What’s at Stake in Trump’s Executive Order Aiming to Curb State-Level AI Regulation

Photo by Cash Macanaya

December 31, 2025

President Donald Trump signed an executive order on Dec. 11, 2025, that aims to supersede state-level artificial intelligence laws that the administration views as a hindrance to innovation in AI.

State laws regulating AI are increasing in number, particularly in response to the rise of generative AI systems such as ChatGPT that produce text and images. Thirty-eight states enacted laws in 2025 regulating AI in one way or another. They range from prohibiting stalking via AI-powered robots to barring AI systems that can manipulate people’s behavior.

The executive order declares that it is the policy of the United States to produce a “minimally burdensome” national framework for AI. The order calls on the U.S. attorney general to create an AI litigation task force to challenge state AI laws that are inconsistent with the policy. It also orders the secretary of commerce to identify “onerous” state AI laws that conflict with the policy and to withhold funding under the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment Program to states with those laws. The executive order exempts state AI laws related to child safety.

Executive orders are directives to federal agencies on how to implement existing laws. The AI executive order directs federal departments and agencies to take actions that the administration claims fall under their legal authorities.

Big tech companies have lobbied for the federal government to override state AI regulations. The companies have argued that the burden of following multiple state regulations hinders innovation.

Proponents of the state laws tend to frame them as attempts to balance public safety with economic benefit. Prominent examples are laws in California, Colorado, Texas and Utah. Here are some of the major state laws regulating AI that could be targeted under the executive order:

Algorithmic discrimination

Colorado’s Consumer Protections for Artificial Intelligence is the first comprehensive state law in the U.S. that aims to regulate AI systems used in employment, housing, credit, education and health care decisions. However, enforcement of the law has been delayed while the state legislature considers its ramifications.

The focus of the Colorado AI act is predictive artificial intelligence systems, which make decisions, not newer generative artificial intelligence like ChatGPT, which create content.

The Colorado law aims to protect people from algorithmic discrimination. The law requires organizations using these “high-risk systems” to make impact assessments of the technology, notify consumers whether predictive AI will be used in consequential decisions about them, and make public the types of systems they use and how they plan to manage the risks of algorithmic discrimination.

A similar Illinois law scheduled to take effect on Jan. 1, 2026, amends the Illinois Human Rights Act to make it a civil rights violation for employers to use AI tools that result in discrimination.

On the ‘frontier’

California’s Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act specifies guardrails on the development of the most powerful AI models. These models, called foundation or frontier models, are any AI model that is trained on extremely large and varied datasets and that can be adapted to a wide range of tasks without additional training. They include the models underpinning OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini AI chatbots.

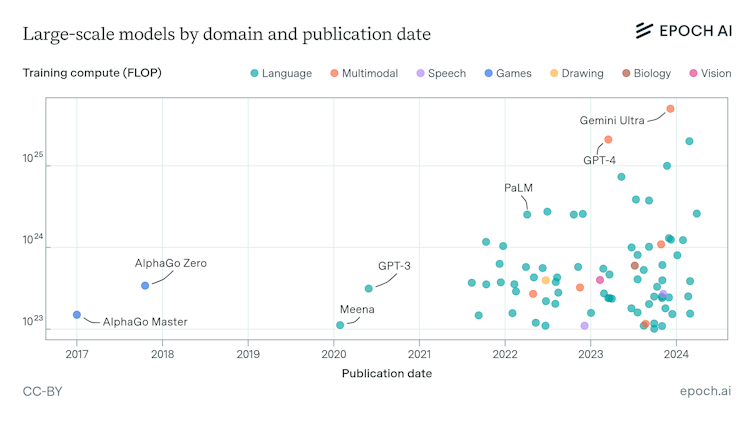

The California law applies only to the world’s largest AI models – ones that cost at least US$100 million and require at least 1026 – or 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 – floating point operations of computing power to train. Floating point operations are arithmetic that allows computers to calculate large numbers.

Robi Rahman, David Owen and Josh You (2024), ‘Tracking large-scale AI models.’ Published online at epoch.ai., CC BY

Machine learning models can produce unreliable, unpredictable and unexplainable outcomes. This poses challenges to regulating the technology.

Their internal workings are invisible to users and sometimes even their creators, leading them to be called black boxes. The Foundation Model Transparency Index shows that these large models can be quite opaque.

The risks from such large AI models include malicious use, malfunctions and systemic risks. These models could potentially pose catastrophic risks to society. For example, someone could use an AI model to create a weapon that results in mass casualties, or instruct one to orchestrate a cyberattack causing billions of dollars in damages.

The California law requires developers of frontier AI models to describe how they incorporate national and international standards and industry-consensus best practices. It also requires them to provide a summary of any assessment of catastrophic risk. The law also directs the state’s Office of Emergency Services to set up a mechanism for anyone to report a critical safety incident and to confidentially submit summaries of any assessments of the potential for catastrophic risk.

Disclosures and liability

Texas enacted the Texas Responsible AI Governance Act, which imposes restrictions on the development and deployment of AI systems for purposes such as behavioral manipulation. The safe harbor provisions – protections against liability – in the Texas AI act are meant to provide incentives for businesses to document compliance with responsible AI governance frameworks such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework.

What is novel about the Texas law is that it stipulates the creation of a “sandbox” – an isolated environment where software can be safely tested – for developers to test the behavior of an AI system.

The Utah Artificial Intelligence Policy Act imposes disclosure requirements on organizations using generative AI tools with their customers. Such laws ensure that a company using generative AI tools bears the ultimate responsibility for resulting consumer liabilities and harms and cannot shift the blame to the AI. This law is the first in the nation to stipulate consumer protections and require companies to prominently disclose when a consumer is interacting with generative AI system.

Other moves

States are also taking other legal and political steps to protect their citizens from the potential harms of AI.

Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis said he opposes federal efforts to override state AI regulations. He has also proposed a Florida AI bill of rights to address “obvious dangers” of the technology.

Meanwhile, the attorneys general of 38 states and the attorneys general of the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, American Samoa and the U.S. Virgin Islands called on AI companies, including Anthropic, Apple, Google, Meta, Microsoft, OpenAI, Perplexity AI and xAI, to fix sycophantic and delusional outputs from generative AI systems. These are outputs that can lead users to become overly trusting of the AI systems or even delusional.

It’s not clear what effect the executive order will have, and observers have said it is illegal because only Congress can supersede state laws. The order’s final provision directs federal officials to propose legislation to do so.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.