Funny thing synchronicity. No sooner had I finished this mornings rant here about Aid and Free Trade than I should find this article in the latest issue of Monthly Review, the Independent Socialist monthly from the U.S. It too refers to Easterly and the neo-liberal arguments for trade not aid and its distortions of the market in Africa. It is available on line.

REVIEW OF THE MONTH

Empire of Oil: Capitalist Dispossession and the Scramble for Africa

Michael Watts

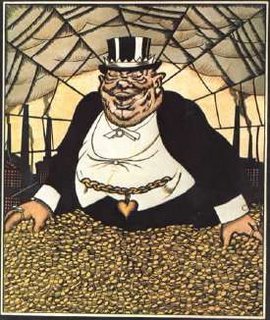

William Easterly, former high-ranking World Bank apparatchik, in his new lacerating demolition of structural adjustment—“a quarter century of economic failure and political chaos”—boldly states that the entire unaccountable enterprise of planned reform is “absurd” (http://www.nyu.edu/fas/institute/dri/Easterly/). It was Africa after all that was the testing ground for the Hayekian counter-revolution that swept through development economics in the 1970s. It began with the publication of Accelerated Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Agenda for Action (known as the “Berg Report”), the first in a series of World Bank reports that focus on the development problems of sub-Saharan Africa. This was the first systematic attempt to take the Chicago Boys experience in post-Allende Chile and impose it on an entire continent. The ideas of Elliot Berg and his fellow travelers marked the triumph of a long march by the likes of Peter Bauer, H. G. Johnson, and Deepak Lal (ably supported by the monetarist think tanks such as the Institute of Economic Affairs and the Mont Pelerin Society, and the astonishing rise to power from the early presence of Leo Strauss and Fredrich Hayek of the “Chicago School”) through the development institutions like the World Bank. Long before shock therapy in Eastern Europe or even the debt-driven “adjustments” in Latin America, it was sub-Saharan Africa that was the playground for neoliberalism’s assault. According to the United Nations, twenty-six of thirty-two sub-Saharan states had a “liberal” economic regime by 1998. Almost all had experienced some sort of structural adjustment program in the wake of the Berg report.

The neoliberal tsunami broke with a dreadful ferocity on African cities, and the African slum world in particular. Reform—the privatization of public utilities creating massive corporate profits and a decline in service provision, the slashing of urban services, the immiseration of many sectors of the public workforce, the collapse of manufactures and real wages, and often the disappearance of the middle class—was remorselessly anti-urban in its effects, as Mike Davis documents in Planet of Slums (Verso, 2005). As a consequence, African cities confronted the horrifying realities of an economic contraction of 2–5 percent per year combined with sustained population growth of up to 10 percent per annum (Zimbabwe’s urban labor market grew by 300,000 per year in the 1990s while urban employment grew by just 3 percent of that figure).The neoliberal tsunami broke with a dreadful ferocity on African cities, and the African slum world in particular. Reform—the privatization of public utilities creating massive corporate profits and a decline in service provision, the slashing of urban services, the immiseration of many sectors of the public workforce, the collapse of manufactures and real wages, and often the disappearance of the middle class—was remorselessly anti-urban in its effects, as Mike Davis documents in Planet of Slums (Verso, 2005). As a consequence, African cities confronted the horrifying realities of an economic contraction of 2–5 percent per year combined with sustained population growth of up to 10 percent per annum (Zimbabwe’s urban labor market grew by 300,000 per year in the 1990s while urban employment grew by just 3 percent of that figure).

What is especially striking is that the fear that Africa was largely marginal to the circuits of capitalist accumulation and global resource flows during the 1980s and might be marginalized further, in some respects, proved to be a massive understatement. It is almost shocking to think that in the 1970s, Africa accounted for 25 percent of FDI to the third world. By 2000 it had crashed to 3.8 percent (Africa’s share of world FDI is currently less than 1 percent).

It is no surprise that against this backdrop the development establishment flails around wildly. On the one side stands former World Bank economist William Easterly for whom all aid (“planning”) has been a total (and unaccountable) failure. The solution is not to plan at all. Rather than planners—in his view the IMF/IBRD stenographers are really Stalinists in neoliberal garb—and the likes of Bono and Tony Blair, we need to find a raft of “searchers” like microcredit guru Mohammed Yunus. On the other stands the one-man industry otherwise known as Jeffrey Sachs who seeks to expand foreign aid—$30 billion a year for Africa—and to initiate a Global Compact by which “the rich will help save the poor,” who are as much hampered by poor physical geography as governance failure.

The African accumulation crisis, and the dynamics of capital and trade flows, are in practice complex and uneven. In addition to oil (and the very few cases of manufacturing growth in places like Mauritius which are little more than national export-processing platforms), the other source of economic dynamism is the (uneven) emergence of global value chains. This can be seen especially in relation to high-value agricultures (fresh fruits and vegetables) in South Africa, flowers in Kenya, green beans in Senegal. Such forms of contract production, typically buyer-driven commodity chains in which retailers exert enormous power, have created islands of agrarian capitalism that contribute to and deepen patterns of existing inequality across Africa and further the interests of business elites, which are often not African. The deepening of commodification in the countryside in tandem with demographic pressures (caused as much by civil war and displacement as high fertility regimes) has made land struggles a vivid part of the new landscape of African development.See:

Africa

Neo-Liberalism

Aid

Oil

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

MonthlyReview, Africa, neo-liberalism, ChicagoSchool, oil

Aid, development, CATO P3, state-capitalism, capitalism, industrialization, Easterly, Bauer, banks, IMF, NGO, Fordism, Marx, trade, free-trade, Third-World,

No comments:

Post a Comment