaid for a year in 2024-25 – by Rado Central Coal Mining Company;

- in Ghana, Shaanxi Mining extracted gold in a manner that amplified the ‘galamsey’ artisanal mining crisis;

- in Zimbabwe, there are countless complaints against Chinese mines, for looting $13 billion of Marange diamonds by the military-owned parastatal Anjin (as even President Robert Mugabe alleged in 2016), for the murder of a dozen Mutare artisanal gold miners in 2020 by Zhondin Investments, for mass displacement and pollution at the Hwange coal mine by Beifa Investments, for illegal mining in national parks by Afrochine Energy and Zimbabwe Zhongxin Coal Mining Group, and for Sinomine Resource Group’s failure to respect beneficiation requirements at the continent’s largest lithium mine, in Bikita, in addition to other Chinese lithium miners at Kamaviti, where as a result, Centre for Natural Resource Governance director Farai Maguwu alleged in late December, “Zim is the biggest donor to China, and not the other way round”;

- in South Africa, the corruption of rail parastatal Transnet by Chinese locomotive suppliers empowered the notorious Gupta ‘state capture’ family, while at two chaotic Special Economic Zones, Chinese investors included an Interpol red-listed looter of a Zimbabwean mine and two auto producers (FAW and BAIC) whose job creation and production promises were not kept; and

- in the two main oil and gas controversies in Africa, state-owned China National Overseas Oil Corporation is building a heated pipeline (the world’s longest) from western Uganda to Tanzania’s port of Dar es Salaam, and state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation’s participation (with partners ExxonMobil and ENI) invested in a long-delayed northern Mozambican ‘blood methane‘ gas extraction project, in the midst of a civil war with Islamic guerrillas that since 2017 has displaced one million people and killed many thousand – and in both cases, the ultra-corrupt TotalEnergies leads the projects.

In addition to often-extreme human rights violations, these represent obvious forms of unequal ecological exchange, in which African economies lose net wealth, even if Chinese purchases of raw materials raise levels of foreign exchange and national income, creating (low-paid) jobs and providing a modicum of royalties, taxes and infrastructure.

Typically outweighing such benefits, though, damage is not limited to local pollution and displacement, or to permanent depletion of non-renewable resources that leave both current and future generations impoverished. For example, instead of burning coal, gas and oil, their hydrocarbons should be left underground and only later, if needed, exploited for non-combustible purposes (lubricants, synthetic materials, pharmaceutical products, etc).

On top of this damage, the extraction and processing of minerals also entail an enormous ‘social cost of carbon’ caused by CO2 and methane emissions in mines and smelters. This should be priced (by taxation not carbon trading) in the region of $1584/tonne of CO2 (according to a recent National Bureau of Economic Research study), rendering a great deal of the pollution-intensive extractive+processing activity as uneconomic.

The latter damage will create new ‘polluter-pays’ climate debtors out of low-income African economies, if the International Court of Justice’s July 2025 advisory opinion on liabilities for socio-ecological reparations is to be taken seriously. Following the court’s finding against states which do not limit their firms’ emissions, much more climate-debt litigation is inevitable. In late 2024, Beijing and many other high-polluting countries’ governments had opposed any liability judgement because, as the imperialist and subimperial powers together insisted, the Paris Climate Agreement “does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation.”

The best opportunity for a Chinese climate debt payment to Africa arose in September 2021 when Xi Jinping announced, “China will step up support for other developing countries in developing green and low-carbon energy, and will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad.”

However, not only is renewable energy still a for-profit commodity, unaffordable for the vast majority. In addition, in Zimbabwe, residents of the wretched coal-mining town of Hwange (near Victoria Falls) know that Xi’s was just one more broken climate promise, what with several Chinese coal-fired power plants under construction there.

In sum, unless the Chinese state suddenly begins regulating its firms’ emissions and abuse of African resources and people, and finds creative ways to pay a wide range of ecological reparations, it appears extremely unlikely that a genuine industrialization initiative will emanate from Chinese investors.

But having set the context of blame for Africa’s recent bout of underdevelopment both in Chinese overproduction and Trump’s tariffs – among the main new factors that amplify existing problems of commodity export dependency, excessive debt, structural adjustment policies and climate damage – the next essay will have to assess various strategies emerging among some leading African activists, ranging from nationalistic dirty growth to internationalist degrowth en route to eco-socialism.