Author:

Laila Shadid

2022 REPORTING FELLOW

PULITZER CENTER

Country:

PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES

PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES

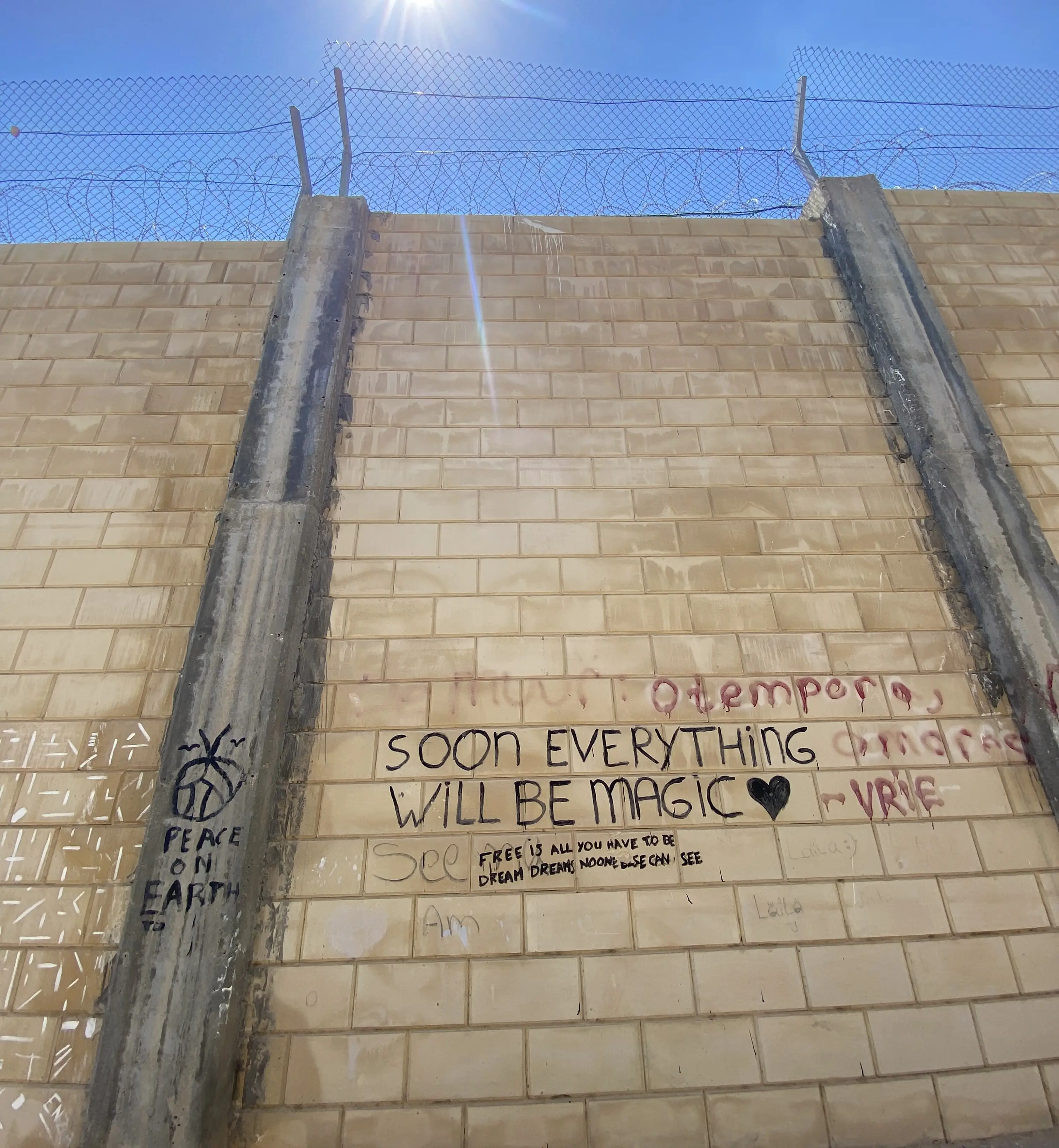

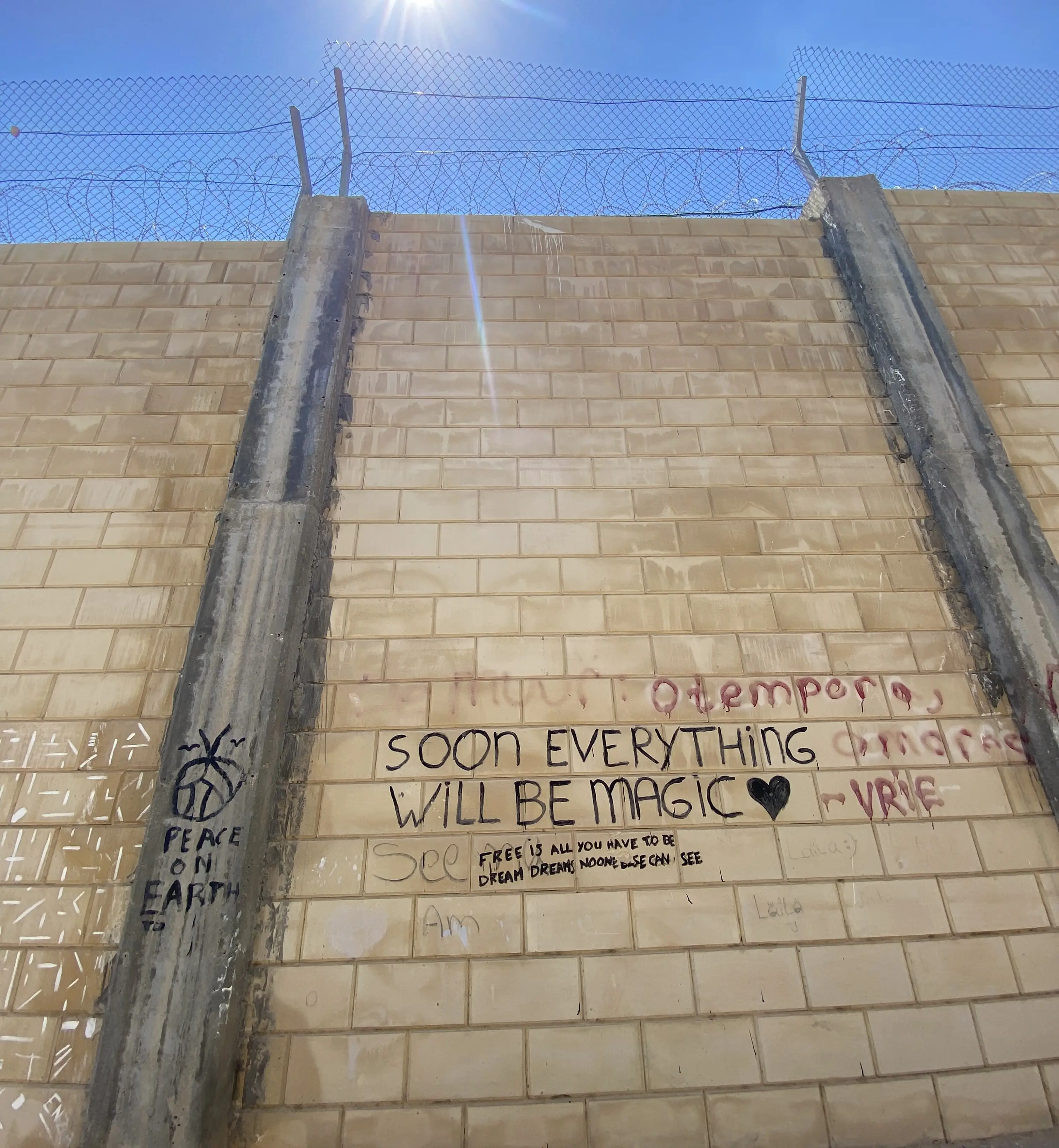

A section of the apartheid wall in Bethlehem, a five minute walk from Mariam's home.

Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

Mariam* is rebellious, she always has been.

You can often find her with a guitar in her lap, strumming chords to songs she wrote herself. Mari - am doesn’t know how to read music, no, she taught herself by listening, feeling the rhythm, matching her hand placement to the pitch of her voice. When Mariam sings, you feel, you understand, even if you don’t know the language of her Arabic words. She tilts her head back and shakes the red curls that pop against her pale face, curls as fiery as her personality. Around her, whether it be one or 20, people clap, smile, and sing along.

Fourteen years ago, Mariam and her husband founded a kindergarten and elementary school with the mission of providing holistic, trauma-in - formed education to children in the Palestinian town of Al-Eizariya and its surrounding areas. It is the first and only school of its kind in the West Bank to use non-violent and trauma-informed Waldorf education.

In Palestine, childhood is under attack. As of October 17, 2,226 children have been killed as a result of Israeli military and settler presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territories since 2000, according to Defence for Children International-Palestine (DCI).

The sun setting in the Jordan Desert. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

The cliff overlooks the Dead Sea, its blue water punctuated by pink mountains in the distance. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

“Each year approximately 500-700 Palestinian children, some as young as 12 years old, are detained and prosecuted in the Israeli military court system,” DCI stated. “The most common charge is stone throwing.”

It is this reality that makes Mariam’s work invaluable. Despite the obstacles of occupation, she has dedicated her life to bettering children’s lives through progressive, unconventional education.

Mariam describes herself as “different”—she recognizes that she doesn’t fit in' in Al-Eizariya. She knows to dress conservatively. Mariam wears long sleeve button-ups, loose t-shirts and pants that come down well past her knees, but she also has four tattoos. Only one is visible on a daily basis: the “om” on her forearm—a nod to the spirituality that guides her life and work. While Mariam was raised by a Catholic family in Bethlehem, the Church does not speak to her beliefs. Mariam is not religious. Instead, she believes in the power of the mind, body, and soul.

In any conversation, Mariam has a book to recommend, among them Paulo Cohelo’s The Alchemist and Rudolf Steiner’s Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment. A bowl of rubber bullets and empty tear gas canisters sit atop the bookshelf, the Hebrew letters fading from their silver shells. Mariam and her husband Khalil* collect them from their garden where Israeli soldiers throw them over the apartheid wall.

“This is just an appetizer,” Mariam explained about the small bowl. “I have garbage bags filled.”

Paintings of influential Palestinian leaders cover the wall of The Citadel, a cafe and community center in Beit Sahour, Bethlehem. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

Mariam grew up in a two-bedroom apartment tucked in between one of Bethlehem’s main streets, Al-Khalil Road, and the Al-Aza refugee camp. She lived with her two sisters and parents. As a child, Mariam remembers encountering soldiers and learning Hebrew through the cartoons on TV, but she didn’t immediately register this as Israeli occupation. She remembers the Second Intifada (2000-2005) as a defining period of her teenage years. Walking up the stairs to her childhood home, Mariam touched the remnants of bullet holes in the wall, now filled in with plaster. She explained that their building was often in the crossfire of clashes and violence. Inside the apartment, she folded her arms across her chest and squeezed herself into the corner between the kitchen and the living room, demonstrating her hiding position from the bullets that flew into her home. Once, when she returned from hiding at her grandparents’ home in the Old City, she found a bullet hole where her head would have been.

“Here,” Mariam pointed between her eyebrows, “it would have hit me right here.”

Next door, in the bedroom she shared with her sisters, Mariam showed me where she once hung a poster of Che Guevara.

“I started being different in all the ways,” Mariam explained about her adolescence. “I didn’t understand myself. I didn’t understand the community. I felt my energy is big and the community is small.”

Mariam was traumatized by the Intifada— the curfews, the lockdowns, the tear gas, the bombs, the tanks, the murders. She witnessed it all.

“Teenage years are hard enough without occupation.”

Palestinian flags line a stone archway in the village of Deir Istiya. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

"Soon everything will be magic," reads the graffiti on Al-Eizariya's apartheid wall, and underneath it, "Free is all you have to be, dream dreams no one else can see." Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

In early July, Mariam, her husband, and two children—eight-and 11-years-old—took me on a day trip to a Bedouin village in the Jordan Desert. A Bedouin tour guide drove us down a bumpy, rollercoaster-like path to a cli $ that overlooked the Dead Sea to watch the sunset. the view was breathtaking. The sea mirrored the blue sky, separated by pink mountains in the distance. It was a breath of fresh air from life under occupation: a reminder of the land’s beauty, tranquility, and ethereality that transcends con %ict. We all sat on the edge, mesmerized. Mariam walked o $ to a spot of her own, creating space for a moment of spirituality and connection.

I didn’t even realize when the Jeep pulled up.

Suddenly, four armed soldiers in camouflage suits and face masks stepped out of the vehicle. They started yelling in Arabic, Hebrew, and English for the family’s IDs. Apparently, we weren’t allowed to be there. Nowhere did I see a sign confirming their claims. I stood there frozen, watching a scene unfold that I had absolutely no control over. I wanted to scream, I wanted to tell them that we had every right to be here, that their humiliation tactics were so obviously a power trip—not law enforcement. I watched Mariam’s children hide in the back of the Jeep as their parents argued against a 300 US dollar fine for the driver.

“No, I don’t want to give you my ID,” she said. “No, I don’t want to give you my phone!”

Mariam had no fear, no hesitation.

Standing feet away from their M-16s, Mariam looked one of the soldiers in the eyes, the only part of his face visible.

“I know you are a human being. I know that you have a heart. But I see you killing me in the West Bank. This is what I have seen in my life.”

“Don’t continue! Khalas!” He yelled.

“You want me to stop because you don’t want to think,” Mariam continued. “You don’t want to feel your heart. You just want to say they are Arabs, they are enemies.”

Another soldier stepped in. “If you have a problem with occupation, go to the government,” he screamed. “Occupation is not my problem!”

They issued the fine, and before we left, ordered us to get out of the car. They searched every inch while we stood and watched.

Mariam turned to me. “They want to humiliate us.”

You can often find her with a guitar in her lap, strumming chords to songs she wrote herself. Mari - am doesn’t know how to read music, no, she taught herself by listening, feeling the rhythm, matching her hand placement to the pitch of her voice. When Mariam sings, you feel, you understand, even if you don’t know the language of her Arabic words. She tilts her head back and shakes the red curls that pop against her pale face, curls as fiery as her personality. Around her, whether it be one or 20, people clap, smile, and sing along.

Fourteen years ago, Mariam and her husband founded a kindergarten and elementary school with the mission of providing holistic, trauma-in - formed education to children in the Palestinian town of Al-Eizariya and its surrounding areas. It is the first and only school of its kind in the West Bank to use non-violent and trauma-informed Waldorf education.

In Palestine, childhood is under attack. As of October 17, 2,226 children have been killed as a result of Israeli military and settler presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territories since 2000, according to Defence for Children International-Palestine (DCI).

The sun setting in the Jordan Desert. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

The cliff overlooks the Dead Sea, its blue water punctuated by pink mountains in the distance. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

“Each year approximately 500-700 Palestinian children, some as young as 12 years old, are detained and prosecuted in the Israeli military court system,” DCI stated. “The most common charge is stone throwing.”

It is this reality that makes Mariam’s work invaluable. Despite the obstacles of occupation, she has dedicated her life to bettering children’s lives through progressive, unconventional education.

Mariam describes herself as “different”—she recognizes that she doesn’t fit in' in Al-Eizariya. She knows to dress conservatively. Mariam wears long sleeve button-ups, loose t-shirts and pants that come down well past her knees, but she also has four tattoos. Only one is visible on a daily basis: the “om” on her forearm—a nod to the spirituality that guides her life and work. While Mariam was raised by a Catholic family in Bethlehem, the Church does not speak to her beliefs. Mariam is not religious. Instead, she believes in the power of the mind, body, and soul.

In any conversation, Mariam has a book to recommend, among them Paulo Cohelo’s The Alchemist and Rudolf Steiner’s Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment. A bowl of rubber bullets and empty tear gas canisters sit atop the bookshelf, the Hebrew letters fading from their silver shells. Mariam and her husband Khalil* collect them from their garden where Israeli soldiers throw them over the apartheid wall.

“This is just an appetizer,” Mariam explained about the small bowl. “I have garbage bags filled.”

Paintings of influential Palestinian leaders cover the wall of The Citadel, a cafe and community center in Beit Sahour, Bethlehem. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

Mariam grew up in a two-bedroom apartment tucked in between one of Bethlehem’s main streets, Al-Khalil Road, and the Al-Aza refugee camp. She lived with her two sisters and parents. As a child, Mariam remembers encountering soldiers and learning Hebrew through the cartoons on TV, but she didn’t immediately register this as Israeli occupation. She remembers the Second Intifada (2000-2005) as a defining period of her teenage years. Walking up the stairs to her childhood home, Mariam touched the remnants of bullet holes in the wall, now filled in with plaster. She explained that their building was often in the crossfire of clashes and violence. Inside the apartment, she folded her arms across her chest and squeezed herself into the corner between the kitchen and the living room, demonstrating her hiding position from the bullets that flew into her home. Once, when she returned from hiding at her grandparents’ home in the Old City, she found a bullet hole where her head would have been.

“Here,” Mariam pointed between her eyebrows, “it would have hit me right here.”

Next door, in the bedroom she shared with her sisters, Mariam showed me where she once hung a poster of Che Guevara.

“I started being different in all the ways,” Mariam explained about her adolescence. “I didn’t understand myself. I didn’t understand the community. I felt my energy is big and the community is small.”

Mariam was traumatized by the Intifada— the curfews, the lockdowns, the tear gas, the bombs, the tanks, the murders. She witnessed it all.

“Teenage years are hard enough without occupation.”

Palestinian flags line a stone archway in the village of Deir Istiya. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

"Soon everything will be magic," reads the graffiti on Al-Eizariya's apartheid wall, and underneath it, "Free is all you have to be, dream dreams no one else can see." Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

In early July, Mariam, her husband, and two children—eight-and 11-years-old—took me on a day trip to a Bedouin village in the Jordan Desert. A Bedouin tour guide drove us down a bumpy, rollercoaster-like path to a cli $ that overlooked the Dead Sea to watch the sunset. the view was breathtaking. The sea mirrored the blue sky, separated by pink mountains in the distance. It was a breath of fresh air from life under occupation: a reminder of the land’s beauty, tranquility, and ethereality that transcends con %ict. We all sat on the edge, mesmerized. Mariam walked o $ to a spot of her own, creating space for a moment of spirituality and connection.

I didn’t even realize when the Jeep pulled up.

Suddenly, four armed soldiers in camouflage suits and face masks stepped out of the vehicle. They started yelling in Arabic, Hebrew, and English for the family’s IDs. Apparently, we weren’t allowed to be there. Nowhere did I see a sign confirming their claims. I stood there frozen, watching a scene unfold that I had absolutely no control over. I wanted to scream, I wanted to tell them that we had every right to be here, that their humiliation tactics were so obviously a power trip—not law enforcement. I watched Mariam’s children hide in the back of the Jeep as their parents argued against a 300 US dollar fine for the driver.

“No, I don’t want to give you my ID,” she said. “No, I don’t want to give you my phone!”

Mariam had no fear, no hesitation.

Standing feet away from their M-16s, Mariam looked one of the soldiers in the eyes, the only part of his face visible.

“I know you are a human being. I know that you have a heart. But I see you killing me in the West Bank. This is what I have seen in my life.”

“Don’t continue! Khalas!” He yelled.

“You want me to stop because you don’t want to think,” Mariam continued. “You don’t want to feel your heart. You just want to say they are Arabs, they are enemies.”

Another soldier stepped in. “If you have a problem with occupation, go to the government,” he screamed. “Occupation is not my problem!”

They issued the fine, and before we left, ordered us to get out of the car. They searched every inch while we stood and watched.

Mariam turned to me. “They want to humiliate us.”

This large red sign in Arabic, Hebrew, and English is common across the West Bank, often standing in the middle of a rotary that leads to a Palestinian city in one direction, and an Israeli settlement in the other. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

At the top of an apartment building overlooking Hebron, a satellite dish matches the view—homes surrounded by a wall on one side, and a fence on the other. Image by Laila Shadid. Palestinian Territories, 2022.

Later she explained how she felt, how the sight of these soldiers triggered her years of trauma.

“When I saw the soldiers, my mind blew away,” Mariam said. “How come you are here after me in the middle of the desert? I was unconscious and conscious at the same time.”

“Why is the occupation not ending?” she asked. “Because the government has brain - washed Israelis to believe they have to see us as enemies.”

“I am a nonviolent person. I really want peace, I want us to live all together. But I want my respect, I want my dignity, and I want my freedom.”

*All names have been changed.

RELATED CONTENT

The Story of Al-Eizariya: Jerusalem's Town Forgotten Behind the Wall

Laila Shadid

2022 REPORTING FELLOW

Project

Childhood Under Israeli Occupation: Stories From Palestine

Childhood Under Israeli Occupation: Stories From Palestine

No comments:

Post a Comment